The King Mackerel, Scomberomorus Cavalla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEVELS in INDIAN MACKEREL Rastrelliger Kanagurta (SCOMBRIDAE) from KARACHI FISH HARBOUR and ITS RISK ASSESSMENT Quratulan Ahmed1,*, Levent Bat2

9(3): 012-016 (2015) Journal of FisheriesSciences.com E-ISSN 1307-234X © 2015 www.fisheriessciences.com ORIGINAL ARTICLE Research Article MERCURY (Hg) LEVELS IN INDIAN MACKEREL Rastrelliger kanagurta (SCOMBRIDAE) FROM KARACHI FISH HARBOUR AND ITS RISK ASSESSMENT Quratulan Ahmed1,*, Levent Bat2 1The Marine Reference Collection and Resources Centre, University of Karachi, Karachi, 75270 Pakistan 2University of Sinop, Fisheries Faculty, Department of Hydrobiology, TR57000 Sinop, Turkey Received: 03.04.2015 / Accepted: 24.04.2015 / Published online: 28.04.2015 Abstract: The present study was conducted to determine Hg levels in edible tissues of the Indian mackerel Rastrelliger kanagurta collected at Karachi Harbour of Pakistan between March 2013 and February 2014. Hg levels ranged from 0.01 to 0.09 with mean ± SD 0.042 ± 0.023 mg/kg dry wt. The Hg level in R. kanagurta is relatively low when compared to those studied in other parts of the world and is able to meet the legal standards by EU Commission Regulation and other international food standards. The findings obtained were also compared with established allowable weekly intake values. It is concluded that the Hg levels in the Indian mackerel from Karachi coasts did not exceed the permission limits (0.5 mg/kg). The results show that the Indian mackerel appears to be useful bio-indicator due to their accumulation of Hg, however, continued sampling is required for further researches. Keywords: Mercury, Rastrelliger kanagurta, Bio-indicator, Karachi fish harbour, Pakistan *Correspondence to: Quratulan Ahmed, The Marine Reference Collection and Resources Centre, University of Karachi, Karachi, 75270 Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +92 (345) 2983586 12 Journal of FisheriesSciences.com Ahmed Q and Bat L 9(3): 012-016 (2015) Journal abbreviation: J FisheriesSciences.com Introduction exposure route possibly allowing metal biomagnification up trophic levels in the Indian mackerel R. -

May-August 2008

~ UH-NOAA~ Volume 13, Number 2 May–August 2008 What If You Don’t Speak “CPUE-ese”? J. John Kaneko and Paul K. Bartram Introduction Seafood consumers are largely unaware of the environmental conse- quences they implicitly endorse when buying fish from different sources. To more effectively support responsible fisheries, consumers need to be able to easily differentiate seafood harvested in sustainable ways using more “envi- ronmentally friendly” methods from seafood from less sustainable origins. This requires easy access by con- sumers to easy-to-understand infor- mation comparing the “environmen- tal baggage” of competing suppliers of similar seafood products. Existing scientific measures do define such distinctions—but they are often too complex or technical to be easily understood or used by the aver- age seafood consumer. New communi- cation tools for readily conveying such information to non-scientist seafood consumers are needed. Figure 1. Computed Hawai‘i longline tuna fisheries bycatch-to-catch (B/C) ratios were reduced after increased (to greater than 20 percent of the annual fishing trips) observer coverage documented a lower rate of sea- turtle interaction than had the lower previous observer coverage (of less than 5 percent of the annual fishing Successful Efforts at Reducing trips). Sea-turtle interactions were significantly reduced in the Hawai‘i longline swordfish fishery as a result Sea-Turtle “Bycatch” of revised hook-and-bait requirements required by federal regulations that took effect in mid-2004. The Hawai‘i longline fishery, work- The area of the circles is proportional to the number of sea-turtle takes per 418,000 lb of target fish (tuna ing with fisheries scientists and fisheries or swordfish) caught. -

Diet of Wahoo, Acanthocybium Solandri, from the Northcentral Gulf of Mexico

Diet of Wahoo, Acanthocybium solandri, from the Northcentral Gulf of Mexico JAMES S. FRANKS, ERIC R. HOFFMAYER, JAMES R. BALLARD1, NIKOLA M. GARBER2, and AMBER F. GARBER3 Center for Fisheries Research and Development, Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, The University of Southern Mississippi, P.O. Box 7000, Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39566 USA 1Department of Coastal Sciences, The University of Southern Mississippi, P.O. Box 7000, Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39566 USA 2U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Sea Grant, 1315 East-West Highway, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 USA 3Huntsman Marine Science Centre, 1Lower Campus Road, St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada E5B 2L7 ABSTRACT Stomach contents analysis was used to quantitatively describe the diet of wahoo, Acanthocybium solandri, from the northcen- tral Gulf of Mexico. Stomachs were collected opportunistically from wahoo (n = 321) that were weighed (TW, kg) and measured (FL, mm) at fishing tournaments during 1997 - 2007. Stomachs were frozen and later thawed for removal and preservation (95% ethanol) of contents to facilitate their examination and identification. Empty stomachs (n = 71) comprised 22% of the total collec- tion. Unfortunately, the preserved, un-examined contents from 123 stomachs collected prior to Hurricane Katrina (August 2005) were destroyed during the hurricane. Consequently, assessments of wahoo stomach contents reported here were based on the con- tents of the 65 ‘pre-Katrina’ stomachs, in addition to the contents of 62 stomachs collected ‘post-Katrina’ during 2006 and 2007, for a total of 127 stomachs. Wahoo with prey in their stomachs ranged 859 - 1,773 mm FL and 4.4 - 50.4 kg TW and were sexed as: 31 males, 91 females and 5 sex unknown. -

Ecography ECOG-01937 Hattab, T., Leprieur, F., Ben Rais Lasram, F., Gravel, D., Le Loc’H, F

Ecography ECOG-01937 Hattab, T., Leprieur, F., Ben Rais Lasram, F., Gravel, D., Le Loc’h, F. and Albouy, C. 2016. Forecasting fine- scale changes in the food-web structure of coastal marine communities under climate change. – Ecography doi: 10.1111/ecog.01937 Supplementary material Forecasting fine-scale changes in the food-web structure of coastal marine communities under climate change by Hattab et al. Appendix 1 List of coastal exploited marine species considered in this study Species Genus Order Family Class Trophic guild Auxis rochei rochei (Risso, 1810) Auxis Perciformes Scombridae Actinopterygii Top predators Balistes capriscus Gmelin, 1789 Balistes Tetraodontiformes Balistidae Actinopterygii Macro-carnivorous Boops boops (Linnaeus, 1758) Boops Perciformes Sparidae Actinopterygii Basal species Carcharhinus plumbeus (Nardo, 1827) Carcharhinus Carcharhiniformes Carcharhinidae Elasmobranchii Top predators Dasyatis pastinaca (Linnaeus, 1758) Dasyatis Rajiformes Dasyatidae Elasmobranchii Top predators Dentex dentex (Linnaeus, 1758) Dentex Perciformes Sparidae Actinopterygii Macro-carnivorous Dentex maroccanus Valenciennes, 1830 Dentex Perciformes Sparidae Actinopterygii Macro-carnivorous Diplodus annularis (Linnaeus, 1758) Diplodus Perciformes Sparidae Actinopterygii Forage species Diplodus sargus sargus (Linnaeus, 1758) Diplodus Perciformes Sparidae Actinopterygii Macro-carnivorous (Geoffroy Saint- Diplodus vulgaris Hilaire, 1817) Diplodus Perciformes Sparidae Actinopterygii Basal species Engraulis encrasicolus (Linnaeus, 1758) Engraulis -

Status and Prospects of Mackerel and Tuna Fishery in Bangladesh

Status and prospects of mackerel and tuna fishery in Bangladesh Item Type article Authors Rahman, M.J.; Zaher, M. Download date 27/09/2021 01:00:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/34189 Bangladesh]. Fish. Res.) 10(1), 2006: 85-92 Status and prospects of mackerel and tuna fishery in Bangladesh M. J. Rahman* and M. Zaher1 Marine Fisheries & Technology Station, Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute Cox's Bazar 4700, Bangladesh 1Present address: BFRI, Freshwater Station, Mvmensingh 2201, Bangladesh *Corresponding author Abstract Present status and future prospects of mackerel and tuna fisheries in Bangladesh were assessed during July 2003-June 2004. The work concentrated on the fishing gears, length of fishes, total landings and market price of the catch and highlighted the prospects of the fishery in Bangladesh. Four commercially important species of mackerels and tuna viz. Scomberomorus guttatus, Scomberomorus commerson, Rastrelliger kanagurta, and Euthynnus affinis were included in the study. About 95% of mackerels and tuna were caught by drift gill nets and the rest were caught by long lines ( 4%) and marine set-bag-net (1 %). Average monthly total landing of mackerels and tunas was about 264 t, of which 147 t landed in Cox's Bazar and 117 tin Chittagong sites. Total catches of the four species in Cox's Bazar and Chittagong sites were found to be 956 and 762 t, respectively. The poor landing was observed during January-February and the peak landing was in November and July. Gross market value of the annual landing of mackerels and tunas (1,718 t) was found to be 1,392 lakh taka. -

King Mackerel, Scomberomorus Caval/A, Mark-Recapture Studies Off Florida's East Coast

King Mackerel, Scomberomorus cavalla, Mark- Recapture Studies Off Florida's East Coast Item Type article Authors Schaefer, H. Charles; Fable, Jr. , William A. Download date 04/10/2021 08:14:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/26474 King Mackerel, Scomberomorus caval/a, Mark-Recapture Studies Off Florida's East Coast H. CHARLES SCHAEFER and WILLIAM A. FABLE, JR. Introduction reproductive capacity causing stock re Panama City Laboratory, began a co ductions and declining recruitment operative mark-recapture study on king King mackerel, Scomberomorus cav (Godcharles I). King mackerel have mackerel to determine movements in alla, is a coastal, pelagic scombrid been jointly managed by the South At both the Gulf of Mexico and along the found off the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of lantic and Gulf of Mexico Fishery Man Atlantic coast. Subsequently, biologists Mexico coasts. This species has histori agement Councils since the implemen from both agencies tagged king mack cally contributed to commercial and tation of the Coastal Pelagic Fishery erel (17,042 releases, 1,171 returns) recreational catches throughout its Management Plan (CPFMP) in 1983. from 1975 through 1979 (Sutherland range in the southeastern United States. The maximum sustainable yield (MSY) and Fable, 1980; Sutter et aI., 1991; Commercial exploitation intensified for the U.S. king mackerel resource is Williams and Godcharles3). Results there in the 1960's with the introduc currently estimated at 26.2 million from this study indicated that the spe tion of large power-assisted gillnet pounds (NMFS2). cies consisted of at least two migratory boats and spotter aircraft. -

Daily Ration of Japanese Spanish Mackerel Scomberomorus Niphonius Larvae

FISHERIES SCIENCE 2001; 67: 238–245 Original Article Daily ration of Japanese Spanish mackerel Scomberomorus niphonius larvae J SHOJI,1,* T MAEHARA,2,a M AOYAMA,1 H FUJIMOTO,3 A IWAMOTO3 AND M TANAKA1 1Laboratory of Marine Stock-enhancement Biology, Division of Applied Biosciences, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, 2Toyo Branch, Ehime Prefecture Chuyo Fisheries Experimental Station, Toyo, Ehime 799-1303, and 3Yashima Station, Japan Sea-farming Association, Takamatsu, Kagawa 761-0111, Japan SUMMARY: Diel successive samplings of Japanese Spanish mackerel Scomberomorus niphonius larvae were conducted throughout 24 h both in the sea and in captivity in order to estimate their daily ration. Using the Elliott and Persson model, the instantaneous gastric evacuation rate was estimated from the depletion of stomach contents (% dry bodyweight) with time during the night for wild fish (3.0–11.5 mm standard length) and from starvation experiments for reared fish (8, 10, and 15 days after hatching (DAH)). Japanese Spanish mackerel is a daylight feeder and exhibited piscivorous habits from first feeding both in the sea and in captivity. Feeding activity peaked at dusk. The esti- mated daily ration for wild larvae were 111.1 and 127.2% in 1996 and 1997, respectively; and those for reared larvae ranged from 90.6 to 111.7% of dry bodyweight. Based on the estimated value of daily rations for reared fish, the total number of newly hatched red sea bream Pagrus major larvae preyed by a Japanese Spanish mackerel from first feeding (5 DAH) to beginning of juvenile stage (20 DAH) in captivity was calculated to be 1139–1404. -

Fisheries of the Northeast

FISHERIES OF THE NORTHEAST AMERICAN BLUE LOBSTER BILLFISHES ATLANTIC COD MUSSEL (Blue marlin, Sailfish, BLACK SEA BASS Swordfish, White marlin) CLAMS DRUMS BUTTERFISH (Arc blood clam, Arctic surf clam, COBIA Atlantic razor clam, Atlantic surf clam, (Atlantic croaker, Black drum, BLUEFISH (Gulf butterfish, Northern Northern kingfish, Red drum, Northern quahog, Ocean quahog, harvestfish) CRABS Silver sea trout, Southern kingfish, Soft-shelled clam, Stout razor clam) (Atlantic rock crab, Blue crab, Spot, Spotted seatrout, Weakfish) Deep-sea red crab, Green crab, Horseshoe crab, Jonah crab, Lady crab, Northern stone crab) GREEN SEA FLATFISH URCHIN EELS (Atlantic halibut, American plaice, GRAY TRIGGERFISH HADDOCK (American eel, Fourspot flounder, Greenland halibut, Conger eel) Hogchoker, Southern flounder, Summer GROUPERS flounder, Winter flounder, Witch flounder, (Black grouper, Yellowtail flounder) Snowy grouper) MACKERELS (Atlantic chub mackerel, MONKFISH HAKES JACKS Atlantic mackerel, Bullet mackerel, King mackerel, (Offshore hake, Red hake, (Almaco jack, Amberjack, Bar Silver hake, Spotted hake, HERRINGS jack, Blue runner, Crevalle jack, Spanish mackerel) White hake) (Alewife, Atlantic menhaden, Atlantic Florida pompano) MAHI MAHI herring, Atlantic thread herring, Blueback herring, Gizzard shad, Hickory shad, Round herring) MULLETS PORGIES SCALLOPS (Striped mullet, White mullet) POLLOCK (Jolthead porgy, Red porgy, (Atlantic sea Scup, Sheepshead porgy) REDFISH scallop, Bay (Acadian redfish, scallop) Blackbelly rosefish) OPAH SEAWEEDS (Bladder -

IATTC-94-01 the Tuna Fishery, Stocks, and Ecosystem in the Eastern

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION 94TH MEETING Bilbao, Spain 22-26 July 2019 DOCUMENT IATTC-94-01 REPORT ON THE TUNA FISHERY, STOCKS, AND ECOSYSTEM IN THE EASTERN PACIFIC OCEAN IN 2018 A. The fishery for tunas and billfishes in the eastern Pacific Ocean ....................................................... 3 B. Yellowfin tuna ................................................................................................................................... 50 C. Skipjack tuna ..................................................................................................................................... 58 D. Bigeye tuna ........................................................................................................................................ 64 E. Pacific bluefin tuna ............................................................................................................................ 72 F. Albacore tuna .................................................................................................................................... 76 G. Swordfish ........................................................................................................................................... 82 H. Blue marlin ........................................................................................................................................ 85 I. Striped marlin .................................................................................................................................... 86 J. Sailfish -

© Iccat, 2007

A5 By-catch Species APPENDIX 5: BY-CATCH SPECIES A.5 By-catch species By-catch is the unintentional/incidental capture of non-target species during fishing operations. Different types of fisheries have different types and levels of by-catch, depending on the gear used, the time, area and depth fished, etc. Article IV of the Convention states: "the Commission shall be responsible for the study of the population of tuna and tuna-like fishes (the Scombriformes with the exception of Trichiuridae and Gempylidae and the genus Scomber) and such other species of fishes exploited in tuna fishing in the Convention area as are not under investigation by another international fishery organization". The following is a list of by-catch species recorded as being ever caught by any major tuna fishery in the Atlantic/Mediterranean. Note that the lists are qualitative and are not indicative of quantity or mortality. Thus, the presence of a species in the lists does not imply that it is caught in significant quantities, or that individuals that are caught necessarily die. Skates and rays Scientific names Common name Code LL GILL PS BB HARP TRAP OTHER Dasyatis centroura Roughtail stingray RDC X Dasyatis violacea Pelagic stingray PLS X X X X Manta birostris Manta ray RMB X X X Mobula hypostoma RMH X Mobula lucasana X Mobula mobular Devil ray RMM X X X X X Myliobatis aquila Common eagle ray MYL X X Pteuromylaeus bovinus Bull ray MPO X X Raja fullonica Shagreen ray RJF X Raja straeleni Spotted skate RFL X Rhinoptera spp Cownose ray X Torpedo nobiliana Torpedo -

Chromosomal Evolution in Large Pelagic Oceanic Apex Predators, the Barracudas (Sphyraenidae, Percomorpha)

Chromosomal evolution in large pelagic oceanic apex predators, the barracudas (Sphyraenidae, Percomorpha) R.X. Soares1, M.B. Cioffi2, L.A.C. Bertollo2, A.T. Borges1, G.W.W.F. Costa1 and W.F. Molina1 1Departamento de Biologia Celular e Genética, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Campus Universitário, Natal, RN, Brasil 2Departamento de Genética e Evolução, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brasil Corresponding author: W.F. Molina E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 16 (2): gmr16029644 Received February 14, 2017 Accepted March 8, 2017 Published April 20, 2017 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/gmr16029644 Copyright © 2017 The Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) 4.0 License. ABSTRACT. Sphyraena (barracudas) represents the only genus of the Sphyraenidae family and includes 27 species distributed into the tropical and subtropical oceanic regions. These pelagic predators can reach large sizes and, thus, attracting significant interest from commercial and sport fishing. Evolutionary data for this fish group, as well its chromosomal patterns, are very incipient. In the present study, the species Sphyraena guachancho, S. barracuda, and S. picudilla were analyzed under conventional (Giemsa staining, C-banding, and Ag- NOR) and molecular (CMA3 banding, and in situ hybridization with 18S rDNA, 5S rDNA, and telomeric probes) cytogenetic methods. The karyotypic patterns contrast with the current phylogenetic relationships proposed for this group, showing by themselves to be distinct among closely related species, and similar among less related ones. This indicates homoplasic characteristics, with similar karyotype patterns Genetics and Molecular Research 16 (2): gmr16029644 R.X. -

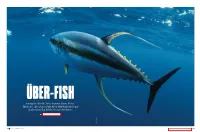

Among the World's Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also

ÜBER-FISH Among the World’s Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also Some of the Most Highly Evolved and Sophisticated of All the Ocean’s Predators BY DOUG OLANDER DANIEL GOEZ DANIEL 74 DECEMBER 2017 SPORTFISHINGMAG.COM 75 The Family Tree minimizes drag with a very low reduce the turbulence in the Tunas are part of the family drag coefficient,” optimizing effi- water ahead of the tail. Scombridae, which also includes cient swimming both at cruise Unlike most fishes with broad, mackerels, large and small. But and burst. While most fishes bend flexible tails that bend to scoop there are tunas, and then there their bodies side to side when water to move a fish forward, are, well, “true tunas.” moving forward, tunas’ bodies tunas derive tremendous That is, two groups don’t bend. They’re essentially thrust with thin, hard, lunate WHILE MOST FISHES BEND ( sometimes known as “tribes”) rigid, solid torpedoes. ( crescent-moon-shaped) tails dominate the tuna clan. One is And these torpedoes are that beat constantly, capable of THEIR BODIES SIDE TO SIDE Thunnini, which is the group perfectly streamlined, their 10 to 12 or more beats per second. considered true tunas, charac- larger fins fitting perfectly into That relentless thrust accounts WHEN MOVING FORWARD, terized by two separate dorsal grooves so no part of these fins for the unstoppable runs that fins and a relatively thick body. a number of highly specialized protrudes above the body surface. tuna make repeatedly when TUNAS’ BODIES DON’T BEND. The 15 species of Thunnini are features facilitate these They lack the convex eyes of hooked.