Mortimer and Balazs (2000) Post-Nesting Migrations of Hawksbill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Insights from a Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus Sechellensis) Translocation

Journal of Ornithology (2018) 159:439–446 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-017-1518-8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The importance of post‑translocation monitoring of habitat use and population growth: insights from a Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis) translocation Thomas F. Johnson1 · Thomas J. Brown2 · David S. Richardson2,3 · Hannah L. Dugdale1 Received: 20 July 2017 / Revised: 17 September 2017 / Accepted: 2 November 2017 / Published online: 23 November 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Translocations are a valuable tool within conservation, and when performed successfully can rescue species from extinction. However, to label a translocation a success, extensive post-translocation monitoring is required, ensuring the population is grow- ing at the expected rate. In 2011, a habitat assessment identifed Frégate Island as a suitable island to host a Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis) population. Later that year, 59 birds were translocated from Cousin Island to Frégate Island. Here, we determine Seychelles Warbler habitat use and population growth on Frégate Island, assessing the status of the translocation and identifying any interventions that may be required. We found that territory quality, an important predictor of fedgling production on Cousin Island, was a poor predictor of bird presence on Frégate Island. Instead, tree diversity, middle-storey vegetation density, and broad-leafed vegetation density all predicted bird presence positively. A habitat suitability map based on these results suggests most of Frégate Island contains either a suitable or a moderately suitable habitat, with patches of unsuitable overgrown coconut planta- tion. To achieve the maximum potential Seychelles Warbler population size on Frégate Island, we recommend habitat regeneration, such that the highly diverse subset of broad-leafed trees and a dense middle storey should be protected and replace the unsuitable coconut. -

Evolutionary and Conservation Genetics of the Seychelles Warbler ( Acrocephalus Sechellensis )

Evolutionary and conservation genetics of the Seychelles warbler ( Acrocephalus sechellensis ) David John Wright A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences University of East Anglia, UK May 2014 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. This thesis is dedicated to Laura, my wife and partner-in-crime, for the endless supply of love, support, tea and cake. ii Abstract In this thesis, I investigated how evolutionary forces and conservation action interact to shape neutral and adaptive genetic variation within and among populations. To accomplish this, I studied an island species, the Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis ), with microsatellite markers and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes as measures of neutral and adaptive variation respectively. First, I used museum DNA and historical records to reveal a recent bottleneck that provides context for the contemporary genetic variation observed in this species. I then determined the impact of four translocations on genetic diversity over two decades. I found that diversity does not differ significantly between islands but the use of smaller founder sizes in two translocations has caused population divergence. These results indicate that stochastic genetic capture is important in translocations and that future assisted gene flow between populations may be necessary. As a tool for conservation practitioners, I wrote a technical report of the most recent translocation - to Frégate Island - detailing practicalities and outcomes to help inform future translocation policy. -

Family Seychelles: Rain Forests and Reefs of the Indian Ocean March 17—29, 2017

Family Seychelles: Rain Forests and Reefs of the Indian Ocean March 17—29, 2017 In 1990, 2009, and 2013, Museum Curator Chris Raxworthy and research teams traveled to the Seychelles, where they scoured lush canyons, rocky shores, and steep cliff sides to survey amphibians and reptiles of the Indian Ocean. The information, observations, and genetic samples collected during these expeditions are helping scientists understand the evolutionary history of these organisms and have proven critical to the development of conservation strategies in the region. Embark on your own expedition custom-designed exclusively for Patrons Circle Members by Dr. Raxworthy to highlight the extraordinary biodiversity of the Seychelles’ verdant tropical rain forests and spectacular coral reefs. Activities created by Museum educator Jean Rosenfeld make learning a fun and exciting adventure for the entire family. HIGHLIGHTS EXPLORE the forests of Silhouette Island during the day and at night to search for native wildlife. WONDER at the iconic Coco de Mer, the world’s largest nut of 130-foot-tall palm trees, and hunt for a giant gecko that went missing to science for more than one hundred years. MEET conservation specialists who monitor bird populations on Aride Island, home to the most significant seabird population in the Indian Ocean. SPOT abundant endemic species on Cousin Island, a former coconut plantation that has been reclaimed as a diverse ecosystem, and get close to giant Indian Ocean tortoises. SNORKEL with rare marine life such as hawksbill and green turtles, octopuses, and a kaleidoscope of fish species found on the vibrant reefs of Mahé and Praslin Islands. -

Praslin, Seychelles

EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW TO ENJOY YOUR NEXT DREAM DESTINATION! INDIAN OCEAN| PRASLIN, SEYCHELLES PRASLIN BASE ADDRESS Praslin Baie Sainte Anne Praslin 361 GPS POSITION: 4°20.800S 55°45.909E OPENING HOURS: 8:30am – 5pm BASE MAP BASE CONTACTS If you need support while on your charter, contact the base immediately using the contact details in this guide. Please contact your booking agent for all requests prior to your charter. BASE MANAGER Base Manager: Pierre Piveteau Phone: +248 25 27 662 Email: [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE PRASLIN Customer Service Manager: Devina Bouchereau Phone: +248 26 44 701 Email: [email protected] BASE FACILITIES ☒ Electricity ☒ Luggage storage ☒ Water ☐ Restaurant ☒ Toilets ☐ Bar ☒ Showers ☒ Supermarket / Grocery store ☒ Laundry ☐ ATM ☐ Swimming pool ☐ Post Office ☐ Wi-Fi BASE INFORMATION LICENSE Sailing license required: ☒ Yes ☐ No PAYMENT The base can accept: ☒ Visa ☒ MasterCard ☐ Amex ☒ Cash EMBARKATION TIME Embarkation is 3pm. YACHT BRIEFING All briefings are conducted on the chartered yacht and will take 40-60 minutes, depending on yacht size and crew experience. The team will give a detailed walk-through of your yacht’s technical equipment, information about safe and accurate navigation, including the yacht’s navigational instruments, as well as mooring, anchorage and itinerary help. The safety briefing introduces the safety equipment and your yacht’s general inventory. STOP OVERS For all DYC charters starting and/or ending in Praslin, the first and last night at the marina is free of charge, including water, electricity and use of shower facilities. DISEMBARKATION TIME Disembarkation is at 9am. The team will inspect your yacht’s equipment and a general visual check of its interior and exterior. -

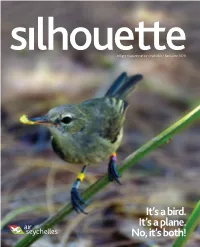

It's a Bird. It's a Plane. No, It's Both!

HM Silhouette Cover_Apr2019-Approved.pdf 1 08/03/2019 16:41 Inflight magazine of Air Seychelles • April-June 2020 It’s a bird. It’s a plane. No, it’s both! 9405 EIDC_Silhou_IBC 3/5/20 8:48 AM Page 5 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composite [ CEO’S WELCOME ] Dear Guests, Welcome aboard! As you are probably aware, the aviation industry globally is under considerable pressure over the issue of carbon emissions and its impact on climate change. At Air Seychelles we are indeed proud of the contribution we are making towards sustainable development. Following the successful delivery of our second Airbus A320neo aircraft, Pti Merl Dezil in March 2020, I am pleased to announce that Air Seychelles is now operating the youngest jet fleet in the Indian Ocean. Performing to standard, the new engine option aircraft is currently on average generating 20% fuel savings per flight and 50% reduced noise footprint. This amazing performance cannot go unnoticed and we remain committed to further implement ecological measures across our business. Apart from keeping Seychelles connected through air access, Air Seychelles also provides ground handling services to all customer airlines operating at the Seychelles International Airport. Following an upsurge in the number of carriers coming into the Seychelles, in 2019 we surpassed the 1 million passenger threshold handled at the airport, recording an overall growth of 5% increase in arrival and departures. Combining both inbound and outbound travel including the domestic network, Air Seychelles alone contributed a total of 414,088 passengers after having operated 1,983 flights. -

(Eretmochelys Imbricata) on Cousine Island, Seychelles, 1995-1999

Factors influencing emergences and nesting sites of hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) on Cousine Island, Seychelles, 1995-1999 P.M. Hitchins, O. Bourquin*, S. Hitchins &S.E. Piper** Cousine Island, P.O. Grand Anse, Praslin, SEYCHELLES * P.O. Box 10001, PMB 33, Saipan, MP 96950-8901, USA **Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg KwaZulu-Natal, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract: Nesting hawksbill turtles were studied on Cousine Island, Seychelles from 1995 – 1999. Emer- gences were highest during November and December, and most (91.0%) took place between October and January when the beaches were most stable and the general wind speeds were at a minimum, with 99.4% emergences occurring during daylight. There was no correlation between emergences and tidal conditions, lunar cycles, daily wind, rainfall, and eroding or depositing beaches. Most nesting took place on or beyond the upper third of beaches. There did not appear to be any special selection for sunlit or shaded conditions, or for vegetation presence or absence. Ultimately choice of a nest site appears to be related to high-tide level and sand moisture level. Key words: Reptilia, Testudines, Cheloniidae, marine turtles, population size Introduction Although the occasional green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is found nesting on the granitic island of Cousine, Seychelles Republic, hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) form the bulk of the breeding population on the island, and any further reference to turtles is of this species. Little previous information has been published on marine turtles on Cousine Island except for an estimate of numbers of hawksbills believed to nest there (Frazier 1984), a brief general description of numbers and breeding (Bourquin & Hitchins 1998). -

EXCURSIONS – November 2020 to October 2021 in the Garden of Eden 2020-21 on Board the M/Y Pegasos

EXCURSIONS – November 2020 to October 2021 In the Garden of Eden 2020-21 on board the M/Y Pegasos PRASLIN - Duration approximately 3 ½ hours – Included: Private bus, Professional English speaking guide, all entrance fees € 94—per person The tour combines Praslin’s World Heritage Site, the Vallee De Mai Nature Reserve, and Cote D’ Or Beach, one of the most beautiful beaches in the Seychelles, if not the world. Discover the original Garden of Eden -the Vallee De Mai -home of the unique coco de mer (double coconut), bearing the largest nut in the plant kingdom. The rare Black Parrot also haunts the Reserve feeding on the abundant fruit. This World Heritage Site is a magical forest, thick with wild tropical vegetation, and many species of rare, endemic palms. Refreshments are served at Cote D’ Or Beach where time is allocated for swimming, relaxing or simply strolling on the beach. LA DIGUE - Duration approximately 3 ½ hours Included: Drive on camionette exclusively for Pegasos guests, English speaking guide, entry fees € 73—per person Experience the Old World beauty and charm of the Seychelles during an orientation tour of the picturesque La Digue, one of the prettiest islands in the Seychelles. On our scenic drive from La Passe Harbor to L’ Union Estate you will daily life to be punctuated by ox carts and a relaxed pace. Upon arrival at L’ Union Estate you will see its old Creole house and coconut factory: a reminder of how life was on the island many years ago. We continue to La Digue’s famous beaches, which are considered to be amongst the finest in the world, especially Anse Source d’ Argent, a bather’s paradise and photographer’s dream. -

The Impact of Conservation-Driven Translocations on Blood Parasite Prevalence in the Seychelles Warbler

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The impact of conservation-driven translocations on blood parasite prevalence in the Seychelles Received: 22 December 2015 Accepted: 22 June 2016 warbler Published: 13 July 2016 Eleanor A. Fairfield1, Kimberly Hutchings1,2, Danielle L. Gilroy1, Sjouke A. Kingma2, Terry Burke3, Jan Komdeur2 & David S. Richardson1,4 Introduced populations often lose the parasites they carried in their native range, but little is known about which processes may cause parasite loss during host movement. Conservation-driven translocations could provide an opportunity to identify the mechanisms involved. Using 3,888 blood samples collected over 22 years, we investigated parasite prevalence in populations of Seychelles warblers (Acrocephalus sechellensis) after individuals were translocated from Cousin Island to four new islands (Aride, Cousine, Denis and Frégate). Only a single parasite (Haemoproteus nucleocondensus) was detected on Cousin (prevalence = 52%). This parasite persisted on Cousine (prevalence = 41%), but no infection was found in individuals hatched on Aride, Denis or Frégate. It is not known whether the parasite ever arrived on Aride, but it has not been detected there despite 20 years of post-translocation sampling. We confirmed that individuals translocated to Denis and Frégate were infected, with initial prevalence similar to Cousin. Over time, prevalence decreased on Denis and Frégate until the parasite was not found on Denis two years after translocation, and was approaching zero prevalence on Frégate. The loss (Denis) or decline (Frégate) of H. nucleocondensus, despite successful establishment of infected hosts, must be due to factors affecting parasite transmission on these islands. Across a wide range of host taxa, parasite diversity and abundance is lower in introduced compared to native populations1,2. -

Hawksbill Turtle Monitoring in Cousin Island Special Reserve, Seychelles: an Eight-Fold Increase in Annual Nesting Numbers

Vol. 11: 195–200, 2010 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online April 30 doi: 10.3354/esr00281 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Hawksbill turtle monitoring in Cousin Island Special Reserve, Seychelles: an eight-fold increase in annual nesting numbers Zoë C. Allen1,*, Nirmal J. Shah1, Alastair Grant2, Gilles-David Derand1, Diana Bell2 1Nature Seychelles, PO Box 1310, The Centre for Environment & Education, Roche Caiman, Mahe, Seychelles 2School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Norfolk NR4 7TJ, UK ABSTRACT: Results of hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata nest monitoring on Cousin Island, Seychelles, indicate an 8-fold increase in abundance of nesting females since the early 1970s when the population was highly depleted. From 1999 to 2009, the population increased at an average rate of 16.5 turtles per season. Females were individually tagged, and nesting data were derived from indirect evidence of nesting attempts (i.e. tracks) and actual turtle sightings (56 to 60% of all encoun- ters). Survey effort varied over the years for a variety of reasons, but the underlying trends over time are considered robust. To overcome biases associated with variable survey effort, we estimated pop- ulation changes by fitting a Poisson distribution to data on numbers of times each individual was seen at this breeding site in a season. This was used to estimate unseen individuals, and hence the total number of nesting females each season. The maximum number of individuals emerging onto Cousin Island to nest within a single season was estimated to be 256 (2007 to 2008) compared to 23 in 1973. Tag returns indicate that many turtles nest on both Cousin and Cousine Islands (2 km apart), and that some inter-island nesting also occurs between Cousin and more remote islands within the Seychelles. -

Seychelles National Report Phase 1: Integrated Problem Analysis

Global Environment Facility GEF MSP Sub-Saharan Africa Project (GF/6010-0016): “Development and Protection of the Coastal and Marine Environment in Sub-Saharan Africa” SEYCHELLES NATIONAL REPORT PHASE 1: INTEGRATED PROBLEM ANALYSIS Terry Jones (National Coordinator), Rolph Payet, Katy Beaver and Michel Nalletamby March 2002 Disclaimer: The content of this document represents the position of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views or official policies of the Government of Seychelles, ACOPS, IOC/UNESCO or UNEP. The components of the GEF MSP Sub-Saharan Africa Project (GF/6010-0016) "Development and Protection of the Coastal and Marine Environment in Sub-Saharan Africa" have been supported, in cash and kind, by GEF, UNEP, IOC-UNESCO, the GPA Coordination Office and ACOPS. Support has also been received from the Governments of Canada, The Netherlands, Norway, United Kingdom and the USA, as well as the Governments of Côte d'Ivoire, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa and Tanzania. Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. i Seychelles Country Profile................................................................................................................... ixv Chapter 1 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................1 1.1 Population and Economy .......................................................................................................1 -

Eradication of Invasive Common Mynas Acridotheres Tristis from North Island, Seychelles, with Recommendations for Planning Eradication Attempts Elsewhere

Management of Biological Invasions (2021) Volume 12, Issue 3: 700–715 CORRECTED PROOF Management in Practice Eradication of invasive common mynas Acridotheres tristis from North Island, Seychelles, with recommendations for planning eradication attempts elsewhere Chris J. Feare1,*, Jeremy Waters2, Sarah R. Fenn2,3, Christine S. Larose4, Tarryn Retief2, Carl Havemann2, Per-Arne Ahlen5, Claire Waters2,6, Maxine K. Little2,7, Sarah Atkinson2,8, Bethan Searle2,9, Elliot Mokhobo2, Arjan de Groene10,11 and Wilna Accouche10 1WildWings Bird Management, 2 North View Cottages, Grayswood Common, Haslemere, Surrey GU27 2DN, UK 2North Island, Seychelles 3Present address: School of Biological Sciences, Zoology Building, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK 4WildWings Bird Management, Pointe au Sel, Mahe, Seychelles 5Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management, Öster-Malma, Nyköping, Sweden 6Present address: Cousin Island, Seychelles 7Present address: School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia 8Present address: Orkney Native Wildlife Project, H24 Garrison Road, Hatston Industrial Estate, Kirkwall, Orkney Islands, KW15 1PG, UK 9RSPB England, Exeter Office, 4th Floor (North Block), Broadwalk House, Southernhay West, Exeter, Devon, EX1 1TS 10Green Islands Foundation, Victoria, Mahe, Seychelles 11Present address: WWF-NL, Zeist, The Netherlands Author e-mails: [email protected] (CJF), [email protected] (JW), [email protected] (SRF), [email protected] (CSL), [email protected]