Gaskin-Complaint.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

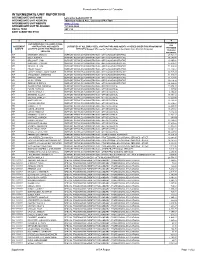

Intermediate Unit Reporting

Pennsylvania Department of Education INTERMEDIATE UNIT REPORTING INTERMEDIATE UNIT NAME Lancaster-Lebanon IU 13 INTERMEDIATE UNIT ADDRESS 1020 New Holland Ave., Lancaster PA 17601 INTERMEDIATE UNIT WEBSITE www.iu13.org INTERMEDIATE UNIT TELEPHONE 717-606-1600 FISCAL YEAR 2011-12 DATE SUBMITTED BY IU 2 4 4 4 REMUNERAT LIST INDIVIDUALLY ALL EMPLOYEES, ION AGREEMENT CONTRACTORS AND AGENTS LIST DUTIES OF ALL EMPLOYEES, CONTRACTORS AND AGENTS COVERED UNDER THIS PROGRAM OR PROVIDED NUMBER COVERED UNDER THIS PROGRAM OR SERVICES (Suggest IU's use the Function/Object description from Chart of Accounts) TO EACH SERVICES INDIVIDUAL 954 BARNHART, BRIAN D SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 27,721.14 954 BILLY, SUSAN A SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 38,546.40 954 BRILLHART, GINA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 13,695.84 954 BURKHART, CYNTHIA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 35,839.01 954 FIGURELLE, LISA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 71,929.68 954 FINLEY, MOLLY SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 118,130.64 954 JANNEY SCHALL, DIANE MARIE SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 34,727.28 954 SKRODINSKY, CHRISTINE SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 51,545.33 954 SPINNER, ANN SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 16,728.48 954 WILEY, DEBRA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 39,116.16 954 ZUBECK, SHERRY D SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION -

Proposed Joint Petition to Stay 2020 Upset Sales

IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS OF LANCASTER COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA CIVIL ACTION - LAW IN RE: Lancaster County Tax Claim : Bureau Upset Tax Sales to be held on : No. September 21, 2020 : JOINT PETITION TO STAY 2020 UPSET TAX SALES PURSUANT TO 72 P.S. §5860.601(c) 1. Petitioners are the Treasurer of the County of Lancaster, Pennsylvania and the below identified taxing authorities of the political subdivisions within Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (hereinafter collectively referred to as “Petitioners”); specifically: Adamstown Borough, Akron Borough, Bart Township, Brecknock Township, Caernarvon Township, Christiana Borough, Clay Township, East Cocalico Township, West Cocalico Township, Colerain Township, Columbia Borough, Conestoga Township, Conoy Township, Denver Borough, East Donegal Township, West Donegal Township, Drumore Township, East Drumore Township, Earl Township, East Earl Township, West Earl Township, East Petersburg Borough, Eden Township, Elizabeth Township, Elizabethtown Borough, Ephrata Borough, Fulton Township, East Hempfield Township, West Hempfield Township, East Lampeter Township, West Lampeter Township, Lancaster City, Lancaster Township, Leacock Township, Upper Leacock Township, Lititz Borough, Little Britain Township, Manheim Township, Manheim Borough, Manor Township, Marietta Borough, Martic Township, Millersville Borough, Mount Joy Borough, Mount Joy Township, Mountville Borough, New Holland Borough, Paradise Township, Penn Township, Pequea Township, Providence Township, Quarryville Borough, Rapho Township, Sadsbury -

Social Studies Innovations 1968-1969; a Report of the Social

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 040 899 95 SO 000 112 AUTHOR Myers, Charles B, TITLE Social Studies Innovations 1968-1969;A Report of the Social Studies Pilots of theSPEEDIER Project. INSTITUTION Curriculum Study Research and Development Councilof South Central Pennsylvania, Palmyra. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW) , Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 69 GRIAT OEG-3-7-703596-4396 NOTE 67p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC$3.45 DESCRIPTORS Articulation (Program), Curriculum Development, Curriculum Evaluation, *DemonstrationProjects, Diffusion, *Educational Strategies,Information Dissemination, *Inservice Teacher Education, *Instructional Innovation, Models, PilotProjects, *Social Studies, Teaching Techniques ABSTRACT Five pilot programs were selectedas vehicles to introduce flill social studies curriculumideas into the 52 school systems served by the project. The objectivesof this ESEli Title III project were:1) to improve social studies instructionand teacher classroom behavior; 2) to increase local educatorunderstanding of the new curriculum; 3)to develop teacher skills in usingnew strategies and materials; 4) to develop positiveattitudes, educator skills, and knowledge for curriculumexperimentation and change; 5) to modify district procedures and policiesto promote change. The Fenton Social Science Program and the GreaterCleveland Social Science Program were used in secondary grades.The University of Minnesota Project Social Studies Program, TabaSocial Studies Curriculum, Senesh Social ScienceProgram (Our Working World), and the Cleveland Program were used in theelementary grades. Each of these programs and the over-all Pilot Modelare described in terms of pilot preparation, implementation, dissemination,and critical evaluation. To determine thesuccess of the pilots, limited assessment procedures were used tomeasure student critical thinking ability, inquiry skills, valueor attitude change, and academic achievement, and to measure teacher values,beliefs and self-concept. -

Adult Education Catalog 2021-2022

Lancaster County Career & Technology Center Adult Education Catalog 2021-2022 YOUR FUTURE. YOUR CAREER. OUR PRIORITY. Mission The Mission of the LCCTC is to prepare people for skilled, innovative, and productive careers. Our Vision The Lancaster County Career & Technology Center is a full service career and technical school dedicated to preparing high school students and adults for careers in the new economy. LCCTC is best among its class and strives to meet the highest standards of quality instruction. Lancaster County Career & Technology Center 1730 Hans Herr Drive Willow Street, PA 17584 Revised May, 2021 Table of Contents SECTION 1: Institutional Information ......................................................................................................................5 Additions and Revisions .........................................................................................................................................5 Joint Operating Committee ....................................................................................................................................6 Superintendent of Record ......................................................................................................................................6 Lancaster County CTC Administration ....................................................................................................................6 Campus Locations ..................................................................................................................................................7 -

Class of 2023 and Beyond Cocalico High School Educational Planning Guide 2021-2022

Class of 2023 and Beyond Cocalico High School Educational Planning Guide 2021-2022 This Educational Planning Guide is intendedCocalico to provide High students School and their parents with information about the educational program, graduation requirements, and courses of study at Cocalico High School. Planning your program for four yearsEducational of high school Planning requires self-appraisal Guide with regard to your capabilities, interests, and goals. A familiarity with the various2013-2014 courses of study and a knowledge of the required courses are needed for sufficient progression in the educational process. Serious consideration should be given to your selection of courses which will be consistent with your chosen pathway,This aptitudes, Educational interests, Planning abilities, Guide isand intended post-high to provide school students plans. and their parents with information about the educational program, graduation requirements, and courses of study at Cocalico High School. Cocalico High School will make a serious attempt to schedule you for all of the courses you desire. Please note that in somePlanning cases your enrollment program forchanges four years and of staffing high school needs requires may self-appraisaldictate the cancellation with regard to of your certain capabilities, elective courses interests, and goals. A familiarity with the various courses of study and a knowledge of the required courses are and advancedneeded for courses. sufficient It is,progression therefore, in importantthe educational to consider process. alternate options when planning your selection of courses. StudentsSerious consideration and parents should are invited be given to to consult your selection with teachersof courses and which counselors will be consistent for assistance with your in chosenplanning their program.pathway, Parents aptitudes, may make interests, appointments abilities, and with post-high counselors school plans. -

Lancaster County Tax Claim : Bureau Upset Tax Sales to Be Held on : No

IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS OF LANCASTER COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA CIVIL ACTION - LAW IN RE: Lancaster County Tax Claim : Bureau Upset Tax Sales to be held on : No. September 21, 2020 : JOINT PETITION TO STAY 2020 UPSET TAX SALES PURSUANT TO 72 P.S. §5860.601(c) 1. Petitioners are the Treasurer of the County of Lancaster, Pennsylvania and the below identified taxing authorities of the political subdivisions within Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (hereinafter collectively referred to as “Petitioners”); specifically: Adamstown Borough, Akron Borough, Bart Township, Brecknock Township, Caernarvon Township, Christiana Borough, Clay Township, East Cocalico Township, West Cocalico Township, Colerain Township, Columbia Borough, Conestoga Township, Conoy Township, Denver Borough, East Donegal Township, West Donegal Township, Drumore Township, East Drumore Township, Earl Township, East Earl Township, West Earl Township, East Petersburg Borough, Eden Township, Elizabeth Township, Elizabethtown Borough, Ephrata Borough, Fulton Township, East Hempfield Township, West Hempfield Township, East Lampeter Township, West Lampeter Township, Lancaster City, Lancaster Township, Leacock Township, Upper Leacock Township, Lititz Borough, Little Britain Township, Manheim Township, Manheim Borough, Manor Township, Marietta Borough, Martic Township, Millersville Borough, Mount Joy Borough, Mount Joy Township, Mountville Borough, New Holland Borough, Paradise Township, Penn Township, Pequea Township, Providence Township, Quarryville Borough, Rapho Township, Sadsbury -

In Respect to C=Iculum Type and High School Education, Postsecondary Education, and Work Experience for Lancaster and Lebanon Counties in Pennsylvania

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 337 643 CE 059 294 AUTHOR Lucas, Michael A. TITLE Comparative Analysis of High School Graduates in Central Pennsylvania from Vocational, Academic and General Curricula for the Years 1982, 1985 and 1988 for Lancaster and Lebanon Counties. INSTITUTICN Lancaster County Vocational-Technical Schools, Pa. SPONS AGENCY Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education, Harrisburg. Bureau of Vocational and Adult Education. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 50p. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Education; Educational Improvement; Employment Patterns; Females; *General Education; Graduate Surveys; *High School Graduates; High Schools; Males; *Outcomes of Education; Postsecondary Education; Program Improvement; *Vocational Education; Wages IDENTIFIERS *Pennsylvania (Lancaster County); *Pennsylvania (Lebanon County) ABSTRACT A study compared the records of high school graduates in respect to c=iculum type and high school education, postsecondary education, and work experience for Lancaster and Lebanon Counties in Pennsylvania. Data were collected through questionnaires mailed to all graduates from the years 1982, 1985, and 1988 and from high s- lol transcripts. The study involved a total population of 15,24E 'rom which 32 percent responded. Some of the results of the survey were as follows: (1) more than 85 percent of the respondents are either working full time or are enrolled in postsecondary education; (2) academic and vocational graduates who are employed receive a weekly salary $20 greater than general curriculum graduates; and (3) most respondents who had attended vocational programs were satisfied with them, although some wanted to see improvements in curriculum. The following recommendations were made: (1) academic and vocational curricula should be more integrated; (2) recruiting for academic and vocational programs should continue; (3) the special needs population must be considered; and ;4) general curriculum students should ne directed toward vocational or academic programs. -

2019 PURTA Properties

parcel_number status owner address1 address2 city state_code zip_code land_use school district municipality assessed_value 0101463900000 ACTIVE DENVER & EPHRATA TELEPHONE C 130 E MAIN ST EPHRATA PA 17522 TELEPHONE&TELEGRAPH COCALICO SCHOOL DISTRICT ADAMSTOWN BORO 71600 0208075000000 ACTIVE DENVER & EPHRATA TELEPHONE C 130 E MAIN ST EPHRATA PA 17522 TELEPHONE&TELEGRAPH EPHRATA AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT AKRON BORO 162100 0301296700000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 50400 0303171300000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 TRANS/UTILITY VACANT SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 90400 0304136600000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 6400 0304326300000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 104000 0304375100000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 TRANS/UTILITY VACANT SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 77000 0304721400000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 105000 0304939100000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 99800 0304939800000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 112000 0305093400000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 -

SCHOOL REPORT Cocalico Senior High School Denver, Pennsylvania

SCHOOL REPORT Cocalico Senior High School Denver, Pennsylvania P | r| e | s| e | n | t | e | d | | b | y Jack Fry REALTOR® Pennsylvania Real Estate License: RM028607-C W| o| rk| : | | ( | 610| ) | | 670| - | 2770 M| a| i| n| : | | I| n| fo| @| g| o| b| e| rk| sc | o| u| n| t | y | . | c | o| m RE/MAX of Reading 1290 | | B | r| o | a | d | c| a | s| t | i | n | g | | R| o | a | d W| y| o | m | i | s| s| i | n | g, | P | A | | 19610 Copyright 2020 Realtors Property Resource® LLC. All Rights Reserved. Information is not guaranteed. Equal Housing Opportunity. 7/8/2020 Cocalico Senior High School School: Cocalico Senior High School School Details School Facts Cocalico Senior High School Cocalico School District Name Cocalico Senior High Overall Grade School Level Total Enrollment 998 3,047 High Students per Teacher 14:1 14:1 Type Students in Free Lunch Program 30% 32% Public Grades Served Academic Grade 9-12 School District Average GPA 3.53 (out of 600 responses) 3.53 (out of 600 responses) Cocalico School District Math Proficiency 89% 53% Address 810 S 4Th St, Denver, PA Reading Proficiency 88% 77% 17517 Gifted Students 2% – Phone AP Enrollments 105 – (717) 336-1423 Graduation Rate 93% 93% Average ACT Score 27 (out of 21 responses) 27 (out of 21 responses) Average SAT Score 1,150 (out of 268 responses) 1,150 (out of 268 responses) Teacher Grade Average Teacher Salary $72,219 $72,219 Teachers in 1st or 2nd Year 4% 6% About this data: Facts and proficiency scores are provided by Niche, which compiles scores, community reviews and other data about schools across the United States. -

Assistance for Students and Families Without Home Internet April 2020

Assistance for Students and Families without Home Internet April 2020 The Steinman Foundation and Lancaster STEM Alliance have partnered with Lancaster-Lebanon Intermediate Unit 13 (IU13), school district Technology Coordinators, Comcast and other Internet providers to offer home Internet assistance at no cost for up to six months! DON’T LET YOUR CHILDREN FALL BEHIND ACADEMICALLY BECAUSE THEY CAN’T ATTEND SCHOOL ONLINE! Here’s how you can apply: Step 1: If you live in an area served by Comcast, sign up for the Internet Essentials program before June 30, 2020. You can do this today at InternetEssentials.com or by calling 855-846-8376. If you are eligible for this program, you will receive six months of free broadband Internet plus an additional six months of Internet for $9.95 a month! This will give you a full year of broadband Internet for under $60. Families in Columbia School District, the School District of Lancaster, La Academia Partnership Charter School, Leola Elementary School, Donegal Intermediate School and Lampeter Elementary School automatically meet income guidelines. Step 2: If, for any reason, you do not qualify for the Internet Essentials program, contact your local school district Technology Coordinator who has funds to help you find another Internet solution. Names and contact numbers are included on the back of this flyer. Please keep documentation that you have been rejected for the Internet Essentials program or that you live in an area not served by Comcast. MAKE SURE YOUR CHILDREN HAVE THE TOOLS THEY NEED TO LEARN -

School Board Minutes

UPPER ST CLAIR SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF SCHOOL DIRECTORS Mr. Patrick A. Hewitt, President • Mr. Phillip J. Elias, Vice President • Mrs. Amy L Billerbeck Mrs. Barbara L. Bolas • Mrs. Jennifer L. Bowen • Dr. Daphna Gans • Mr. Louis P. Mafrice, Jr. Mrs. Angela B. Petersen • Mrs. Jennifer A. Schnore Dr. John T. Rozzo, Superintendent • Mrs. Jocelyn P. Kramer, Solicitor SCHOOL BOARD MEETING MINUTES Monday, January 25, 2021 @ 7:00pm Executive Session @ 6:00pm (Personnel and Legal Matters) District Administration Building Board Room Notice having been advertised and posted and members duly notified, a Board Meeting of the Board of School Directors was held on January 25, 2021 in the District Administration Room. School Board Members in Attendance: Mr. Phillip J. Elias, Vice President (in-person) Mrs. Amy Billerbeck (virtual) Mrs. Barbara L. Bolas (in-person) Mrs. Jennifer L. Bowen (virtual) Dr. Daphna Gans (virtual) Mr. Louis P. Mafrice Jr. (virtual) Mrs. Angela Petersen (in-person) Mrs. Jennifer Schnore (virtual) School Personnel in Attendance: Dr. John T. Rozzo, Superintendent (in-person) Dr. Sharon K. Suritsky, Assistant/Deputy Superintendent (virtual) Mrs. Amy Pfender, Assistant to the Superintendent (in-person) Mr. Ray Carson, Senior Director of Operations & Administrative Services (in-person) Mr. Scott Burchill, Director of Business & Finance (in-person) Dr. Lou Angelo, Director of Facilities and Operations (virtual) Mr. Raymond Berrott, Director of Technology (in-person) Dr. Judith Bulazo, Director of Curriculum and Development (virtual) Mrs. Cassandra Doggrell, Director of Student Support Services (virtual) Mrs. Lauren Madia, Assistant Director of Student Support Services (in-person) Mr. Bradley Wilson, Director of Strategic Initiatives (virtual) Mrs. -

AFCLL Academy Charter Schools

AFCLL Academy Charter Schools EDUCATION THROUGH ATHLETICS Afclancasterlions.org Application to Pennsylvania Department of Education On behalf AFC Lancaster Lions 81 Longfellow Dr. Lancaster PA 17602 www.afclancasterlions.org pg. 1 Table of Contents INFO SHEET ................................................................................................................................................... 6 I. SCHOOL DESIGN ...................................................................................................................................... 10 1.MISSION STATEMENT .......................................................................................................................... 10 A. CORE PHILOSOPHY AND PURPOSE ................................................................................................. 10 B. KEY DESIGN ELEMENTS ................................................................................................................... 11 2. MEASURABLE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................. 18 A. MEASURABLE ACADEMIC GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ....................................................................... 18 B. MEASURABLE NON-ACADEMIC GOALS ........................................................................................... 20 3. EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM ................................................................................................................... 21 A. EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM ..............................................................................................................