York Bridgemasters' Accounts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

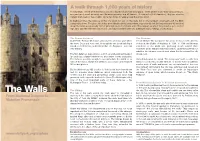

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

Leisure Ride 7, Foss Islands Cycle Track to Murton

YORK CYCLE ROUTE MAP Start & Ride Notes Finish Easy cycle rides 1 Foss Islands Cycle Track takes you all the way for leisure to Osbaldwick along the route of the former Derwent Valley Light Railway which amongst One of a series of short rides other things, brought sugar beet from the suitable for most ages and abilities York countryside to Rowntree’s factory. It ran from Ce ntre 1913 until about 1980. Sustrans (Sustainable River Ouse Time: 1 hr 10 mins Transport) owns and manages the track as part Part of the York Cycle Route Map of Route 66. 2 Time: This ride may take 40 minutes on the way there and St. Nicholas Field – local nature reserve and 30 minutes on the return journey. environmental community centre. Route info: Approx 7 miles. Half on Foss Islands cycle track Ride 3 Potential new housing scheme site. Consultations which is motor traffic free until Osbaldwick then on country N 7 roads with traffic. The traffic varies with time of day and are taking place with planners to make sure the whether it is market day at the Cattle Market. cycle track is preserved and improved. 4 Holiday cottages. 5 Yorkshire Museum of Farming now called Murton Park because it incorporates a section of the Derwent Valley Light Railway, a Viking village and a Roman Fort. These are used in Cycling City York is a community-led partnership project involving City of York Council, cycle campaign groups, major employers, education themed school visits. You can visit the café and healthcare providers and cycle retailers. -

Newsmail York

York NewsMail No 8 August 2021 CONTENTS Page Chairman’s Message 3 Editorial 4 Groups 4 Talks 8 Membership Matters 9 Open Day 10 Travel 11 York u3a Website 11 Volunteers for Research 12 Members’ Contributions 12 Cryptic Crossword 14 Quizzes 14 Committee 16 Vacancies 16 Office Opening Hours 16 Puzzle Solutions 17 Aldborough Trip 18 Beamish Trip 20 FRONT COVER PICTURE Our front cover picture continues to show scenes from around York which reflect the season. No prizes for guessing where this one was taken! It’s great to see York Races back in action – and on such a glorious day. If you’d like to submit a photo for the front cover of the October edition of NewsMail showing something typically autumnal in York, I’d be happy to receive it attached to an email sent to me via [email protected] by the deadline date of Monday 20 September. Nick David, Editor 2 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE So, seventeen months after the first lockdown, the appointed date for ‘Freedom Day’ has finally arrived, despite the data. Speaking for myself, I can’t say I feel freshly freed, and none of our members whom I have spoken to appear to be feeling particularly liberated either. This could have something to do with the fact that daily Covid infections have reached 50,000 and are predicted to double relatively soon, with the toll of hospitalisations and deaths that will follow, including those of some doubly-vaccinated victims, and the inevitable risk of the development of new variants. Analogies with the charge of the Light Brigade come to mind. -

The Northern Clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Altazin, Keith, "The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 543. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NORTHERN CLERGY AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Keith Altazin B.S., Louisiana State University, 1978 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2003 August 2011 Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation would have not been possible without the support, assistance, and encouragement of a number of people. First, I would like to thank the members of my doctoral committee who offered me great encouragement and support throughout the six years I spent in the graduate program. I would especially like thank Dr. Victor Stater for his support throughout my journey in the PhD program at LSU. From the moment I approached him with my ideas on the Pilgrimage of Grace, he has offered extremely helpful advice and constructive criticism. -

Mid-Term Report to Guildhall Ward Residents Q & a with Denise Craghill, Green Party Councillor for Guildhall Ward Q

OCTOBER 2017 guildhall GREENlight SERVING MARYGATE, BOOTHAM, GILLYGATE, THE GROVES, WIGGINGTON ROAD, HAXBY ROAD, MONKGATE, HUNTINGTON ROAD, LAYERTHORPE, FOSS ISLAND, THE CITY CENTRE, ALDWARK, HUNGATE, TOWER STREET, WALMGATE/NAVIGATION AND LAWRENCE STREET AREAS. Mid-Term Report to Guildhall Ward Residents Q & A with Denise Craghill, Green Party councillor for Guildhall ward Q. ‘It’s a bit past halfway through your on city wide issues that affect everyone. Secondly – term in office with the next Council Some problems can be sorted quickly, taking a lead on promoting consultation elections set for May 2019 – how do others can take a very long time, which with residents. is frustrating for residents and councillors you think you’re doing?’ I organised the well-received Ward alike! I don’t think I’ve done everything right A. ‘I was very honoured to be elected as Walkabouts Guildhall councillors did last but I have learned an awful lot and keep the first Green Party councillor for Guildhall year, partly to get feedback on how to learning all the time. I like to think I don’t ward in May 2015. I’ve been working hard to spend our ward highways budget. respond to local queries and get progress give up and will keep coming back to some knotty issues until progress is made.’ Even though getting the Council to implement the ideas is very slow going – Q. ‘What 3 things are you most I raised this delay at the last Full Council proud of so far?’ meeting in July – this was a good way to A. -

THE REFORMATION in LEICESTER and LEICESTERSHIRE, C.1480–1590 Eleanor Hall

THE REFORMATION IN LEICESTER AND LEICESTERSHIRE, c.1480–1590 Eleanor Hall Since its arrival in England, never did Christianity undergo such a transformation as that of the Reformation. By the end of the sixteenth century the official presence of Catholicism had almost entirely disappeared in favour of Protestantism, the permanent establishment of which is still the institutional state religion. This transformation, instigated and imposed on the population by a political elite, had a massive impact on the lives of those who endured it. In fact, the progression of these religious developments depended on the compliance of the English people, which in some regions was often absent. Indeed, consideration must be given to the impact of the Reformation on these localities and social groups, in which conservatism and nostalgia for the traditional faith remained strong. In spite of this, the gradual acceptance of Protestantism by the majority over time allowed its imposition and the permanent establishment of the Church of England. Leicestershire is a county in which significant changes took place. This paper examines these changes and their impact on, and gradual acceptance by, the various religious orders, secular clergy, and the laity in the town and county. Important time and geographical comparisons will be drawn in consideration of the overall impact of the Reformation, and the extent to which both clergy and laity conformed to the religious changes imposed on them, and managed to retain their religious devotion in the process. INTRODUCTION The English Reformation is one of the periods in history that attracts a high level of interest and debate. -

For Sale Freehold Light Industrial Warehouse Unit On

For Sale Freehold Light Industrial Warehouse Unit on the Fringe of the City Centre 10 Redeness Street, York, YO31 7UU Established Mixed Commercial Location Good Access to Inner City Ring Road Walking Distance from City Centre Benefit of short term income 2,665 sq ft (247.59 sq m) Lawrence Hannah for themselves and for the vendors or lessor of this property for whom they act, give notice that – i) these particulars are a general outline only, for the guidance of prospective purchasers or tenants, and do not constitute the whole or any part of an offer or contract, ii) Lawrence Hannah cannot guarantee the accuracy of any description, dimensions, references to condition, necessary permissions for use and occupation and other details contained herein and prospective purchasers or tenants must not rely on them as statements of fact or representations and must satisfy themselves as to their accuracy, iii) rents quoted in these particulars may be subject to VAT in addition; iv) Lawrence Hannah will not be liable, in negligence or otherwise, for any loss arising from the use of these particulars; v) the reference to any plant, machinery, equipment, services, fixtures or fittings at the property shall not constitute a representation (unless otherwise stated) as to its state or condition or that it is capable of fulfilling its intended function. Prospective purchasers/tenants should satisfy themselves as to the fitness of such items for their requirements; vi) no employee of Lawrence Hannah has any authority to make or give any representation or warranty or enter into any contract whatever in relation to the property. -

York's City Walls

Fishergate Postern Tower F P T Open Days in 2021 YORK’S CITY Sat 22nd May = Re-opening after lockdown Fishergate Postern Tower (FPT) was built around 1505. It Sat 29th May = Late Spring BH weekend is at the end of Piccadilly, beside a little gateway at an Mon 31st May = Late Spring BH Monday WALLS end of the walls. Water once filled the gap between this Sat 19th June tower and York Castle. It has four floors, a spiral stair- Sat 3rd July case, an unusually complete Tudor toilet and many ma- Sat 17th July sons’ marks. The roof was added in the late 1500’s; this Sat 14th August = York Walls Festival 2021 turned open battlements into the row of square windows Sun 15th August = York Walls Festival 2021 This leaflet is produced by the Friends of York all round the top floor. Sat 28th August = Late Summer BH weekend Sat 11th September = Heritage Open Days Walls to help you to understand and enjoy Friends of York Walls lease the tower from the City of Sat 18th September = Heritage Open Days York’s old defensive walls. We promote the York Council. Displays here are about the tower and the Sat 2nd October City Walls and open a Tudor tower on them. history of the City Walls. Entry is free on our open days, Sat 23rd October Look inside this leaflet for a map of the Walls, and we can also open for payment. Planned Open Day Sat 30th October = Halloween Saturday photos and facts about the Walls. dates are listed in the next column. -

43 Layerthorpe York Yo31 7Uz to LET UNIT 1

TO LET 43 LayErThOrpE UNIT 1 yOrk yO31 7Uz Location The Cathedral City of York is the principal commercial and retail centre for North Yorkshire. The city has a large, affluent primary catchment population of 478,000 and is one of the UK’s major tourist centres with an estimated 6.7 million tourists visiting the city in 2014. The property is situated in Layerthorpe, one of the main thoroughfares into York city centre which links directly to the inner city ring road. As such, the area is popular with large retailers wanting a city centre presence but with the benefit of customer parking and easy access to the inner and outer ring roads. The property is situated adjacent to Halfords and in close proximity to Carpet Right, Topps Tiles, National Tyres, Asda, Morrisons and Waitrose. Description - Brand new B8 / trade counter industrial unit - Ground floor: slab reinforced concrete - Maximum loading of 8lbs / sq ft - Main structure: single span steel portal frame with operational height of 9.8 ft - External walls: full height profile steel cladding - Pitched roof: is insulated profile steel cladding with roof lights - Windows: powder coated aluminium, double glazed - Insulated roller shutter door to the rear - WC and kitchen facilities - 3 phase 415v incoming electricity supply Total 3,175 sq ft 46 BOOTham yOrk yO30 7Bz 01904 622226 www.stapletonwaterhouse.com TO LET 43 LayErThOrpE UNIT 1 yOrk yO31 7Uz Car Parking There are 9 car parking spaces allocated to the unit. Messrs. Waterhouse for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property -

A Unique Opportunity in the Uk's Best Place to Live and Work

REDEFINING EXCEPTIONAL STUNNING LOCATION | UlTRA CONNECTED | EXQUISITELY APPOINTED 3 A unique opportunity in the UK’s best place to live and work A prestigious, sustainably built, Grade A office building, an integral part of an exceptional mixed use development within the ancient city walls of York. 35,000 square feet Dedicated car parking BREEAM Excellent Platinum WiredScore Connectivity Adjacent to York Railway Station 5 EXC EPTIONAL WORKSPACE T he development represents a unique and future-proofed opportunity to invest in York’s evolution as a meeting point for business, ideas and creativity for two millennia. It will lead the city’s next exciting phase, creating a new destination at the heart of an exceptional living and working culture and attracting the best employees seeking superb city living and working - at a fraction of the cost of London or Paris. CGI 7 STUNNING LOCATION 9 FOR LIVING AND WORKING Bringing enviable choice to the work/life _ Shambles Market and outdoor street food balance, Hudson Quarter will attract the best seven days a week. employees seeking the best in city living and _ A city of festivals: from Vikings, to Aesthetica working. They will have access to all of the UK Film Festival to Chocolate, York has more major cities, Yorkshire’s stunning countryside museums per square mile than any other city and coast and enjoy some of the finest retail in Europe and Yorkshire more Michelin Star and leisure in Europe, on their doorstep. restaurants than anywhere else in the UK _ Superbly sited within the famous city walls: a outside London. -

“Still More Glorifyed in His Saints and Spouses”: the English Convents in Exile and the Formation of an English Catholic Identity, 1600-1800 ______

“STILL MORE GLORIFYED IN HIS SAINTS AND SPOUSES”: THE ENGLISH CONVENTS IN EXILE AND THE FORMATION OF AN ENGLISH CATHOLIC IDENTITY, 1600-1800 ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History ____________________________________ By Michelle Meza Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Gayle K. Brunelle, Chair Professor Robert McLain, Department of History Professor Nancy Fitch, Department of History Summer, 2016 ABSTRACT The English convents in exile preserved, constructed, and maintained a solid English Catholic identity in three ways: first, they preserved the past through writing the history of their convents and remembering the hardships of the English martyrs; that maintained the nuns’ continuity with their English past. Furthermore, producing obituaries of deceased nuns eulogized God’s faithful friends and provided an example to their predecessors. Second, the English nuns cultivated the present through the translation of key texts of English Catholic spirituality for use within their cloisters as well as for circulation among the wider recusant community to promote Franciscan and Ignatian spirituality. English versions of the Rule aided beginners in the convents to faithfully adhere to monastic discipline and continue on with their mission to bring English Catholicism back to England. Finally, as the English nuns looked toward the future and anticipated future needs, they used letter-writing to establish and maintain patronage networks to attract novices to their convents, obtain monetary aid in times of disaster, to secure patronage for the community and family members, and finally to establish themselves back in England in the aftermath of the French Revolution and Reign of Terror.