The Gospel According to a Personal View Owen O'sullivan OFM Cap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marian Library Newsletter: Vol. 12, Nos

tl';iO i? -~J 3 ' f MARIAN LIBRARY Ar~-"'" l :NIVERSITY OF DAYTON ·'f DAYTON 9, OHIO ' . Volume XII - Number 6 and 7 March-April, 1957 Fifth Marian Institute of the Me rian Library OUR LADY AND CONVEHTS Friday and Saturday, June 14-15, 1957 Speakers: DALE FRANCIS, a convert to Catholicism, anc a well-known jour nalist who has had a varied career as a student, minister, editor, public relations director, and a >ostle. He recently returned t+ the United States after a y£ u of apostolic work in Cuba. I I FR. TITUS CRANNY, S. A., national director c F the Chair of Unity I Octave, and editor of The Lamp, the pub:ication of the Society of the Atonement, founded by Father P< ul and his disciples, all converts from Episcopalianism. Mr. Francis and Fr. Titus will each speak on both days of the Institute. Discussion periods will allow amplf time for questions. Names of other speakers on the program v.. II be announced in the May issue of the NEWSLETTER. The MARIAN LIBRARY NEWSLETTER is publish• t monthly except July, August, and September, by the Marian Library, Univ< ·sity of Dayton, Dayton 9, Ohio. The NEWSLETTER will be .~ent free of charg. to anyone requesting it. MARIAN II\ STITUTE OF CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY The first two courst s in the Marian Institute recently organized by the Catholic University oi America will be offered this summer by Fr. Eamon R. Carroll, 0. Carm., dir •ctor of the Institute, and president of the Mariological Society of America. 1e courses are: GENERAL MARl 'LOGY I (Principles and methodology; Christological foundatiom Mary's functions: Divine Maternity, Spiritual Mater- nity, Mediation of Graces, Universal Queenship) MARIAN DOCTRINES OF MODERN POPES (Analysis of major papal statements '")f the last century) The Marian Institute 1as been established to provide a systematic training in theology about the Blessed Virgin. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project PETER KOVACH Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: April 18, 2012 Copyright 2015 ADST Q: Today is the 18th of April, 2012. Do you know ‘Twas the 18th of April in ‘75’? KOVACH: Hardly a man is now alive that remembers that famous day and year. I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts. Q: We are talking about the ride of Paul Revere. KOVACH: I am a son of Massachusetts but the first born child of either side of my family born in the United States; and a son of Massachusetts. Q: Today again is 18 April, 2012. This is an interview with Peter Kovach. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. You go by Peter? KOVACH: Peter is fine. Q: Let s start at the beginning. When and where were you born? KOVACH: I was born in Worcester, Massachusetts three days after World War II ended, August the 18th, 1945. Q: Let s talk about on your father s side first. What do you know about the Kovaches? KOVACH: The Kovaches are a typically mixed Hapsburg family; some from Slovakia, some from Hungary, some from Austria, some from Northern Germany and probably some from what is now western Romania. Predominantly Jewish in background though not practice with some Catholic intermarriage and Muslim conversion. Q: Let s take grandfather on the Kovach side. Where did he come from? KOVACH: He was born I think in 1873 or so. -

Vampire Storytellers Handbook (3Rd Edition)

Vampire Storytellers Handbook 1 Vampire Storytellers Handbook By Bruce Baugh, Anne Sullivan Braidwood, Deird’re Brooks, Geoffrey Grabowski, Clayton Oliver and Sven Skoog Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Most Important Part... ............................................................................................................................................................6 ...And the Most Important Rule .....................................................................................................................................................6 How to Use This Book...................................................................................................................................................................7 The Game as it is Played..............................................................................................................................................................7 Cool, Not Kewl ..............................................................................................................................................................................9 Violence is Prevalent but Desperate...........................................................................................................................................10 Vampire Music ............................................................................................................................................................................10 -

Al-QAEDA and the ARYAN NATIONS

Al-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCAULDIAN PERSPECTIVE by HUNTER ROSS DELL Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON DECEMBER 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For my parents, Charles and Virginia Dell, without whose patience and loving support, I would not be who or where I am today. November 10, 2006 ii ABSTRACT AL-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCALTIAN PERSPECTIVE Publication No. ______ Hunter Ross Dell, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2006 Supervising Professor: Alejandro del Carmen Using Foucauldian qualitative research methods, this study will compare al- Qaeda and the Aryan Nations for similarities while attempting to uncover new insights from preexisting information. Little or no research had been conducted comparing these two organizations. The underlying theory is that these two organizations share similar rhetoric, enemies and goals and that these similarities will have implications in the fields of politics, law enforcement, education, research and United States national security. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... -

Bonfield and Engel

THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES IMES CAPSTONE PAPER SERIES DIVIDED AND CONQUERED? SHIFTING DYNAMICS AND MECHANISMS OF CONTROL IN TURKISH CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS CRAIG E. BONFIELD BRIAN E. ENGEL MAY 2012 THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES THE ELLIOTT SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY © 2012 DIVIDED AND CONQUERED? SHIFTING DYNAMICS AND MECHANISMS OF CONTROL IN TURKISH CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS (Click heading to jump to section) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 METHODOLOGY 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 6 A CIVIL-MILITARY THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 7 Professionalism as an Analytical Conception 8 Differentiating Civilian Control: Objective & Subjective 11 UNPROFESSIONALISM AND SUBJECTIVE CONTROL: THE TURKISH CASE 14 Roots of Subjective Control 1900-1940 15 Challenges to the Order 1940-1960 17 Seeking the Balance 1960-1971 21 Maximizing Control 1970-1980 23 The Zenith of Power 1980-1990 25 Sowing the Seeds of Irony 1990-1999 26 DIVIDING AND CONQUERING THE PASHAS 30 Turkey’s Subjective Evolution 31 Setting the Stage for Conquest 36 Subjective Shifts on the Heels of Copenhagen 40 A House Divided Revealed 43 An E-Compromise 50 The Civil-Military Problematique Reborn 56 DIVERGING PATHS IN ANKARA 58 Democratic Backlash 59 The Enemy of my Enemy & The Threat Within 62 The Dangers of Division 64 Positive Alternatives 66 The Future Path 70 APPENDIX OF FIGURES 72 Figure A – Progression of Relative Political Strength 72 Figure B – Continuum of Turkish Subjective Control 73 INTERVIEWS CONDUCTED 74 WORKS CITED 76 Bonfield & Engel 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was made possible with the help and support of numerous individuals. First and foremost, we are grateful to Dr. -

November 5, 2019

YOU'RE INVITED TO Medjugorje “My first visit to Medjugorje was one of the highlights of my life! It really got my attention and heightened my devotion to Our Lady. I am looking forward to going on this pilgrimage if I can make it.” Tom Monaghan Founder & CEO \[ OCTOBER 30 - NOVEMBER 5, 2019 This Legatus pilgrimage is meant to be an experience of something new and intangible – a leap of faith that will challenge your heart to consider the Blessed Mother & Her Son, through the eyes of a culture that has experienced something miraculous. This journey will require practical preparation, such the ability to hike on uneven and rocky terrain with steep inclines and heights. It will also require flexibility with schedules and comfort. This pilgrimage will be a rugged journey that will allow Legatus members to travel together to explore a simple village filled with the most radical faith. Join us! \[ Wednesday, October 30: Depart USA Depart on independently arranged overnight flights to Split, Croatia (SPU). Thursday, October 31: Croatia | Medjugorje Upon arrival in Croatia, depart via a small group transfer to the village of Medjugorje.** Upon arrival, check into your hotel and freshen up before an orientation tour of the Medjugorje experience. Learn about the apparitions that have been occuring for the last 37 years and the history of this miraculous place of prayer. Celebrate an opening Mass followed by a Welcome Dinner at the hotel. Overnight in Medjugorje. Friday, November 1 – Monday, November 4: Medjugorje Throughout the week, embrace the pilgrim experience by opening your heart to the culture, people, and history of the storied village of Medjugorje and learn why millions of pilgrims come to this beautiful countryside every year. -

Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Modern European Roman Catholicism

APPARITIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY IN MODERN EUROPEAN ROMAN CATHOLICISM (FROM 1830) Volume 2: Notes and bibliographical material by Christopher John Maunder Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds Department of Theology and Religious Studies AUGUST 1991 CONTENTS - VOLUME 2: Notes 375 NB: lengthy notes which give important background data for the thesis may be located as follows: (a) historical background: notes to chapter 1; (b) early histories of the most famous and well-documented shrines (La Salette, Lourdes, Pontmain, Beauraing, Banneux): notes (3/52-55); (c) details of criteria of authenticity used by the commissions of enquiry in successful cases: notes (3/71-82). Bibliography 549 Various articles in newspapers and periodicals 579 Periodicals specifically on the topic 581 Video- and audio-tapes 582 Miscellaneous pieces of source material 583 Interviews 586 Appendices: brief historical and bibliographical details of apparition events 587 -375- Notes NB - Format of bibliographical references. The reference form "Smith [1991; 100]" means page 100 of the book by Smith dated 1991 in the bibliography. However, "Smith [100]" means page 100 of Smith, op.cit., while "[100]" means ibid., page 100. The Roman numerals I, II, etc. refer to volume numbers. Books by three or more co-authors are referred to as "Smith et al" (a full list of authors can be found in the bibliography). (1/1). The first marian apparition is claimed by Zaragoza: AD 40 to St James. A more definite claim is that of Le Puy (AD 420). O'Carroll [1986; 1] notes that Gregory of Nyssa reported a marian apparition to St Gregory the Wonderworker ('Thaumaturgus') in the 3rd century, and Ashton [1988; 188] records the 4th-century marian apparition that is supposed to have led to the building of Santa Maria Maggiore basilica, Rome. -

Memoirs of the Author Concerning the HISTORY of the BLUE ARMY Dm/L Côlâhop

Memoirs of the author concerning The HISTORY of the BLUE ARMY Dm/l côlâhop Memoirs of the author concerning The HISTORY of the BLUE AR M Y by John M. Haffert - ' M l AMI International Press Washington, N.J. (USA) 07882 NIHIL OBSTAT: Rev. Msgr. William E. Maguire, S.T.D. Having been advised by competent authority that this book contains no teaching contrary to the Faith and Morals as taught by the Church, I approve its publication accord ing to the Decree of the Sacred Congregation for the Doc trine of the Faith. This approval does not necessarily indi cate any promotion or advocacy of the theological or devo tional content of the work. IMPRIMATUR: Most Rev. John C. Reiss, J.C.D. Bishop of Trenton October 7, 1981 © Copyright, 1982, John M. Haffert ISBN 0-911988-42-4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro duced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. This Book Dedicated To The Most Rev. George W. Ahr, S.T.D., Seventh Bishop of Trenton — and to The Most Rev. John P. Venancio, D.D., Second Bishop of Leiria - Fatima and Former International President, The Blue Army of Our Lady of the Rosary of Fatima Above: The Most Rev. John P. Venancio, D.D. (left), and the Most Rev. George W. Ahr, S.T.D. (right), at the dedication and blessing of the Holy House, U.S.A. -

Guide for the War Below/Underground Soldier

Underground Soldier, by Marsha Skrypuch Teacher’s Guide Summary In 1943, in the midst of World War II, Luka is an injured slave labourer in a Nazi work camp. He escapes in a wagon of corpses and tries to walk back home to Kyiv in the hopes of finding his father who had been imprisoned in Siberia by the Soviets (Luka's mother was captured by the Nazis and is a slave labourer at an unknown camp). Instead of walking away from the war, he ends up walking right into the Front. He is saved by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, a multi-ethnic group of underground freedom fighters who steal weapons from the Nazis and the Soviets and fight both of these brutal regimes. Luka joins and fights with them, but he never loses his desire to find his parents and somehow be reunited with his beloved Lida, who he last saw at the slave labour camp. Underground Soldier is a companion novel to Stolen Child and Making Bombs for Hitler. Historical Background World War II is popularly viewed as the war against Hitler and the Nazis, and while this is largely true from a western perspective, to Ukrainians, Poles, and other Slavs whose homelands were the battleground, the Nazis were not the only enemy. Stalin and the Soviets also committed genocide before and during World War II, and they were responsible for even more deaths than the Nazis. Why are Hitler's crimes common knowledge and Stalin's are not? In part, because Stalin was allied with us during the latter part of WWII. -

Guristas Epic Arc Guide by Jowen Datloran

Guristas Epic Arc Guide by Jowen Datloran Smash and Grab Introduction This is an epic mission arc mission guide that will take you through the various encounters and tasks in the Guristas epic arc level 3 mission chain called “Smash and Grab”. While the guide contains detailed info on encounter opponents and provides hints on trigger spawn mechanics, this was not been my primary goal. Instead I focused on noting down all mission briefings and communications to provide clear insight in the ongoing story. I have included mission debriefings too, when they have contained a little more information than simply a pad on the back for a job well done. Also, in the end of the guide is an “Info on” section where all background info to the various missions is included. This particular epic arc has three starting locations, giving a large span of possible standing requirements to start the arc. The first agent is Arment Caute who is located at the Gallente Counter-intelligence Center in the Orvolle solar system. Before Arment is willing to hand over her first mission of the arc (Enemy of my Enemy) you need to have a minimum of 4.35 in effective standing (skills included) with either the Federal Intelligence Office corporation or the Gallente Federation faction. The second agent is Atma Aulato who is located at the Counter Intelligence Center in the Obe solar system. Before Atma is willing to hand over her first mission of the arc (Turning Coat) you need to have a minimum of 4.35 in effective standing (skills included) with either the Ytiri corporation or the Caldari State faction. -

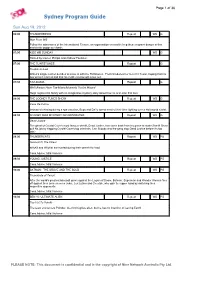

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 36 Sydney Program Guide Sun Aug 19, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Man From Mi5 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G Trouble-In-Law Wilma's single mother decides to move in with the Flintstones. Fred introduces her to a rich Texan, hoping that the two will get married and that his mother-in-law will move out. 07:30 TAZ-MANIA Repeat G We'll Always Have Taz-Mania/Moments You've Missed Hugh regales the family with an imaginative mystery story about how he and Jean first met. 08:00 THE LOONEY TUNES SHOW Repeat WS G Casa De Calma Instead of relaxing during a spa vacation, Bugs and Daffy spend most of their time fighting over a Hollywood starlet. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Dead Justice The ghost of Crystal Cove's most famous sheriff, Dead Justice, has come back from his grave to make Sheriff Stone quit his job by trapping Crystal Cove's top criminals. Can Scooby and the gang stop Dead Justice before it's too late? 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG Survival Of The Fittest WilyKit and WilyKat are hunted during their search for food. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG Triumvirate of Terror! After the world's greatest baseball game against the Legion of Doom, Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman face off against their arch-enemies Joker, Lex Luthor and Cheetah, who gain the upper hand by switching their respective opponents. -

Kodak Catholicism: Miraculous Photography and Its Significance at a Post- Conciliar Marian Apparition Site in Canada

CCHA, Historical Studies, 70 (2004), 71-93 Kodak Catholicism: Miraculous Photography and its Significance at a Post- Conciliar Marian Apparition Site in Canada Jessy C. PAGLIAROLI There are many people who feel that the ability to maintain an enchanted religious worldview has become increasingly difficult for American and Canadian Catholics in the years following the Second Vatican Council. Proponents of this view have often pointed to three different factors to support their claim. These include the notion that heightened diabolical activity from Satan and his minions is luring people away from knowing and perceiving the action of God’s grace in their life; that living in a predominantly secular and materialistic culture has devalued the mystical and the merits of religion; and lastly, that the modernization of the Catholic Church, mainly as a result of the reforms of the Second Vatican council, has made it increasingly difficult for people to perceive the propinquity of the sacred within the Church. Those who note the last factor, often suggest that architectural changes, the use of the vernacular language, and the gradual suppression of paraliturgical activities and personal sacramental objects such as rosaries, scapulars, religious medals, and so forth, has functioned to de- emphasize the immediacy of the supernatural within Catholicism.1 While Catholicism may seem less mysterious and enchanted to certain church going Catholics, especially those born before Vatican II, there exists, beyond the walls of the parish church and outside of standard liturgical celebrations, a Catholic culture made up of different movements that is driven by a desire to re-awaken what it perceives is a 1 The following represents a summary of responses given by various Canadian and American Catholics interviewed by the author.