Hyde Park and University of Chicago History HISTORY of HYDE PARK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume XIII, Number 1 Spring 2019

The Herald Volume XIII, Number 1 Spring 2019 ARCHITECT HOWARD VAN DOREN SHAW AT 150 by William Tyre Friends, in partnership with Returning to Chicago in early 1893, Glessner House, will host a half- he rejoined the firm of Jenney & day symposium on May 11, 2019 to Mundie, and in April, married honor the 150th anniversary of the Frances Wells in a ceremony at First birth of architect Howard Van Presbyterian Church. By early 1894, Doren Shaw, who designed our Shaw established his own practice, National Historic Landmark setting up his office on the top floor designated sanctuary in 1900 of his family home on Calumet following a devastating fire. (See Avenue. He hired a draftsman, page 4, for more information). In Robert G. Work, and quickly this issue, we look back at Shaw’s established a reputation for designing life and several commissions he distinctive residences in a variety of received in the South Loop which architectural styles. exhibit the breadth of his abilities. In 1897, Shaw received his first large Howard Van Doren Shaw was commission through his Yale born on May 7, 1869 to Theodore classmate Thomas E. Donnelley. and Sarah (Van Doren) Shaw. Ave., and joined Second Presbyterian The building at 731 S. Plymouth Theodore was a successful dry by profession of faith in 1885. Shaw Court housed the Lakeside Press, goods merchant and a descendant earned a Bachelor of Arts degree later R. R. Donnelley & Sons. The of an early Quaker settler who from Yale in 1890 and that fall, vaulted fireproof structure with came to America with William entered the Massachusetts Institute reinforced concrete floors showed Penn. -

VILLAGE WIDE ARCHITECTURAL + HISTORICAL SURVEY Final

VILLAGE WIDE ARCHITECTURAL + HISTORICAL SURVEY Final Survey Report August 9, 2013 Village of River Forest Historic Preservation Commission CONTENTS INTRODUCTION P. 6 Survey Mission p. 6 Historic Preservation in River Forest p. 8 Survey Process p. 10 Evaluation Methodology p. 13 RIVER FOREST ARCHITECTURE P. 18 Architectural Styles p. 19 Vernacular Building Forms p. 34 HISTORIC CONTEXT P. 40 Nineteenth Century Residential Development p. 40 Twentieth Century Development: 1900 to 1940 p. 44 Twentieth Century Development: 1940 to 2000 p. 51 River Forest Commercial Development p. 52 Religious and Educational Buildings p. 57 Public Schools and Library p. 60 Campuses of Higher Education p. 61 Recreational Buildings and Parks p. 62 Significant Architects and Builders p. 64 Other Architects and Builders of Note p. 72 Buildings by Significant Architect and Builders p. 73 SURVEY FINDINGS P. 78 Significant Properties p. 79 Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 81 Non-Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 81 Potentially Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 81 Potentially Non-Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 81 Noteworthy Buildings Less than 50 Years Old p. 82 Districts p. 82 Recommendations p. 83 INVENTORY P. 94 Significant Properties p. 94 Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 97 Non-Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 103 Potentially Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 104 Potentially Non-Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 121 Notable Buildings Less than 50 Years Old p. 125 BIBLIOGRAPHY P. 128 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS RIVER FOREST HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION David Franek, Chair Laurel McMahon Paul Harding, FAIA Cindy Mastbrook Judy Deogracias David Raino-Ogden Tom Zurowski, AIA PROJECT COMMITTEE Laurel McMahon Tom Zurowski, AIA Michael Braiman, Assistant Village Administrator SURVEY TEAM Nicholas P. -

NFS Form 10-900-B Ombno

NFS Form 10-900-b OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires Jan. 2005) RECEIVED United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form mi REGISTER OF HISTORIC NATIONAL PARK SERVI This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items, _ X New Submission _ _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Deerpath Hill Estates: an English Garden Development in Lake Forest, Illinois; 1926-1961 B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each). Development of Deerpath Hill Estates, The City Beautiful Movement, 1926-1931 Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945 Post World War II Housing Boom and the Renewal of Deerpath Hill Estates, 1945-1961 C. Form Prepared by name/title Paul Bergmann street & number 238 East Woodland Road telephone 312 381 7314 day city or town Lake Bluff state Illinois zip code 60044 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

A Greeting from Paul Cornell President of the Board of Directors, Augustana Heritage Association

THE AUGUS ta N A HERI ta GE NEWSLE tt ER VOLUME 5 SPRING 2007 NUMBER 2 A Greeting From Paul Cornell President of the Board of Directors, Augustana Heritage Association hautauqua - Augustana - Bethany - Gustavus – Chautauqua...approximately 3300 persons have attended these first five gatherings of the AHA! All C have been rewarding experiences. The AHA Board of Directors announces Gatherings VI and VII. Put the date on your long-range date book now. 2008 Bethany College Lindsborg, Kansas 19-22 June 2010 Augustana College Rock Island, Illinois 10-13 June At Gathering VI at Bethany, we will participate in the famous Midsummers Day activities on Saturday, the 21st. We will also remember the 200th anniversary of the birth of Lars Paul Cornell, President of the Board of Directors Paul Esbjorn, a pioneer pastor of Augustana. We are planning an opening event on Thursday evening, the 19th and concluding on of Augustana - Andover, Illinois and New Sweden, Iowa, and Sunday, the 22nd with a luncheon. 4) Celebrating with the Archbishop of the Church of Sweden in Gathering VII at Augustana will include: 1) Celebrating attendence. the 150th anniversary of the establishment of the Augustana I would welcome program ideas from readers of the AHA Synod, 2) Celebrating the anniversary of Augustana College Newsletter for either Bethany or Augustana. I hope to be present and Seminary, 3) Celebrating the two pioneer'. congregations at both events. How about YOU? AHA 1 Volume 5, Number 2 The Augustana Heritage Association defines, promotes, and Spring 2007 perpetuates the heritage and legacy of the Augustana Evangelical Lutheran Church. -

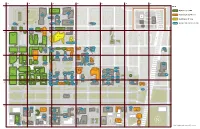

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - -

Insider's Guide

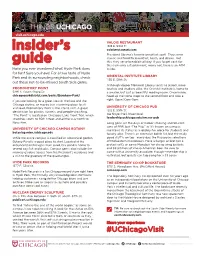

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu VALOIS RESTAURANT 1518 E. 53rd St. insider’s valoisrestaurant.com President Obama’s favorite breakfast spot! They serve classic soul food for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Get guide this: they serve breakfast all day! If you forget cash for this cash-only establishment, worry not, there is an ATM Have you ever wondered what Hyde Park does inside. for fun? Sure you have! For a true taste of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods, check ORIENTAL INSTITUTE LIBRARY 1155 E. 58th St. out these not-to-be-missed South Side gems. Although Harper Memorial Library tends to attract more PROMONTORY POINT tourists and studiers alike, the Oriental Institute is home to 5491 S. South Shore Dr. a smaller, but just as beautiful reading room. Once inside, chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/Burnham-Park/ head up the stone steps to the second floor and take a If you are looking for a great view of the lake and the right. Open 10am-5pm. Chicago skyline, or maybe just a calming place to sit and read, Promontory Point is the site to visit. A great UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUB destination for picnics, sunsets, and people-watching, 1212 E. 59th St. “The Point” is located on Chicago’s Lake Front Trail, which Ida Noyes Hall, lower level stretches south to 95th Street and all the way north to leadership.uchicago.edu/orcsas-pub Navy Pier. Long gone are the days of indoor smoking and 50-cent cans of PBR, but “The Pub,” as it’s known on campus, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CAMPUS BOTANY maintains its status as a reliably fun place for students and botanicgarden.uchicago.edu faculty alike. -

City of Chicago Analysis of Its Proposal Related to Jackson Park, Cook County, Illinois Under the Urban Parks and Recreation Recovery Act Program

City of Chicago Analysis of its Proposal Related to Jackson Park, Cook County, Illinois under the Urban Parks and Recreation Recovery Act Program November 2019 [as revised May 2020] Prepared by the City of Chicago Federal Actions In and Adjacent to Jackson Park Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 UPARR .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Statutory and Regulatory Background ....................................................................... 2 1.2.2 UPARR Grants and Program Requirements at Jackson Park ...................................... 2 1.3 Municipal Consideration of and Approval of the Proposal to Locate the OPC in Jackson Park ............................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance: Existing Recreation Uses and Opportunities ..................................................................................... 6 2.1 Jackson Park: Overview .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Existing Recreation Facilities....................................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Existing Recreation -

Village of Lake Bluff, Illinois

VILLAGE OF LAKE BLUFF, ILLINOIS Summary and Historic Resource Survey: Estate Areas of Lake Bluff 2008 William McCormick Blair House BENJAMIN HISTORIC CERTIFICATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction, 4 Preservation in Lake Bluff and the Role of the Survey 7 Architectural Styles in the Survey Area 11 French Eclectic 12 Tudor Revival 13 Italian Renaissance Revival 14 Mission Revival 15 Mediterranean Revival 16 Colonial Revival/Georgian Revival 17 Modern or Modernist 19 Post Modern 20 History of Lake Bluff Estate Development 21 Ferry Field and Ferry Woods Estate Area 22 Stanley Field Estate 23 Albert A. Sprague, II, Estate 28 Stewart and Priscilla Peck House 32 Mrs. Carolyn Morse Ely House, Gate Houses Orangerie, Wing 33 Harry B. Clow Estate, “Lansdowne” 38 Conway Olmsted House 40 The North Sheridan Road Estate Area 41 “Crab Tree Farm” 41 William McCormick Blair Estate 44 Edward McCormick Blair House 50 Edgar Uihlein Property 51 Lester Armour House 53 Laurence and Pat Booth House 54 Shoreacres Country Club Estate Area 55 Shoreacres Country Club 57 Howard and Lucy Linn House 58 Gustavus Swift, Jr., Property 60 Frank Hibbard House 61 John McLaren Simpson House 62 Frederick Hampton Winston House 63 The Green Bay Road Estate Area 64 Russell Kelley Estate 65 Phelps Kelley Estate 66 William V. Kelley Estate “Stonebridge” 67 Philip D.Armour Estate,“Tangley Oaks, Gate Lodge 69 William J. Quigley Property 72 Ralph Poole House 74 Bibliography 75 Lake Bluff Structures Included on the Illinois Historic Structures Survey, Illinois Historic Landmarks Survey and properties Listed on the National Register of Historic Places 77 Conclusion 78 Acknowledgments 79 Data Base of Properties Surveyed 80 2 VILLAGE OF LAKE BLUFF, ILLINOIS: A SUMMARY AND HISTORIC RESOURCE SURVEY OF THE ESTATE AREAS Published by the Village of Lake Bluff VILLAGE OF LAKE BLUFF Christine Letchinger, Village President BOARD OF TRUSTEES David Barkhausen Rick Lesser Kathleen O’Hara Michael Peters Brian Rener Geoff Surkamer Michael Klawitter, Village Clerk R. -

Preservation Chicago

Preservation Chicago Citizens advocating for the preservation of Chicago’s historic architecture Preservation Chicago Citizens advocating for theJune preservation 9, 2011 of Chicago’s historic architecture Andrew Mooney Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development City Hall – 121 N. LaSalle, 10th Floor JanuaryChicago, 04, 2018IL 60602 Brad Suster June 9, 2011 PresidentPresident Re: Support for St. Boniface church adaptive reuse plan Ward Miller* Ms. EleanorAndrew Gorski, Mooney Deputy Commissioner, Department of Planning and Development,Dear Commissioner Historic Mooney, Preservation Division JacobVice KaplanPresident Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development Jack Spicer* Vice President Mr.I Johnam Citywriting Sadler, Hall in supportChicago– 121 ofN. Departmentthe LaSalle, proposed 10th adaptiveof Transportation Floor reuse plan for the former St. Boniface Church, Secretary locatedChicago, at 1328 W.IL Chestnut60602 and 921 N. Noble, presented to us by IMP Development earlier this ! Debbie Dodge* Ms.week. Abby TheMonroe, latest proposalCoordinating incorporates Planner the, adaptiveDepartment reuse ofof anPlanning existing andhistoric structure coupled Development DebbieTreasurer Dodge with new construction. PresidentGreg Brewer* Re: Support for St. Boniface church adaptive reuse plan SecretaryWard Miller* City of Chicago Board of Directors Efforts to preserve and repurpose this important neighborhood structure date to 1998 and Preservation ! Beth Baxter 121 N. LaSalleDear Commissioner Street Mooney, -

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago's Parks

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago’s Parks by Julia S. Bachrach, Chicago Park District Historian In 1909, Daniel H. Burnham (1846 – 1912) and Edward Bennett published the Plan of Chicago, a seminal work that had a major impact, not only on the city of Chicago’s future development, but also to the burgeoning field of urban planning. Today, govern- ment agencies, institutions, universities, non-profit organizations and private firms throughout the region are coming together 100 years later under the auspices of the Burnham Plan Centennial to educate and inspire people throughout the region. Chicago will look to build upon the successes of the Plan and act boldly to shape the future of Chicago and the surrounding areas. Begin- ning in the late 1870s, Burnham began making important contri- butions to Chicago’s parks, and much of his park work served as the genesis of the Plan of Chicago. The following essay provides Daniel Hudson Burnham from a painting a detailed overview of this fascinating topic. by Zorn , 1899, (CM). Early Years Born in Henderson, New York in 1846, Daniel Hudson Burnham moved to Chi- cago with his parents and six siblings in the 1850s. His father, Edwin Burnham, found success in the wholesale drug busi- ness and was appointed presidet of the Chicago Mercantile Association in 1865. After Burnham attended public schools in Chicago, his parents sent him to a college preparatory school in New England. He failed to be accepted by either Harvard or Yale universities, however; and returned Plan for Lake Shore from Chicago Ave. on the north to Jackson Park on the South , 1909, (POC). -

Spring 2005 the Augustana Heritage Association (AHA) Co-Editors Arvid and Nancy Anderson Is to Define, Promote and Perpetuate

THE AUGUSTANA HERITAGE NEWSLETTER V O L U M E 4 S P R I N G 2 0 0 5 N U M B E R 2 A Letter from Paul Cornell President of the Augustana Heritage Association On Pearl Harbor Day, 2004 Many of our membership remember where we were and what we were doing on that day. Me? Playing ice hockey on Lake Nakomis in Minneapolis, Minnesota on a Sunday afternoon. I can better remember this year’s Gathering IV of the Augustana Heritage Association at Gustavus Adolphus. From the Jussi Bjoerling lecture Thursday through the luncheon on Sunday afternoon. It filled us with joy and thanksgiv- ing. Paul Cornell I realize more and more, and am thankful for, the legacy of Augustana that continues to guide and inspire me in the 7th decade of my life. The renewing of friendships, the words and music of “Songs from Two Homelands,” the presentations of pro- gram teachers, and the ambience (including the weather) of GA made for a great four days. Also to the GA committee for their pre- planning, their on-site operations, and all the behind-the-scenes – a very huge “tack så mycket”. I ask for your prayers and support as the second president of the AHA, stepping into the shoes of Reuben Swanson, is a momen- tous task. We are grateful for his four years of leadership. I am so pleased that he is continuing as a member of the AHA Board. Thank you, Reuben! The Program Committee for the September 14-17, 2006 Gathering V at Chautauqua Institute, Chautauqua, New York has met. -

Self-Guided Tours

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu IF YOU HAVE 4 HOURS self-guided BOTANY POND 57th St. (west of Hutchinson Court) Located in the middle of campus, Botany Pond is the university’s tours biodiversity hotspot, hosting a remarkable variety of animals including ducks, four species of turtles, and a dozen species of dragonflies. For over a century, the pond has served as a tranquil IF YOU HAVE 1 HOUR outdoor study space, relaxation destination, and nexus of intel- lectual life on campus. Plus, rumor has it, if a couple kisses on the MAIN QUAD bridge over Botany Pond, they will get married. 57th St. – 59th St. Between University Ave. and Ellis Ave. architecture.uchicago.edu ROCKEFELLER MEMORIAL CHAPEL 5850 S. Woodlawn Ave. (at E. 59th St.) The centerpiece of the University of Chicago campus rockefeller.uchicago.edu/events is without question its main quadrangle. Designed in 1891 by famed Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb, Rockefeller Memorial Chapel is a hub for ceremonies, the Neo-Gothic style of the Quad lends itself to theater, orchestral performances, chorus groups, classrooms, laboratories, and libraries alike. At vari- concerts, and even circus acts. While you’re there, ous points in the year, the Main Quad is the site of make sure to walk up the 271 steps to the top for 360 everything from quiet study and relaxation to the degree views of Chicago, Lake Michigan, northern bustling Spring Convocation ceremony. Indiana and the port, the Michigan shoreline, and of course, the University itself. Visit the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel website for information on daily Car- HARPER MEMORIAL LIBRARY READING ROOM illon tours, nondenominational religious services, and 1116 E.