Harp Healing Gwers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celtic Solar Goddesses: from Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven

CELTIC SOLAR GODDESSES: FROM GODDESS OF THE SUN TO QUEEN OF HEAVEN by Hayley J. Arrington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Women’s Spirituality Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California June 8, 2012 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this thesis: ________________________________________________ __________________ Judy Grahn, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ __________________ Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Copyright © Hayley Jane Arrington 2012 All Rights Reserved Formatted according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition ii Abstract Celtic Solar Goddesses: From Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven by Hayley J. Arrington Utilizing a feminist hermeneutical inquiry, my research through three Celtic goddesses—Aine, Grian, and Brigit—shows that the sun was revered as feminine in Celtic tradition. Additionally, I argue that through the introduction and assimilation of Christianity into the British Isles, the Virgin Mary assumed the same characteristics as the earlier Celtic solar deities. The lands generally referred to as Celtic lands include Cornwall in Britain, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Brittany in France; however, I will be limiting my research to the British Isles. I am examining these three goddesses in particular, in relation to their status as solar deities, using the etymologies of their names to link them to the sun and its manifestation on earth: fire. Given that they share the same attributes, I illustrate how solar goddesses can be equated with goddesses of sovereignty. Furthermore, I examine the figure of St. -

Rhythm Bones Player a Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No

Rhythm Bones Player A Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No. 3 2008 In this Issue The Chieftains Executive Director’s Column and Rhythm As Bones Fest XII approaches we are again to live and thrive in our modern world. It's a Bones faced with the glorious possibilities of a new chance too, for rhythm bone players in the central National Tradi- Bones Fest in a new location. In the thriving part of our country to experience the camaraderie tional Country metropolis of St. Louis, in the ‗Show Me‘ state of brother and sisterhood we have all come to Music Festival of Missouri, Bones Fest XII promises to be a expect of Bones Fests. Rhythm Bones great celebration of our nation's history, with But it also represents a bit of a gamble. We're Update the bones firmly in the center of attention. We betting that we can step outside the comfort zones have an opportunity like no other, to ride the where we have held bones fests in the past, into a Dennis Riedesel great Mississippi in a River Boat, and play the completely new area and environment, and you Reports on bones under the spectacular arch of St. Louis. the membership will respond with the fervor we NTCMA But this bones Fest represents more than just have come to know from Bones Fests. We're bet- another great party, with lots of bones playing ting that the rhythm bone players who live out in History of Bones opportunity, it's a chance for us bone players to Missouri, Kansas, Illinois, Oklahoma, and Ne- in the US, Part 4 relive a part of our own history, and show the braska will be as excited about our foray into their people of Missouri that rhythm bones continue (Continued on page 2) Russ Myers’ Me- morial Update Norris Frazier Bones and the Chieftains: a Musical Partnership Obituary What must surely be the most recognizable Paddy Maloney. -

Compton Music Stage

COMPTON STAGE-Saturday, Sept. 18, FSU Upper Quad 10:20 AM Bear Hill Bluegrass Bear Hill Bluegrass takes pride in performing traditional bluegrass and gospel, while adding just the right mix of classic country and comedy to please the audience and have fun. They play the familiar bluegrass, gospel and a few country songs that everyone will recognize, done in a friendly down-home manner on stage. The audience is involved with the band and the songs throughout the show. 11:00 AM The Jesse Milnes, Emily Miller, and Becky Hill Show This Old-Time Music Trio re-envisions percussive dance as another instrument and arrange traditional old-time tunes using foot percussion as if it was a drum set. All three musicians have spent significant time in West Virginia learning from master elder musicians and dancers and their goal with this project is to respect the tradition the have steeped themselves in while pushing the boundaries of what old-time music is. 11:45 AM Ken & Brad Kolodner Quartet Regarded as one of the most influential hammered dulcimer players, Baltimore’s Ken Kolodner has performed and toured for the last ten years with his son Brad Kolodner, one of the finest practitioners of the clawhammer banjo, to perform tight and musical arrangements of original and traditional old-time music with a “creative curiosity that lets all listeners know that a passion for traditional music yet thrives in every generation (DPN).” The dynamic father-son duo pushes the boundaries of the Appalachian tradition by infusing their own brand of driving, innovative, tasteful and unique interpretations of traditional and original fiddle tunes and songs. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

Traditions Music Black Secularnon-Blues

TRADITIONS NON-BLUES SECULAR BLACK MUSIC THREE MUSICIANS PLAYING ACCORDION, BONES, AND JAWBONE AT AN OYSTER ROAST, CA. 1890. (Courtesy Archives, Hampton Institute) REV JAN 1976 T & S-178C DR. NO. TA-1418C © BRI Records 1978 NON-BLUES SECULAR BLACK MUSIC been hinted at by commercial discs. John Lomax grass, white and black gospel music, songs for IN VIRGINIA and his son, Alan, two folksong collectors with a children, blues and one anthology, Roots O f The Non-blues secular black music refers to longstanding interest in American folk music, Blues devoted primarily to non-blues secular ballads, dance tunes, and lyric songs performed began this documentation for the Library of black music (Atlantic SD-1348). More of Lomax’s by Afro-Americans. This music is different from Congress in 1933 with a trip to the State recordings from this period are now being issued blues, which is another distinct form of Afro- Penitentiary in Nashville, Tennessee. On subse on New World Records, including Roots Of The American folk music that developed in the deep quent trips to the South between 1934 and 1942, Blues (New World Records NW-252). * South sometime in the 1890s. Blues is character the Lomaxes cut numerous recordings, often at In recent years the emphasis of most field ized by a twelve or eight bar harmonic sequence state prisons, from Texas to Virginia.2 They researchers traveling through the South in search and texts which follow an A-A-B stanza form in found a surprising variety of both Afro-American of Afro-American secular music has been on the twelve bar pattern and an A-B stanza form in and Anglo-American music on their trips and blues, although recorded examples of non-blues the eight bar pattern. -

Country Dance and Song and Society of America

I ,I , ) COUNTRY DANCE 1975 Number 7 Published by The Country Dance and Song AND Society of America EDITOR J. Michael Stimson SONG COUNTRY DANCE AND SONG is published annually. Subscription is by membership in the Society. Members also receive occasional newsletters. Annual dues are $8 . 00 . Libraries, Educational Organi zations, and Undergraduates, , $5.00. Please send inquiries to: Country Dance and Song Society, 55 Christopher Street, New York, NY 10014. We are always glad to receive articles for publication in this magazine dealing with the past, present or future of traditional dance and music in England and America, or on related topics . PHOTO CREDITS P. 5 w. Fisher Cassie P. 12 (bottom) Suzanne Szasz P. 26 William Garbus P. 27 William Garb us P. 28 William Garb us CONTENTS AN INTERVIEW WITH MAY GADD 4 TRADITION, CHANGE AND THE SOCIETY Genevieve Shimer ........... 9 SQUARE DANCING AT MARYLAND LINE Robert Dalsemer. 15 Copyright€>1975 by Country Dance Society, Inc. SONGFEST AND SLUGFEST: Traditional Ballads and American Revolutionary Propaganda Estelle B. Wade. 20 , CDSS REVISITS COLONIAL ERA • . • . • . • . • • . 26 TWO DANCES FROM THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA Researched by James Morrison ..................••. 29 CHEERILY AND MERRILLY: Our Music Director's Way with Singing Games and Children Joan Carr.............. 31 STAFF AND LEADERS'CONFERENCE Marshall Barron .•.......... 35 SALES James Morrison ............. 40 CDSS CENTERS .•......•.............•••.. 49 A: Well, they didn't have bands so much. Cecil Sharp was a mar velous piano player, AN INTERVIEW WITH and he had a wonder ful violinist, Elsie Avril, who played with him right from the be MAY GADD... ginning. We had just piano and violin in those days for all but the big theater This is the first part of an interview by Joseph Hickerson, performances. -

Download Booklet

Heavenly Harp BEST LOVED classical harp music Heavenly Harp Best loved classical harp music 1 Alphonse HASSELMANS (1845–1912) 10 Henriette RENIÉ (1875–1956) La Source, Op. 44 3:55 Danse des Lutins 3:59 Erica Goodman (8.573947) Judy Loman (8.554347) 2 Hugo REINHOLD (1854–1935) 11 Marcel TOURNIER (1879–1951) Impromptu in C sharp minor, Op. 28, No. 3 5:35 Vers la source dans le bois 4:18 Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) (‘Towards the Fountain in the Wood’) Judy Loman (8.554561) 3 John THOMAS (1826–1913) Dyddiau Mebyd (‘Scenes of Childhood’) – 3:05 12 Gabriel FAURÉ (1845–1924) II. Toriad y Dydd (‘The Dawn of Day’) Une chatelaine en sa tour, Op. 110 4:41 Lipman Harp Duo (8.570372) Judy Loman (8.554561) 4 Gaetano DONIZETTI (1797–1848) 13 Elias PARISH ALVARS (1808–1849) Lucia di Lammermoor, Act 1 Scene 2 4:25 Serenade, Op. 83 – Serenade 7:13 (arr. A.H. Zabel) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) 14 Gabriel PIERNÉ (1863–1937) 5 Marcel GRANDJANY (1891–1975) Impromptu-caprice, Op. 9 5:51 Fantasy on a Theme of Haydn, Op. 31 7:54 Ellen Bødtker (8.555328) Judy Loman (8.554561) 15 Nino ROTA (1911–1979) 6 Manuel de FALLA (1876–1946) Toccata 2:33 La vida breve, Act II – 4:11 Elisa Netzer (8.573835) Danse espagnole No. 1 (ver. For 2 guitars) Judy Loman (8.554561) 16 John PARRY (1710–1782) Sonata No. 2 – Siciliana 2:06 7 Sophia DUSSEK (1775–1847) Judy Loman (8.554347) Sonata – Allegro 2:39 Judy Loman (8.554347) 17 Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH (1714–1788) 12 Variations on La folia d’Espagne, 9:13 8 Louis SPOHR (1784–1859) Wq. -

FREE CONCERTS JOIN US for Music in the Garden Wednesdays at 7 P.M

FREE CONCERTS JOIN US FOR Music in the Garden Wednesdays at 7 p.m. in the Murie Building Auditorium Thursdays at 7 p.m. in the Georgeson Botanical Garden The Fairbanks Red Hackle Pipe Band Emily Anderson JULY 6 Emily’s a local Indie/Folk singer- songwriter and a graduate of Berklee College of Music. Her music, influenced by Carole King, Ingrid Michaelson, and Regina Spektor, MAY 25 For over thirty years this band has shared its love ranges from sentimental to humorous. for Highland piping, drumming, and dance. Dry Cabin String Band Headbolt Heaters JULY 13 Dry Cabin String Band JUNE 1 These three songwriters’ plays and sings hard driving, eclectic sound taps into roots, rock, traditional bluegrass, featuring blues, bluegrass and an underbelly guitar, fiddle, banjo, and bass. of punk. FSAF Celtic Ensemble O Tallulah JULY 20 Revel in the unique JUNE 8 This family trio of sights and sounds of singer-songwriters, home traditional Irish music with grown in the Golden Heart of tin whistle, Irish guitar, Alaska, performs classic bodhrán, Irish flute, bones and Irish dancing. country, folk and gospel. FSAF Brazilian Ensemble Marc Brown & The Blues Crew JULY 27 Jamie Maschler on JUNE 15 Marc, a Koyukon accordion and Finn Magill on Athabascan, and his band have 12 fiddle bring the lively spirit of CDs and have blown away regional Brazilian music to Fairbanks. and national competitions. Fairbanks Community Jazz Band Rock Bottom Stompers AUGUST 3 This traditional Big JUNE 22 Rock Bottom Stompers Band and its guests mix swing era bring to you soulful, stompable tunes dance tunes with Latin, Bop, and featuring sweet lonesome harmonies. -

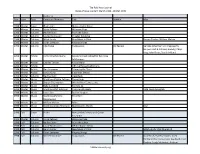

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998 Author or Year Issue Type Composer/Arranger Title Subtitle Misc 1998 Winter Cover Illustration Make a Joyful Noise 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Winter Column Laurie Rasmussen Chapter Roundup 1998 Winter Column Mitch Landy New Music in Print Harper Tasche; William Mahan 1998 Winter Column Dinah LeHoven Ringing Strings 1998 Winter Column Alys Howe Harpsounds CD Review Verlene Schermer; Lori Pappajohn; Harpers Hall & Culinary Society; Chrys King; John Doan; David Helfand 1998 Winter Article Patty Anne McAdams Second annual retreat for Bay Area folk harpers 1998 Winter Article Charles Tanner A Cool Harp! 1998 Winter Article Fifth Gulf Coast Celtic harp 1998 Winter Article Ann Heymann Trimming the Tune 1998 Winter Article James Kurtz Electronic Effects 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn Classifieds 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Sylvia Fellows Three Kings 1998 Winter Music Sharon Thormahlen Where River Turns to sky 1998 Winter Music Reba Lunsford Tootie's Jig 1998 Winter Music Traditional/M. Schroyer The Friendly Beats 12th Century English 1998 Winter Music Joyce Rice By Yon Yangtze 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Serena He is Born Underwood 1998 Winter Music William Mahan Adios 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Ann Heymann MacDonald's March Irish 1998 Fall Cover Photo New Zealand's Harp and Guitar Ensemble 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Fall Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Fall Column -

Paradigmatic of Folk Music Tradition?

‘Fiddlers’ Tunebooks’ - Vernacular Instrumental Manuscript Sources 1860-c1880: Paradigmatic of Folk Music Tradition? By: Rebecca Emma Dellow A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music June 2018 2 Abstract Fiddlers’ Tunebooks are handwritten manuscript books preserving remnants of a largely amateur, monophonic, instrumental practice. These sources are vastly under- explored academically, reflecting a wider omission in scholarship of instrumental music participated in by ‘ordinary’ people in nineteenth-century England. The tunebooks generate interest amongst current folk music enthusiasts, and as such can be subject to a “burden of expectation”,1 in the belief that they represent folk music tradition. Yet both the concepts of tradition and folk music are problematic. By considering folk music from both an inherited perspective and a modern scholarly interpretation, this thesis examines the place of the tunebooks in notions of English folk music tradition. A historical musicological methodology is applied to three post-1850 case-study manuscripts drawing specifically on source studies, archival research and quantitative analysis. The study explores compilers’ demographic traits and examines content, establishing the existence of a heterogeneous repertoire copied from contemporary textual sources directly into the tunebooks. This raises important questions regarding the role played by publishers and the concept of continuous survival in notions of tradition. A significant finding reveals the interaction between aural and literate practices, having important implications in the inward and outward transmission and in wider historical application. The function of both the manuscripts and the musical practice is explored and the compilers’ acquisition of skill and sources is examined. -

Internet Search 1999

Internet Research On Rhythm Bones October 1999 Steve Wixson 1060 Lower Brow Road Signal Mountain, TN 37377 423/886-1744 [email protected] Introduction This document presents the current state of 'bone playing' and includes the results of a web search using several search engines for 'rhythm bones', 'rattling bones' and 'bone playing'. It is fairly extensive, but obviously not complete. The web addresses are accurate at the time of the search, but they can go out of date quickly. Web information pertaining to bones was extracted from each website. Some of this information may be copyrighted, so anyone using it should check that out. Text in italics is from e-mail and telephone conversations. We would appreciate additions - please send to name at end of this document. The following is William Sidney Mount's 'The Bone Player.' A. General 1. http://mcowett.home.mindspring.com/BoneFest.html. 'DEM BONES, 'DEM BONES, 'DEM RHYTHM BONES! Welcome to Rhythm Bones Central The 1997 Bones Festival. Saturday September 20, 1997 was just another normal day at "the ranch". The flag was run up the pole at dawn, but wait -----, bones were hanging on the mail box. What gives? This turns out to be the 1st Annual Bones Festival (of the century maybe). Eleven bones-players (bone-player, boner, bonist, bonesist, osyonist, we can't agree on the name) and spouses or significant others had gathered by 1:00 PM to share bones-playing techniques, instruments and instrument construction material, musical preferences, to harmonize and to have great fun and fellowship. All objectives were met beyond expectations.