Serializing the Middle Ages: Television and the (Re)Production of Pop Culture Medievalisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marian Library Newsletter: Vol. 12, Nos

tl';iO i? -~J 3 ' f MARIAN LIBRARY Ar~-"'" l :NIVERSITY OF DAYTON ·'f DAYTON 9, OHIO ' . Volume XII - Number 6 and 7 March-April, 1957 Fifth Marian Institute of the Me rian Library OUR LADY AND CONVEHTS Friday and Saturday, June 14-15, 1957 Speakers: DALE FRANCIS, a convert to Catholicism, anc a well-known jour nalist who has had a varied career as a student, minister, editor, public relations director, and a >ostle. He recently returned t+ the United States after a y£ u of apostolic work in Cuba. I I FR. TITUS CRANNY, S. A., national director c F the Chair of Unity I Octave, and editor of The Lamp, the pub:ication of the Society of the Atonement, founded by Father P< ul and his disciples, all converts from Episcopalianism. Mr. Francis and Fr. Titus will each speak on both days of the Institute. Discussion periods will allow amplf time for questions. Names of other speakers on the program v.. II be announced in the May issue of the NEWSLETTER. The MARIAN LIBRARY NEWSLETTER is publish• t monthly except July, August, and September, by the Marian Library, Univ< ·sity of Dayton, Dayton 9, Ohio. The NEWSLETTER will be .~ent free of charg. to anyone requesting it. MARIAN II\ STITUTE OF CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY The first two courst s in the Marian Institute recently organized by the Catholic University oi America will be offered this summer by Fr. Eamon R. Carroll, 0. Carm., dir •ctor of the Institute, and president of the Mariological Society of America. 1e courses are: GENERAL MARl 'LOGY I (Principles and methodology; Christological foundatiom Mary's functions: Divine Maternity, Spiritual Mater- nity, Mediation of Graces, Universal Queenship) MARIAN DOCTRINES OF MODERN POPES (Analysis of major papal statements '")f the last century) The Marian Institute 1as been established to provide a systematic training in theology about the Blessed Virgin. -

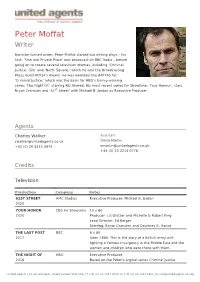

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

November 5, 2019

YOU'RE INVITED TO Medjugorje “My first visit to Medjugorje was one of the highlights of my life! It really got my attention and heightened my devotion to Our Lady. I am looking forward to going on this pilgrimage if I can make it.” Tom Monaghan Founder & CEO \[ OCTOBER 30 - NOVEMBER 5, 2019 This Legatus pilgrimage is meant to be an experience of something new and intangible – a leap of faith that will challenge your heart to consider the Blessed Mother & Her Son, through the eyes of a culture that has experienced something miraculous. This journey will require practical preparation, such the ability to hike on uneven and rocky terrain with steep inclines and heights. It will also require flexibility with schedules and comfort. This pilgrimage will be a rugged journey that will allow Legatus members to travel together to explore a simple village filled with the most radical faith. Join us! \[ Wednesday, October 30: Depart USA Depart on independently arranged overnight flights to Split, Croatia (SPU). Thursday, October 31: Croatia | Medjugorje Upon arrival in Croatia, depart via a small group transfer to the village of Medjugorje.** Upon arrival, check into your hotel and freshen up before an orientation tour of the Medjugorje experience. Learn about the apparitions that have been occuring for the last 37 years and the history of this miraculous place of prayer. Celebrate an opening Mass followed by a Welcome Dinner at the hotel. Overnight in Medjugorje. Friday, November 1 – Monday, November 4: Medjugorje Throughout the week, embrace the pilgrim experience by opening your heart to the culture, people, and history of the storied village of Medjugorje and learn why millions of pilgrims come to this beautiful countryside every year. -

Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Modern European Roman Catholicism

APPARITIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY IN MODERN EUROPEAN ROMAN CATHOLICISM (FROM 1830) Volume 2: Notes and bibliographical material by Christopher John Maunder Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds Department of Theology and Religious Studies AUGUST 1991 CONTENTS - VOLUME 2: Notes 375 NB: lengthy notes which give important background data for the thesis may be located as follows: (a) historical background: notes to chapter 1; (b) early histories of the most famous and well-documented shrines (La Salette, Lourdes, Pontmain, Beauraing, Banneux): notes (3/52-55); (c) details of criteria of authenticity used by the commissions of enquiry in successful cases: notes (3/71-82). Bibliography 549 Various articles in newspapers and periodicals 579 Periodicals specifically on the topic 581 Video- and audio-tapes 582 Miscellaneous pieces of source material 583 Interviews 586 Appendices: brief historical and bibliographical details of apparition events 587 -375- Notes NB - Format of bibliographical references. The reference form "Smith [1991; 100]" means page 100 of the book by Smith dated 1991 in the bibliography. However, "Smith [100]" means page 100 of Smith, op.cit., while "[100]" means ibid., page 100. The Roman numerals I, II, etc. refer to volume numbers. Books by three or more co-authors are referred to as "Smith et al" (a full list of authors can be found in the bibliography). (1/1). The first marian apparition is claimed by Zaragoza: AD 40 to St James. A more definite claim is that of Le Puy (AD 420). O'Carroll [1986; 1] notes that Gregory of Nyssa reported a marian apparition to St Gregory the Wonderworker ('Thaumaturgus') in the 3rd century, and Ashton [1988; 188] records the 4th-century marian apparition that is supposed to have led to the building of Santa Maria Maggiore basilica, Rome. -

The Gospel According to a Personal View Owen O'sullivan OFM Cap

The Gospel according to MARK: a personal view Owen O’Sullivan OFM Cap. 1 © Owen O’Sullivan OFM Cap., 2007. 2 The Gospel according to MARK: a personal view Contents Page Preface iv Sources used v Introduction 1 Main Text 6 3 Preface I was stationed in the Catholic parish of Christ the Redeemer, in Lagmore, West Belfast, Northern Ireland, between 2001 and 2007. When the liturgical year 2005-06 began on the first Sunday of Advent, 27 November 2005, with the Gospel of Mark as the Sunday Gospel, I decided to begin a study of it, in order to learn more about it and understand it better, and, hopefully, to be able to preach better on it at Sunday Mass. I also hoped that this study would be of benefit to me in my faith. It was never on my mind, then or now, that it be published. It is not good enough for that. I have had no formal training in scripture studies, other than what I learned in preparing for the priesthood. Mostly, it has been a matter of what I learned in later years from reflection in daily prayer and personal study, of which I did a good deal. It took me more than a year to complete the study of Mark, but I found that it carried me along, and I wanted to bring it to completion. I was glad to be able to do that early in 2007. The finished product I printed and bound principally for my own use, simply to make it 4 easier to refer to for study or preaching. -

Memoirs of the Author Concerning the HISTORY of the BLUE ARMY Dm/L Côlâhop

Memoirs of the author concerning The HISTORY of the BLUE ARMY Dm/l côlâhop Memoirs of the author concerning The HISTORY of the BLUE AR M Y by John M. Haffert - ' M l AMI International Press Washington, N.J. (USA) 07882 NIHIL OBSTAT: Rev. Msgr. William E. Maguire, S.T.D. Having been advised by competent authority that this book contains no teaching contrary to the Faith and Morals as taught by the Church, I approve its publication accord ing to the Decree of the Sacred Congregation for the Doc trine of the Faith. This approval does not necessarily indi cate any promotion or advocacy of the theological or devo tional content of the work. IMPRIMATUR: Most Rev. John C. Reiss, J.C.D. Bishop of Trenton October 7, 1981 © Copyright, 1982, John M. Haffert ISBN 0-911988-42-4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro duced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. This Book Dedicated To The Most Rev. George W. Ahr, S.T.D., Seventh Bishop of Trenton — and to The Most Rev. John P. Venancio, D.D., Second Bishop of Leiria - Fatima and Former International President, The Blue Army of Our Lady of the Rosary of Fatima Above: The Most Rev. John P. Venancio, D.D. (left), and the Most Rev. George W. Ahr, S.T.D. (right), at the dedication and blessing of the Holy House, U.S.A. -

Kodak Catholicism: Miraculous Photography and Its Significance at a Post- Conciliar Marian Apparition Site in Canada

CCHA, Historical Studies, 70 (2004), 71-93 Kodak Catholicism: Miraculous Photography and its Significance at a Post- Conciliar Marian Apparition Site in Canada Jessy C. PAGLIAROLI There are many people who feel that the ability to maintain an enchanted religious worldview has become increasingly difficult for American and Canadian Catholics in the years following the Second Vatican Council. Proponents of this view have often pointed to three different factors to support their claim. These include the notion that heightened diabolical activity from Satan and his minions is luring people away from knowing and perceiving the action of God’s grace in their life; that living in a predominantly secular and materialistic culture has devalued the mystical and the merits of religion; and lastly, that the modernization of the Catholic Church, mainly as a result of the reforms of the Second Vatican council, has made it increasingly difficult for people to perceive the propinquity of the sacred within the Church. Those who note the last factor, often suggest that architectural changes, the use of the vernacular language, and the gradual suppression of paraliturgical activities and personal sacramental objects such as rosaries, scapulars, religious medals, and so forth, has functioned to de- emphasize the immediacy of the supernatural within Catholicism.1 While Catholicism may seem less mysterious and enchanted to certain church going Catholics, especially those born before Vatican II, there exists, beyond the walls of the parish church and outside of standard liturgical celebrations, a Catholic culture made up of different movements that is driven by a desire to re-awaken what it perceives is a 1 The following represents a summary of responses given by various Canadian and American Catholics interviewed by the author. -

St Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church Founded 1981 Archbishop Daniel E

September 8, 2019 Twenty-third Sunday in Ordinary Time ST ELIZABETH ANN SETON CATHOLIC CHURCH FOUNDED 1981 ARCHBISHOP DANIEL E. SHEEHAN 5419 N. 114th St. • Omaha, NE 68164 PASTOR Rev. Ryan Lewis (402) 493-2186 ext. 13 [email protected] Parish Office 5419 N 114 St. (114 & Fort) Omaha, Nebraska 68164 Phone: (402) 493-2186 Fax: (402) 493-0630 Email [email protected] Web Site www.stelizabethann.org Summer Office Hours Monday through Friday 9:00 am to Noon; 1:00 pm to 4:00 pm. Office closed noon to 1pm St. James/Seton School William Kelly, Principal 4720 N. 90 St., 68134 Phone: (402) 572-0339 Website: www.sjsomaha.org Email: [email protected] Religious Formation Director: Jo Kusek (P.R.E., Adult Ed. & School Faith Formation) 4720 N. 90 St., 68134 Phone: (402) 572-0369 Email: [email protected] MASS SCHEDULE HOLY DAY SCHEDULE Monday-Friday 5:30 p.m. (except for Christmas, Easter & New Years) Saturday Morning 8:30 a.m. Vigil (Evening Before) 5:30 p.m. Saturday Evening 5:30 p.m. Holy Day **12:10 p.m., 5:30 p.m.** Sunday Morning 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m., Sunday Evening 5:30 p.m. **NOTE MASS TIME CHANGE St. Elizabeth Ann Seton 2 Twenty-third Sunday in Ordinary Time Devotions PARISH STAFF: Our Mother of Perpetual Help Novena Prayers St. James/Seton School: following Saturday 8:30 a.m. Mass William Kelly, Principal Exposition of Blessed Sacrament 4720 N. 90 St.. • Omaha, NE 68134 Phone (402) 572-0339 Thursday 6:00 p.m.-9:00 p.m. -

Ahpeako $1-50

-^..!- .',. .V'.'. '.')aJf N^I^K,Asvr.>?tii£ f Jf E^'^lg^jjK j^gS»¥«W'Wne«aTW-BWl* •mnK^npn«niK?a«)% •»** "^^"^^RT^T * asA Jprw ap f *«>^ii«/«4 A V;-" *s 1 .in i Ti, RGCM To Mfeot na Statue ••iff WRS Fjrsf On f^£M J© Evwy Other Year •' Marian Year Pmm^' WMfclact*! —(NC)-The Na Reported In Sicilian Aid Pusan Fire Victim tional Council of Catholic Men Hen Is »M teat of the prayer composed t^ftfeit^^l-Wr announced that It will hold its By MONSIOMOaV We, SULLIVAN. MCitatlasi eurtstg the. Marian Year. He Ma^se- a aarttfJ . Seoul, Korea -^(NC) — n*ftKSSfy jfWffMMft open convention* every other Rome - (NC) -The Vatican's traditional attitude of haiaigesies of Ave years every time U^peay^ give food and clothing to tjh# PUMI£ Hire victims was War year, instead of annually as in reserve in regard to alleged miraculous happenings has not vouUy with a contrite heart Readers snsy |elt§|tafc*»iaj»r Rehef Services of the National Catholic Welfari^ifterjpnc^ the pait. At the game time, it and keep it la their prayerbooks. ^dgh McLoone. War r^i ^^^4^^ •aid that NCCM Executive Com been in any way altered by reports concerning the "Weeping Service representative in Korea, mittee voted at Its November Madonna" of Syracuse la Sicily. Enraptured by the splendor of yoalr neavenJjr bm*- offered supplies to a hastily- chaplains were-on hand at the THIS HAPPENED in the case meeting to accept the Invitation According to the reports, a ter ty, and impelled by the anxieties or the world, we east formed disaster committee at Its time and removed the Blessed of the alleged visions at Herolds- of Archbishop Richard J. -

-

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

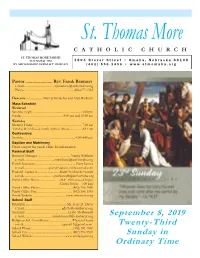

September 8, 2019 Twenty-Third Sunday in Ordinary Time

CATHOLIC CHURCH ST. THOMAS MORE PARISH FOUNDED 1958 4804 Grover Street • Omaha, Nebraska 68106 BY ARCHBISHOP GERALD T. BERGAN (402) 556-1456 • www.stmomaha.org Pastor ....................... Rev. Frank Baumert e-mail ........................................ [email protected] Phone……………………………………402 -677-1565 Deacons ...................... Allan Schumacher and Matt Wolbach Mass Schedule Weekend Saturday (vigil) .................................................................. 5:00 pm Sunday ....................................................... 8:00 am and 10:30 am Weekday Monday-Friday ................................................................. 7:00 am Tuesday & Friday —Usually (School Mass)..................8:15 am Confessions: Saturday..................................................................... 4:00-4:40 pm Baptism and Matrimony Please contact the parish office for information Pastoral Staff Business Manager .......................................... Nancy Williams e-mail ....................................... [email protected] Parish Secretary .................................................... Patty Settles e-mail.................................psettles@stm.omhcoxmail.com Pastoral Assistant………………..Sister Pauline Schwandt e- mail………………….…[email protected] Parish Office Hours .................... …..M -F 8:00 am —4:30 pm (Closed Noon —1:00 pm) Parish Office Phone ........................................... (402) 556-1456 Parish Office Fax ................................................ (402)