Catwalk Copycats: Why Congress Should Adopt a Modified Version of the Design Piracy Prohibition Act, 14 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands

November 9, 2016 Xcel Brands, Inc. Quick Time Response (QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands NEW YORK, Nov. 09, 2016 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Xcel Brands, Inc. (NASDAQ:XELB) is pleased to announce multiple new licenses across its owned brands as licensees look to pursue growth in categories complementary to Xcel's successful quick time response (QTR) apparel programs at Lord & Taylor and Hudson's Bay stores. CEO and Chairman of Xcel Brands, Inc. Robert W. D'Loren remarked, "With the rise of a ‘see-now-buy-now' consumer shopping mentality and the need to respond to trends as they happen, Xcel created an innovative solution to bring exclusive brands to our department store partners in a quick time response format. The rapid growth of these apparel programs has generated excitement within the licensing community across numerous complementary categories. With these new partnerships we will continue to build meaningful lifestyle brands under the IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi and H Halston labels." New licensees under the Isaac Mizrahi brand include tech accessories and luggage, with product set to retail in Spring 2017. Xcel Brands, Inc. entered into a licensing agreement with Bytech NY Inc. for tech accessories for smartphones, PCs, tablets, and personal audio across the Isaac Mizrahi New York, IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi, and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. Xcel also entered into a licensing agreement with Longlat Inc. for a collection of hard and soft luggage under the Isaac Mizrahi New York and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. New licensees under the H Halston brand include sleepwear and intimates, legwear and slippers, and non-optical sunglasses and readers. -

Calm Down NEW YORK — East Met West at Tiffany on Sunday Morning in a Smart, Chic Collection by Behnaz Sarafpour

WINSTON MINES GROWTH/10 GUCCI’S GIANNINI TALKS TEAM/22 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaper • September 13, 2004 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Calm Down NEW YORK — East met West at Tiffany on Sunday morning in a smart, chic collection by Behnaz Sarafpour. And in the midst of the cross-cultural current inspired by the designer’s recent trip to Japan, she gave ample play to the new calm percolating through fashion, one likely to gain momentum as the season progresses. Here, Sarafpour’s sleek dress secured with an obi sash. For more on the season, see pages 12 to 18. Hip-Hop’s Rising Heat: As Firms Chase Deals, Is Rocawear in Play? By Lauren DeCarlo NEW YORK — The bling-bling world of hip- hop is clearly more than a flash in the pan, with more conglomerates than ever eager to get a piece of it. The latest brand J.Lo Plans Show for Sweetface, Sells $15,000 Of Fragrance at Macy’s Appearance. Page 2. said to be entertaining suitors is none other than one that helped pioneer the sector: Rocawear. Sources said Rocawear may be ready to consider offers for a sale of the company, which is said to generate more than $125 million in wholesale volume. See Rocawear, Page4 PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDMONDAY J.Lo Talks Scents, Shows at Macy’s Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear By Julie Naughton and Pete Born FASHION The spring collections kicked into high gear over the weekend with shows Jennifer Lopez in Jennifer Lopez in from Behnaz Sarafpour, DKNY, Baby Phat and Zac Posen. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Jewish-And-Asian-Pacific-Heritage

In May 2021, We celebrated Jewish American and Asian American Heritage! Click the buttons to the right to explore more about Jewish American and Asian Pacific American history. Today, America is home to around 7 million Jewish Americans. Click the buttons below for more! Click the button below to return to the main menu Learn Jewish Americans may identify as Jewish based on religion, ethnic upbringing, or both. The Jewish population in America is diverse and includes all races and ethnicities. Did you know? • Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, one of the most famous Jewish athletes in American sports, made national headlines when he refused to pitch in the first game of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur. • Hanukkah is not the most popular holiday in Jewish heritage. Passover is the most celebrated of all Jewish holidays with more than 70% of Jewish Americans taking part in a seder, its ritual meal. Hanukkah may be the best known Jewish holiday in the United States. But despite its popularity in the U.S., Hanukkah is ranked one of Judaism’s minor festivals, and nowhere else does it garner such attention. The holiday is mostly a domestic celebration, although special holiday prayers also expand synagogue worship. Explore Hanukkah The Menorah Hanukkah may be the most well The Hanukkah menorah (or chanukiah) is known Jewish holiday in the United a nine-branched candelabrum lit during the States. But despite its popularity in eight-day holiday of Hanukkah, as opposed the U.S., Hanukkah is ranked one to the seven-branched menorah used in of Judaism’s minor festivals, and the ancient Temple or as a symbol. -

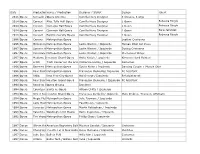

Date Production Name Venue / Production Designer / Stylist Design

Date ProductionVenue Name / Production Designer / Stylist Design Talent 2015 Opera Komachi atOpera Sekidrera America Camilla Huey Designer 3 dresses, 3 wigs 2014 Opera Concert Alice Tully Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Sara Jakubiak 2013 Opera Concert Bard University Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 1996 Opera Carmen Metropolitan Opera Leather Costumes 1996 Opera Midsummer'sMetropolitan Night's Dream Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Human Pillar Set Piece 1997 Opera Samson & MetropolitanDelilah Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Dyeing Costumes 1997 Opera Cerentola Metropolitan Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Mechanical Wings 1997 Opera Madame ButterflyHouston Grand Opera Anita Yavich / Izquierdo Kimonos Hand Painted 1997 Opera Lillith Tisch Center for the Arts OperaCatherine Heraty / Izquierdo Costumes 1996 Opera Bartered BrideMetropolitan Opera Sylvia Nolan / Izquierdo Dancing Couple + Muscle Shirt 1996 Opera Four SaintsMetropolitan In Three Acts Opera Francesco Clemente/ Izquierdo FC Asssitant 1996 Opera Atilla New York City Opera Hal George / Izquierdo Refurbishment 1995 Opera Four SaintsHouston In Three Grand Acts Opera Francesco Clemente / Izquierdo FC Assistant 1994 Opera Requiem VariationsOpera Omaha Izquierdo 1994 Opera Countess MaritzaSanta Fe Opera Allison Chitty / Izquierdo 1994 Opera Street SceneHouston Grand Opera Francesca Zambello/ Izquierdo -

Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign Im Film: Eine Erste Bibliographie 2011

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff; Ludger Kaczmarek Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie 2011 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Kaczmarek, Ludger: Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2011 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 122). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0122_11.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 122, 2011: Mode im Film. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Ludger Kaczmarek, Hans J. Wulff. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0122_11.html Letzte Änderung: 20.2.2011. Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Zusammengest. v. Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek Inhalt: da, wo die Hobos sind, er riecht wie einer: Also ist er Einleitung einer. Warum sollte man jemanden für einen anderen Bibliographien halten als den, der er zu sein scheint? In Nichols’ Direktoria Working Girl (1988) nimmt eine Sekretärin heimlich Texte für eine Zeit die Rolle ihrer Chefin an, und sie be- nutzt auch deren Garderobe und deren Parfüm. -

NYC Fashion Giants Featured in Exhibit Curated by Two Israelis | the Times of Israel

9/18/2019 NYC fashion giants featured in exhibit curated by two Israelis | The Times of Israel RUNWAY STORY NYC fashion giants featured in exhibit curated by two Israelis ‘New York Fashion Rediscovered’ spotlights treasure trove of photographs of designers and supermodels discovered on a New York City sidewalk By JESSICA STEINBERG Today, 3:55 pm Fashion models and their muses at 'New York Fashion Rediscovered,' a new exhibit created by two Israelis in New York City's Time Square, just in time for 2019 Fashion Week (Courtesy ZAZ10TS) It took two Israelis in New York City — one gallery owner and one curator — to put together an exhibit of historic fashion photographs that had been discovered on a city sidewalk. The exhibit, “New York Fashion Rediscovered 1982-1997,” opened September 5, at 10 Times Square, coinciding with New York Fashion Week. The exhibit brings to life a vivid period in the New York City fashion industry, when designers began creating high- end day and evening wear, as well as power dressing for women in the workforce. Fashion designers and supermodels achieved celebrity status, and the celebrated moments of the runway shows were their finales, when designers would walk down the runway, arm-in-arm with the leading supermodels of the day. Those joyous moments are what was preserved in the fashion-loving photographs of the collection. The fashion stars featured in the photographs included designers Anna Sui, Donna Karan, Liz Claiborne, Ralph Lauren, Marc Jacobs, Perry Ellis, Isaac Mizrahi, Alber Elbaz, Anne Klein, Geoffrey Beene, Rebecca Moses, BCBG Max Azria, Linda Allard for Ellen Tracy, Adrienne Vittadini, and Gemma Kahng, and models Kate Moss, Cindy Crawford, https://www.timesofisrael.com/nyc-fashion-giants-featured-in-historic-exhibit-curated-by-two-israelis/ 1/3 9/18/2019 NYC fashion giants featured in exhibit curated by two Israelis | The Times of Israel Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, Helena Christensen, and Kristen McMenamy. -

Xcel Brands Inc., an Innovator in Fashion Brand Development and Omnichannel Retail, Selects NGC’S Global Enterprise Suite

Xcel Brands Inc., an Innovator in Fashion Brand Development and Omnichannel Retail, Selects NGC’s Global Enterprise Suite Xcel Brands Inc. owns and manages leading fashion brands such as Isaac Mizrahi, Judith Ripka, H Halston, and C. Wonder MIAMI, FL — April 26, 2016 — NGC Software today announced Xcel Brands has selected NGC’s Global Enterprise Suite, a fully integrated suite including fashion PLM, apparel ERP and Supply Chain Management. Headquartered in New York City, Xcel Brands is a leader and innovator in the acquisition, design, production, licensing, marketing and retail sales of consumer brands. Xcel owns and manages the Isaac Mizrahi, Judith Ripka, H Halston and C. Wonder brands. NGC's Global Enterprise Suite (GES) brings together NGC's solutions for apparel ERP, fashion PLM and SCM in a fully integrated suite. All parts of the system work in unison, and information is shared seamlessly throughout the suite with a common platform – eliminating the redundancies found with other systems and improving workflows, productivity and speed to market. “Xcel Brands is an innovative, forward-thinking company with a dynamic vision for the fashion industry – exactly the kind of company that NGC loves to partner with,” said Mark Burstein, president of sales, marketing and R&D, NGC Software. “We’re honored Xcel Brands selected NGC to deliver a strategic software platform for their business.” About Xcel Brands Xcel Brands, Inc. (NASDAQ:XELB) is a brand development and media company engaged in the design, production, licensing, marketing and direct-to-consumer sales of branded apparel, footwear, accessories, jewelry, home goods, and other consumer products, and the acquisition of dynamic consumer lifestyle brands. -

Xcel Brands, Inc. Announces Licensing Deal with Synclaire Brands

February 6, 2013 Xcel Brands, Inc. Announces Licensing Deal With Synclaire Brands NEW YORK, Feb. 6, 2013 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Xcel Brands, Inc. (OTCQB:XELB) has signed an exclusive licensing agreement with Synclaire Brands. This agreement will give Synclaire Brands the license to manufacture and distribute children's footwear for the Isaac Mizrahi New York brand. The collection will be available at retail in Fall 2013. Robert D'Loren, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Xcel Brands, Inc., said, "I am very excited to partner with Synclaire on this great line of children's footwear. This additional category complements our children's clothing collection. The Isaac Mizrahi brand brings an exciting point of view to children's accessories." Evan Cagner, President, Synclaire Brands, said, "We are thrilled to be working with Xcel Brands and Isaac Mizrahi on this new line of children's footwear. The line will capture the designer's iconic colorful aesthetic." Xcel Brands, Inc. engages in the acquisition, design, licensing and marketing of consumer brands incorporating an OMNICHANNEL sales strategy inclusive of interactive media, digital and bricks and mortar retail. In 2011, the company acquired designer apparel brand Isaac Mizrahi New York and an interest in Liz Claiborne New York, quickly expanding into 100+ categories for the Isaac Mizrahi brand. The company's executive management team possesses significant talent, experience and a proven track record of success to create and grow branded consumer products businesses. www.xcelbrands.com. Isaac Mizrahi has been a leader in the fashion industry for almost 30 years. Since his first collection in 1987, Mr. -

Machine Learning (Ml) for Tracking the Geo-Temporality of a Trend: Documenting the Frequency of the Baseball-Trucker Hat on Social Media and the Runway

MACHINE LEARNING (ML) FOR TRACKING THE GEO-TEMPORALITY OF A TREND: DOCUMENTING THE FREQUENCY OF THE BASEBALL-TRUCKER HAT ON SOCIAL MEDIA AND THE RUNWAY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Rachel Rose Getman May 2019 © 2019 Rachel Rose Getman ABSTRACT This study applied fine-grained Machine Learning (ML) to document the frequency of baseball-trucker hats on social media with images populated from the Matzen et al. (2017) StreetStyle-27k Instagram dataset (2013-2016) and as produced in runway shows for the luxury market with images populated from the Vogue Runway database (2000-2018). The results show a low frequency of baseball-trucker hats on social media from 2013-2016 with little annual fluctuation. The Vogue Runway plots showed that baseball-hats appeared on the runway before 2008 with a slow but steady annual increase from 2008 through 2018 with a spike in 2016 to 2017. The trend is discussed within the context of social, cultural, and economic factors. Although ML requires refinement, its use as a tool to document and analyze increasingly complex trends is promising for scholars. The study shows one implementation of high-level concept recognition to map the geo-temporality of a fashion trend. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Rachel R. Getman holds a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). Her interests lie in the intersection of arts and sciences through interdisciplinary collaboration. The diversification of her professional experience from the service industry, education, wardrobe styling, apparel production, commercial vocals, and organic agriculture influence her advocacy for holistic thinking and non-linear problem solving. -

Fashion Icon/Singer Isaac Mizrahi Returns to Café Carlyle with an All-New Show, February 5-16, 2019

For Immediate Release October 15, 2018 FASHION ICON/SINGER ISAAC MIZRAHI RETURNS TO CAFÉ CARLYLE WITH AN ALL-NEW SHOW, FEBRUARY 5-16, 2019 Isaac Mizrahi returns to Café Carlyle with an all-new show, Isaac Mizrahi: Queen Size, February 5 – 16. His previous two residencies in the room were sellouts, receiving widespread critical acclaim. Mizrahi will perform classics by Leonard Bernstein, Cat Stevens, Jimmy Webb, John Kander, Cole Porter, James Taylor and Jerome Kern. Once again, he’ll be joined by his band of (handsome, thin, single) (maybe not single) jazz musicians, led by Ben Waltzer. With all-new stories and observations, Mizrahi will also have a fresh stock of swag items to re- gift to audience members. No topics will be off-limits: politics, sex, prescription drugs, millennials. In a review of his Café debut, The New York Times noted “he is determined to challenge the cultural status quo and help blaze a path into a more liberated future… his Café Carlyle engagement is a big deal.” Vogue called his previous Café residency, “the hottest ticket at New York Fashion Week.” 321 DEAN STREET, #5 BROOKLYN, NY 11217 p 718.643.9052 www.blakezidell.com Performances will take place Tuesday – Saturday at 8:45pm. Weekday pricing begins at $85 per person / Bar Seating: $65 / Premium Seating: $135. Weekend pricing begins at $100 per person / Bar Seating: $80 / Premium Seating: $150. A Special Valentine’s Day show includes a four-course prix fixe dinner with table seating - General Seating: $265 per person / Premium Seating: $315 / Bar Seating: $80. Reservations can be made by phone at 212.744.1600 or online via Ticketweb. -

Xcel Brands Annual Report 2020

XCel Brands Annual Report 2020 Form 10-K (NASDAQ:XELB) Published: April 14th, 2020 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: December 31, 2019 Commission File Number: 001‑37527 OR ◻ TRANSITION REPORT UNDER SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 XCEL BRANDS, INC. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 76‑0307819 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 1333 Broadway, 10th Floor, New York, NY 10018 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (347) 727‑2474 (Issuer’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Exchange Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.001 par value per share XELB NASDAQ Global Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Exchange Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ◻ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ◻ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act 1934 during the past 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.