New Citizen's Activism in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kejriwal-Ki-Kahani-Chitron-Ki-Zabani

केजरवाल के कम से परेशां कसी आम आदमी ने उनके ीमखु पर याह फेकं. आम आदमी पाट क सभाओं म# काय$कता$ओं से &यादा 'ेस वाले होते ह). क*मीर +वरोधी और भारत देश को खं.डत करने वाले संगठन2 का साथ इनको श5ु से 6मलता रहा है. Shimrit lee वो म8हला है िजसके ऊपर शक है क वो सी आई ए एज#ट है. इस म8हला ने केजरवाल क एन जी ओ म# कु छ 8दन रह कर भारत के लोकतं> पर शोध कया था. िजंदल ?पु के असल मा6लक एस िजंदल के साथ अAना और केजरवाल. िजंदल ?पु कोयला घोटाले म# शा6मल है. ये है इनके सेकु लCर&म का असल 5प. Dया कभी इAह# साध ू संत2 के साथ भी देखा गया है. मिलमु वोट2 के 6लए ये कु छ भी कर#गे. दंगे के आरो+पय2 तक को गले लगाय#गे. योगेAF यादव पहले कां?ेस के 6लए काम कया करते थे. ये पहले (एन ए सी ) िजसक अIयJ सोKनया गाँधी ह) के 6लए भी काम कया करते थे. भारत के लोकसभा चनावु म# +वदे6शय2 का आम आदमी पाट के Nवारा दखल. ये कोई भी सकते ह). सी आई ए एज#ट भी. केजरवाल मलायमु 6संह के भी बाप ह). उAह# कु छ 6सरफरे 8हAदओंु का वोट पDका है और बाक का 8हसाब मिलमु वोट से चल जायेगा. -

Anti-Corruption Movement: a Story of the Making of the Aam Admi Party and the Interplay of Political Representation in India

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2019, Volume 7, Issue 3, Pages 189–198 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v7i3.2155 Article Anti-Corruption Movement: A Story of the Making of the Aam Admi Party and the Interplay of Political Representation in India Aheli Chowdhury Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, 11001 Delhi, India; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 30 March 2019 | Accepted: 26 July 2019 | Published: 24 September 2019 Abstract The Aam Admi Party (AAP; Party of the Common Man) was founded as the political outcome of an anti-corruption move- ment in India that lasted for 18 months between 2010–2012. The anti-corruption movement, better known as the India Against Corruption Movement (IAC), demanded the passage of the Janlokpal Act, an Ombudsman body. The movement mobilized public opinion against corruption and the need for the passage of a law to address its rising incidence. The claim to eradicate corruption captured the imagination of the middle class, and threw up several questions of representation. The movement prompted public and media debates over who represented civil society, who could claim to represent the ‘people’, and asked whether parliamentary democracy was a more authentic representative of the people’s wishes vis-à-vis a people’s democracy where people expressed their opinion through direct action. This article traces various ideas of po- litical representation within the IAC that preceded the formation of the AAP to reveal the emergence of populist repre- sentative democracy in India. It reveals the dynamic relationship forged by the movement with the media, which created a political field that challenged liberal democratic principles and legitimized popular public perception and opinion over laws and institutions. -

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65533 District 1 A PAULINE ABADILLA DORIE ARCHETA ELNA AVELINO #### BOBBY BAKER KRISTA BOEHM THOMAS CARLSON #### ARTHUR DILAY ASHLEY HOULIHAN KIM KAVANAGH #### THERESA KUSTA ELENA MAGUAD MARILYN MC LEAN #### DAVID NEUBAUER VICKY SANCHEZ MARIA SCIACKITANO #### RICHARD ZAMLYNSKI #### 65535 District 1 CN CAROLYN GOSHEN BRIAN SCHWARZ PATRICIA TAYLOR #### 65536 District 1 CS KIMBERLY HAMMOND MARK SMITH #### 65537 District 1 D KENNETH BRAMER KARLA BURN TOM HART #### BETSY JOHNSON C. SKOOG #### 65539 District 1 F DAVID GAYTON RACHEL PERKOWITZ LIZZET STONE #### RAYMOND SZULL JOYCE VOLL MICHAEL WITKOWSKI #### 65540 District 1 G GARY EVANS #### 65541 District 1 H BRENDA BIERI JO ANNE NELSON JERRY PEABODY #### GLENN POTTER JERRY PRINE #### Monday, July 02, 2018 Page 1 of 210 Silver Centennial Awards U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65542 District 1 J SHAWN BLOBAUM SEAN BRIODY GREG CLEVENGER #### MITCHELL COHEN TONI HOARLE KEVIN KELLY #### DONALD MC COWAN JAMES WORDEN #### 65545 District 2 T1 MELISSA MARTINEZ MIKE RUNNING SHAWN WILHELM #### RE DONN WOODS #### 65546 District 2 T2 ROBERT CLARK RANDAL PEBSWORTH TOM VERMILLION #### 65547 District 2 T3 JOHN FEIGHERY TARA SANCHEZ #### 65548 District 2 E1 BRYAN ALLEN KENNETH BAKER JAMES BLAYLOCK #### STACY CULLINS SONYA EDWARDS JANNA LEDBETTER #### JOE EDD LEDBETTER KYLE MASTERS LYNDLE REEVES #### JAMES SENKEL CAROLYN STROUD HUGH STROUD #### DIANA THEALL CYNTHIA WATSON #### 65549 District 2 E2 JERRY BULLARD JIMMIE BYROM RALPH CANO #### CHRISANNE CARRINGTON SUE CLAYTON RODNEY CLAYTON #### GARY GARCIA THOMAS HAYFORD TINA JACOBSEN #### JOHN JEFFRIES JOANNA KIMBRELL ELOY LEAL #### JEREMY LONGORIA COURTNEY MCLAUGHLIN LAURIS MEISSNER #### DARCIE MONTGOMERY KINLEY MURRAY CYNTHIA NAPPS #### SIXTO RODRIGUEZ STEVE SEWELL WILLIAM SEYBOLD #### DORA VASQUEZ YOLANDA VELOZ CLIFFORD WILLIAMSON #### LINDA WOODHAM #### Monday, July 02, 2018 Page 2 of 210 Silver Centennial Awards U.S. -

Immigrant Fiction, Religious Ritual, and the Politics of Liminality, 1899-1939

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2008 Rights of Passage: Immigrant Fiction, Religious Ritual, and the Politics of Liminality, 1899-1939 Laura Patton Samal University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Samal, Laura Patton, "Rights of Passage: Immigrant Fiction, Religious Ritual, and the Politics of Liminality, 1899-1939. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/343 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Laura Patton Samal entitled "Rights of Passage: Immigrant Fiction, Religious Ritual, and the Politics of Liminality, 1899-1939." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Haddox, Carolyn R. Hodges, Charles Maland Accepted for -

'India Against Corruption'

Frontier Vol. 44, No. 9, September 11-17, 2011 THE ANNA MOMENT ‘India Against Corruption’ Satya Sagar TO CALL ANNA HAZARE'S crusade against corruption a 'second freedom movement' may be hyperbole but in recent times there has been no mass upsurge for a purely public cause, that has captured the imagination of so many. For an Indian public long tolerant of the misdeeds of its political servants turned quasi-mafia bosses this show of strength was a much-needed one. In any democracy while elected governments, the executive and the judiciary are supposed to balance each other's powers, ultimately it is the people who are the real masters and it is time the so-called 'rulers' understand this clearly. Politicians, who constantly hide behind their stolen or manipulated electoral victories, should beware the wrath of a vocal citizenry that is not going to be fooled forever and demands transparent, accountable and participatory governance. The legitimacy conferred upon elected politicians is valid only as long as they play by the rules of the Indian Constitution, the laws of the land and established democratic norms. If these rules are violated the legitimacy of being 'elected' should be taken away just as a bad driver loses his driving license or a football player is shown the red card for repeated fouls. The problem people face in India is clearly that there are no honest 'umpires' left to hand out these red cards anymore and this is not just the problem of a corrupt government or bureaucracy but of the falling values of Indian society itself. -

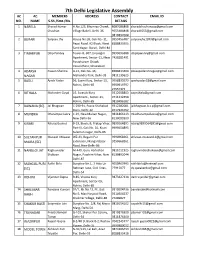

List of MLA Contact Details

7th Delhi Legislative Assembly AC AC MEMBERS ADDRESS CONTACT EMAIL ID NO. NAME S.Sh./Smt./Ms. DETAILS 1 NARELA Sharad Kumar H.No.123, Bhumiya Chowk, 8687686868 [email protected] Chauhan Village Bakoli, Delhi-36 9555484848 [email protected] 9818892004 2 BURARI Sanjeev Jha House No.09, Gali No.-11, 9953456787 [email protected] Pepsi Road, A2 Block, West 8588833505 Sant Nagar, Burari, Delhi-84 3 TIMARPUR Dilip Pandey Tower-B, 607, Dronagiri 9999696388 [email protected] Apartment, Sector-11, Near 7428281491 Parashuram Chowk Vasundhara, Ghaziabad 4 ADARSH Pawan Sharma A-13, Gali No.-36, 8588833404 [email protected] NAGAR Mahendra Park, Delhi-33 9811139625 5 BADLI Ajesh Yadav 56, Laxmi Kunj, Sector-13, 9958833979 [email protected] Rohini, Delhi-85 9990919797 27557375 6 RITHALA Mohinder Goyal 19, Swastik Kunj 9312658803 [email protected] Apartment., Sector-13, 9711332458 Rohini, Delhi-85 9810496182 7 BAWANA (SC) Jai Bhagwan C-290-91, Pucca Shahabad 9312282081 [email protected] Dairy, Delhi-42 9717921052 8 MUNDKA Dharampal Lakra C-29, New Multan Nagar, 9811866113 [email protected] New Delhi-56 8130099300 9 KIRARI Rituraj Govind B-19, Block,-B, Pratap Vihar, 9899564895 [email protected] Part-III, Gali No. 10, Kirari 9999654895 Suleman nagar, Delhi-86 10 SULTANPUR Mukesh Ahlawat WZ-43, Begum Pur 9990968261 [email protected] MAJRA (SC) Extension, Mangal Bazar 9250668261 Road, New Delhi-86 11 NANGLOI JAT Raghuvinder M-449, Guru Harkishan 9811011925 [email protected] -

Contact Details of NDMC Officials, If Any Updation

NDMC TELEPHONE DIRECTORY 2016 MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL Sr.No Name Designation Tel Off Fax Residence Mobile Email 1. Shri Naresh Kumar Chairman 23743579 [email protected] 23742762 26160814 23742269 Shri Pramod Kumar Jain Personal Assistant - do - - do - 22592356 9911412728 2. Shri Karan Singh Tanwar Vice-Chairman 23360065 9810996000 Shri A.K.Jain Sr.Asstt. 9810634179 3. Commando Surender Member 24676016 9560210225 [email protected] Singh Shri Sandeep Panwar P.A. 24676016 8588833438 4. Dr. Anita Arya Member 23362195 9811299488 [email protected] Ext 3660 Shri D.P.S Rathore Sr. Asstt. to Member 23362195 9868268786 Ext 3660 5. Shri B.S.Bhati Member 23362576 9868283156 [email protected] 6. Shri Abdul Rasheed Member 23361937 23555753 9899120754 [email protected] Ansari Shri Harvinder Kaur P.A. 23361937 [email protected] 7. Shri Arvind Kejriwal CM & Member, NDMC 23392005 23392111 23392212 8. Smt. Meenakashi Lekhi MP & Member, NDMC 26251814 9. Shri D.S.Mishra Additional 23061787 23061061 Secretary(UD) & Member, NDMC 10. Shri Dharmendra Joint Secretary (UD) & 23062826 23062898 26878964 Member, NDMC 11. Shri Dharampal Joint Secretary(DP) & 23386800 23385714 23939050 Member, NDMC 12. Shri Punya Salila Secretary 23890119 23890187 Srivastava (Education/Training & Tech. Education) & Member, NDMC SECRETARY OFFICE Sr.No Name Designation Tel Off Fax Residence Mobile Email 1. Smt.Chanchal Yadav Secretary 23742451 23363094 [email protected] 2. Mr.Neeraj Garg P.A. 23742451 9971911120 3. Mr.Harish Dhingra P.A. 23742451 9582221866 FINANCIAL ADVISOR OFFICE Sr.No Name Designation Tel Off Fax Residence Mobile Email 1. Ms Geetali Tare Financial Advisor 23744765 23343007 9811689774 [email protected] 2. -

An Indian Summer: Corruption, Class, and the Lokpal Protests

Article Journal of Consumer Culture 2015, Vol. 15(2) 221–247 ! The Author(s) 2013 An Indian summer: Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Corruption, class, and DOI: 10.1177/1469540513498614 the Lokpal protests joc.sagepub.com Aalok Khandekar Department of Technology and Society Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Maastricht University, The Netherlands Deepa S Reddy Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Houston-Clear Lake, USA and Human Factors International Abstract In the summer of 2011, in the wake of some of India’s worst corruption scandals, a civil society group calling itself India Against Corruption was mobilizing unprecedented nation- wide support for the passage of a strong Jan Lokpal (Citizen’s Ombudsman) Bill by the Indian Parliament. The movement was, on its face, unusual: its figurehead, the 75-year- old Gandhian, Anna Hazare, was apparently rallying urban, middle-class professionals and youth in great numbers—a group otherwise notorious for its political apathy. The scale of the protests, of the scandals spurring them, and the intensity of media attention generated nothing short of a spectacle: the sense, if not the reality, of a united India Against Corruption. Against this background, we ask: what shared imagination of cor- ruption and political dysfunction, and what political ends are projected in the Lokpal protests? What are the class practices gathered under the ‘‘middle-class’’ rubric, and how do these characterize the unusual politics of summer 2011? Wholly permeated by routine habits of consumption, we argue that the Lokpal protests are fundamentally structured by the impulse to remake social relations in the image of products and ‘‘India’’ itself into a trusted brand. -

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

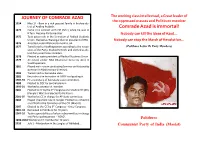

Comrade Azad Is Immortal! 1972 Came Into Contact with CPI (M-L) While He Was in B.Tech

JOURNEY OF COMRADE AZAD The working class intellectual, a Great leader of the oppressed masses and Politburo member 1954 May 14 - Born in a rich peasant family in Krishna dis- trict of Andhra Pradesh. Comrade Azad is immortal! 1972 Came into contact with CPI (M-L) while he was in B.Tech. Became Party member. Nobody can kill the ideas of Azad... 1975 Took active role in the formation of Radical Students Union. Elected as Warangal district president of RSU. Nobody can stop the March of Revolution… 1976 Arrested under MISA and 6 months Jail. 1977 Transferred to Visakhapatnam according to the neces- (Politburo Letter To Party Members) sities of the Party. Studied M.Tech. and elected as dis- trict Party committee member. 1978 Elected as state president of Radical Students Union. 1979 Arrested under NSA (National Security Act) in Visakhapatnam. 1981 Played main role in conducting Seminar on Nationality question in Madras (now Chennai). 1983 Transferred to Karnataka state. 1985 Key role in the formation of AIRSF and guiding it. 1987-93 First secretary of Karnataka state committee. 1990 Elected to COC by central plenum. 1995-01 Worked as secretariat member 2001 Elected to CC by the 9th Congress of erstwhile CPI (ML) [People's War] and elected to Politburo. 2001-07 Worked as CC in-charge for AP state committee. 2004 Played important role in merger. Elected to unified CC and PB after the formation of the CPI (Maoist). 2007 Elected to the CC by 9th Congress - Unity Congress 2001-10 Remained in Politburo for 10 years. 2007-10 Took responsibilities of urban subcommittee in-charge and Party spokesperson - 'AZAD'. -

World Literature for the Wretched of the Earth: Anticolonial Aesthetics

W!"#$ L%&'"(&)"' *!" &+' W"'&,+'$ !* &+' E("&+ Anticolonial Aesthetics, Postcolonial Politics -. $(.%'# '#(/ Fordham University Press .'0 1!"2 3435 Copyright © 3435 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at https:// catalog.loc.gov. Printed in the United States of America 36 33 35 7 8 6 3 5 First edition C!"#$"#% Preface vi Introduction: Impossible Subjects & Lala Har Dayal’s Imagination &' B. R. Ambedkar’s Sciences (( M. K. Gandhi’s Lost Debates )* Bhagat Singh’s Jail Notebook '+ Epilogue: Stopping and Leaving &&, Acknowledgments &,& Notes &,- Bibliography &)' Index &.' P!"#$%" In &'(&, S. R. Ranganathan, an unknown literary scholar and statistician from India, published a curious manifesto: ! e Five Laws of Library Sci- ence. ) e manifesto, written shortly a* er Ranganathan’s return to India from London—where he learned to despise, among other things, the Dewey decimal system and British bureaucracy—argues for reorganiz- ing Indian libraries. -

The Colour Distinction

Resilient Resistance: Understanding the Construction of Positive Ethnocultural Identity in Visible Minority Youth by Elizabeth Shen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration and Leadership Department of Educational Policy Studies University of Alberta © Elizabeth Shen, 2018 ii Abstract Visible minority youth face racism daily at micro, mezzo and macro-levels and yet there is a gap in academic research that examines how these students can combat racism, as they experience it at the micro-level, in order to develop pride toward their minority culture and race. As such, this dissertation explores how visible minority youth, who are living within a dominant culture environment where all levels of racism exist to encourage their assimilation, are able to express positive ethnocultural identity. In doing so, this dissertation seeks to answer the question of: How do visible minority youth build positive personal ethnocultural identity? with the corresponding question of: How do visible minority students externally express ethnocultural identity? Using case study methodology within two schools in the province of Alberta, visible minority adolescent students were interviewed and data were analyzed to gain insight into the various strategies that junior high school (grades 7, 8 and 9) students use to express their ethnocultural identity. I learned that students build ethnocultural identity by: 1. seeking and embracing cultural knowledge; 2. accepting feelings