Economic Outlook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 - Select Year

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 2 JOIN OUR MAILING LIST About Us DONATE Blog Contact Us Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Donate FREEDOM OF THE PRESS - View another year - South Africa South Africa Freedom of the Press 2013 - Select year - Freedoms of expression and of the press are protected in the constitution and generally respected in practice, and South Africa is home to vibrant journalists’ and press freedom advocacy organizations that regularly and 2013 SCORES effectively push back against government encroachments. However, several apartheid-era laws and a 2004 Law on Antiterrorism permit authorities to restrict reporting on the security forces, prisons, and mental institutions. In PRESS STATUS September 2012, the Constitutional Court upheld a 2011 Gauteng High Court judgment that the controversial 2009 Film and Publications Amendment Act was unconstitutional. The legislation, ostensibly passed to protect Partly against child pornography and hate speech, was widely criticized by press freedom advocates as a potential means of prepublication censorship. It required any publisher not recognized by the press ombudsman to submit Free potentially “pornographic” or “violence-inciting” materials to a government board for approval, and imposed PRESS FREEDOM SCORE criminal penalties for noncompliance. Journalists and media houses are occasionally threatened with legal action or charged as a result of their work. In 35 November 2011, lawyers for presidential spokesman and African National Congress (ANC) party stalwart Mac Maharaj threatened the independent weekly and online daily Mail & Guardian with criminal prosecution for alleging LEGAL ENVIRONMENT that Maharaj lied to the anticorruption agency regarding his involvement in an arms-deal scandal from the late 1990s, leading the newspaper to censor most of the article in question. -

Umhlanga Rocks

UMHLANGA ROCKS UMHLANGA ROCKS sunny place for shady people A Novel by: Bryan Britton ……………sunny place for shady people UMHLANGA ROCKS This work is dedicated to the memory of Mr Nelson Mandela, Nobel Peace Prize Winner, whose lifetime of endeavour and empathy for his fellow man must continue to inspire. This is the author’s first attempt at a work of fiction. He leaves the world of fact with great reluctance and so the backdrop to the story is mainly factual. ……………sunny place for shady people UMHLANGA ROCKS Direct quotations have been lifted from the Fourth Pillar upon whom South Africans are forced to rely in order to maintain their faltering democracy. In doing this he has often not acknowledged individual pieces but rather recognized the works of members of the Fourth Pillar as a collective. The author is massively grateful for their combined effort in preventing South Africa becoming yet another failed state on the African Continent. Many of the players in this book are real but yet others have had their names changed to protect their innocence. The conclusions, assumptions, assertions and story line are of the author’s making and anyone offended or disapproving is offered a sincere apology. It is the author’s intention only to amuse and inform whilst advertising the amazing place on the eastern shores of South Africa known as Umhlanga Rocks and the inland travel opportunities of the South African province of KwaZulu Natal. - Bryan Britton May 2014 The Index ……………sunny place for shady people UMHLANGA ROCKS Chapter 1 The Place Chapter 2 The Tribes Chapter 3 The Players Chapter 4 The Attraction Chapter 5 The Underbelly Chapter 6 The Drama Chapter 7 The Outcome Chapter 8 The Morality Chapter 9 The End Chapter 1 The Place _______________________________________________________ ……………sunny place for shady people UMHLANGA ROCKS The Colonel blustered into the ‘Sizzling Steak’ with an exasperated ‘good morning all’ to nobody in particular. -

Protecting Zuma Versus Protecting the Constitution

Protecting Zuma versus Protecting the Constitution Leon Hartwell Stellenbosch University, South Africa During his first year in government, Nelson Mandela reminded fellow ANC members at a party conference, that “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” He further noted, “It has happened in many countries that a liberation movement comes to power and the freedom fighters of yesterday becomes members of government.” Some of them, he warned, “forget about the people who put them in power and they become a class, a separate entity who are not accountable to their membership.” He then went on to caution that ANC leaders had to work hard to avoid misrule and tyranny. For the past few years, Madiba’s warnings has been falling on deaf ears. On 5 April 2016, South Africa’s Parliament debated whether President Jacob Zuma should be impeached (Parliament of the Republic of South Africa 2016). It followed an important ruling by the Constitutional Court that Zuma failed to uphold the Constitution when he did not comply with the Public Protector’s remedial action regarding payment for the non-security upgrades to his Nkandla homestead. The Constitutional Court ruled, in no uncertain terms, that “the president failed to uphold, defend and respect the Constitution” (Shange and Quintal 2016). Yet, the ANC stood firm against the notion. Why did they do it? What will be the consequences? What is the problem? After watching the entire Parliamentary ‘debate’ (which was a rather painful exercise), it is evident that there were only a handful of ANC member who attempted to defend Zuma from impeachment on legal grounds. -

A Critical Discourse Analysis of How South African Publics Engaged in the Social Media Platform, Namely Facebook, Over Nkandlagate

A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF HOW SOUTH AFRICAN PUBLICS ENGAGED IN THE SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORM, FACEBOOK, OVER NKANDLAGATE IN 2015 by Sally Kumwenda Student Number: 814039 A Research project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA by course work and Research Report in the Department of Journalism and Media Studies, Faculty of Humanities University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Supervisor: Dr. Glenda Daniels Date March 2016 i DECLARATION I declare that this research report is completely my own, unaided work. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at this or any other university. All the sources and quotes used have been acknowledged accordingly. I am not allowing anybody to use my research without my consent, the consent of my supervisor or the University of the Witwatersrand. __________________________ Sally Kumwenda Date: 15th March 2016 Word count: 29,640 ii ABSTRACT The Nkandlagate scandal, in which the South African President, Jacob Zuma allegedly spent an estimated R246 million of taxpayers’ money on the renovation of his Nkandla residence, created huge public outcry. This reached yet another height in 2015 when Zuma’s administration declared that the President was not going to pay back the money as demanded by the South African publics. The publics of South Africa used social media platforms to express themselves over the decision. Studies have shown that social media platforms provide an opportunity for political mobilisation of publics and their participation in democracy. Using critical discourse analysis, this study seeks to investigate how South African publics engaged in the social media platform, particularly Facebook, over Nkandlagate. -

SOUTH AFRICA: Nkandla

By Mwangi Githahu Capetown, South Africa – Of all the controversies swirling round the figure of President Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma aka Msholozi – his clan praise name – probably the best known and most discussed around South Africa is the issue of his super controversial Nkandla homestead. More than the 783 corruption charges reinstated in April this year after the High Court in Pretoria found that the decision to drop the corruption charges back in 2009 was “irrational” and that they were as serious as the allegations of “state capture”– which is a type of systemic political corruption in which private interests significantly influence a state’s decision-making processes to their own advantage – the issue of Nkandla is the one that has contributed the most to what one media commentator referred to as President Zuma’sannishorribilis. If you have only just returned from deep space, or have never heard of South Africa, Nkandla is the president’s private home in KwaZulu-Natal Province. It is controversial because public funds to the tune of over R246 million (about $17 million) were used to give the homestead an alleged security upgrade. Among the “improvements” made to the South African president’s private home using taxpayer’s money were a helipad, underground bunkers, a chicken run and a swimming pool actually described as a ‘firepool’ – since, it was claimed, the pool was built as a source of water for firefighting Among the “improvements” made to the home by the Ministry of Public Works using taxpayer’s money were: Security fencing around the whole compound, accommodation for the president’s security, a helipad, underground bunkers, a chicken run and most questionable of all, a swimming pool actually described as a ‘firepool’– since, it was claimed, the pool was built as a source of water for firefighting. -

Global and Local Narratives of the South African General Elections

DESPERATELY SEEKING DEPTH: Global and local narratives of the South African general elections on television news, 1994 – 2014 By Bernadine Jones Town Cape Thesis presentedof for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the Centre for Film and Media Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN UniversityAugust 2017 1 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration of own work and publications This thesis is my own work, conducted in Cape Town, South Africa between January 2014 and August 2017. I confirm that I have been granted permission by the University of Cape Town’s Doctoral Degrees Board to include the following publication(s) in my PhD thesis: Jones, B. 2016. Television news and the digital environment: a triadic multimodal approach for analysing moving image media, in African Journalism Studies 37(2): 116-137 2 Acknowledgements What respectable body of work would be complete without expressing ones gratitude to those who have helped carry the author – mind, soul, and sometimes body – through the wilderness of research and analysis? It stands to reason then that I convey my utmost appreciation for my two supervisors, Drs Martha Evans and Wallace Chuma, for guiding me along this path with infinite patience, wisdom, and maddening attention to detail without which I would flounder. -

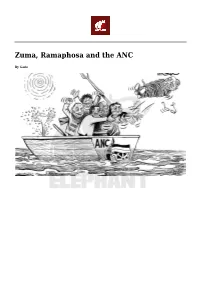

Zuma, Ramaphosa and the ANC

Zuma, Ramaphosa and the ANC By Gado Published by the good folks at The Elephant. The Elephant is a platform for engaging citizens to reflect, re-member and re-envision their society by interrogating the past, the present, to fashion a future. Follow us on Twitter. Zuma, Ramaphosa and the ANC By Gado Cape Town, South Africa – APATHETIC MIDDLE CLASS TAKES TO THE STREETS President Jacob Zuma is not going anywhere in a hurry. However, a number of South Africans are battling to understand why not. As far as they are concerned, factions are rife in the ruling party, there are whispers and dark mutterings about private armies being recruited to defend party headquarters and to infiltrate opposition protests. There have been high-profile sackings from the Cabinet and resignations from parliament. As a result, a normally apathetic middle class has taken to the streets to demonstrate with opposition parties, trade unionists, senior members of the clergy and civil society. These South Africans are also concerned about what they perceive as the securitisation of the state. The recently appointed police minister is talking about fighting fire with fire in his threats to those who dare protest against the state. The acting police commissioner is dismissive of court rulings allowing protests. There is open lawfare in the courts. Parliament is once more discussing a motion of no-confidence even though the ruling party’s numbers in the House mean it is at best a waste of effort. Unhappy South Africans can see signs that that their economy is under attack, with international ratings agency after agency giving the country the thumbs down. -

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 5

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 5 South Africa freedomhouse.org South Africa is home to a vibrant media environment, and press freedom advocacy organizations regularly push back against government encroachments on the rights that journalists enjoy. However, such encroachments became more frequent in 2014, as President Jacob Zuma and the governing African National Congress (ANC) party stepped up the use of laws such as the apartheid-era National Key Points Act. The year also featured an increase in political and economic pressure by the ANC on both private outlets and the public broadcaster—the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC)—as well as an uptick in violence, including the first work-related killing of a journalist in two decades. Legal Environment Freedoms of expression and of the press are protected in the constitution and generally respected in practice. However, several apartheid-era laws and a 2004 Law on Antiterrorism permit authorities to restrict reporting on the security forces, prisons, and any sites or institutions deemed important to the “national interest” by authorities. Journalists and media outlets at times face the threat of legal action as a result of their work, particularly when reporting on prominent political or business figures. Civil defamation cases, sometimes involving large fines, are occasionally brought against members of the press. Prosecutions for criminal defamation are rare. In a prominent recent case, the Pretoria High Court in December 2014 overturned the June 2013 conviction of journalist Cecil Motsepe on criminal defamation charges, for which he had been sentenced to a fine of R10,000 ($950) or 10 months in prison, suspended for four years. -

![Downloads/Morninginamericavo L3i4.Pdf [24 March 2013]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1329/downloads-morninginamericavo-l3i4-pdf-24-march-2013-4561329.webp)

Downloads/Morninginamericavo L3i4.Pdf [24 March 2013]

AN ANALYSIS OF COMMUNITY-POLICE PARTNERSHIPS: A CASE STUDY OF THE THORNHILL POLICING AREA By DEON ELS Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Conflict and Transformation Management at the School of Governmental and Social Sciences in the Faculty of Arts of the NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY Supervisor: Dr. G.J. Bradshaw 2015 DECLARATION FULL NAME: Deon André Els STUDENT NUMBER: 212442473 QUALIFICATION: Master of Arts TITLE OF PROJECT: An Analysis of Community-Police Partnerships: A Case Study of the Thornhill Policing Area DECLARATION: In accordance with Rule G4.6.3, I hereby declare that the above-mentioned dissertation is my own work, and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another university, or for another qualification. SIGNATURE: DATE: 18 November 2014 i DEDICATION I dedicate this research effort to all those heart-sore families I officially engaged with as a young SAPS officer while investigating their beloved ones’ suicides. To this day, I recall the smell of death and the absolute silence while guarding their bodies until first light. I recall the incident of the attractive young girl dressed in brown corduroy pants and the horrific task of climbing over the balcony to enter through an open window while the man’s body blocked the entrance, with the song Hotel California blaring over his radio. The memory of these and other countless suicides, although nearly 30 years ago, remain as crisp in my memory as if it was yesterday. I further dedicate this effort to those people I was fortunate to assist and convince not to commit suicide. -

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014 Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa PO Box 740 Auckland park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 011 381 6000 Fax: +27 011 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 978-1-920446-45-1 © EISA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of EISA. First published 2014 EISA acknowledges the contributions made by the EISA staff, the regional researchers who provided invaluable material used to compile the Updates, the South African newspapers and the Update readers for their support and interest. Printing: Corpnet, Johannesburg CONTENTS PREFACE 7 ____________________________________________________________________ ELECTIONS IN 2014 – A BAROMETER OF SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS AND 9 SOCIETY? Professor Dirk Kotze ____________________________________________________________________ 1. PROCESSES ISSUE 19 Ebrahim Fakir and Waseem Holland LEGAL FRAMEWORK 19 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN ELECTORAL LAW 21 ELECTION TIMETABLE 24 ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 25 NEGATIVE PERCEPTIONS OF ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 26 ELECTORAL SYSTEM 27 VOTING PROCESS 28 WORKINGS OF ELECTORAL SYSTEM 29 COUNTING PROCESS 30 2014 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS – VOTER REGISTRATION 32 STATISTICS AND PARTY REGISTRATION ____________________________________________________________________ 2. SA ELECTIONS 2014: CONTINUITY, CONTESTATION OR CHANGE? 37 THE PATH OF THE PAST: SOUTH AFRICAN DEMOCRACY TWENTY YEARS ON 37 Professor Steven Friedman KWAZULU-NATAL 44 NORTH WEST 48 LIMPOPO 55 FREE STATE 59 WESTERN CAPE 64 MPUMALANGA 74 GAUTENG 77 ____________________________________________________________________ 3 3. -

Opposition Parties Want Zuma Sacked Over Nkandla

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Sunday 26 September 2021 Opposition parties want Zuma sacked over Nkandla Seven opposition parties have vowed to step up a campaign to drive President Jacob Zuma from office after the ANC adopted a report that clears him of responsibility for misspending on his Nkandla homestead, notes a City Press report. DA parliamentary leader Mmusi Maimane said minority party MPs would call for Zuma's removal during the debate on the Nkandla report in the National Assembly today because by defying the Public Protector's findings he had violated the Constitution. In their alternative report on the work done at Nkandla, the seven opposition parties found Zuma was fully aware of the upgrades, notes a Business Day report. The report finds that 'President Zuma knew full well what was unfolding at Nkandla and knew that buildings far in excess of his own home were being built for him.' Zuma's attitude to the overwhelming evidence and findings against him was unbecoming of a President of the Republic; and he 'intended to mislead Parliament about the existence of a bond over his Nkandla property that paid for the upgrades to the property.' The report recommends Zuma be removed from office because he has seriously violated the Constitution by failing to assist and protect the Public Protector, and that he be ordered to repay a percentage of the money spent. ANC Chief Whip Stone Sizani said: 'The thorough and lengthy process through which this committee conducted its business ... cannot be compared to a DA-sponsored propaganda brochure which contains the same obsessive anti-President Zuma rhetoric they canvassed even before the formation of the committee. -

South Africa 2014 Election Updates

1 Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa 14 Park Rd · Richmond · Johannesburg · PO Box 740 · Auckland Park · 2006 · South Africa Tel: (+27) 11 381 6000 · www.eisa.org.za South Africa 2014 Election Updates EISA Election Update Three www.electionupdate.org.za Editorial Team: Ebrahim Fakir, Waseem Holland & Kerryn Kotler; EISA Copy Editing and Proofreading: Professor Craig MacKenzie; University of Johannesburg Website: Duncan Russell SA Elections 2014: Sticks & Stones - Political Intolerance, Violence & Intimidation Contents “The first to defend the rights of other parties? – The ANC and the problem of intimidation in South Africa” page 2 David Bruce, Independent Researcher on behalf of the Community Agency for Social Enquiry (CASE) KwaZulu-Natal page 13 Shauna Mottiar, Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Centre for Civil Society, University of KwaZulu-Natal Gauteng page 17 Waseem Holland, Independent Researcher and Ebrahim Fakir, Manager, Political Parties and Parliamentary Programme at EISA; and 2014 Ruth First Fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg North West page 24 Dr Ina Gouws, North West University, Vaal Triangle Campus Mpumalanga page 30 Oupa Makhalemele, Independent Researcher Limpopo page 34 Ralph Matekga, Director, Clearcontent Research and Consulting Eastern Cape page 37 Malachia Mathoho, Musa Sebugwawo and Stephen Shisanya, Afesis-corplan Free State page 41 Dr Sethulego Matebesi, Chairperson, Department of Sociology, University of the Free State Western Cape page 45 Dr Cherrel Africa, Head of Department, Political Studies, University of Western Cape 2 The first to defend the rights of other parties? – The ANC and the problem of intimidation in South Africa1 David Bruce, Independent Researcher on behalf of the Community Agency for Social Enquiry (CASE) 2 “We fought against no-go areas and will be the first party to defend the right of other parties to campaign wherever they wish”.