Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the HIGH COURT of JUDICATURE at BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION NO. 3370 of 2018 Shri Anandra Vitho

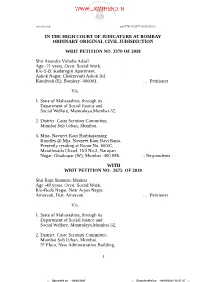

spb/vai/ppn/bdp wp3370-18-2675-9426-20.doc IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION NO. 3370 OF 2018 Shri Anandra Vithoba Adsul Age -71 years, Occu: Social Work, R/o-5-B, Kadamgiri Apartment, Ashok Nagar, Chakravarti Ashok Rd, Kandivali (E), Bombay- 400001. … Petitioner V/s. 1. State of Maharashtra, through its Department of Social Justice and Social Welfare, Mantralaya,Mumbai-32. 2. District Caste Scrutiny Committee, Mumbai Sub Urban, Mumbai. 3. Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Presently residing at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086. ... Respondents WITH WRIT PETITION NO. 2675 OF 2019 Shri Raju Shamrao Mankar Age -49 years, Occu: Social Work, R/o-Boda Nagar, Near Arjun Nagar, Amravati, Dist. Amravati. … Petitioner V/s. 1. State of Maharashtra, through its Department of Social Justice and Social Welfare, Mantralaya,Mumbai-32. 2. District Caste Scrutiny Committee, Mumbai Sub Urban, Mumbai. th 5 Floor, New Administrative Building, 1 ::: Uploaded on - 08/06/2021 ::: Downloaded on - 08/06/2021 13:37:37 ::: spb/vai/ppn/bdp wp3370-18-2675-9426-20.doc Bandra, Mumbai. 3. Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Presently residing at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086. ... Respondents --- WITH WRIT PETITION (LDG.) NO. 9426 OF 2020 Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Age-35 years, Occu. Social Work. R/at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086 At present residing at - Ganga Savitri Banglow, Plot No. -

Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯

religions Article Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯ Peter Friedlander South and South East Asian Studies Program, School of Culture History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2600, Australia; [email protected] Received: 13 March 2020; Accepted: 23 April 2020; Published: 1 May 2020 Abstract: Jagjivan Ram (1908–1986) was, for more than four decades, the leading figure from India’s Dalit communities in the Indian National Congress party. In this paper, I argue that the relationship between religion and politics in Jagjivan Ram’s career needs to be reassessed. This is because the common perception of him as a secular politician has overlooked the role that his religious beliefs played in forming his political views. Instead, I argue that his faith in a Dalit Hindu poet-saint called Ravidas¯ was fundamental to his political career. Acknowledging the role that religion played in Jagjivan Ram’s life also allows us to situate discussions of his life in the context of contemporary debates about religion and politics. Jeffrey Haynes has suggested that these often now focus on whether religion is a cause of conflict or a path to the peaceful resolution of conflict. In this paper, I examine Jagjivan Ram’s political life and his belief in the Ravidas¯ ¯ı religious tradition. Through this, I argue that Jagjivan Ram’s career shows how political and religious beliefs led to him favoring a non-confrontational approach to conflict resolution in order to promote Dalit rights. Keywords: religion; politics; India; Congress Party; Jagjivan Ram; Ravidas;¯ Ambedkar; Dalit studies; untouchable; temple building 1. -

Buddhism, Democracy and Dr. Ambedkar: the Building of Indian National Identity Milind Kantilal Solanki, Pratap B

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-4, Issue-4, Jul – Aug 2019 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.4448 ISSN: 2456-7620 Buddhism, Democracy and Dr. Ambedkar: The Building of Indian National Identity Milind Kantilal Solanki, Pratap B. Ratad Assistant Professor, Department of English, KSKV Kachchh University, Bhuj, Gujrat, India Research Scholar, Department of English, KSKV Kachchh University, Bhuj, Gujrat, India Abstract— Today, people feel that democratic values are in danger and so is the nation under threat. Across nations we find different systems of government which fundamentally take care of what lies in their geographical boundaries and the human lives living within it. The question is not about what the common-man feels and how they survive, but it is about their liberty and representation. There are various forms of government such as Monarchy, Republic, Unitary State, Tribalism, Feudalism, Communism, Totalitarianism, Theocracy, Presidential, Socialism, Plutocracy, Oligarchy, Dictatorship, Meritocracy, Federal Republic, Republican Democracy, Despotism, Aristocracy and Democracy. The history of India is about ten thousand years and India is one of the oldest civilizations. The democratic system establishes the fundamental rights of human beings. Democracy also takes care of their representation and their voice. The rise of Buddhism in India paved the way for human liberty and their suppression from monarchs and monarchy. The teachings of Buddha directly and indirectly strengthen the democratic values in Indian subcontinent. The rise of Dr. Ambedkar on the socio-political stage of this nation ignited the suppressed minds and gave a new hope to them for equality and equity. -

Ambedkar and the Dalit Buddhist Movement in India (1950- 2000)

International Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 2 Issue 6 ǁ July 2017. www.ijahss.com Ambedkar and The Dalit Buddhist Movement in India (1950- 2000) Dr. Shaji. A Faculty Member, Department of History School of Distance Education University of Kerala, Palayam, Thiruvananthapuram Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar was one of the most remarkable men of his time, and the story of his life is the story of his exceptional talent and outstanding force of character which helped him to succeed in overcoming some of the most formidable obstacles that an unjust and oppressive society has ever placed in the way of an individual. His contribution to the cause of Dalits has undoubtedly been the most significant event in 20th century India. Ambedkar was a man whose genius extended over diverse issues of human affairs. Born to Mahar parents, he would have been one of the many untouchables of his times, condemned to a life of suffering and misery, had he not doggedly overcome the oppressive circumstances of his birth to rise to pre-eminence in India‘s public life. The centre of life of Ambedkar was his devotion to the liberation of the backward classes and he struggled to find a satisfactory ideological expression for that liberation. He won the confidence of the- untouchables and became their supreme leader. To mobilise his followers he established organisations such as the Bahishkrit Hitkarni Sabha, Independent Labour Party and later All India Scheduled Caste Federation. He led a number of temple-entry Satyagrahas, organized the untouchables, established many educational institutions and propagated his views through newspapers like the 'Mooknayak', 'Bahishkrit Bharat' and 'Janata'. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Understanding the Contribution of Satya Shodhaak Samaj and Neo- Buddhism for Social Awakening

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347–4564; ISSN (E): 2321–8878 Vol. 8, Issue 6, Jun 2020, 53–60 © Impact Journals UNDERSTANDING THE CONTRIBUTION OF SATYA SHODHAAK SAMAJ AND NEO- BUDDHISM FOR SOCIAL AWAKENING Prashant V. Ransure & Pankajkumar Shankar Premsagar Assistant Professor, Department of History, Maratha Vidya Prasarak Samaj's Arts Science and Commerce College Ozar MIG, Maharashtra, India Associate Professor, Department of History, Smt. G. G. Khadse College, Muktainagar, India Received: 10 Jun 2020 Accepted: 16 Jun 2020 Published: 27 Jun 2020 ABSTRACT Indian Civilization is the conglomeration of various ethnic traditions; Years of amalgamation and change have led Indian civilization to have, diversity of culture religion, language, and caste groups. Indian Civilization is the conglomeration of various ethnic traditions; Years of amalgamation and change have led Indian civilization to have diversity of culture religion, language, and caste groups.1 The social reform movements, tried for the emancipation of these low caste people, before coming of these social reformers, many of the low caste people had chosen to come out from the caste system is by getting religious conversion, getting converted either to Christianity or to Islam, prior to these social reformers the saints like Kabir, Ravidas, Namdev, like wise and many other fought for the abolition of the caste system and emancipate the low caste from the social bondages.2 The other way for the untouchables was to get converted to either Islam or to Christianity, this was to get rid of the bondages of the humiliations of the caste system, but the conversion was not confined to the weaker sections, but in the medieval period too many people got converted to Islam or Christianity either by force or by their will. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

Navayana – a Reformation of Buddhism

Journal of Ethnophilosophical Questions and Global Ethics – Vol. 1 (1), 2017 Navayana – A reformation of Buddhism Timo Schmitz Buddhism traditionally has three variants: Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. The oldest one is Theravada, which is an orthodox tradition practiced in South Asia, later Mahayana developed as lay- follower tradition, mainly in East Asia. However, in times of globalization, Buddhism is confronted with new issues and also found its way to the West, as well as to political spheres. As George Boeree states: “Many of us, easterners and westerners, have been profoundly influenced by our study of Buddhism, and yet do not find ourselves attached to any one particular sect or interpretation of Buddhism. Further, many of us, especially westerners, find the fundamental ideas of Buddhism deeply meaningful, but cannot, without being dishonest with ourselves, accept certain other ideas usually associated with Buddhism” (Boeree, 2002). In recent years, new branches such as Secular Buddhism or Engaged Buddhism have found its way into philosophical and practical main streams. The need to reform Buddhism arouse out of the fact that Buddhism gained attraction for non-conformity and non-dogmatism, something which religion in the West seemingly could not give Westerners, just to find out that Buddhism has the same matters. As Timo Schmitz points out: “Many people want to find the way to Buddhism because they are against any doctrines. Therefore, one can study the Theravada teachings, which leads to a disadvantage in the eyes of many Westerners since it focusses on monk communities. Other people are fascinated by Vajrayana, but since it has a very organized structure, concerning hierarchy and practice, one will probably see the Vajrayana tradition to be a religiously-organized branch, which in the Western view can be seen as dogmatic again. -

Revivals of Ancient Religious Traditions in Modern India: Sāṃkhyayoga And

Revivals of ancient religious traditions in modern India: S khyayoga and Buddhism āṃ KNUT A. JACOBSEN University of Bergen Abstract The article compares the early stages of the revivals of S khyayoga and Buddhism in modern India. A similarity of S khyayoga and Buddhism was that both had disappeared from India andāṃ were re- vived in the modern period, partly based on Orientalistāṃ discoveries and writings and on the availability of printed books and publishers. Printed books provided knowledge of ancient traditions and made re-establishment possible and printed books provided a vehicle for promoting the new teachings. The article argues that absence of com- munities in India identified with these traditions at the time meant that these traditions were available as identities to be claimed. Keywords: Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Hariharānanda Āraṇya, Navayana Buddhism, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries both S khyayoga and Indian Buddhism were revived in India. In this paper I compare and contrast these revivals, and suggest why they happened. S khyayogaāṃ and Buddhism had mainly disappeared as living traditions from the central parts of India before the modern period and their absence openedāṃ them to the claims of various groups. The only living S khyayoga monastic tradition in India based on the Pātañjalayogaśāstra, the K pil Ma h tradition founded by Harihar nanda ya (1869–1947), wasāṃ a late nineteenth-century re-establishment (Jacob- sen 2018). There were no monasticā ṭ institutions of S khyayoga saṃānyāsins basedĀraṇ on the Pātañjalayogaśāstra in India in 1892, when ya became a saṃnyāsin, and his encounter with the teachingāṃ of S mkhyayoga was primarily through a textual tradition (Jacobsen 2018). -

Ambedkar's Vision

Ambedkar’s Vision The Buddhist revival in India ignited by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar more than fifty years ago has brought millions of the country’s most impoverished and marginalized people to the Buddhist path. There is much we can learn from them, says Alan Senauke. buddhadharma: the practitioner’s quarterly SPRING 2011 62 PHOTO PHIL CLEVENGER (Facing page) Dr. B.R. Ambedkar painted on a wall in Bangalore, India With justice on our side, I do not see how we can lose our HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT, a modern Buddhist revolution is battle. The battle to me is a matter of joy… For ours is a gaining ground in the homeland of Shakyamuni. It’s being led battle not for wealth or for power. It is a battle for freedom. by Indian Buddhists from the untouchable castes, the poorest It is a battle for the reclamation of the human personality. of the poor, who go by various names: neo-Buddhists, Dalit Buddhists, Navayanists, Ambedkarites. But like so much in — Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, their lives, these names carry a subtle odor of condescension All-India Depressed Classes Conference, 1942 that suggests their kind of Buddhism is something less than the real thing. In the children’s hostels and schools of Nagpur or modest viharas in Mumbai’s Bandra East slums and the impoverished Dapodi neighborhood in Pune, one finds people singing simple PHOTOS ALAN SENAUKE H63 SPRING 2011 buddhadharma: the practitioner’s quarterly When Ambedkar returned to India to practice law, he was one of the best-educated men in the country, but, as an untouchable, he was unable to find housing and prohibited from dining with his colleagues. -

District Census Handbook, North Goa

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 6 GOA DISTRICT CENSUS HAND BOOK PART XII-A AND XII-B VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY AND VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT NORTH GOA DISTRICT S. RAJENDRAN DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, GOA 1991 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS OF GOA ( All the Census Publications of this State will bear Series No.6) Central Government Publications Part Administration Report. Part I-A Administration Report-Enumeration. (For Official use only). Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation. Part II General Population Tables Part II-A General Population Tables-A- Series. Part II-B Primary Census Abstract. Part III General Economic Tables Part III-A B-Series tables '(B-1 to B-5, B-l0, B-II, B-13 to B -18 and B-20) Part III-B B-Series tables (B-2, B-3, B-6 to B-9, B-12 to B·24) Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part IV-A C-Series tables (Tables C-'l to C--6, C-8) Part IV -B C.-Series tables (Table C-7, C-9, C-lO) Part V Migration Tables Part V-A D-Series tables (Tables D-l to D-ll, D-13, D-15 to D- 17) Part V-B D- Series tables (D - 12, D - 14) Part VI Fertility Tables F-Series tables (F-l to F-18) Part VII Tables on Houses and Household Amenities H-Series tables (H-I to H-6) Part VIII Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled SC and ST series tables Tribes (SC-I to SC -14, ST -I to ST - 17) Part IX Town Directory, Survey report on towns and Vil Part IX-A Town Directory lages Part IX-B Survey Report on selected towns Part IX-C Survey Report on selected villages Part X Ethnographic notes and special studies on Sched uled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part XI Census Atlas Publications of the Government of Goa Part XII District Census Handbook- one volume for each Part XII-A Village and Town Directory district Part XII-B Village and Town-wise Primary Census Abstract GOA A ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS' 1991 ~. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798.