Rising from the Ashes: Remaking Community Around Conflict and Coal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARAMILITARIES Kill Suspected Supporters of the FARC

UniTeD SelF-DeFenSe FoRCeS oF ColoMBiA (AUC) PARAMiliTARY TRooPS, lA GABARRA, noRTe De SAnTAnDeR, DeCeMBeR 10, 2004 PARAMiliTARieS kill suspected supporters of the FARC. By 1983, locals reported DEATh TO KIDNAPPERs cases of army troops and MAS fighters working together to assas- sinate civilians and burn farms.5 After the 1959 Cuban revolution, the U.S. became alarmed power and wealth, to the point that by 2004 the autodefensas had this model of counterinsurgency proved attractive to the Colom- that Marxist revolts would break out elsewhere in latin Ameri- taken over much of the country. bian state. on a 1985 visit to Puerto Boyacá, President Belisario Be- ca. in 1962, an Army special warfare team arrived in Colombia to As they expanded their control across Colombia, paramil- tancur reportedly declared, “every inhabitant of Magdalena Medio help design a counterinsurgency strategy for the Colombian armed itary militias forcibly displaced over a million persons from the has risen up to become a defender of peace, next to our army, next to forces. even though the FARC and other insurgent groups had not land.3 By official numbers, as of 2011, the autodefensas are estimat- our police… Continue on, people of Puerto Boyacá!”6 yet appeared on the scene, U.S. advisers recommended that a force ed to have killed at least 140,000 civilians including hundreds of Soon, landowners, drug traffickers, and security forces set made up of civilians be used “to perform counteragent and coun- trade unionists, teachers, human rights defenders, rural organiz- up local autodefensas across Colombia. in 1987, the Minister of terpropaganda functions and, as necessary, execute paramilitary, ers, politicians, and journalists who they labelled as sympathetic government César gaviria testified to the existence of 140 ac- sabotage, and/or terrorist activities against known communist pro- to the guerrillas.3 tive right-wing militias in the country.7 Many sported macabre ponents. -

Departamento De La Guajira

73°30'W 73°00’W 72°30'W 72°00’W 71°30'W 12°30'N 12°30'N Punta Gallinas Punta Taroa Punta Paranturero Taroa Bahía Punta Taroita Punta Aguja p Hondita Punta Huayapaín o r Bahía i Punta Shuapia r E Honda a Puerto M . Estrella Cabo y A B ÎPuerto San José de Aeropuerto Chichibacoa Punta Media Luna Bolívar Bahía Honda Puerto Estrella I Ensenada Aipía Bahía Shakcu ho Ensenada Musich Portete sta Ma Nazareth R Cabo de Puerto Portete Ay. A y Cerro Rumo La Vela . Y uo Serranía de Macuira u ir A r ár y. u A ar A J y. J Guarerpá Irraipá a a * p A sc y h u PARQUE NACIONAL NATURAL . Pararapu i a Punta n A SERRANÍA DE MACUIRA A a Serraníay Carpintero. y Espada C Ic . Carrizal h p A i k e r A i 12°00’N Taparajín t y Guarpana 12°00’N Punta Solipa a . Serranía j Ay. a J K i a a de Simarua n Puerto iv r a a h Morro López R El Cardón n a n A o i de Sakaralahu y. e M h Salina Umakaja r u Bahía Tukakas a o r i e r n Punta Semescre u ai ap s Ay. Jihichi a Jojoncito J . K Punta Mushippa . Ay A y Ay Bahía Cocinetas A . J Salina de Manaure Aeropuerto Serranías de Cocinas ep A Cerro í Manaure y Boca de San Agustín . La Teta Manaure M A Cerro Ipuana Salina de San Juan y. -

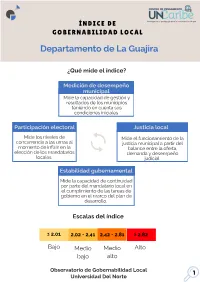

Gobernabilidad Local En La Guajira

ÍNDICE DE GOBERNABILIDAD LOCAL Departamento de La Guajira ¿Qué mide el índice? Medición de desempeño municipal Mide la capacidad de gestión y resultados de los municipios teniendo en cuenta sus condiciones iniciales Participación electoral Justicia local Mide los niveles de Mide el funcionamiento de la concurrencia a las urnas al justicia municipal a partir del momento de influir en la balance entre la oferta, elección de los mandatarios demanda y desempeño locales judicial Estabilidad gubernamental Mide la capacidad de continuidad por parte del mandatario local en el cumplimiento de las tareas de gobierno en el marco del plan de desarrollo. Escalas del índice ≤ 2,01 2,02 - 2,41 2,42 - 2,81 ≥ 2,82 Bajo Medio Medio Alto bajo alto Observatorio de Gobernabilidad Local 1 Universidad Del Norte Departamento de La Guajira Población: 985.452 de habitantes Extensión territorial: 20.848 Km2 División político-administrativa: 15 municipios La Guajira posee unas dinámicas territoriales caracterizadas por altos niveles de ruralidad y dispersión demográfica Índice de Gobernabilidad Local BAJO MEDIO BAJO MEDIO ALTO ALTO Barrancas, Dibulla, Maicao, Distracción, Manaure, Albania, El Molino Fonseca, La Jagua del Riohacha, y Hatonuevo. Pilar, San Juan del Uribia y Urumita. Cesar y Villanueva Observatorio de Gobernabilidad Local 2 Universidad Del Norte Resultados por municipio El municipio con el Índice de Gobernabilidad Local más bajo son Dibulla, Riohacha, Uribia y Urumita. Por el contrario, Albania, El Molino y Hatonuevo obtuvieron los resultados más altos -

Uso Y Manejo De Las Regalías La Guajira 2012-2015

Uso y manejo de las regalías La Guajira 2012-2015 Noviembre de 2016 1 República de Colombia Contraloría María Isabel Solano Rondón General de la República Juan Miguel Tawil Henao Profesionales Grupo Control Fiscal Edgardo José Maya Villazón Macro - Regalías Contralor General de la República Gloria Amparo Alonso Masmela Edición de texto y mapas Vicecontralora General de la República Maria Ximena O’Byrne Agredo Juan Carlos Rendón López Asesoría Técnica Contralor Delegado Intersectorial Antonio Hernández Gamarra Coordinador Grupo Control Fiscal -Micro David Isaac Botero Comunicaciones y Publicaciones Maria Juliana Uribe Guzmán Contralores Delegados Intersectoriales Directora Oficina de Comunicaciones y Regalías – Grupo de Control Fiscal Macro Publicaciones Rossana Payares Altamiranda Elaboración y revisión del informe: Amanda Granados Urrea Nombre Funcionario (s) Contralora Delegada Intersectorial Coordinadora Grupo Control Fiscal Macro Diagramación, elaboración de gráficos, de Regalias edición fotográfica Nombre de los funcionarios Participaron: Alexandra Acosta Herrera César Augusto Ocampo Sierra Contraloría General de la República Angélica Páez Vargas (Dirección) Maddy Elena Perdomo Tejada PBX: 647 7000 1 Bogotá D.C., Colombia Noviembre de 2016 ww 1 Tabla de contenido Lista de Siglas .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Introducción ................................................................................................................................................ -

Codificación De Municipios Por Departamento

Código Código Municipio Departamento Departamento Municipio 05 001 MEDELLIN Antioquia 05 002 ABEJORRAL Antioquia 05 004 ABRIAQUI Antioquia 05 021 ALEJANDRIA Antioquia 05 030 AMAGA Antioquia 05 031 AMALFI Antioquia 05 034 ANDES Antioquia 05 036 ANGELOPOLIS Antioquia 05 038 ANGOSTURA Antioquia 05 040 ANORI Antioquia 05 042 ANTIOQUIA Antioquia 05 044 ANZA Antioquia 05 045 APARTADO Antioquia 05 051 ARBOLETES Antioquia 05 055 ARGELIA Antioquia 05 059 ARMENIA Antioquia 05 079 BARBOSA Antioquia 05 086 BELMIRA Antioquia 05 088 BELLO Antioquia 05 091 BETANIA Antioquia 05 093 BETULIA Antioquia 05 101 BOLIVAR Antioquia 05 107 BRICEÑO Antioquia 05 113 BURITICA Antioquia 05 120 CACERES Antioquia 05 125 CAICEDO Antioquia 05 129 CALDAS Antioquia 05 134 CAMPAMENTO Antioquia 05 138 CAÑASGORDAS Antioquia 05 142 CARACOLI Antioquia 05 145 CARAMANTA Antioquia 05 147 CAREPA Antioquia 05 148 CARMEN DE VIBORAL Antioquia 05 150 CAROLINA Antioquia 05 154 CAUCASIA Antioquia 05 172 CHIGORODO Antioquia 05 190 CISNEROS Antioquia 05 197 COCORNA Antioquia 05 206 CONCEPCION Antioquia 05 209 CONCORDIA Antioquia 05 212 COPACABANA Antioquia 05 234 DABEIBA Antioquia 05 237 DON MATIAS Antioquia 05 240 EBEJICO Antioquia 05 250 EL BAGRE Antioquia 05 264 ENTRERRIOS Antioquia 05 266 ENVIGADO Antioquia 05 282 FREDONIA Antioquia 05 284 FRONTINO Antioquia 05 306 GIRALDO Antioquia 05 308 GIRARDOTA Antioquia 05 310 GOMEZ PLATA Antioquia 05 313 GRANADA Antioquia 05 315 GUADALUPE Antioquia 05 318 GUARNE Antioquia 05 321 GUATAPE Antioquia 05 347 HELICONIA Antioquia 05 353 HISPANIA Antioquia -

La Alianza De Paramilitares Y Polticos En Colombia

1 LA ALIANZA DE PARAMILITARES Y POLÍTICOS EN COLOMBIA Revista Semana Noviembre 2006 Un genio del mal La maquinaria que 'Jorge 40' montó a sangre y fuego en Cesar resultó un fenómeno asombroso de eficiencia electoral. SEMANA estuvo en este departamento, que lucha por reponerse de los embates de la violencia. Cuando estalló la crisis de la parapolítica, en Valledupar no hubo sorpresa. "Eso estaba visto. Tan visto, que hasta Leandro Díaz lo había visto", dice la gente en la calle. El viejo Leandro Díaz es un venerado compositor vallenato, ciego. Y es que los paramilitares empezaron a controlar la política ante los ojos de todos. Abiertamente, los paramilitares crearon distritos electorales y candidaturas únicas. De frente, obligaron a renunciar a los aspirantes y funcionarios que no les servían. Sin necesidad de esconderse, han defraudado la salud, las obras públicas y las regalías. La historia de la política en Cesar, en los últimos años, está unida a la historia sobre cómo 'Jorge 40' construyó su imperio. Una historia llena de ambición, corrupción, impunidad, traición y muerte, que empezó dos décadas atrás. En los años 80 las más importantes familias de Cesar, los Araújo, los Castro, los Pupo, entre otras, se encontraron, de la noche a la mañana, frente a la crisis económica. La caída del algodón los afectó a todos. "La gente de la plaza", como se les conoce en Valledupar, porque sus enormes caserones rodean la plaza Alfonso López, no sólo estaban endeudadas hasta el cuello, sino que empezó a esfumarse la influencia política que otrora gozaron. El Cesar, que durante años puso ministros, embajadores y congresistas, estaba completamente rezagado. -

Colombia's New Armed Groups

COLOMBIA’S NEW ARMED GROUPS Latin America Report N°20 – 10 May 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. MORE THAN CRIMINAL GANGS?.......................................................................... 2 A. THE AUC AS PREDECESSOR ..................................................................................................3 B. THE NEW ILLEGAL ARMED GROUPS ......................................................................................6 III. CASE STUDIES.............................................................................................................. 8 A. NORTE DE SANTANDER .........................................................................................................8 1. AUC history in the region..........................................................................................8 2. Presence of new illegal armed groups and criminal organisations ..............................8 3. Conflict dynamics....................................................................................................10 4. Conclusion ...............................................................................................................11 B. NARIÑO ..............................................................................................................................11 1. AUC history in the region........................................................................................11 -

Ley 2072 Del 31 De Diciembre De 2020

"POR LA CUAL SE DECRETA EL PRESUPUESTO DEL SISTEMA GENERAL DE REGALíAS PARA EL BIENIO DEL 1° DE ENERO DE 2021 AL 31 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2022" EL CONGRESO DE COLOMBIA DECRETA: TíTULO I PRESUPUESTO DE INGRESOS DEL SISTEMA GENERAL DE REGALíAS ARTícu lO 1. Presupuesto de ingresos del Sistema General de Regalías. Establézcase el presupuesto de ingresos del Sistema General de Regalías para el bienio del 1° de enero de 2021 al 31 de diciembre de 2022, en la suma de QUINCE BillONES CUATROCIENTOS VEINTISIETE Mil QUINIENTOS NOVENTA Y SIETE MilLONES QUINIENTOS SETENTA MIL CIENTO NOVEf"HA y TRES PESOS MONEDA LEGAL ($15.427.597.570 .193), según el siguiente detalle: Nivel Subnivel Nível3 Concepto Nível5 Ingreso Valor rentístico rentistico INGRESOS CORRIENTES 15.427.597.570.193 02 INGRESOS NO TRIBUTARIOS 15.427.597.570.193 DERECHOS ECONÓMICOS POR USO DE 02 4 15.427.597 .570.193 RECURSOS NATURALES 02 4 01 REGALlAS 15.427.597.570.193 02 4 01 01 HIDROCARBUROS 12.289.929.995.268 02 4 01 02 MINERALES 3.137.667.574.925 TíTULO 11 PRESUPUESTO DE GASTOS DEL SISTEMA GENERAL DE REGALíAS CAPíTULO I MONTO TOTAL DEL PRESUPUESTO DE GASTOS DEL SISTEMA GENERAL DE REGALíAS 1 () n I~) ) r.." <. , ,_ ARTíCULO 2. Presupuesto de gastos del Sistema General de Regalías. Establézcase el presupuesto de gastos con cal'go al Sistema General de Regalías durante el bienio del1 ° de enero de 2021 al31 de diciembre de 2022, en la suma de QUINCE BILLONES CUATROCIENTOS VEINTISIETE MIL QUINIENTOS NOVENTA Y SIETE MILLONES QUINIENTOS SETENTA MIL CIENTO NOVENTA Y TRES PESOS MONEDA LEGAL ($15.427.597.570 .193). -

La Guajira En Su Laberinto Transformaciones Y Desafios De La Violencia

La Fundación Ideas para la Paz (FIP) es un centro de pensamiento creado en 1999 por un grupo de empresarios colombianos. Su misión es generar conocimiento de manera objetiva y proponer iniciativas que contribuyan a la superación del conflicto armado en Colombia y a la construcción de una paz sostenible, desde el respeto por los derechos humanos, la pluralidad y la preeminencia de lo público. La FIP con independencia se ha propuesto como tarea central contribuir de manera eficaz a la comprensión de todos los escenarios que surgen de los conflictos en Colombia, en particular desde sus dimensiones política, social y militar. Como centro de pensamiento mantiene la convicción de que el conflicto colombiano necesariamente concluirá con una negociación o una serie de negociaciones de paz que requerirán la debida preparación y asistencia técnica. Como parte de su razón de ser llama la Informes FIP atención sobre la importancia de preparar al país para escenarios de postconflicto. La Guajira en su laberinto transformaciones y desafios de la violencia Gerson Iván Arias Milena Peralta Carolina Serrano Carlos Prieto Miguel Ortega Carol Barajas Joanna Rojas Roa Agosto de 2011 Fundación Ideas para la paz La Guajira en su laberinto transformaciones y desafios de la violencia Gerson Iván Arias Milena Peralta Carolina Serrano Carlos Prieto Miguel Ortega Carol Barajas Joanna Rojas Roa Agosto de 2011 Serie Informes No. 12 2 • www.ideaspaz.org/publicaciones • Contenido La Guajira en su laberinto transformaciones y desafios de la violencia 4 1. Introducción 5 2. Contexto geográfico e histórico 6 2.1. Contrabando y contexto de la ilegalidad en La Guajira 8 2.2. -

Report 2019 Cerrejón's Sustainability Report 2019

CERREJÓN'S SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2019 CERREJÓN'S SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2019 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2019 3 ABOUT THIS REPORT “Our 2019 Sustainability Report is a reflection of our GUIDELINES. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) commitment to transparency and accountability with all standards, Core option. our audiences. This is the fifteenth report we have presented since we subscribed to the United Nations SCOPE. This report documents the management of the Global Compact initiative in 2005. This document presents companies Carbones del Cerrejón Limited (a 100% our main results and challenges in ten principles related to privately owned foreign company domiciled in Anguilla, human rights, labour standards, the environment, and British West Indies) and Cerrejón Zona Norte S.A. (a anti-corruption practices”. 100% privately owned Colombian limited liability company Claudia Bejarano, CEO (i) of Cerrejón. domiciled in Bogotá) (both hereinafter Cerrejón). PERIOD. January 1 to December 31 of 2019. VERSION. This report is the fifteenth that we have submitted yearly without interruption since 2005 as part of our commitment to the United Nations Global Compact. ASSEMBLY. Cerrejón Communications Division. DESIGN: TBWA. HEADQUARTERS AND CONTACT Albania, La Guajira 57 5 350 5555 Bogotá D.C. Calle 100 no. 19 – 54 Edificio Prime Tower 57 1 5955555 [email protected] www.cerrejon.com Any changes in the company or our supply chain as well as any alterations in how the information is presented compared to the 2018 report will be detailed in each of -

ANEXO No.05 LUGAR DE EJECUCIÓN

ANEXO No.05 LUGAR DE EJECUCIÓN DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO O ZONA CUNDINAMARCA ANAPOIMA CUNDINAMARCA BOJACA CUNDINAMARCA CAJICA CUNDINAMARCA CHIA CUNDINAMARCA COTA CUNDINAMARCA FACATATIVA CUNDINAMARCA FUNZA CUNDINAMARCA FUSAGASUGA CUNDINAMARCA GIRARDOT CUNDINAMARCA GUADUAS CUNDINAMARCA LA CALERA CUNDINAMARCA LA MESA CUNDINAMARCA MADRID CUNDINAMARCA MESITAS CUNDINAMARCA SOACHA CUNDINAMARCA SOPO CUNDINAMARCA SUESCA CUNDINAMARCA TOCANCIPA CUNDINAMARCA UBATE CUNDINAMARCA VILLETA CUNDINAMARCA ZIPAQUIRA DISTRITO CAPITAL ALQUERIA DISTRITO CAPITAL BARRIOS UNIDOS DISTRITO CAPITAL BOSA DISTRITO CAPITAL CENTENARIO DISTRITO CAPITAL CHAPINERO DISTRITO CAPITAL CIUDAD BOLIVAR DISTRITO CAPITAL COLINAS DISTRITO CAPITAL FONTIBON DISTRITO CAPITAL GRANADA HILLS DISTRITO CAPITAL KENEDY DISTRITO CAPITAL LA TRINIDAD O LA PRADERA DISTRITO CAPITAL NOR-OCCIDENTE DISTRITO CAPITAL RESTREPO DISTRITO CAPITAL SUBA DISTRITO CAPITAL TEUSAQUILLO DISTRITO CAPITAL TOBOERIN DISTRITO CAPITAL VENECIA DISTRITO CAPITAL ZONA NORTE TOLIMA MELGAR BOYACA AQUITANIA BOYACA CHIQUINQUIRA BOYACA DUITAMA BOYACA PAIPA BOYACA SOGAMOSO BOYACA TUNJA CAQUETA FLORENCIA CASANARE YOPAL HUILA GARZON HUILA LA PLATA HUILA NEIVA HUILA PITALITO Página 1de4 ANEXO No.05 LUGAR DE EJECUCIÓN DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO O ZONA META ACACIAS META GRANADA META VILLAVICENCIO TOLIMA ESPINAL TOLIMA HONDA TOLIMA IBAGUE TOLIMA LERIDA TOLIMA PURIFICACION CALDAS AGUADAS CALDAS ANSERMA CALDAS CHINCHINA CALDAS LA DORADA CALDAS MANIZALES CALDAS MANZANARES CALDAS NEIRA CALDAS PALESTINA CALDAS RIOSUCIO CALDAS SALAMINA CALDAS SUPIA -

En El Siguiente Listado Encuentra La Entidad En La Cual Debe Cobrar Su Subsidio De Acuerdo Al Municipio Al Que Pertenezca

EN EL SIGUIENTE LISTADO ENCUENTRA LA ENTIDAD EN LA CUAL DEBE COBRAR SU SUBSIDIO DE ACUERDO AL MUNICIPIO AL QUE PERTENEZCA. Nota: para buscar presione las teclas Control F y en la ventana que sale escriba el nombre de su municipio DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO ENTIDAD PAGADORA AMAZONAS EL ENCANTO Matrix Giros y Servicios AMAZONAS LA CHORRERA Matrix Giros y Servicios AMAZONAS LETICIA Matrix Giros y Servicios AMAZONAS PUERTO NARINO Matrix Giros y Servicios AMAZONAS TARAPACA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA ABEJORRAL Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA ABRIAQUI Efecty ANTIOQUIA ALEJANDRIA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA AMAGA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA AMALFI Efecty ANTIOQUIA ANDES Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA ANGELOPOLIS Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA ANGOSTURA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA ANORI Efecty ANTIOQUIA ANZA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA APARTADO Efecty ANTIOQUIA ARBOLETES Efecty ANTIOQUIA ARGELIA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA ARMENIA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA BARBOSA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA BELLO Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA BELMIRA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA BETANIA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA BETULIA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA BRICENO Efecty ANTIOQUIA BURITICA Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA CACERES Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA CAICEDO Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA CALDAS Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA CAMPAMENTO Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA CANASGORDAS Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA CARACOLI Matrix Giros y Servicios ANTIOQUIA