F6F HELLCAT A6M ZERO-SEN Pacific Theater 1943–44

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

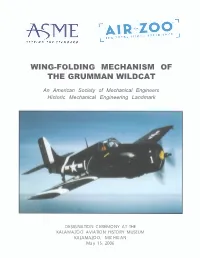

Wing-Folding Mechanism of the Grumman Wildcat

WING-FOLDING MECHANISM OF THE GRUMMAN WILDCAT An American Society of Mechanical Engineers Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark DESIGNATION CEREMONY AT THE KALAMAZOO AVIATION HISTORY MUSEUM KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN May 15, 2006 A Mechanical Engineering Landmark The innovative wing folding mechanism (STO-Wing), developed by Leroy Grumman in early 1941 and first applied to the XF4F-4 Wildcat, manufactured by the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, is designated an ASME Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark. (See Plaque text on page 6) Grumman People Three friends were the principal founders of the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation (Now known as Northrop Grumman Corporation), in January 1930, in a garage in Baldwin, Long Island, New York. (See photo of Leon Swirbul, William Schwendler, and Leroy Grumman on page 7) Leroy Randle (Roy) Grumman (1895-1982) earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from Cornell University in 1916. He then joined the U. S. Navy and earned his pilot’s license in 1918. He was later the Managing Director of Loening Engineering Corporation, but when Loening merged with Keystone Aircraft Corporation, he and two of his friends left Loening and started their own firm — Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation. William T. Schwendler (1904-1978) earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from New York University in 1924. He was reluctant to leave Long Island, so he chose to join Grumman and Swirbul in forming the new company. Leon A. (Jake) Swirbul (1898-1960) studied two years at Cornell University but then left to join the U.S. Marine Corps. Instrumental in the founding and early growth of Grumman, he soon became its president. -

Estudio Del Avión Mitsubishi A6M Zero Y Modelado En CATIA V5

Trabajo Fin de Grado Grado en Ingeniería Aeroespacial Estudio del avión Mitsubishi A6M Zero y modelado en CATIA V5 Autor: Mario Doblado Agüera Tutores: María Gloria del Río Cidoncha Rafael Ortiz Marín Equation Chapter 1 Section 1 Dpto. de Ingeniería Gráfica Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería Universidad de Sevilla Sevilla, 2020 1 Trabajo Fin de Grado Grado en Ingeniería Aeroespacial Estudio del avión Mitsubishi A6M Zero y modelado en CATIA V5 Autor: Mario Doblado Agüera Tutor y publicador: María Gloria del Río Cidoncha Profesor titular Tutor: Rafael Ortiz Marín Profesor colaborador Dpto. de Ingeniería Gráfica Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería Universidad de Sevilla Sevilla, 2020 Trabajo Fin de Grado: Estudio del avión Mitsubishi A6M Zero y modelado en CATIA V5 Autor: Mario Doblado Agüera Tutor y publicador: María Gloria del Río Cidoncha Tutor: Rafael Ortiz Marín El tribunal nombrado para juzgar el Proyecto arriba indicado, compuesto por los siguientes miembros: Presidente: Vocales: Secretario: Acuerdan otorgarle la calificación de: Sevilla, 2020 El Secretario del Tribunal Agradecimientos En primer lugar, quiero agradecer a mis padres el esfuerzo constante que han hecho a lo largo de toda mi vida para que yo esté aquí ahora mismo escribiendo este trabajo, con todo lo que ello implica. Me gustaría darle las gracias también a mi hermano, por guiarme en más de una ocasión. Quiero darle las gracias a todos los amigos que han sido un apoyo para mí en estos años de carrera, como Elena, Jesús, Rocío, Ana…y otros compañeros que me dejo en el tintero. Especialmente, quiero agradecerle a Antonio su ayuda constante en muchos aspectos. -

From the Nisshin to the Musashi the Military Career of Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku by Tal Tovy

Asia: Biographies and Personal Stories, Part II From the Nisshin to the Musashi The Military Career of Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku By Tal Tovy Detail from Shugaku Homma’s painting of Yamamoto, 1943. Source: Wikipedia at http://tinyurl.com/nowc5hg. n the morning of December 7, 1941, Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) aircraft set out on one of the most famous operations in military Ohistory: a surprise air attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawai`i. The attack was devised and fashioned by Admiral Yamamoto, whose entire military career seems to have been leading to this very moment. Yamamoto was a naval officer who appreciated and under- stood the strategic and technological advantages of naval aviation. This essay will explore Yamamoto’s military career in the context of Imperial Japan’s aggressive expansion into Asia beginning in the 1890s and abruptly ending with Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945, to the US and its Allies. Portrait of Yamamoto just prior to the Russo- Japanese War, 1905. Early Career (1904–1922) Source: World War II Database Yamamoto Isoroku was born in 1884 to a samurai family. Early in life, the boy, thanks to at http://tinyurl.com/q2au6z5. missionaries, was exposed to American and Western culture. In 1901, he passed the Impe- rial Naval Academy entrance exams with the objective of becoming a naval officer. Yamamoto genuinely respected the West—an attitude not shared by his academy peers. The IJN was significantly influenced by the British Royal Navy (RN), but for utilitarian reasons: mastery of technology, strategy, and tactics. -

The Wind Rises: a Swirling Controversy

16 The Wind Rises: A Swirling Controversy Sean Mowry ‘16 HST 401: World War II in Cinema Professor Alan Allport In the summer of 2013, Japanese recent history, and its messages are director Hayao Miyazaki released his final important to examine. This is especially the movie as a writer and director, The Wind case in the current context of Japanese Rises.55 Miyazaki is a legend in Japanese desires to remilitarize under its cinema, and is often referred to as the “Walt conservative leadership. 56 Disney of Japan.” He is a founder, and the The Wind Rises tells the story of Jiro most famous member of the Tokyo-based Horikoshi, the real life designer of the animation studio, Studio Ghibli, which has Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane, the produced 5 of the 15 highest grossing most famous airplane in Japanese history 57 anime movies in Japanese history. In fact, and an icon of the Pacific War. The film The Wind Rises takes the tenth spot on that begins in Jiro’s childhood dreams as he list, and it also is the highest grossing flies acrobatically in a plane, but above him 58 Japanese film from 2013. This makes the he sees dark clouds hiding aircraft all influence of this movie very prominent in marked with the Nazi Iron Cross. Jiro’s 55 Roy Akagawa, “Excerpts of Hayao Miyazaki’s 57 “Top Grossing Anime,”Box Office Mojo, News Conference Announcing His Retirement,” Accessed December 16, 2015 The Asahi Shimbun , September 6, 2013 http://www.boxofficemojo.com/genres/chart/?id=a http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/people/A nime.htm J201309060087. -

Design Details of the Mitsubishi Kinsei Engine*

! THE CONDITION of the only conversion figures in the hope that physical engine available for study these figures will best serve the and the data readily available can purposes intended. form the basis for only a very The inspection indicates to the meager report. The study has, writer two possible conclusions however, been an interesting one which are presented herewith: and the results are recorded for what 1. That the group responsible for value they may have. The design the design did a very ingenious job comments are, of necessity, of a of combining what they apparently general nature — much the same as believed to be the most desirable those which would be made on the features of a number of products of preliminary layout of a new design. foreign manufacture — proved For the convenience of many of us features all. These features are built who habitually think in term s of into a composite design of the sort English units, these units are used that “has to work the first time” — even though a large portion of the and probably did. work is apparently based on the 2. That manufacturing methods metric system. As a result, the and equipment of manufacturers numerical data are approximate whose features were appropriated ! "# $ %% & ' () "# # *! "# # +, "# & ' % & ' % "# & % $' % % - % * General description of the engine appeared in “Aviation' s” report on the joint meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineering Detroit Section, and the Engineering Society of Detroit, June 8, 1942, in the article War Production of Aircraft, page 104, July, 1942. This additional material is presented through the courtesy of the SAE. -

Index to the Reminiscences of Vice Admiral Truman

Index to The Reminiscences of Vice Admiral Truman J. Hedding, United States Navy (Retired) Aircraft Carriers Development of tactical doctrine in 1943 for the fast carrier task force, 37-40 See also Carrier Division Three, Task Force 58 Air Force, U.S. Air Force members of the Joint Staff were well organized during the 1949-51 period in terms of the service's party line on various issues, 167-168; some of its responsibilities moved under the Pacific Command when that command became truly joint in the early 1950s, 169-172 Alcohol Cheap whiskey was available at the naval officers' club on Guam in the summer of 1945, 128-129 Ancon, USS (AGC-4) Amphibious command ship that served as a floating hotel in Tokyo for the staff of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey in late 1945, 131-132; Japanese Navy wartime action reports that had been stored in caves were taken aboard the ship in late 1945 to be microfilmed, 139-140. site of 1945 interview of Prince Konoye, former Japanese Prime Minister, 141-142; returned to the United States at the end of 1945, 152-153 Anderson, Major General Orvil A., USA Army Air Forces officer who made inflated claims concerning the effectiveness of his service's bombing campaigns in World War II, 145; role in interrogating Japanese as part of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey in 1945, 146-147 Antiair Warfare Effective U.S. antiaircraft fire during a carrier strike against the Marianas Islands in February 1944, 53 Army, U.S. Some of its responsibilities moved under the Pacific Command when that command became truly joint in the early 1950s, 169-172 Army Air Forces, U.S. -

Additional Historic Information the Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish

USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum Additional Historic Information The Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish AMERICA STRIKES BACK The Doolittle Raid of April 18, 1942 was the first U.S. air raid to strike the Japanese home islands during WWII. The mission is notable in that it was the only operation in which U.S. Army Air Forces bombers were launched from an aircraft carrier into combat. The raid demonstrated how vulnerable the Japanese home islands were to air attack just four months after their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. While the damage inflicted was slight, the raid significantly boosted American morale while setting in motion a chain of Japanese military events that were disastrous for their long-term war effort. Planning & Preparation Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Roosevelt tasked senior U.S. military commanders with finding a suitable response to assuage the public outrage. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a difficult assignment. The Army Air Forces had no bases in Asia close enough to allow their bombers to attack Japan. At the same time, the Navy had no airplanes with the range and munitions capacity to do meaningful damage without risking the few ships left in the Pacific Fleet. In early January of 1942, Captain Francis Low1, a submariner on CNO Admiral Ernest King’s staff, visited Norfolk, VA to review the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, USS Hornet CV-8. During this visit, he realized that Army medium-range bombers might be successfully launched from an aircraft carrier. -

Vought - Wikipedia

10/27/2020 Vought - Wikipedia Vought Vought was the name of several related American aerospace firms. These have included, in the past, Lewis and Vought Corporation, Chance Vought, Vought Vought-Sikorsky, LTV Aerospace (part of Ling-Temco-Vought), Vought Aircraft Companies, and Vought Aircraft Industries. The first incarnation of Vought was established by Chance M. Vought and Birdseye Lewis in 1917. In 1928, it was acquired by United Aircraft and Transport Corporation, which a few years later became United Aircraft Corporation; this was the first of many reorganizations and buyouts. During the 1920s and 1930s, Vought Aircraft and Chance Vought specialized in carrier-based aircraft for the United States Navy, by far its biggest customer. Chance Vought produced thousands of planes during World War II, including the F4U Corsair. Vought became independent again in 1954, and was purchased by Ling- Temco-Vought (LTV) in 1961. The company designed and produced a variety of The VE-7 was the first aircraft to planes and missiles throughout the Cold War. Vought was sold from LTV and owned launch from a U.S. Navy aircraft in various degrees by the Carlyle Group and Northrop Grumman in the early 1990s. It carrier was then fully bought by Carlyle, renamed Vought Aircraft Industries, with Industry Aerospace headquarters in Dallas, Texas. In June 2010, the Carlyle Group sold Vought to the Triumph Group. Founded 1917 Founders Birdseye Lewis Chance M. Vought Contents Key Rex Beisel people History Boone Guyton Chance Vought years 1917–1928 Charles H. Zimmerman 1930s–1960 Parent United Aircraft and LTV acquisition 1960–1990 Transport Corporation 1990s to today (1928-1954) Products Ling-Temco-Vought Aircraft (1962-1992) Unmanned aerial vehicles Missiles Rockets Workshare projects References External links History Chance Vought years 1917–1928 The Lewis and Vought Corporation was founded in 1917 and was soon succeeded by the Chance Vought Corporation in 1922 when Birdseye Lewis retired. -

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection Kristine L. Kaske; revised 2008 by Melissa A. N. Keiser 2003 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Black and White Negatives....................................................................... 4 Series 2: Color Transparencies.............................................................................. 62 Series 3: Glass Plate Negatives............................................................................ 84 Series : Medium-Format Black-and-White and Color Film, circa 1950-1965.......... 93 -

85-AF-68 Kawasaki Ki-100

A/C SERIAL NO.BAPC.83 SECTION 2B INDIVIDUAL HISTORY KAWASAKI Ki-100-1b BAPC.83/8476M MUSEUM ACCESSION NUMBER 85/AF/68 1945 Assembled at Kawasaki’s’ Kagamigahara factory in the last week of June 1945 as a KI-100 Otsu; production for the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force ceased in August 1945, totalling some 390 aircraft. Constructors’ number 16336. Other than having an all-round vision canopy, the -1b airframe was identical to the Kawasaki Ki-61-11 Hien (Tony) with a Mitsubishi 1,500 h.p.14 cylinder radial engine replacing the Kawasaki liquid cooled in-line engine, of which there was a shortage. Most of the 118 Ki100-1b aircraft completed were assigned to the defence of the Japanese home islands. Giuseppe Picarella’s research suggests the aircraft when new was initially sent to the Kagamigahara Army Depot and accepted into the IJAAF during the first two weeks of July 1945. Aug 45 Originally thought to have been captured by American forces occupying Japan from 28th August - the origin and early history of the Museum’s aircraft was unclear for many years, although the US military authorities did allocate a number of aircraft surrendered in Japan for RAF use in Oct/Nov 45. However, research by Giuseppe Picarella (Aeroplane February 2006 pp.70 – 75) seems to have confirmed this airframe’s origins. It appears to have been one of the 24 aircraft found at Tan Son Nhut (Saigon) airfield in what was then French Indo-China, and was in serviceable condition. Japanese ferry pilot Sergeant Y.