The Struggle of the LGBTIQ* Community to Achieve Visibility On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television

UC Santa Barbara Global Societies Journal Title The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13s698mx Journal Global Societies Journal, 1(1) Author Elouardaoui, Ouidyane Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television | 100 The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? By: Ouidyane Elouardaoui ABSTRACT Arab media has experienced a radical shift starting in the 1990s with the emergence of a wide range of private satellite TV channels. These new TV channels, such as MBC (Middle East Broadcasting Center) and Aljazeera have rapidly become the leading Arab channels in the realms of entertainment and news broadcasting. These transnational channels are believed by many scholars to have challenged the traditional approach of their government–owned counterparts. Alternatively, other scholars argue that despite the easy flow of capital and images in present Arab television, having access to trustworthy information still poses a challenge due to the governments’ grip on the production and distribution of visual media. This paper brings together these contrasting perspectives, arguing that despite the unifying role of satellite Arab TV channels, in which national challenges are cast as common regional worries, democratization and social development have suffered. One primary factor is the presence of relationships forged between television broadcasters with influential government figures nationally and regionally within the Arab world. -

2020 SFCG Conflict Analysis Report

Search for Common Ground’s “Conflict Analysis and Power Dynamics – Lebanon” Study Implemented in Akkar, the North, Mount Lebanon, Central and West Bekaa, Baalbeck-Hermel and Beirut RESEARCH REPORT JULY 2020 Research Team: Bérangère Pineau Soukkarieh, Team Leader Melike Karlidag, Technical Analyst Lizzy Galliver, Researcher Contact: Ramy Barhouche Mohammad Hashisho Project Manager Consortium Monitoring & Reporting Officer Search for Common Ground Search for Common Ground [email protected] [email protected] Research Report | Conflict Analysis and Power Dynamics – Lebanon Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abbreviations 3 List of tables and figures 4 Executive Summary 5 1. Background Information 9 Introduction 9 2. Methodology 11 Research Objectives 11 Data Collection and Analysis 11 Limitations and Challenges 17 3. Findings 19 Structures 19 Actors and Key Stakeholders 35 Dynamics 60 4. Conclusions 75 5. Recommendations 77 6. Appendices 83 Annex 1: Area Profiles 83 Annex 2: Additional Tables on Survey Sample 84 Annex 3: Baseline Indicators 86 Annex 4: Documents Consulted 88 Annex 5: Data Collection Tools 89 Annex 6: Evaluation Terms of Reference (ToR) 109 Annex 7: Training Curriculum 114 Search for Common Ground | LEBANON 2 Research Report | Conflict Analysis and Power Dynamics – Lebanon Acknowledgements The consultant team would like to thank Search for Common Ground’s staff for their valuable feedBack on the design of the study and the report’s content. The authors of this report would also like to thank all key informants who took the time to inform this assessment. Special thanks are owed to all the community memBers who agreed to participate and inform the study with their insights. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

Journalists' Pact

Journalists’ Pact for Strengthening Civil Peace in in Lebanon The analysis and recommendations regarding the policies indicated in this report do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). This document has been printed with the support of the European Union and does not reflect in any way the opinion and views of the European Union. 2 Introduction In the context of its work within the media component, the UNDP “Strengthening Civil Peace in Lebanon” project, funded by the European Union, gathered the decision mak- ers in the print and audio-visual media outlets and websites, from various political affiliations, to discuss the role of the media in the promotion of civil peace and on how to employ this role at both the local and national levels. The project has been organiz- ing, since 2007, workshops for the capacity building of media professionals and for the provision of analytical means that would render their media products more objective and accurate. Accordingly, a meeting has been held between the UN Resident Coordinator Mr. Robert Watkins and the Minister of Information Mr. Walid Daouk to discuss the work related to the consolidation of the role of the media in strengthening civil peace. Minister of Information showed great interest in the subject. Within this framework, the project decided to work on the elaboration of the “Journal- ists’ Pact for Strengthening Civil Peace in Lebanon” so as to highlight the importance of the media and its role in strengthening civil peace in Lebanon. It is worth noting that the UNDP “Strengthening Civil Peace in Lebanon” project took rather an unconventional approach in selecting the editors-in-chief adopting a long- term participatory approach, ensuring their full involvement and engagement in the process. -

Al-Jazeera Through Today

“The opinion, and the other opinion” Sustaining a Free Press in the Middle East Kahlil Byrd and Theresse Kawarabayashi MIT’s Media in Transition 3 May 2-4, 2003 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND AND HISTORY .............................................................................. 3 The Emir and Qatar, ................................................................................................... 3 Al-Jazeera Through Today ......................................................................................... 5 Critics of Al-Jazeera ................................................................................................... 6 BUSINESS MODEL ..................................................................................................... 7 Value Proposition....................................................................................................... 7 Market Segment.......................................................................................................... 8 Cost Structure and Profit Potential............................................................................ 9 Competitive Strategy ................................................................................................ 11 THE GLOBALIZATION OF AL-JAZEERA.......................................................... 13 CHALLENGES AL-JAZEERA FACES IN SUSTAINING ITS SUCCESS ........ 15 AL-JAZEERA’S NEXT MOVES............................................................................. -

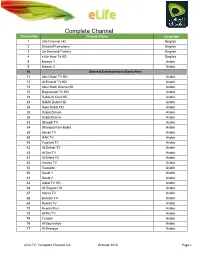

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Project of Statistical Data Collection on Film and Audiovisual Markets in 9 Mediterranean Countries

Film and audiovisual data collection project EU funded Programme FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL DATA COLLECTION PROJECT PROJECT TO COLLECT DATA ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL PROJECT OF STATISTICAL DATA COLLECTION ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL MARKETS IN 9 MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Country profile: 3. LEBANON EUROMED AUDIOVISUAL III / CDSU in collaboration with the EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Dr. Sahar Ali, Media Expert, CDSU Euromed Audiovisual III Under the supervision of Dr. André Lange, Head of the Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe) Tunis, 27th February 2013 Film and audiovisual data collection project Disclaimer “The present publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. The capacity development support unit of Euromed Audiovisual III programme is alone responsible for the content of this publication which can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, or of the European Audiovisual Observatory or of the Council of Europe of which it is part.” The report is available on the website of the programme: www.euromedaudiovisual.net Film and audiovisual data collection project NATIONAL AUDIOVISUAL LANDSCAPE IN NINE PARTNER COUNTRIES LEBANON 1. BASIC DATA ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Institutions................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Landmarks ............................................................................................................................... -

Communication Interventions Supporting Positive Civic Action in Lebanon

Helpdesk Report Communication interventions supporting positive civic action in Lebanon Dylan O’Driscoll University of Manchester 05 March 2018 Questions What communications or programmatic efforts are available to support positive civic action programmes in Lebanon? What is the media landscape for communication interventions? Contents 1. Overview 2. Media and Tensions/Conflict resolution 3. Communication Initiatives 4. Media in Lebanon 5. Social Media in Lebanon 6. References The K4D helpdesk service provides brief summaries of current research, evidence, and lessons learned. Helpdesk reports are not rigorous or systematic reviews; they are intended to provide an introduction to the most important evidence related to a research question. They draw on a rapid desk-based review of published literature and consultation with subject specialists. Helpdesk reports are commissioned by the UK Department for International Development and other Government departments, but the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of DFID, the UK Government, K4D or any other contributing organisation. For further information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Overview Lebanon witnessed a vicious civil war between 1975 and 1990 in which tens of thousands of civilians were killed, injured, displaced, disappeared, or harmed in the violence. The Ta’if Agreement ended the war; however, by dividing power between the three main confessions it entrenched divides within society. Moreover, by creating an amnesty for crimes during the civil war, -

1-U3753-WHS-Prog-Channel-FIBE

CHANNEL LISTING FIBE TV CURRENT AS OF JANUARY 15, 2015. $ 95/MO.1 CTV NEWS CHANNEL.............................501 NBC HD ........................................................ 1220 TSN1 ................................................................ 400 IN A BUNDLE CTV NEWS CHANNEL HD ..................1501 NTV - ST. JOHN’S ......................................212 TSN1 HD .......................................................1400 GOOD FROM 41 CTV TWO ......................................................202 O TSN RADIO 1050 .......................................977 A CTV TWO HD ............................................ 1202 OMNI.1 - TORONTO ................................206 TSN RADIO 1290 WINNIPEG ..............979 ABC - EAST ................................................... 221 E OMNI.1 HD - TORONTO ......................1206 TSN RADIO 990 MONTREAL ............ 980 ABC HD - EAST ..........................................1221 E! .........................................................................621 OMNI.2 - TORONTO ............................... 207 TSN3 ........................................................ VARIES ABORIGINAL VOICES RADIO ............946 E! HD ................................................................1621 OMNI.2 HD - TORONTO ......................1207 TSN3 HD ................................................ VARIES AMI-AUDIO ....................................................49 ÉSPACE MUSIQUE ................................... 975 ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE TSN4 ....................................................... -

Lebanon's Media Sectarianism

Lebanon’s Media Sectarianism By Paul Cochrane May, 2007. Politics have become so divisive in Lebanon, on the streets and on TV screens, that the national media council chief urged the media in January to curb "tense rhetoric" that could instigate violence among the country's religious sects.1 Lebanon was plunged into a power struggle on December 1, 2006 when the Hizbullah-led opposition, consisting of Shiite Muslim parties and Michel Aoun's majority Christian party, camped out in downtown Beirut to call for the overthrow of Prime Minister Fouad 2 Siniora's pro-US government. Rallying around the flag: The media's divisions were apparent at the second anniversary of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri's assassination on February 14th 2007, with opposition channels giving minimal coverage of the event in Beirut's Martyrs' Square. Photograph by Paul Cochrane. 1 “Media council chief cites perils of 'tense rhetoric,'” The Daily Star, January 30, 2007 2 As of going to press, the opposition is still camped out in Martyrs’ Square. Feature Article 1 Arab Media & Society (May, 2007) Paul Cochrane The situation reached a climax in January following two separate clashes between pro- and anti-government supporters that left seven dead and 190 wounded. Purchases of automatic weapons have also reportedly risen, from $100 to $1000 for an AK47, and with the government seizing a cache of arms intended for Hizbullah in March, concerns were raised that the sectarianism of Lebanon's 15-year civil war, which ended in 1990, could return. The Lebanese media has played its role in the current crisis, with the National Media Council president, Abdel-Hadi Mahfouz, blaming the media for stoking sectarianism and engaging in political insults. -

Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sharp, Deen Shariff Doctoral Thesis — Published Version Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon Provided in Cooperation with: The Bichler & Nitzan Archives Suggested Citation: Sharp, Deen Shariff (2018) : Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon, Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences, City University of New York, New York, NY, http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/593/ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/195088 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon C o r p o r a t e U r b a n i z a t i o n By Deen Shariff Sharp, 2018 i City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Graduate Center 9-2018 Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon Deen S.