National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

Chicago Venue Portfolio

CHICAGO2016 VENUE PORTFOLIO 1750 W. LAKE STREET CHICAGO, IL 60612 [email protected] 773.880.8044 PARAMOUNTEVENTSCHICAGO.COM Paramount Events is ready to help you plan a spectacular event with a delicious SET menu, but to truly make an impact, the perfect backdrop is absolutely essential. THE We have connections at some of the best venues in Chicago, including The Smith on Lake, our own private space that guarantees dedicated service and personalized attention. SCENE You’re welcome to explore the following pages, but don’t forget – we’re here for you! We know every location inside and out and will be happy to offer our suggestions as a guide. ENJOY! TABLE OF 19th Century Club 1 Garfield Park Conservatory 45 Park West 90 1st Ward at Chop Shop 2 Glessner House Museum 46 Parliament 91 CONTENTS 345 North 3 Goodman Theatre 47 Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum 92 360 Chicago 4 Gruen Galleries 48 Pittsfield Building 93 63rd Street Beach House 5 Harold Washington Library Center 49 Pleasant Home 94 A New Leaf 6 Harris Theatre 50 Portfolio Annex 95 Anita Dee Charters 7 Highland Park Community House 51 Power House 96 Aragon Ballroom 8 Hilton | Asmus Contemporary 52 Prairie Production 97 Artifact Events 9 Hinsdale Community House 53 Primitive Art 98 Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University 10 Humboldt Park & Boat House 54 Pritzker Military Museum & Library 99 Baderbräu 11 Ida Noyes Hall at University of Chicago 55 Promontory Point 100 Bentley Gold Coast 12 Ignite Glass Studios 56 Ravenswood Event Center 101 Berger Park 13 International -

August Highlights at the Grant Park Music Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jill Hurwitz,312.744.9179 [email protected] AUGUST HIGHLIGHTS AT THE GRANT PARK MUSIC FESTIVAL A world premiere by Aaron Jay Kernis, an evening of mariachi, a night of Spanish guitar and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on closing weekend of the 2017 season CHICAGO (July 19, 2017) — Summer in Chicago wraps up in August with the final weeks of the 83rd season of the Grant Park Music Festival, led by Artistic Director and Principal Conductor Carlos Kalmar with Chorus Director Christopher Bell and the award-winning Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park. Highlights of the season include Legacy, a world premiere commission by the Pulitzer Prize- winning American composer, Aaron Jay Kernis on August 11 and 12, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus and acclaimed guest soloists on closing weekend, August 18 and 19. All concerts take place on Wednesday and Friday evenings at 6:30 p.m., and Saturday evenings at 7:30 p.m. (Concerts on August 4 and 5 move indoors to the Harris Theater during Lollapolooza). The August program schedule is below and available at www.gpmf.org. Patrons can order One Night Membership Passes for reserved seats, starting at $25, by calling 312.742.7647 or going online at gpmf.org and selecting their own seat down front in the member section of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. Membership support helps to keep the Grant Park Music Festival free for all. For every Festival concert, there are seats that are free and open to the public in Millennium Park’s Seating Bowl and on the Great Lawn, available on a first-come, first-served basis. -

I. Introduction A. Overview of Jackson Park

Jackson Park Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) March 2018 – Data and Community Input Report Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 A. Overview of Jackson Park Hospital 3 B. Defining Community for the CHNA 3 C. Community Health Needs Assessment Methods/Process 6 II. Health Status in the Community – Health Indicator Data 7 A. Social, Economic, and Structural Determinants of Health 7 B. Behavioral Health – Mental Health and Substance Use 19 C. Chronic Disease 24 D. Access to Care 39 III. Health Status in the Community – Community & Stakeholder Input 46 A. Community Focus Groups 46 B. Key Informant Interviews 49 IV. Health Status in the Community – Maps of Community Resources 51 V. Summary of Jackson Park Hospital’s Community Health 60 Implementation Activities – 2015-2018 A. Senior Healthcare Program 60 B. Community Partnerships and Outreach 61 C. Outpatient Services 62 D. In Development – Substance Abuse Program 63 Appendix A. Written Comments from Focus Group Participants 63 Appendix B. Focus Group Questions 64 2 I. Introduction A. Overview of Jackson Park Hospital Jackson Park Hospital & Medical Center is a 256-bed short-term comprehensive acute care facility serving the south side of Chicago for nearly 100 years. The hospital offers full medical, surgical, obstetric, psychiatric, and medical stabilization (detox) services as well as medical sub-specialties including cardiology, pulmonary, gastrointestinal disease, renal, orthopedics, ENT, ophthalmology, infectious disease, HIV, hematology/oncology and geriatrics. Quality ambulatory care is provided onsite through the family medicine center and senior health center. The hospital also provides medical education and training through its family medicine residency program and several affiliated medical schools. -

Hoops in the Hood 2019 Summer Schedule

HOOPS IN THE HOOD ▪ 2019 SUMMER SCHEDULE 13th Annual Cross-City Tournament with LISC Chicago and the Chicago Park District: Saturday, August 17, 2019 on Columbus Dr. between Balbo and Roosevelt – Games start at 10am As of June 18, 2019 and subject to change. Please check with organizer to confirm. Auburn Gresham Who: The ARK of St. Sabina When: Tuesdays, July 2- August, 13, 5:00 - 7:00pm *Fridays, July 19 and August 23, 6:00 - 9:00pm Location(s): Tuesdays, July 2 – August 13: ARK of St. Sabina – 7800 S. Racine Ave. Fridays, July 19 and August 23: Renaissance Park - 1300 W. 79th St. Contact: Courtney Holmon or Cliff Davis ▪ [email protected] / [email protected] ▪ 773-483-4333 / 773-496-4137 ▪ www.thearkofstsabina.org Austin and Humboldt Park Who: BUILD, Inc. When: Fridays, June 28 - August 16, 2:00 – 7:00pm Location(s): June 28: BUILD, Inc. - 5100 W. Harrison St. July 12: 1640 N. Drake Ave. July 19: 4700 W. Gladys Ave. July 26: 3300 W. Le Moyne St. August 2: 4700 W. Van Buren St. August 9: 3200 W. Le Moyne St. August 16: 4700 W. Monroe St. Contact: Mark Thornton ▪ [email protected] ▪ 773-630-2912 ▪ https://www.buildchicago.org Back of the Yards Who: Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council When: Fridays, July 12 – August 16, 3:00 – 7:00pm Location(s): July 12: Sherman Park - 1301 W. 52nd St. July 19: Cornell Park - 1809 W. 50th St. July 26: Sherman Park – 1301 W. 52nd St. August 2: Kelly Park - 2725 W. 41st St. -

Columbus Park Framework Plan

Columbus Park Framework Plan Prepared By: Department of Planning and Development Chicago Park District Table of Contents Contributors Page 2 Location Page 3 Aerial Maps Page 3 Rendering Page 5 History Page 6 Statistics Page 8 Process Page 9 Concept Plan Goals Page 11 Key Challenges Page 12 Major Recommendations Page 13 Page 1 Contributors Chicago Park District Staff § Daniel M. Purciarello (Deputy Director of Planning and Development) § Anne Miller (Project Manager) Page 2 Location: Aerial Maps Columbus Park Aerial View Page 3 Aerial Maps (continued) Columbus Park One Mile Radius Page 4 Location: Rendering Columbus Park Rendered Drawing Page 5 Location: History Columbus Park is considered the masterpiece of Jens Jensen, now known as dean of Prairie-style landscape architecture. The project, Jensen's only opportunity to create an entirely new large park in Chicago, represents the culmination of years of his conservation efforts and design experimentation. Appointed as West Park Commission General Superintendent and Chief Landscape Architect in 1905, Jensen re-designed Humboldt, Garfield, and Douglas Parks and began creating small parks such as Eckhart and Dvorak. After losing political support in 1910, he shifted his role to consulting landscape architect. Two years later, the commissioners acquired 144 acres of farmland at the western boundary of Chicago. They named the new park for Christopher Columbus (c. 1451-1506), the famous Italian explorer who "discovered" America while in the service of Spain. Jensen's vision for Columbus Park was inspired by the unimproved site's natural history and topography. Convinced that it was an ancient beach, Jensen designed a series of berms, like glacial ridges, encircling the flat interior part of the park. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Promontory Point th other names/site number 55 Street Promontory Name of Multiple Property Listing (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 5491 South Shore Drive not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60615 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Historic Preservation Agency State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

2016 Popular Annual Financial Report

CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT Chicago, Illinois Children First Built to Last Best Deal in Town Extra Effort Popular Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended December 31, 2016 Prepared by the Chief Financial Officer and the Office of the Comptroller Rahm Emanuel, Mayor, City of Chicago Jesse H. Ruiz, President of the Board of Commissioners Michael P. Kelly, General Superintendent and Chief Executive Officer Steve Lux, Chief Financial Officer Cecilia Prado, CPA, Comptroller TABLE OF CONTENTS Commissioner’s Letter…………………………………………………………………………………………...….1 Comptroller’s Message……………………………………………………………………………………………...2 Organizational Structure & Management…………...……………………………………………………..3 Map of Parks……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Staffed Locations…………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..5 Operating Indicators………………………………………………………………………………………………....6 CPD Spotlight………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…7 Core Values Children First……………………………………………………………………………………………………...8 Best Deal in Town……………………………………………………..………………………………………..9 Built to Last……………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 Extra Effort………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Management’s Discussion & Analysis………………………………………………………………….12-16 Local Economy………………………………………………………………………………………………………...17 Capital Improvement Projects………………………………………………………………………………….18 Community Efforts…………………………………………………………………………………………………..19 Privatized Contracts………………………………………………………………………………………………...20 Featured Parks………………………………………………………………………………....inside back cover Contact Us…………………………………………………………………………………………………..back -

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015 www.nrpa.org/Innovation-Labs Welcome and Introductions Mike Kelly Superintendent and CEO Chicago Park District Kevin O’Hara NRPA Vice President of Urban and Government Affairs www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Economic Impact of Parks The Chicago Story Antonio Benecchi Principal, Civic Consulting Alliance Chad Coffman President, Global Economics Group www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Impact of the Chicago Park District on Chicago’s Economy NRPA Innovation Lab 30 July 2015 The charge: is there a way to measure the impact of the Park Districts assets? . One of the largest municipal park managers in the country . Financed through taxes and proceeds from licenses, rents etc. Controls over 600 assets, including Parks, beaches, harbors . 11 museums are located on CPD properties . The largest events in the City are hosted by CPD parks 5 Approach summary Relative improvement on Revenues generated by value of properties in parks' events and special assets proximity . Hotel stays, event attendance, . Best indicator of value museum visits, etc. by regarding benefits tourists capture additional associated with Parks' benefit . Proxy for other qualitative . Direct spending by locals factors such as quality of life indicates economic . Higher value of properties in significance driven by the parks' proximity can be parks considered net present . Revenues generated are value of benefit estimated on a yearly basis Property values: tangible benefit for Chicago residents Hypothesis: . Positive benefit of parks should be reflected by value of properties in their proximity . It incorporates other non- tangible aspects like quality of life, etc. -

Previous Winners of the Chicago River Blue Awards

Previous Winners of the Chicago River Blue Awards 2016 Blue Ribbon -Horner Park Ecological Restoration United States Army Corps of Engineers Silver Ribbon -Downtown Glenview Streambank Stabilization Village of Glenview -150 N. Riverside Riverside Investment and Development - Chicago Riverwalk (Phase II) Ross Barney Architects Green Ribbon -New City Structured Development -The Cal-Sag Trail (Western Portion) Forest Preserves of Cook County -Hydrology Improvements at Big Marsh Structured Development -Disinfection at O’Brien and Calumet WRP, Opening of Thornton Reservoir Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago -Chicago Botanic Garden North Lake Shoreline Restoration Project Chicago Botanic Garden 2015 Blue Ribbon -The Joy Garden at Northside College Preparatory High School Urban Habitat Chicago Silver Ribbon -Eugene Field Park Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration ENCAP, Inc. Green Ribbon -Albany Park Branch Library Public Building Commission of Chicago -Maggie Daley Park Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, Inc and the Chicago Park District 2014 Blue Ribbon -Ping Tom Memorial Park Boathouse Johnson & Lee, site design, ltd., and Chicago Park District Silver Ribbon -Space to Grow: Greening Chicago Schoolyards Chicago Public Schools, Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, and City of Chicago Department of Water Management -Ping Tom Memorial Park Fieldhouse Public Building Commission of Chicago Green Ribbon -WMS Boathouse at Clark Park Studio Gang Architects 2013 Blue Ribbon -The Slotnick Residence Kipnis Architecture + Planning Silver Ribbon -Riverbank Restoration WRD Environmental -Engine Company 16 Public Building Commission of Chicago Green Ribbon -Pilson’s Sustainable Streetscape, Alderman Daniel S. Solis, 25th Ward, and the Chicago Department of Transportation Streetscape and Sustainable Design Program -McGrath Acura Redevelopment Terra Consulting Group, LTD. -

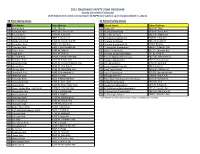

2021 CHILDREN's SAFETY ZONE PROGRAM Zones Currently Enforced

2021 CHILDREN'S SAFETY ZONE PROGRAM Zones Currently Enforced ($35 tickets for vehicles traveling 6-10 MPH over posted speed begins March 1, 2021) 38 Park Safety Zones 22 School Safety Zones Park Name Park Address School Name School Address 1 Abbott Park 49 E. 95th St. 1 Bogan HS 3939 W. 79th 2 Ashmore Park 4807 W Gunnison St 2 Burley Elementary 1630 W. Barry Ave. 3 Beverly Park 2460 W. 102nd St 3 Burr Elementary 1621 W. Wabansia 4 Calumet Park 9801 S. Avenue G 4 Charles Prosser School 2148 N. Long Ave 5 Challenger Park 1100 W. Irving Park Rd 5 Chicago Ag School 3857 W 111th St 6 Columbus Park 500 S. Central Ave 6 Chicago Vocational HS 2100 E 87th St. 7 Douglass Park 1401 S. Sacramento Dr. 7 Christopher Elementary 5042 S. Artesian Ave 8 Foster Park 1440 W. 84th St 8 Dulles Elementary 6311 S. Calumet Ave. 9 Gage Park 2411 W. 55th St 9 Frances Xavier Elementary 751 N. State St 10 Garfield Park 100 N. Central Park Ave. 10 Frazier Magnet Elementary 4027 W. Grenshaw St. 11 Gompers Park 4222 W. Foster Ave 11 Harvard Elementary 7525 S. Harvard Ave 12 Hiawatha Park 8029 W. Forest Preserve Ave. 12 ICCI Elementary 6435 W. Belmont 13 Horan Park 3035 W. Van Buren 13 Jones College Prep HS 700 S State St 14 Horner Park 2741 W. Montrose Ave 14 Lane Tech School 2501 W. Addison St 15 Humboldt Park 1440 N. Humboldt Dr 15 Lorca Elementary 3231 N. Springfield Ave 16 Jefferson Park 4822 N. -

2012 Appropriation Ordinance 10.27.11.Xlsx

2012 Budget Appropriations 3 4 Table of Contents Districtwide 8 Humboldt Park……………...…....………….…… 88 Districtwide Summary 9 Kedvale Park……………...…....………….…….. 90 Communications……………….....….……...….… 10 Kelly (Edward J.) Park……………...…....……91 Community Recreation ……………..……………. 11 Kennicott Park……………...…....………….…… 92 Facilities Management - Specialty Trades……………… 29 Kenwood Community Park……………...…. 93 Grant Park Music Festival………...……….…...… 32 La Follette Park……………...…....………….…… 94 Human Resources…………..…….…………....….. 33 Lake Meadows Park ……………...…....………96 Natural Resources……………….……….……..….. 34 Lakeshore……………...…....………….…….. 97 Park Services - Permit Enforcement 38 Le Claire-Hearst Community Center……… 98 Madero School Park……………...…....……… 99 Central Region 40 McGuane Park……………...…....………….…… 100 Central Region Parks 41 McKinley Park……………………………....…… 103 Central Region – Summary ...……...……................. 43 Moore Park……………...…....………….…….. 105 Central Region – Administration……….................... 44 National Teachers Academy……………...… 106 Altgeld Park………………………………………… 46 Northerly Island……………...…....………….… 108 Anderson Playground Park……….……...………….. 47 Orr Park………………………………..…..…..… 109 Archer Park……...................................................... 48 Piotrowski Park……………...…....………….… 110 Armour Square Park……........................................... 49 Pulaski Park……………...…....………….…….. 113 Augusta Playground……........................................... 50 Seward Park ……………...…....………….…….. 114 Austin Town Hall……...............................................