"Sure It's Foreign Music, but It's Not Foreign to Me" Understanding K-Pop's Popularity in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the Youtuber Zoella

In The Time of the Microcelebrity Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella Jerslev, Anne Published in: International Journal of Communication Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-ND Citation for published version (APA): Jerslev, A. (2016). In The Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5233-5251. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5078/1822 Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 5233–5251 1932–8036/20160005 In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella ANNE JERSLEV University of Copenhagen, Denmark This article discusses the temporal changes in celebrity culture occasioned by the dissemination of digital media, social network sites, and video-sharing platforms, arguing that, in contemporary celebrity culture, different temporalities are connected to the performance of celebrity in different media: a temporality of plenty, of permanent updating related to digital media celebrity; and a temporality of scarcity distinctive of large-scale international film and television celebrities. The article takes issue with the term celebrification and suggests that celebrification on social media platforms works along a temporality of permanent updating, of immediacy and authenticity. Taking UK YouTube vlogger and microcelebrity Zoella as the analytical case, the article points out that microcelebrity strategies are especially connected with the display of accessibility, presence, and intimacy online; moreover, the broadening of processes of celebrification beyond YouTube may put pressure on microcelebrities’ claim to authenticity. Keywords: celebrification, microcelebrity, YouTubers, vlogging, social media, celebrity culture YouTubers are a huge phenomenon online. -

OCTOBER 1960 • • R St Rs (Conthiued Fi.·Om Page 1) Some :Sources in 1959 to 1960 ; Ary Increases for the Business

•.' _, -PERMANENT FILE '•' STATIONARY. ~ ENGfNEERS. ·. '· ... .·. -~· - .. OCTOBER,"1960 • " ~- ~- .,,.,. " J ' • •• r • • '•Ort ~ - r • :• s• "'• Past. -~ .' . --· \! . By NEWELL J. · CA~MAN, Superf isor : ·, io~aL B< Election;,, .·· ·. ;: .c. " , .' SUPElR.V.ISOR TM report-. unfolded ~ below is -~one ::. of .genuine .· accorriplfshmerit : by the Officers and Members toward improvement ·oftoc~l :N·o. 3's - .. REPORTS -~ st~tti:i-e iii: the LabOr Movement and :the community. This same p~dod _has been one of difficulty _·::1\ . :.- ~a~:-:::·-~- ·t· .. _,;·_··;_··· o~/·.:··· a-- ···- e:· < ~_:: ·· a ·ctlle:-=- .l -.-i·. · ;FiNANCES: · .. for the--Laj)or ... _. :- .. ·. ~ __1, ...:- .~ ~. '·. /: u t' Movement: As a result of labor legislation, the day-to;.day £:unc :.ye · ~q~·t W:~rt,h~Op' ll , per tions of a. labor union . · · c;ent have been.. tremendously complicated .. This · . .· .. • · . · · report is one in which · -•Income Down ;.... .Protec:- the membership m<~y be· proud because . -tici'n ·.up,·. · · · withoqt .the~r sincere --cooperation and understanding from the maj~.r,:ity tb,e task could not h<~ up-.;-:Resul!:s.Up _ve •• . Mo•~ " t5~·. l'alliid ·: Nov.,• 2~ -.>•_Cost~ '. been·· · so suec~ssfully · acc'oni- ()n the ord~i: ~ of S_up~~vis.or New ,eli. '"J~ . C~rn~a:n.; a_cting unde;, di · . • Members: , Moriey~Safe plished. · · . , r.ectlon' Qf-Ge)l'eralPresidell,t Joseph JhD_elaney~ an'electlori of' ·cott~ctrve aA.fiG~INI;i\iG - . In spite. of the significant'" ad~ · fleers and -D1§tricf Executive ·J.3oard ·.Memb€rs .of Operating . · ··wage: Increases - 'More 'd'itional expenditures of 'the1' Lo giiie$rs :· LCic<U Union ·· N:o: 3 :will b.e li~la .:ne:xtrnonth . -

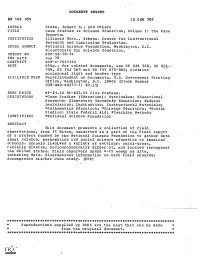

CONTRACT Case Studies in Science Education, Volume I: the Case 658P.; for Related Documents, See SE 026 360, SE 0261 Occasional

DOCUMENT RESUME E6 166 058 SE 026 707 AUTHOR Stake, Robert E.; And Others TITLE Case Studies in Science Education, Volume I: The Case Reports. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Center for Instructional - Research and Curriculum Evaluation. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. Directorate for Science Education. REPORT NO NSF-SE-78-74 PUB DATE Jan 78 CONTRACT NSF-C-7621134 NOTE 658p.; For related documents, see SE 026 360, SE 0261 708, ED 152 565 and ED 153 875-880; Contains occasional light and broken type AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (Stock Number 038-000-00377-1; $7.25) EDRS PRICE MF-$1.16 HC-$35.49 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Case Studies (Education); Curriculum; Educational Research; Elementary Secondail Education; Federal Legislation; Instruction; Instructional Materials; *Mathematics Education; *Science Education; *Social Studies; State Federal Aid; *Teaching Methods" IDENTIFIERS *National Science Foundation ABSTRACT This document presents a collection of field observations, from 11 -sites, submitted as a part of the final report of a project funded by the National Science Foundation to gather data about science, mathematics and social science education in Amerlcad schools. Schools involved a variety of settings: rural-urban, racially diverse, socioeconomically different, and located throughout the United States. Field observers spend 4-15 weeks on site, gathering data. Biographical information on each field observer accompanies his/her case study. (PEB) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can_be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION I. WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN -. -

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present

Article The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present Mohamed Elaskary Department of Arabic Interpretation, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul 17035, South Korea; [email protected]; Tel. +821054312809 Received: 01 October 2018; Accepted: 22 October 2018; Published: 25 October 2018 Abstract: The Korean Wave—otherwise known as Hallyu or Neo-Hallyu—has a particularly strong influence on the Middle East but scholarly attention has not reflected this occurrence. In this article I provide a brief history of Hallyu, noting its mix of cultural and economic characteristics, and then analyse the reception of the phenomenon in the Arab Middle East by considering fan activity on social media platforms. I then conclude by discussing the cultural, political and economic benefits of Hallyu to Korea and indeed the wider world. For the sake of convenience, I will be using the term Hallyu (or Neo-Hallyu) rather than the Korean Wave throughout my paper. Keywords: Hallyu; Korean Wave; K-drama; K-pop; media; Middle East; “Gangnam Style”; Psy; Turkish drama 1. Introduction My first encounter with Korean culture was in 2010 when I was invited to present a paper at a conference on the Korean Wave that was held in Seoul in October 2010. In that presentation, I highlighted that Korean drama had been well received in the Arab world because most Korean drama themes (social, historical and familial) appeal to Arab viewers. In addition, the lack of nudity in these dramas as opposed to that of Western dramas made them more appealing to Arab viewers. The number of research papers and books focused on Hallyu at that time was minimal. -

Early STRATEGY of the MONTH EXTENDING

CORE WORD: Early For Educators, Related Service Providers and Parents STRATEGY OF THE MONTH EXTENDING, EXPANDING AND ELABORATING The AAC strategy of Extending, Expanding and Elaborating focuses on communication partners responding to what students express by providing immediate, (simultaneous) verbal and AAC system modeling based on the student's unique language goals. As an example, students at the single-word level may have a goal to produce two-word utterances and therefore the ‘add a word’ approach could be utilized, (providing modeling by adding a word to the utterance/word produced). Such added words could be targeted as: pronouns, verbs, or descriptors, (for added specificity). Intermediate to advanced communicators would have different, higher-level language goals and targets that are individualized. When using the Extending, Expanding and Elaborating approach, it is suggested that such modeling is carried out in a positive, upbeat tone and with correct grammar and syntax. WAYS WE CAN USE THE WORD SHARE INFORMATION: (e.g., I am early) ASK A QUESTION: (e.g., am I early?) DESCRIBE: (e.g., too early) NEGATE: (e.g., you are not early) ROUTINES AND SCHEDULES Circle: Adults and students can use early to indicate who was early to school during the morning circle time routine. 1 Snack time: Adults can lead students in a discussion about foods and the difference between what type of foods you eat early in the day such as breakfast food (e.g., eggs, toast, yogurt, etc.). PLAY Freeze Dance: Students can play freeze dance and when an adult or student pauses the music, students can point out if anyone stopped dancing too early. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Identity Under Japanese Occupation

1 “BECOMING JAPANESE:” IDENTITY UNDER JAPANESE OCCUPATION GRADES: 9-12 AUTHOR: Katherine Murphy TOPIC/THEME: Japanese Occupation, World War II, Korean Culture, Identity TIME REQUIRED: Two 60-minute periods BACKGROUND: The lesson is based on the impact of the Japanese occupation of Korea during World War II on Korean culture and identity. In particular, the lesson focuses on the Japanese campaign in 1940 to encourage Koreans to abandon their Korean names and adopt Japanese names. This campaign was known as “sōshi-kaimei." The purpose of this campaign, along with campaigns requiring Koreans to recite an oath to the Japanese Emperor and bow at Shinto shrines, were to make the Korean people “Japanese” and hopefully, loyal subjects of the Japanese Empire by abandoning their Korean identity and loyalties. These cultural policies and campaigns were key to the Japanese war effort during World War II. The lesson draws from the students’ lives as well as two books: Lost Names: Scenes from a Korean Boyhood by Richard E. Kim and Under the Black Umbrella: Voices from Colonial Korea 1910-1945 by Hildi Kang. CURRICULUM CONNECTION: The lesson is intended to use the major themes from the summer reading book Lost Names: Scenes from a Korean Boyhood to introduce students to one of the five essential questions of the World History II course: How is identity constructed? How does identity impact human experience? In first investigating the origin of their own names and the meaning of Korean names, students can begin to explore the question “How is identity constructed?’ In examining how and why the Japanese sought to change the Korean people’s names, religion, etc during World War II, students will understand how global events such as World War II can impact an individual. -

The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

The K-pop Wave: An Economic Analysis Patrick A. Messerlin1 Wonkyu Shin2 (new revision October 6, 2013) ABSTRACT This paper first shows the key role of the Korean entertainment firms in the K-pop wave: they have found the right niche in which to operate— the ‘dance-intensive’ segment—and worked out a very innovative mix of old and new technologies for developing the Korean comparative advantages in this segment. Secondly, the paper focuses on the most significant features of the Korean market which have contributed to the K-pop success in the world: the relative smallness of this market, its high level of competition, its lower prices than in any other large developed country, and its innovative ways to cope with intellectual property rights issues. Thirdly, the paper discusses the many ways the K-pop wave could ensure its sustainability, in particular by developing and channeling the huge pool of skills and resources of the current K- pop stars to new entertainment and art activities. Last but not least, the paper addresses the key issue of the ‘Koreanness’ of the K-pop wave: does K-pop send some deep messages from and about Korea to the world? It argues that it does. Keywords: Entertainment; Comparative advantages; Services; Trade in services; Internet; Digital music; Technologies; Intellectual Property Rights; Culture; Koreanness. JEL classification: L82, O33, O34, Z1 Acknowledgements: We thank Dukgeun Ahn, Jinwoo Choi, Keun Lee, Walter G. Park and the participants to the seminars at the Graduate School of International Studies of Seoul National University, Hanyang University and STEPI (Science and Technology Policy Institute). -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

K-Pop Fandom in Lima,Perú

Wesleyan ♦ University K-POP FANDOM IN LIMA, PERÚ: VIRTUAL AND LIVE CIRCULATION PATTERNS By Stephanie Ho Faculty Advisor: Dr. Mark Slobin A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Middletown, Connecticut MAY 2015 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mark Slobin, for his invaluable guidance and insights during the process of writing this thesis. I am also immensely grateful to Dr. Su Zheng and Dr. Matthew Tremé for acting as members of my thesis committee and for their considered thoughts and comments on my early draft, which contributed greatly to the improvement of my work. I would also like to thank Gabrielle Misiewicz for her help with editing this thesis in its final stages, and most importantly for supporting me throughout our time together as classmates and friends. I thank the Peruvian fans that took the time to help me with my research, as well as Virginia and Violeta Chonn, who accompanied me on fieldwork visits and took the time to share their opinions with me regarding the Limeñan fandom. Thanks to my friends and colleagues at Wesleyan – especially Nicole Arulanantham, Gen Conte, Maho Ishiguro, Ellen Lueck, Joy Lu, and Ender Terwilliger – as well as Deb Shore from the Music Department, and Prof. Ann Wightman of the Latin American Studies Department. From my pre-Wesleyan life, I would like to acknowledge Francesca Zaccone, who introduced me to K-pop in 2009, and has always been up for discussing the K-pop world with me, be it for fun or for the purpose of helping me further my analyses.