Transcript of the Spoken Word, Rather Than Written Prose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

The Antelope Special Edition

page1 9/7/05 12:07 AM Page 1 (Cyan plate) The Antelope Special Edition Awareness news: Pages 4-7 Hurricane Katrina: Pages 8-9 Summer features: Pages 10-12 Loper sports: Pages 13-15 Vol. 2, No. 1 Sept. 8, 2005 page16 9/7/05 1:34 AM Page 1 (Cyan plate) 1200 Minutes $3999 Try to find a better deal. Plus, Add A Line for just $9.95 more. Up to 3 lines. New activation and 2-year service agreement required. LG-3200 $19 95 FREE BUY 1 FOR $19.99 GET 3 FREE NO REBATES NEEDED With 2-year agreement. 15-DAY SATISFACTION GUARANTEE To take advantage of these great deals, come by your local Cellular One store listed below. Promotional Offer: $9.95 additional line offer is available for a limited time when added to Local calling plans $40.00 or high er, and is subject to change without notice. New activation and 2-year service agreement required. $16.95 additional line offer is available for a limited time when added to 21-state Home and National calling plans $45 or higher, and is subject to change without notice. New activation and 2-year service agreement required. Maximum 4 lines per account. Equipment available while supplies last. Mobile-to-mobile minutes apply to calls between Cellular One customers while on the 19-State network (i.e., Cellular One Coverage Area as designated on Calling Plan and Coverage Brochures). Night minutes apply to calls made from 8:00 p.m. to 5:59 a.m. Monday through Friday. -

Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Spring 1987 Connecticut College

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Alumni News Archives Spring 1987 Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Spring 1987 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Spring 1987" (1987). Alumni News. Paper 242. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews/242 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. The Connecticut College . Alumni Magazine And Justice For All? - ConneclcuThe t- t Coll~ AlumnI MC(pzine Volume 64, No.3, Spring 1987 Editorial Board: Vivian Segall '73, Editor (12 DOINGjUSTICLA CAREER IN THE LAW Smith Court, Noank, CT 06340) / Margaret By Patricia McGowan Wald '48 Stewart Van Patten '87, Editorial Assistant / Katherine Gould '81/ wayne Swanson / THE FUTURE OF SOCIAL SECURITY Susan Baldwin Kietzman '82/ Marilyn By Dorcas R. Hardy '68 4 Ellman Frankel '64 / Louise Stevenson Andersen '41, Class Notes Editor / Ellen Hcfheimer Beumann '66 and Kristin TV JUSTICE FOR CHILDREN Stahlschmidt Lambert '69, ex officio / By Peggy Walzer Chorren. '49 7 William Van Saun, Designer. THE SEARCH FOR SHELTER The Connecticut College Alumni Magazine By Nora Richter Greer '75 II (USPS 129-140). Official publication of the Connecticut College Alumni Association. All publication rights reserved. Contents CLASS NOTES 14 reprinted only by permission of the editor. -

The Home of the Brave MCSOL Salutes Our Students and Alumni in the Military

Non-Profit Organization U.S. Postage PAID Jackson, MS Permit #967 A CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY MISSISSIPPI COLLEGE SCHOOL OF LAW MISSISSIPPI COLLEGE SCHOOL OF LAW / SUMMER 2009 151 EAST GRIFFITH STREET amıcus JACKSON, MS 39201 THE HOME OF THE BRAVE MCSOL SALUTES OUR STUDENTS AND ALUMNI IN THE MILITARY Mark Your Calendar FIRST FRIDAY ALUMNI AND IS NOW FIRST REUNION WEEKEND WEDNESDAY April 30 – May 1, 2010 Join us for lunch with Location TBA Dean Jim Rosenblatt 11:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. AREA ALUMNI in the MCSOL GATHERINGS Student Center To find out when Dean Rosenblatt will be in your area, August 5 visit http://law.mc.edu/alumni/ September 2 upcoming_events.htm October 7 TO RSVP OR FOR November 4 MORE INFORMATION December 2 ABOUT THESE EVENTS, CONTACT: FAMILY DAY Whitney Whittington, February 19, 2010 Director of Annual Giving and MCSOL Alumni Relations at 601.925.7175 Campus or [email protected] The Heritage Society The MCSOL Heritage Society honors those who make planned gifts to the law school, including provisions for MCSOL in wills, life insurance policies, and other types of gifts that become effective at the end of a donor’s lifetime. • Mark Sledge ’80, a partner in the Jackson- based firm of Grenfell, Sledge and Stevens, is one of the Heritage Society’s newest members. • On the Cover: Sledge made a gift of $100,000 to MCSOL through life insurance. “By using the money that MCSOL honors the men I was gifting to MCSOL on an annual basis and purchasing a life insurance policy benefitting and women who serve the law school, I was able to substantially increase the overall value of my gift,” Sledge in the courtroom and explains. -

Major Milestones in Academic Excellence

The magazine of the first law school in the Pacific Northwest | Fall 2009 Symeon C. Symeonides Becomes Dean 1984 1999 Carlton J. Snow Helps Establish the Center for 1959 Dispute Resolution WUCL Wins National Moot Court Championship First Willamette Law Journal Created Major Milestones in Academic Excellence On the Cover On the heels of the school’s 125th anniversary celebration, the College of Law marks four more recent milestones in its rich history. Willamette Lawyer | Fall 2009 Major Milestones in Academic Excellence 14 | CDR Silver Anniversary 16 | National Moot Court Championship Richard Birke reflects on recent innovations and what The Class of 1960 looks back on the National Moot lies ahead for the Center for Dispute Resolution Court Championship, when Willamette came seemingly out of nowhere to take highest honors 5 | Robin Morris Collin Honored The director of the Sustainability Law Program is recognized for her civic engagement 10, 26 | Profiles in Leadership The law school community welcomes the newest member of the faculty and recognizes a few of its outstanding alumni and students 8 | 25 Years in China WUCL celebrates the 25-year anniversary of its summer exchange program in Shanghai, China 4 | 123rd Commencement Ceremony A new generation of Willamette lawyers graduates and enters the profession Fall 2009 • Vol. IX, No. 2 Dean In This Issue … Symeon C. Symeonides Departments Editor Anne Marie Becka A Message From the Dean 2 Major Events Graphic Designer Willamette Again Surpasses Peers on Bar Exam 3 Michael A. Wright National Jurist Ranks WUCL a ‘Best Value’ 3 Class Action Editor Commencement 2009 4 Cathy McCann Gaskin JD’02 WUCL Welcomes Class of 2012 5 Morris Collin Receives Civic Engagement Award 5 Contributors International Law Weekend–West 6 Linda Alderin News Briefs 7 Candace Bolen Class Action 29 Mike Bennett BA’70 Alumni Events Richard Birke Greek Cruise 35 Richard Breen Salt Lake City and Seattle Receptions 36 David A. -

Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution

Mitchell Hamline School of Law Mitchell Hamline Open Access DRI Press DRI Projects 12-1-2020 Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution Howard Gadlin Nancy A. Welsh Follow this and additional works at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/dri_press Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Gadlin, Howard and Welsh, Nancy A., "Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution" (2020). DRI Press. 12. https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/dri_press/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the DRI Projects at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in DRI Press by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution Published by DRI Press, an imprint of the Dispute Resolution Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law Dispute Resolution Institute Mitchell Hamline School of Law 875 Summit Ave, St Paul, MN 55015 Tel. (651) 695-7676 © 2020 DRI Press. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020918154 ISBN: 978-1-7349562-0-7 Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota has been educating lawyers for more than 100 years and remains committed to innovation in responding to the changing legal market. Mitchell Hamline offers a rich curriculum in advocacy and problem solving. The law school’s Dispute Resolution Insti- tute, consistently ranked in the top dispute resolution programs by U.S. News & World Report, is committed to advancing the theory and practice of conflict resolution, nationally and inter- nationally, through scholarship and applied practice projects. -

Issue 3 December 2007 the Student Newspaper at Cleveland-Marshall College of Law

Christmas Ale is What hap- New “Iron awesome pened to Chef” hails Three members of The Thanksgiving? from C-town Gavel staff research and The Gavel explores the Chef Michael Symon is explore the beer that has commercialization of the new Iron Chef. He changed the lives of the the holiday season. shares a special recipe C-M community. for law students. LAW, PAGE 4 OPINION, PAGE 8 LAW, PAGE 4 THE GAVEL VOLUME 56, ISSUE 3 DECEMBER 2007 THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER AT CLEVELAND-MARSHALL COLLEGE OF LAW C-M to implement Tuition increased new grading for 2007-08 without system student notice By Michelle Todd By Kevin Shannon that tuition increases ought to be STAFF WRITER STAFF WRITER Pending approval from On June 28, 2007, the Cleve- expected by students, explain- Cleveland State University’s land State Board of Trustees ing, “that’s the way things go.” Faculty Senate, the grading sys- voted to increase the law school’s Another 3-L, Christian tem at Cleveland-Marshall will tuition by 10 percent. This year’s Moore, stated that he would soon convert to a more widely tuition of $16,477.50 for full have appreciated some form of recognized format that will af- time in-state students is a $1,495 notice about the increase. He ford professors a broader range increase from last year’s tuition. explained that the information of grades with which to reward While the law school’s tuition would have been helpful in help- their students. increased by 10 percent, graduate ing him plan his budget for the school year. -

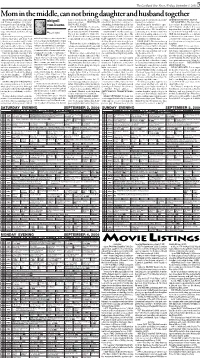

Mom in the Middle, Can Not Bring Daughter and Husband Together DEAR ABBY: I Was Recently Mar- Want to Tell Them Who Did It

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, September 1, 2006 5 Mom in the middle, can not bring daughter and husband together DEAR ABBY: I was recently mar- want to tell them who did it. I really coming a young woman, and sharing transsexual. Your friend needs under- BRENDA IN AUSTIN, TEXAS ried. I have a daughter, “Courtney,” abigail need some advice. — HURTING IN a bed with her father could be too standing, not isolation. DEAR BRENDA: The type of par- from a previous relationship. Things van buren HAYWARD, CALIF. stimulating, for both of them. If he has By all means he should see a psy- ties you have described are more for were great before the wedding. We DEAR HURTING: Pick up the further doubts about this, he should chiatrist — one who specializes in adults than for children. It is more even included Courtney in the plan- phone and call the Rape, Abuse and consult his daughter’s pediatrician. gender disorders. He should have important that your little girl be able ning. Afterward, however, things Incest National Network (RAINN). DEAR ABBY: About a month ago, counseling if he wants to take this to enjoy her birthday with some of dear abby turned sour. • The toll-free number is (800) 656- I was shocked out of my shoes. My where it is heading, and also to cope HER friends than it be a command Courtney kept causing problems 4673. Counselors there will guide you longtime friend, “Orville,” told me he with the loss of his friends. It would performance for your sisters. -

2006 Marketing Advertising

A SUPPLEMENT TO 2006 FACT PACK 4th ANNUAL GUIDE TO ADVERTISING MARKETING Published February 27, 2006 © Copyright 2006 Crain Communications Inc. 2 | Advertising Age | FactPack FactPack | Advertising Age | 3 FACT PACK 2006 CONTENTS TOP LINE DATA ON THE ADVERTISING AND MEDIA INDUSTRIES In a pdf version, click anywhere on the items below to jump directly to the page. GENERAL MOTORS CORP. is the top marketer by ad spending in the U.S. but who ranks Advertising & Marketing first on a global basis? A spot for Fox TV’s American Idol on Wednesdays at prime- Top five U.S. advertisers and their agencies . .6-7 time commands the most dollars per :30 ($518,466), but how much more is that than Top U.S. advertisers . .8 a spot for runner-up CSI:Crime Scene Investigation on CBS-TV the following night? And what about that growth in a Super Bowl :30 spot since the $42,000 average cost Top U.S. megabrands . .9 paid per :30 at Super Bowl I in 1967? Omnicom Group may be the world’s biggest U.S. ad spending totals by media . .10 marketing organization but how do its agency networks stack up against their com- Top U.S. advertisers by media . .11-13 petition? How big and far-reaching are those multifaceted media goliaths? It’s all in Top global marketers and spending in top 10 countries . .14-15 the FactPack, whether in print form on your desk, or a click away on your computer or network. Consumer brand market share leaders in select categories . -

A Complete Television Shows List Europe & Asia North America

A Complete Television Shows List Europe & Asia Alpha 0.7 - Der Feind in dir Liebe und Wahn Dangerous Liaisons Lüthi und Blanc Der Bestatter Polizeiruf 110 Die Snobs Stunthero Dr. Klein Stuttgart Homicide Eine für alle - Frauen können's besser Supermodel Geld oder Leben Tanzalarm! Lasko - The Fist of God Tatort North America 24 Banshee Burn Notice 90210 Barnaby Jones Californication $#*! My Dad Says Baywatch Carpoolers 10 Things I Hate About You Baywatch Nights Castle 12 Miles of Bad Road Beauty and the Beast Chaos 24: Redemption Beverly Hills, 90210 Charlie's Angels A to Z Big Time Rush Charmed Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Black Scorpion Chicago Hope Airwolf Body of Proof Chiefs Alias Bones Chop Shop Amen Boomtown Chuck American Horror Story Bosch Cleopatra 2525 Angel Brooklyn Bridge Cold Case Awake Brother's Keeper CollegeHumor Originals B.J. and the Bear Brothers & Sisters Cover Up Bad Judge Buffy the Vampire Slayer Crime Story Bad Teacher Bunheads Criminal Minds Crossing Jordan Hardball Last Resort Crumbs Hardcastle and McCormick Lauren CSI: Crime Scene Investigation Harry O LAX CSI: Miami Hart of Dixie Legends CSI: NY Hart to Hart Leo & Liz in Beverly Hills Curb Your Enthusiasm Hawaii Level 9 Dark Skies Hawaii Five-0 Leverage Day Break Hawaiian Heat Life Days of Our Lives Heroes Limestreet Designing Women Highway to Heaven Logan's Run Desperate Housewives Hit the Floor Longmire Dexter Hollywood Beat Lost Downtown House MacGruder and Loud Dynasty Houston Knights Magic City E-Ring How to Get Away with Murder Major Crimes Eagleheart Hunter -

Conceptual Change in the Emergence of Tort Law

Becoming Responsible: Conceptual Change in the Emergence of Tort Law A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Caleb Goltz IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Joan Tronto, Adviser December 2015 © Caleb Goltz 2015 Acknowledgements During the course of this project, many people have helped in many ways. The initial framing of the project began under the direction of Nancy Luxon, and her early input shaped the structure of this project. Joan Tronto served as a patient adviser, providing graceful guidance all along the way. Elizabeth Beaumont stuck with this project from conception to completion, and provided an invaluable legal perspective on the project. JB Shank generously kept an eye on my historical accounts, and shared his love for the Fenlands. Graduate colleagues at the University of Minnesota also shaped this project and provided support along the way. Members of the Whirling Dervishes Dissertation Writing Group – Josh Anderson, Jen Gagnon, Andrew Wiley, Sema Binay, and Dara McCracken – read and commented on early drafts of several chapters. Adam Dahl, Garnet Kindervater, and Chase Hobbs-Morgan listened to me pitching early versions of these ideas with patience and enthusiasm. The fieldwork for this project was funded by a 2011 Hella Mears Graduate Fellowship from the Center for German and European Studies at the University of Minnesota. Writing during the 2012-2013 academic year was funded by a Marbury- Efimenco Fellowship from the Department of Political Science at the University of Minnesota. I am very grateful for those research funds. My colleagues in the Political Science Department at Hartwick College have been tremendous as I have slowly finished the writing process. -

The English Law School London: Sweet & Maxwell

Amicus Curiae The Journal of the Society for Advanced Legal Studies Inside ... Special issue: ‘Reflecting on Blackstone’s Tower’ Introduction Read more on pag e 311 Articles Read more on pag e 314 Notes Read more on pag e 501 News and Events Read more on pag e 523 Contributors’ Profiles Read more on pag e 526 Visual Law Read more on pag e 531 Series 2, Vol 2, No 3 310 Amicus Curiae CONTENTS Special Issue: ‘Reflecting on Blackstone’s Tower’ Guest Editors: Fiona Cownie & Emma Jones Editor’s Introduction Notes Michael -Palmer . 311 The Independent Panel’s Report on Special Issue Articles Judicial Review (CP 407) and the Government’s Consultation Document Blackstone’s Tower in Context on Judicial Review Reform (CP 408) Fiona-Cownie & Emma-Jones Patrick -J- Birkinshaw . 501 . 314 University of London Refugee Law Twining’s Tower and the Challenges of Clinic Online Launch Making Law a Humanistic Discipline Carl -Stychin . 521 David-Sugarman .. 334 The Tower News and Events Completion of IALS Anthony-Bradney . 352 Transformation Project . 523 Rutland Revisited: Reflections on Georg Schwarzenberger Prize . the Relationships between the Legal 524 Academy and the Legal Profession IALS Library . 524 Steven-Vaughan . 371 Selected Upcoming Events . 524 Experiencing English Law Schools: Contributors’ Profiles . 526 The Student Perspective Visual Law Jessica-Guth, Fiona-Cownie China’s Three Internet Courts & Emma-Jones . .. 390 Yang-Lin . 531 Building Access Routes into Blackstone’s Tower: Including Disability Perspectives in the Liberal Law School Amicus Curiae Contacts Abigail-Pearson .. 406 Editor: Professor Michael Palmer, SOAS and IALS, University of Should We Rethink the Purposes of London the Law School? A Case for Decolonial Thought in Legal Pedagogy Production Editor: Marie Selwood Foluke-Adebisi .