Thesis Program Stine Bundgaard Larsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allometric Equations for Estimating Biomass of Euterpe Precatoria, the Most Abundant Palm Species in the Amazon

Forests 2015, 6, 450-463; doi:10.3390/f6020450 OPEN ACCESS forests ISSN 1999-4907 www.mdpi.com/journal/forests Article Allometric Equations for Estimating Biomass of Euterpe precatoria, the Most Abundant Palm Species in the Amazon Fernando Da Silva 1,†, Rempei Suwa 2,†,*, Takuya Kajimoto 3, Moriyoshi Ishizuka 3, Niro Higuchi 1 and Norbert Kunert 1,4,† 1 Brazilian National Institute for Research in the Amazon, Laboratory for Forest Management, Manaus 69.060-000, Brazil; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.S.F.); [email protected] (H.N.); [email protected] (K.N.) 2 Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, Kansai Research Center, 68 Nagaikyutaroh, Momoyama, Fushimi, Kyoto 612-0855, Japan 3 Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, Matsunosato, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan; E-Mails: [email protected] (K.T.); [email protected] (I.M.) 4 Department for Biogeochemical Processes, Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Hans Knöll Str. 10, Jena 07745, Germany † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-90-9782-6042; Fax: +81-75-611-1207. Academic Editors: Michael Battaglia and Eric J. Jokela Received: 25 November 2014 / Accepted: 2 February 2015 / Published: 10 February 2015 Abstract: Allometric models to estimate biomass components such as stem mass Ms, foliage mass Ml, root mass Mr and aboveground mass Ma, were developed for the palm species Euterpe precatoria Mart., which is the most abundant tree species in the Amazon. We harvested twenty palms including above- and below-ground parts in an old growth Amazonian forest in Brazil. -

Fruit Trees and Useful Plants in Amazonian Life (2011)

FAO TECHNICAL PAPERS NON-WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 1. Flavours and fragrances of plant origin (1995) 2. Gum naval stores: turpentine and rosin from pine resin (1995) 3. Report of the International Expert Consultation on Non-Wood Forest Products (1995) 4. Natural colourants and dyestuffs (1995) 5. Edible nuts (1995) 6. Gums, resins and latexes of plant origin (1995) 7. Non-wood forest products for rural income and sustainable forestry (1995) 8. Trade restrictions affecting international trade in non-wood forest products (1995) 9. Domestication and commercialization of non-timber forest products in agroforestry systems (1996) 10. Tropical palms (1998) 11. Medicinal plants for forest conservation and health care (1997) 12. Non-wood forest products from conifers (1998) 13. Resource assessment of non-wood forest products Experience and biometric principles (2001) 14. Rattan – Current research issues and prospects for conservation and sustainable development (2002) 15. Non-wood forest products from temperate broad-leaved trees (2002) 16. Rattan glossary and Compendium glossary with emphasis on Africa (2004) 17. Wild edible fungi – A global overview of their use and importance to people (2004) 18. World bamboo resources – A thematic study prepared in the framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005 (2007) 19. Bees and their role in forest livelihoods – A guide to the services provided by bees and the sustainable harvesting, processing and marketing of their products (2009) 20. Fruit trees and useful plants in Amazonian life (2011) The -

Introduction

Introduction In order to commemorate the centenary of Roger Casement’s first voyage to the Amazon, this special issue of ABEI Journal No. 12 focuses on one of the most controversial figures of the 1916 Easter Rising. Roger Casement played an important role during the Amazon rubber boom and his writings about his Brazilian expeditions may be placed in the wider context of antislavery activism. He was British Consul in Santos (September 1906 - January 1908), in Belém do Pará (February 1908 - February 1909) and Consul-General in Rio de Janeiro (March 1909 - August 1913). In 1910, he travelled to the Amazon, commissioned by the British Government to investigate crimes against humanity being committed on the border between Peru, Colombia and Brazil. The story of the rubber industry connects the Amazon to central Africa during the reign of King Leopold II of Belgium, and to the commercial hubs of the industrialised world at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Rubber belongs to the celebratory narratives of western modernization and was a central issue in the Amazon where it acquired tragic proportions. It has also changed various regions of the world as a result of acts of violence practiced against the indigenous communities inhabiting the tropical rainforests. In August 2010 the W. B. Yeats Chair of Irish Studies at the University of São Paulo, the Brazilian Association of Irish Studies and the Federal University of Amazonas organized the first international interdisciplinary symposium on Roger Casement in Manaus, taking as its focus his 1910 voyage to the Putumayo. Co-organised by Laura Izarra, Angus Mitchell and Luiz Bitton Telles da Rocha, the conference discussed key aspects of Transatlantic and Latin American relations involved in the complicated politics of the Amazon rubber boom, as well as Roger Casement’s political and literary legacy. -

Plan a Learning Adventure for Your Group

PRIVATE GROUP CHARTERS Plan a Learning Adventure for Your Group Road Scholar Private Group Charters Road Scholar educational adventures are created by Elderhostel, the not-for-profit world leader in educational travel since 1975. Enroll 20 and we’ll waive the cost for one more! Greetings! Explore the World I’m Frania Monarski, Road Scholar’s Private Group With Your Group Charter Expert. I’ve helped hundreds of groups plan Road Scholar learning adventures all over the United & Save! States and around the world. Enroll 20 and We’ll Waive I’m here to make planning a Road Scholar adventure the Cost for One More for your group hassle-free. I handle all the details — helping with the marketing, providing your members Share your love of learning by with a special toll-free number to enroll, collecting all enrolling 20 participants on your the payments, sending out the preparatory materials, private group charter, and we’ll and following up with the evaluations at the conclusion waive the program cost for your 21st of the program. I’ll do the work, you take the credit. participant. Or, once you enroll 20, you can choose to receive a 5 percent I’ve put together a list of some our most popular give-back for your organization in programs for you to choose from. Or check out our full lieu of a free place. catalog online at www.roadscholar.org. When you’re ready to get started, just let me know. Have questions? Call (877) 209-4634, or e-mail me at [email protected]. -

Dear Parents and Carers, We Will Miss Seeing Your Child and Working With

Dear Parents and Carers, We will miss seeing your child and working with them. We have provided an overview of the main learning that we had planned to teach this week. We have provided a series of activities that your child can complete at home. There is also a list of websites emailed to all parents/carers that will support home learning e.g. Twinkl, Phonics Play. There will be exercise books available from the office for the children to complete their work in. We understand this is a challenging time so there is no expectation for all set work to be completed. Best wishes, we hope to see you soon. Weekly updates will follow. From The Year 2 Team. Maths Week 1 This week the learning focus is telling the time. In Year 2 the expectation is children can confidently tell the time to o’clock, half past, quarter past and quarter to. Some children will also be able to tell the time to the nearest 5 minutes, e.g. 25 minutes past 8. English / Geography Week 1 The children have been learning about where chocolate can grow and have been focusing on learning about the country Brazil. This week the children will be preparing a project on Brazil. The project can be presented in a variety of formats, e.g. posters, fact file and powerpoints. Within the project the children should be comparing different human and physical features between England and Brazil. Phonics https://www.phonicsplay.co.uk/ Science Week 1 This week we are investigating how we can change the shape of different objects by either pushing, pulling, twisting and stretching. -

SOUTH SIDE STORY All the World’S a Stage

SOUTH SIDE STORY All The World’s A Stage WORLD CRUISE 2023 SYDNEY TO FORT LAUDERDALE | 09 JAN – 28 MAY 2023 ALL THE WORLD’S A STAGE From the South Seas to deep inside the Amazon, join this inspiring epic where you’re both spectator and storyteller. Set off on an exotic voyage to some of the world’s most unique and remote places, for a legendary tale that weaves together a kaleidoscope of sights, sounds and stories. You’ll be treated to inspiring performances, events and celebrations along the way, ho- sted by the extraordinary people you’ll meet at each destination. A new way to see the world, South Side Story is destined to become an instant classic. 2 3 THE WORLD IS AT YOUR DOOR Start your seamless World Cruise journey as soon as you leave your doorstep! Let us take care of all the details, so you can travel in style: a private executive transfer from your home to your closest airport, VIP meet and greet and private assistance, business class lounge access, exclusive fast-track for check-in, boarding and arrival as well as a personalised flight journey. Enjoy a superior flight experience from selected US and UK gateways to Sydney, Australia. Experience a new level of comfort in Qantas Business Class with more space to relax and a dedicated cabin. World Cruise passengers will taste the freshest seasonal ingredients and enjoy Australian hospitality in-flight, presented by Qantas Airways in partnership with Silversea. Upon arrival in Sydney, the experience continues, as we take you straight to Silver Shadow where your butler will await for you. -

Chapter Two Where

Chapter Two Where The actors’ three spaces / In the beginning was the circle / Actors, acrobats and charlatans / From open-air to enclosed space, from selling wares to selling performances / The mountebanks’ hut / The bare stage / The first theatres / The ac- tors’ theatre and the spectators’ theatre / The first theatres in France, Spain, England, Italy, India, Japan, China, United States, Latin America / The invention of the Italian-style theatre, or theatre for the spectator / The first theatres in Italy / La Scala in Milan / Typical elements of the Italian-style theatre: stalls, boxes, galleries, lights, curtain, dressing rooms and foyer / Applause, flowers and whistles / Theatres and exorbitant spectacles / A theatre not made of stones and bricks. 1. Bouvard and Pécuchet fantasise PÉCUCHET – And yet theatre has survived every social, about the actors’ small homes economic and technological earthquake of the past hun- dred years. BOUVARD – Audiences desert a play and the theatre BOUVARD – Perhaps because, sometimes, a performance company goes bankrupt. A government minister signs a has the power to reveal a truth that cannot be revealed by decree and ten theatres close down. All it takes is an eco- reality. nomic crisis, a new fashion or a technological discovery PÉCUCHET – Do you think that’s the reason why one and lots of actors find themselves unemployed. generation after another of actors has abandoned the ii 1 Chapter Two. Where 89 1. Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, Italy: the view from the royal box. Founded in 1737, the San Carlo is the oldest opera theatre still in operation. Destroyed by fire in 1816, it was re- built in a single year and expanded to 2,500 seats. -

Competition Jury

MATTIA OMETTO | Italy President of the Jury The winner of a vast array of awards both in Europe and the United States, Ometto quickly established himself as an artist whose gifts hark back to the Golden Age of classical piano performance, gifts that reflect an artistry that is formed in equal parts by his Venetian background, the influence of his studies in Paris with the legendary Aldo Ciccolini, and in Palm Springs with the American virtuoso Earl Wild. Ometto performs regularly in Europe and the United States. Following his recital debut in Paris at the Théatre du Rond Point des Champs Elysées and in New York City at Carnegie Hall, he appeared both in recital and as soloist with orchestra in New York (Carnegie Hall, Bargemusic), New Jersey, Des Moines (Sheslow Auditorium), Boston (Bradley Hall), Venice (Gran Teatro la Fenice), Berlin, in Los Angeles with the Lyric Symphony orchestra, in Ankara (Turkey) with Academic Baskent Orchestra, in Vidin (Bulgaria) with the Vidin State Philharmonic Orchestra, and in Padua (Italy) with the Orchestra di Padova e del Veneto. Ometto has also worked with renowned conductors such as Luigi Piovano, Maurizio Dini Ciacci, Charles Gambetta and Ertug Korkmaz, just to name a few. Broadcasts of Ometto’s performances and interviews have been featured on numerous radio stations, such as BBC London, Kulturradio Berlin, France Musique, Rai International, Radiotre, Raitrade, Radio della Svizzera Italiana, Radioclassica, Radio Romania, Iowa State Radio, Kanal B Ankara, and WGBH Boston. His discography comprises the critically acclaimed live recording of Poulenc’s Concerto for two pianos and Orchestra (Leonora Armellini, OPV, Luigi Piovano - Brilliant Classics), Johannes Brahms’ complete music for two pianos again with Leonora Armellini (Da Vinci) and the World Premiere Recording of the complete music for two pianos and piano four-hands by Reynaldo Hahn with the legendary pianist and Liszt scholar Leslie Howard (Melba Recordings, 2 CDs). -

Teatro 4 / Play PDF - Descargar, Leer

Teatro 4 / Play PDF - Descargar, Leer DESCARGAR LEER ENGLISH VERSION DOWNLOAD READ Descripción Colee, depieias escogidas, and Tesoro del teatro españ. v. 5, p. 291. 287 ; Bibhot. de autores esjiañ. ; and Ochoa, E. de, Tesoro teatro españ. v. 1, p. 200. 4, p. 105. Amorous bigot. 85 pp. Shadwell, T., Works, v. 4, p. 217. Amorous old-woman. DutTet, T. 1674, Amorous prince. 82 pp. Behn, Mrs. A., Plays, v. 4, p. 257. Among his best received plays are Los puros (The Bold), a brash criticism of demagogues, and along the same lines of national themes and criticism, Los juga- dores (The Players), dealing with large newspaper companies. WORKS: Ensayo N 4 (Play N 4) (Teatro El Gal- pon, 1953) (Pirandellian style). Los puros (Teatro El. FOR M-ID CARD HOLDERS. The PICCOLO TEATRO 2017-2018 SEASON. The Piccolo Teatro offers to all M-Id cardholders a reserved playbill of shows with special rates (see inside every title contents the performance language of the play and if it is also surtitled in other languages). HOW TO CHOOSE AND BUY YOUR. Mafi Metlo Show - La Elko - New play at Teatro Verdun #Mafi_Metlo_Show #La_Elko a new show at Teatro Verdun Comedy Theater Written and directed by Nasser Fakih With: Adel Karam Roula Chamieh Haim Halawi Abbas Chahine Weekly Shows For reservations: 01.800003. Donde Esta Dios? is a play on racism in today's Cuba written by one of Cuba's few serious black actresses, Flor Amalia Lugo. It is performed by the Teatro Negro, a theatre group Flor directs in Havana. -

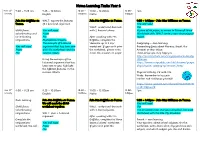

Home Learning Tasks Year 6

Home Learning Tasks Year 6 Mon 18th 10:30 – 12:00- 9.00 – 9.25 am 9.25 – 10.30am 11:00 – 12:00pm 1pm January English 11:00am Maths 1:00pm Join Mrs Griffiths on WALT: explore the features Join Mrs Griffiths on Teams. 1:00 – 1:45pm - Join Miss Williams on Teams. Teams. of a balanced argument You will need: WALT: understand decimals Pen SPAG focus – You will need: with 2 decimal places A piece of A4 paper, or access to Microsoft Word subordinating and Paper Worksheet with ‘WALT: write a non-chronological co-ordinating Pen After speaking with Mrs report.’ conjunctions Highlighters/crayons Griffiths, complete the The example of balanced ‘decimals up to 2 d.p.’ Geography – own learning You will need: argument that has been sent worksheet. If you can’t print Researching facts about Manaus, Brazil, the Paper with the worksheets and the the worksheet, please write Amazon or their tribes. Pen success criteria down the answers on paper. These webpages may help you: http://academickids.com/encyclopedia/index.php Using the example of the /Manaus balanced argument that has https://www.natgeokids.com/uk/discover/geogra been sent to you, highlight phy/physical-geography/amazon-facts/ the different features on the success criteria. Physical Activity: PE with Joe Wicks. Remember to try your hardest and challenge yourself! https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCAxW1XT0i EJo0TYlRfn6rYQ Tues 19th 9.00 – 9.25 am 9.25 – 10.30am 10:30 – 11:00 – 12:00pm 12:00- 1pm January English 11:00am Maths 1:00pm Own learning Join Mrs Griffiths on Teams. -

Booking.Com Reveals Where Travelers Are Staying During the 2016 Summer Games

July 14, 2016 Booking.com Reveals Where Travelers are Staying During the 2016 Summer Games NEW YORK, July 14, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- This August the athletic calendar's biggest event takes place in fabulous Rio de Janeiro. The vibrant city will play host to world-class athletic competitions in 32 venues across the city. Booking.com, the global leader in connecting travelers with the widest choice of incredible places to stay, today reveals the most popular districts to stay in Rio during the 2016 Summer Games. The Copacabana district, which houses the volleyball arena, and windsurfing space 'Marina da Glória' among others, is the most-booked area in Rio de Janeiro to date followed by the Centro, Santa Teresa, Barra da Tijuca and Ipanema districts.* While Booking.com has seen travelers from Brazil, United States and Argentina book the most frequently, for those who have not booked yet there is limited availability. As of today, only 17% of accommodations on Booking.com are available during the event. For travelers who are heading to the games and want to extend their trip the booking engine, which offers more places to stay than any other travel brand in the world, has pulled together six ideal hotspots across Brazil according to guest feedback. Whether you prefer sipping the national cocktail Caipirinha by the pool or marvelling at the Amazon River, these recommendations will help travelers discover the real 'Espiritu de Brasil' (Spirit of Brazil). 1. Head to Rio de Janeiro (Estado do Rio de Janeiro) to soak up beach life, scenery and sightseeing. Casa Amarelo Boutique Hotel This chic hotel is the perfect setting for a relaxed Brazilian experience. -

Amazoncruisingthe

AmazonCRUISINGTHE On day two of his traditional Amazon River and Negro River nature cruise, Carlos Probst takes guests out for some early afternoon piranha fishing. Probst makes the ship’s captain guide the 70-foot shallow-hull riverboat toward the lush tree-canopied shore, so that passengers can depart on canoes to do battle with the notoriously ferocious fish. The tackle is simple: bamboo rod, fishing line and a hook. For bait, Probst prefers raw meat, but anything will do for this not-so-finicky scavenger. He deadpans if anyone is willing to spare a finger. The joke invariably gets laughs from a crowd of around 16 who have already had a full day of activi- ties. Even before breakfast, passengers were treated to a dramatic Amazon River basin sunrise and a 20 BOSS ᔢ SPRING 2 0 1 0 bird-watching canoe trip to see such in pampered, five-star style. The winged creatures as egret, macaw or Premium, which features spacious cabins hoatzin, pheasant-sized tropical birds with cozy beds and hot showers, in 2007 known for their spiky head crests. hosted German President Horst Kohler After a meal and some slow cruising, and several German ministers. Probst passengers go on land for a guided tour actually counts several celebrities among of the rain forest followed by a visit to a his clientele, but he’s wary to name drop. small coastal village whose inhabitants Probst says what draws people of subsist off the river and forest. Then it’s all sorts to the Amazon is the region’s “Here we have back on the boat for lunch and more rich symphony of life.