Preface to the Scottish Diaspora Tapestry Scotland's Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constantia, St

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY REFERENCE CYCLOPEDIA of BIBLICAL, THEOLOGICAL and ECCLESIASTICAL LITERATURE Constantia, St. - Czechowitzky, Martin by James Strong & John McClintock To the Students of the Words, Works and Ways of God: Welcome to the AGES Digital Library. We trust your experience with this and other volumes in the Library fulfills our motto and vision which is our commitment to you: MAKING THE WORDS OF THE WISE AVAILABLE TO ALL — INEXPENSIVELY. AGES Software Rio, WI USA Version 1.0 © 2000 2 Constantia, Saint a martyr at Nuceria, under Nero, is commemorated September 19 in Usuard's Martyrology. Constantianus, Saint abbot and recluse, was born in Auvergne in the beginning of the 6th century, and died A.D. 570. He is commemorated December 1 (Le Cointe, Ann. Eccl. Fran. 1:398, 863). Constantin, Boniface a French theologian, belonging to the Jesuit order, was born at Magni (near Geneva) in 1590, was professor of rhetoric and philosophy at Lyons, and died at Vienne, Dauphine, November 8, 1651. He wrote, Vie de Cl. de Granger Eveque et Prince dae Geneve (Lyons, 1640): — Historiae Sanctorum Angelorum Epitome (ibid. 1652), a singular work upon the history of angels. He also-wrote some other works on theology. See Hoefer, Nouv. Biog. Generale, s.v.; Jocher, Allgemeines Gelehrten- Lexikon, s.v. Constantine (or Constantius), Saint is represented as a bishop, whose deposition occurred at Gap, in France. He is commemorated April 12 (Gallia Christiana 1:454). SEE CONSTANTINIUS. Constantine Of Constantinople deacon and chartophylax of the metropolitan Church of Constantinople, lived before the 8th century. There is a MS. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

GTCS National Lecture Glasgow 2014 CEO, David Grevemberg, Considers the Legacy of the Commonwealth Games

Council Election Dr Tony Pollard Senior Benchmarking Ensure you make Commemorating Exploring a crucial element an informed choice World War One of Curriculum for Excellence February/March 2014 Issue 53 For the teaching profession, by the teaching profession Professional Update is coming Get yourself ready for August 2014 Professional Learning What it means to you and your colleagues GTCS National Lecture Glasgow 2014 CEO, David Grevemberg, considers the legacy of the Commonwealth Games Teaching Scotland . 3 Are your details up to date? Check on MyGTCS www.teachingscotland.org.uk CONTENTS Teaching Scotland Magazine ~ February/March 2014 EXERCISE YOUR RIGHT TO VOTE David Drever, Convener, GTC Scotland PAGE 14 Contacts GTC Scotland www.gtcs.org.uk [email protected] Customer services: 0131 314 6080 Main switchboard: 0131 314 6000 32 History lessons With The Great Tapestry of Scotland 16 Let the Games begin 36 Professional Learning David Grevemberg, CEO Glasgow 2014, Teacher quality is at the heart vows to empower our young people of the new Professional Update 22 Make your mark 40 Reflective practice Information on candidates for the Dr Bróna Murphy adopts a more Council Election and FE vacancy dialogic approach to reflection 26 Lest we forget 42 How do you measure up? Marking the centenary of the A look at the new Senior Phase start of the First World War Benchmarking Tool 30 Unlocking treasure troves 44 Icelandic adventures Archive experts and teachers are How a visit to Iceland sparked Cherry Please scan this graphic adapting material for today’s lessons Hopton’s love of co-operative learning with your mobile QR code app to go straight 34 Creative Conversations 50 The Last Word to our website Creative Learning Network initiative Dee Matthew, Education Co-ordinator is helping educators share expertise for Show Racism the Red Card “Teachers teach respect and responsibility, discipline, determination, excellence and courage – all really important values” David Grevemberg, CEO, Glasgow 2014, page 16 4 . -

Embroiderers Wanted for Epic Battle Tapestry

Bonnie Prince Charlie’s crushing defeat at Culloden is one of the best-known episodes in Scottish history – but now the story of his greatest victory is to be told in Scotland’s very own version of the Bayeux Tapestry. Original photograph by Gillian Hart. David Lee and Gaynor Allen explain how the EMBROIDERERS project came about and the organisers’ appeal for WANTED FOR EPIC East Lothian volunteer embroiderers. BATTLE TAPESTRY he Bayeux Tapestry is one of the for the huge tapestry, a key part of an armies. The Battle Trust is especially keen greatest and best-known historical ambitious £15m campaign to build a to hear from individuals and groups artworks. Now an 80 metre-long living history visitor centre in around Dunbar and Haddington who are T tapestry commemorating Bonnie Prestonpans – and to protect the willing to embroider the panels relating Prince Charlie's glorious campaign, up to battlefield site from development. to John Cope’s route in the days before an including his victory at the Battle of Although over half the panels have the battle. Prestonpans in September 1745, is taking already been allocated, volunteer Prestonpans was the first battle of the shape – and will find a permanent home embroiderers are still being sought in second major Jacobite rebellion, which in East Lothian. communities along the route of both began when Charles Edward Stuart came The project is being co-ordinated by to Scotland to raise troops and reclaim the Battle of Prestonpans 1745 Heritage the crown for his deposed father James Trust as a way of portraying the youthful from George II. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

Our Vision for Victory

The Battle of Prestonpans (1745) Heritage Trust presents OUR VISION FOR VICTORY A prospectus for the future of one of Scotland’s most significant battlefields and its cultural legacy, and a permanent home for The Prestonpans Tapestry. www.visionforvictory1745.org Introduction In the early morning of 21st September 1745, the Jacobite Army of Prince Since 2006 the Battle of Prestonpans (1745) Heritage Trust Charles Edward Stuart swept to victory across the stubble fields to the east has worked to protect, promote and continue that legacy. Through of the coastal village of Prestonpans. Their success was swift and complete, interpretation, education, events and exhibitions, the Trust has carried the and for the victors it seemed nothing was now impossible. The Battle of story of the battle to hundreds of thousands of people, whilst supporting Prestonpans was the first battle of the last Jacobite uprising, and the most ongoing research and evaluation of the battlefield and campaigning for comprehensive victory the cause of the exiled Stuarts had ever achieved. It its protection. In 2010 it launched the Prestonpans Tapestry, triggering a was all the more astonishing for its unlikelihood. renaissance of narrative embroidery in Scotland and beyond. So shocking was the outcome that British society had an instant This document presents the Trust’s ambition for the future: the creation fascination with the events at Prestonpans, a need to understand what had of a unique visitor attraction at Prestonpans Battlefield, building on the happened and to commemorate it. The names of those who faced each momentum of our past to secure an exciting and sustainable future. -

The Great Tapestry of Scotland Free

FREE THE GREAT TAPESTRY OF SCOTLAND PDF Alistair Moffat,Andrew Crummy | 368 pages | 01 Oct 2014 | Birlinn General | 9781780271606 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Scottish Tapestry The Prestonpans Tapestryor in full the Battle of Prestonpans Tapestryis a large embroidery created — and normally situated in — PrestonpansEast Lothian, Scotland. The design, size and style were The Great Tapestry of Scotland by the Bayeux Tapestry. The Tapestry is, like the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered cloth, rather than a true woven tapestry. More than two hundred embroiderers created the work over a two-year period; more than half these reside in Scotland from the places where Bonnie Prince Charlie marched to his victory. The embroiderers were led by Dorie Wilkie. The completed work was unveiled to a private gathering of of the embroiderers and their friends on 26 Julyat The Greenhills near Cockenzie Power Stationwhich is on the edge of the Prestonpans battlefield itself. Since its creation, the Tapestry has since travelled around the Highlands and Lowlands, and to England and France, attracting overvisitors in its first two years. In September and October it was exhibited in Bayeux by invitation of the tapestry that was its inspiration. The Battle of Prestonpans [] Heritage Trust expects to be able to find a permanent home within the next five years [ when? Designed by historian and co-chairman Alistair Moffat and artist Andrew Crummy, with contributions from approximately stitchers from across Scotland, it depicts the history of Scotland from prehistoric times until the present day. The longest tapestry in the world at that time, it was unveiled at the Scottish Parliament on 3 September where it hung for 3 weeks. -

SPCB(2017)Paper 46 18 May 2017

SPCB(2017)Paper 46 18 May 2017 MAJOR EVENTS AND EXHIBITIONS PROGRAMME 2017/18: THE PRESTONPANS TAPESTRY Executive Summary 1. This Paper seeks the SPCB’s approval for a proposal to exhibit The Prestonpans Tapestry in the Parliament’s Main Hall as part of the Major Events and Exhibitions Programme for 2017/18. 2. The Tapestry is owned by the Battle of Prestonpans (1745) Heritage Trust who approached Iain Gray MSP to explore the possibility of a public exhibition. 3. If approved, the exhibition would be on public display in the Parliament’s Main Hall from Wednesday 21 June to Thursday 20 July 2017 with a Presiding Officer hosted preview reception on Tuesday 20 June. Background 4. The Prestonpans Tapestry, completed in 2010, is one of the nation’s most significant and ambitious community arts projects. It depicts the story of Charles Edward Stuart’s opening campaign to regain the British throne for the exiled Stuart dynasty in 1745. It covers the events from Charles’ departure from Rome for France, through his summer campaign in Scotland and the victory at Prestonpans, culminating in his departure from Edinburgh. It also follows the marches of the redcoat forces of Sir John Cope. 5. The Tapestry and was inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry. Over 200 volunteers from across Scotland took more than 25,000 hours to create the panels, working to designs drawn by artist Andrew Crummy. Crummy went on to create the artwork for the Great Tapestry of Scotland (hosted by the Parliament in 2013 and 2014) and the Scottish Diaspora Tapestry. -

Making Sense of the Bayeux Tapestry Anna C

Introduction: making sense of the Bayeux Tapestry Anna C. Henderson There is no university with a department of Bayeux Tapestry studies. Instead scholars write about the Tapestry from within history or art history departments, or as specialists in literature or archaeology. The Tapestry is likely to be only one element within our domain of scholarly interests. It may or may not be crucial to our day jobs. But as an interdisciplinary object the Tapestry is able to command a different range of significance for each of us. As we celebrate Gale Owen-Crocker’s long, energetic and collabora- tive career, I want to use this introduction as an exercise in thinking about the ways in which scholars and their subjects are brought together. In his influential book and television series, Ways of Seeing (1972),1 John Berger argues that, ‘We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice. As a result of this act, what we see is brought within our reach’. Looking, according to this interpretation, is individuated, active and results in an act of composition, since what we choose to see will form our world view. He goes on to make the point that in the act of grasping our own powers of perception we become aware that others’ viewpoints may differ from our own. Dialogue is a matter of attempting to explain and bridge that gap. Maggie Humm talks in similar terms about a form of selective listening: Lectures only move us in relation to our own academic memories and academic desires and can then help us structure a sense of our academic identity. -

BL1609 September 2016.Psd

Blackwork Journey Blog, September 2016 August has been a really hectic month, with my son and his wife moving to San Francisco with baby James and taking up a new life and career as the Principal horn player with the San Francisco Opera. We have been to San Francisco several times and will be looking forward to more journeys across the 'Pond' in 2017 and to visiting the splendid building which houses the Opera Company. I may even get the chance to meet some of my Facebook members who live in the San Francisco area! 'Sublime Stitches' - the November project As usual in a British summer, we have had quite a lot of rain which is the best excuse ever for either designing new patterns or working on my November project, 'Sublime Stitches'. One of the alphabets in 'Sublime Stitches' was taken from an old linen sampler in my collection, which whilst small, badly worn and faded, was perfectly executed in four-sided stitch.! Like 'Save the Stitches' it will be a large and rather intricate piece of work which I hope will challenge and inspire you to new adventures in stitching. The historical aspects of the embroidery and the research involved really appeals to my creative side and where possible I have included information about the background of the stitches and patterns. I have also included traditional embroidery stitches which are often overlooked in counted thread embroidery but can add texture and interest. This sampler is a very personal piece and includes the stitches and patterns that I especially enjoy working. -

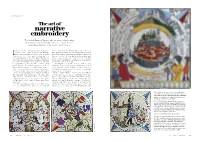

Narrative Embroidery , Which She Panel Demonstrates the Use of Stem and the Books, Scottish Diaspora

COMMUNITY The art of narrati ve embroi dery The Scottish Diaspora Tapestry tells the story of Scots making their way in the world throughout history – and its creation united the endeavours of stitchers across 31 nations n recent years the small town of Prestonpans, which community project’ the Diaspora tells the tales of the Scots lies on the Firth of Forth to the east of Edinburgh, who dispersed around the globe, building new lives, often Ihas become synonymous with the creation of epic thousands of miles away from their homes. Wherever in embroideries. The first major embroidery, the the world they live, the Scots and their descendants today Prestonpans Tapestry , emulated the Bayeux Tapestry and retain a sense of pride and connection to their Scottish was worked in a restricted range of stitches and limited heritage, and their skills have often had a profound impact colour palette. Worked by around 200 stitchers from on the areas where they settled. the communities that Bonnie Prince Charlie’s army Celebrating those accomplishments and influences, the passed through, the resulting 104 panels, each one embroidered panels of the Diaspora Tapestry were stitched metre wide and almost half a metre deep, trace the in countries from Russia to Brazil and from Ethiopia to steps of the Prince from exile in France, culminating in Antarctica, making them as widely travelled as the people the Battle of Prestonpans, a resounding Jacobite victory. whose stories they document. Another even bigger project, The Tapestry of Scotland , Everyone involved with the creation of the epic artworks also emanated from Prestonpans, with more than is aware that they are in fact embroideries, but they 1,000 volunteer stitchers from all over Scotland reference the world’s most famous embroidery, the Bayeux completing some 160 panels, each one metre square. -

Our Stories Case Studies

Ackton and North Featherstone Community Forum – Our School .......................................1 Adult Learning Project, Edinburgh – Women in Stone .........................................................3 Amersham Museum Ltd – Metroland: the Birth of Amersham-on-the-Hill ..........................5 Apsley Paper Trail - The Paper Valley .................................................................................7 ASSIST – Then, Now, If… .....................................................................................................9 Barrow upon Trent Parish Plan - Barrow on Trent Discovers its past ................................. 11 Beaminster Museum - Our Flax and Hemp Heritage ......................................................... 13 The Beat Project – Capturing Community Heritage in West Malling, Kent ......................... 15 Bedford College of Physical Education Old Students' Association - Bedford Physical Training College Stories ...................................................................................... 17 Bedlingtonshire Development Trust: Bedlington.....Our Heritage...................................... 19 Berneray Historical Society .............................................................................................. 21 Bluebell Railway Trust – A Golden Age of Steam .............................................................. 23 The Bridgend Centre – Bridging the Gap ........................................................................... 25 Brunel Museum: A Tranquil Waterway leading