Our Legacy of Religious Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles of the Church of Christ” in Relation to Section 20 of the Doctrine and Covenants

An Examination of the 829 “Articles of the Church of Christ” in Relation to Section 20 of the Doctrine and Covenants Scott H. Faulring he 829 “Articles of the Church of Christ” is a little-known anteced- Tent to section 20 of the Doctrine and Covenants. This article explores Joseph Smith’s and Oliver Cowdery’s involvement in bringing forth these two documents that were important in laying the foundation for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Section 20 was originally labeled the “Articles and Covenants.” It was the first revelation canonized by the restored Church and the most lengthy revelation given before the first priesthood conference was held in June 830. Scriptural commentators in recent years have described the inspired set of instructions in section 20 as “a constitution for the restored church.”1 In many respects, the Articles and Covenants was the Church’s earliest General Handbook of Instructions. Although Latter-day Saints typically associate the Articles and Covenants with the organization of the Church on April 6, 830, this regulatory document had roots in earlier events: in the earliest latter-day revelations, in statements on Church ordinances and organization from the Book of Mormon, and in the preliminary set of Articles written by Oliver Cowdery in the last half of 829. This article will review those early revelations to show how the organi- zation of the Church was prophetically foreshadowed and instituted. It will then identify certain prescriptions in the Book of Mormon that influenced the steps taken and pronouncements issued as the Church was organized on April 6, 830. -

University of Utah History 4795 Mormonism and the American Experience Fall Semester 2017 T, Th 2:00 – 3:20, WBB 617

University of Utah History 4795 Mormonism and the American Experience Fall Semester 2017 T, Th 2:00 – 3:20, WBB 617 W. Paul Reeve CTIHB 323 585-9231 Office hours: T, 10:30 – 11:30 a.m.; W, 2:00 p.m. – 3:00 p.m. [email protected] Course Description: This course explores the historical development of Mormonism in an American context, from its Second Great Awakening beginnings to the beginning of the twenty-first century. It situates the founding and development of Mormonism within the contexts of American cultural, economic, social, religious, racial, and political history. A central theme is the ebb and flow over time of tension between Mormonism and broader American society. How did conflicts over Mormonism during the nineteenth century, especially the conflict over polygamy and theocracy, help define the limits of religious tolerance in this country? How have LDS beliefs, practices, and culture positioned and repositioned Mormons within U.S. society? Learning Outcomes: 1. To situate the development of Mormonism within broader American historical contexts and thereby arrive at a greater understanding of religion’s place in American life. a. To understand the impact of Mormonism upon American history. b. To understand the impact of American history upon Mormonism. 2. To formulate and articulate in class discussions, exams, and through written assignments intelligent and informed arguments concerning the major developments and events that have shaped Mormonism over time. 3. To cultivate the critical mind in response to a variety of historical perspectives. Perspective: This course studies Mormonism in an academic setting. In doing so our purpose is not to debate the truth or falsehood of religious claims, but rather to examine how religious beliefs and experiences functioned in the lives of individuals and communities. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986

Journal of Mormon History Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 1 1986 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1986) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Table of Contents • --Mormon Women, Other Women: Paradoxes and Challenges Anne Firor Scott, 3 • --Strangers in a Strange Land: Heber J. Grant and the Opening of the Japanese Mission Ronald W. Walker, 21 • --Lamanism, Lymanism, and Cornfields Richard E. Bennett, 45 • --Mormon Missionary Wives in Nineteenth Century Polynesia Carol Cornwall Madsen, 61 • --The Federal Bench and Priesthood Authority: The Rise and Fall of John Fitch Kinney's Early Relationship with the Mormons Michael W. Homer, 89 • --The 1903 Dedication of Russia for Missionary Work Kahlile Mehr, 111 • --Between Two Cultures: The Mormon Settlement of Star Valley, Wyoming Dean L.May, 125 Keywords 1986-1987 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff LEONARD J. ARRINGTON, Editor LOWELL M. DURHAM, Jr., Assistant Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Assistant Editor FRANK McENTIRE, Assistant Editor MARTHA ELIZABETH BRADLEY, Assistant Editor JILL MULVAY DERR, Assistant Editor Board of Editors MARIO DE PILLIS (1988), University of Massachusetts PAUL M. -

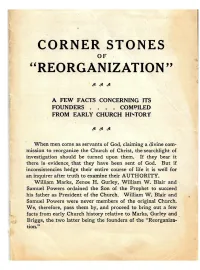

Corner Stones of Reorganization

CORNER STONES OF "REORGANIZATION" A A A A FEW FACTS CONCERNING ITS FOUNDERS . COMPILED FROM EARLY CHURCH HP,TOR Y A A A When men come as servants of God, claiming a divine com- mission to reorganize the Church of Christ, the searchlight of investigation should be turned upon them. If they bear it there is evidence, that they have been sent of God. But if inconsistencies hedge their entire course of life it is well for an inquirer after truth to examine their AUTHORITY. William Marks, Zenos H. Gurley, William W. Blair and Samuel Powers ordained the Son of the Prophet to succeed his father as President of the Church. William W. Blair and Samuel Powers were never members of the original Church. We, therefore, pass them by, and proceed to bring out a few facts from early Church history relative to Marks, Gurley and Briggs, the two latter being the founders of the "Reorganiza- tion." HISTORY OF WILLIAM MARKS. After making this acknowledgment he was received back WILLIAM MARKS was President of the Nauvoo Stake at into fellowship, but did not again obtain his former position. the time of the martyrdom of the Prophet Joseph, June 27, He became dissatisfied, withdrew from the Church and was 1844. excommunicated. SOMETHING FROM THE PROPHET'S JOURNAL. JOINS THE STRANGITE ORGANIZATION AND PLAYS A LEADING PART. "Whatever can be the matter with these men (Law and Marks) ? Is it that the wicked flee when no man pursueth? Copied from the "Voree Record," official record of that hit pigeons always flutter? that drowning men catch at Strangite Church. -

The Book of Mormon Witnesses and Their Challenge to Secularism

INTERPRETER§ A Journal of Mormon Scripture Volume 27 · 2017 · Pages vii-xxviii The Book of Mormon Witnesses and Their Challenge to Secularism Daniel C. Peterson Offprint Series © 2017 The Interpreter Foundation. A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. ISSN 2372-1227 (print) ISSN 2372-126X (online) The goal of The Interpreter Foundation is to increase understanding of scripture through careful scholarly investigation and analysis of the insights provided by a wide range of ancillary disciplines, including language, history, archaeology, literature, culture, ethnohistory, art, geography, law, politics, philosophy, etc. Interpreter will also publish articles advocating the authenticity and historicity of LDS scripture and the Restoration, along with scholarly responses to critics of the LDS faith. We hope to illuminate, by study and faith, the eternal spiritual message of the scriptures—that Jesus is the Christ. Although the Board fully supports the goals and teachings of the Church, The Interpreter Foundation is an independent entity and is neither owned, controlled by nor affiliated with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or with Brigham Young University. All research and opinions provided are the sole responsibility of their respective authors, and should not be interpreted as the opinions of the Board, nor as official statements of LDS doctrine, belief or practice. This journal is a weekly publication. -

Doctrine and Covenants 135 John Taylor's Martyrdom Document, June, 1844

1 DOCTRINE & COVENANTS 131-132 CHRONOLOGY September 28, 1843 – Emma Smith temporarily accepts polygamy. The temple quorum receives Emma as the first woman of the quorum and the highest ordinances of the gospel are for the first time delivered to JS and Emma together. JS voted President of the temple quorum. October 8, 1843 – JS moves to remove Sidney Rigdon from the FP, however the General Conference, refuses to allow it. November 29, 1843 – JS preaches against State's rights. December 23, 1843 – Emma Smith's last meeting with the Temple quorum. January 7, 1844 – Temple Quorum votes to expel William Law, second counselor in the FP. January 29, 1844 – Quorum of the Twelve nominate JS as an independent candidate for the US Presidency. February 21, 1844 – JS instructs the Q12 to select men to explore the West outside of the US for potential new headquarters. February 25, 1844 – Temple quorum approves distribution of JS's Presidential Platform (including provision to free the slaves). March 11, 1844 – Council of Fifty organized. March 23, 1844 – JS delivers "Last Charge" to the Q12 at a meeting of the Council of Fifty. April 7, 1844 – JS delivers Famous King Follett Sermon at General Conference. April 8, 1844 – JS delivers sermon, shift in gathering. April 11, 1844 – JS anointed King, Priest and Ruler by the Council of Fifty. April 18, 1844 – William Law excommunicated. May 12, 1844 – William Law's new Reformed Church attracts hundreds as he preaches against polygamy and theocracy. May 21, 1844 – Apostles and many other Church leaders leave Nauvoo t campaign for JS's bid for US President. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988

Journal of Mormon History Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 1 1988 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1988) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol14/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988 Table of Contents • --The Popular History of Early Victorian Britain: A Mormon Contribution John F. C. Harrison, 3 • --Heber J. Grant's European Mission, 1903-1906 Ronald W. Walker, 17 • --The Office of Presiding Patriarch: The Primacy Problem E. Gary Smith, 35 • --In Praise of Babylon: Church Leadership at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London T. Edgar Lyon Jr., 49 • --The Ecclesiastical Position of Women in Two Mormon Trajectories Ian G Barber, 63 • --Franklin D. Richards and the British Mission Richard W. Sadler, 81 • --Synoptic Minutes of a Quarterly Conference of the Twelve Apostles: The Clawson and Lund Diaries of July 9-11, 1901 Stan Larson, 97 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol14/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History , VOLUME 14, 1988 Editorial Staff LOWELL M. DURHAM JR., Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Associate Editor MARTHA SONNTAG BRADLEY, Associate Editor KENT WARE, Designer LEONARD J. -

Tangible Restoration: the Witnesses and What They Experienced

Tangible Restoration: The Witnesses and What They Experienced By Daniel C. Peterson 2006 FAIR Conference Joseph Smith’s claims regarding the Book of Mormon seem, at least on the surface, to be very detailed and utterly tangible. They are not mystical claims, but, at least in principle, can be tested in the real world of everyday, physical objects. And critics have not been reluctant to meet the claim head on. “As for the golden plates,” wrote the evangelical Protestant polemicist G.H. Fraser, “we will say simply that there were not any.” But the historical evidence suggests—no, it shouts—the contrary. A representative statement is that given by David Whitmer during an 1878 interview with Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith: It was in June, 1829, the latter part of the month . Martin Harris was not with us at this time; he obtained a view of [the plates] afterwards (the same day). Joseph, Oliver, and myself were together when I saw them. We not only saw the plates of the Book of Mormon, but also the brass plates [a set of records mentioned early in the Book of Mormon has having been carried by Lehi from Jerusalem to the New World], the plates of the book of Ether, the plates containing the record of the wickedness and secret combinations of the people of the world down to the time of their being engraved, and many other plates. The fact is, it was just as though Joseph, Oliver and I were sitting just here on a log, when we were overshadowed by a light. -

A Period of Trials and Testing

35448 HeritageBODY 01-12-2005 2:50 PM Page 92 Thousands of Saints gathered to witness the laying of the capstone on the Salt Lake Temple, 6 April 1892. 92 35448 HeritageBODY 01-12-2005 2:50 PM Page 93 CHAPTER EIGHT A Period of Trials and Testing President John Taylor After President Brigham Young died, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, presided over by John Taylor, led the Latter-day Saints for three years. On 10 October 1880, John Taylor was sustained as President of the Church. President Taylor was a gifted writer and journalist who published a book on the Atonement and edited some of the Church’s most important periodicals, including the Times and Seasons and the Mormon. On many occasions he displayed his courage and his deep devotion to the restored gospel, including voluntarily joining his brethren in Carthage Jail, where he was shot four times. His personal motto, “The kingdom of God or nothing,” signified his loyalty to God and the Church. Missionary Work President Taylor was committed to doing all he could to see that the gospel was proclaimed to the ends of the earth. In the October 1879 general conference, he called Moses Thatcher, the Church’s newest Apostle, to begin proselyting in Mexico City, Mexico. Elder Thatcher and two other missionaries organized the first branch of the Church in Mexico City on 13 November 1879, with Dr. Plotino C. Rhodacanaty as the branch president. Dr. Rhodacanaty had been converted after reading a Spanish Book of Mormon pamphlet and writing to President Taylor for additional information about the Church. -

Identity Maintenance in the 1844 Latter-Day Saint Reform Sect Robert M

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2017 Anatomy of a Rupture: Identity Maintenance in the 1844 Latter-day Saint Reform Sect Robert M. Call Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Call, Robert M., "Anatomy of a Rupture: Identity Maintenance in the 1844 Latter-day Saint Reform Sect" (2017). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 5858. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/5858 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANATOMY OF A RUPTURE: IDENTITY MAINTENANCE IN THE 1844 LATTER-DAY SAINT REFORM SECT by Robert M. Call A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in History Approved: _________________________ _________________________ Philip Barlow, Ph.D. Kyle T. Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member _________________________ _________________________ Clint Pumphrey Mark McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2017 ii Copyright © Robert M. Call 2017 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Anatomy of a Rupture: Identity Maintenance in the 1844 Latter-day Saint Reform Sect by Robert M. Call, Master of Science Utah State University, 2017 Major Professor: Philip Barlow Department: History Dissent riddled Mormonism almost from the day of its inception. -

The Politics of Schism. the Origins of Dissent in Mormonism

Studia Religiologica 49 (3) 2016, s. 203–218 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.16.014.5872 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica The Politics of Schism. The Origins of Dissent in Mormonism Maciej Potz Faculty of International and Political Studies University of Lodz Abstract Throughout nearly two ages of its history, and especially in the 19th century, Mormonism has expe- rienced numerous cases of dissent and schism. Analysis of their sources reveals that, among a num- ber of doctrinal, ritual, organisational and other issues, the single most important cause of schism was conflicts over authority. These power struggles are explained – within a theoretical framework derived from the theory of social exchange – as balancing operations intended to improve the ac- tors’ position in unequal exchange relations: to be able to obtain the valuable religious goods at a lower price (i.e. less or no submission). Key words: Mormonism, schism, political power, theory of social exchange Słowa kluczowe: mormonizm, schizma, władza polityczna, teoria wymiany społecznej Although Mormonism has been mainly associated, both in scholarly literature and among the general public, with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) – by far its largest and fastest growing organisation – it is, in fact, a broader religious phenomenon which has given rise to more than a hundred religious groups of various sizes and lifespans, all subscribing to the legacy (or parts thereof) of Joseph Smith, the religion’s founding prophet. The circumstances in which these groups emerged and the reasons why they chose to dissociate from the main body of the Church var- ied, and no uniform explanation of all these schisms is therefore possible. -

Martin Harris and the Strangite Mission

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 44 Issue 3 Article 5 9-1-2005 A Witness in England: Martin Harris and the Strangite Mission Robin Scott Jensen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Jensen, Robin Scott (2005) "A Witness in England: Martin Harris and the Strangite Mission," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 44 : Iss. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol44/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Jensen: A Witness in England: Martin Harris and the Strangite Mission Courtesy Church Archives © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Fig. 1. Martin Harris (1783–1875). Harris was one of the Three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon. Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2005 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 44, Iss. 3 [2005], Art. 5 A Witness in England Martin Harris and the Strangite Mission Robin Scott Jensen hroughout his long life, Martin Harris (fig. 1) consistently testified Tthat he knew Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon from golden plates. At first affiliated with Joseph Smith and the main body of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, for a time Harris associated with a schism led by James J. Strang. He served a mission in England in 1846 for the Strangites,1 but he claimed to the end of his life that he had never preached against Mormonism or against the Book of Mormon.2 Indeed, he was a powerful witness of the Book of Mormon during his mission.