Community Engagement As Input to the Design of the Environmental Center at Frick Park and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITY of PITTSBURGH 2020 Capital Budget & Six Year Plan

CITY OF PITTSBURGH 2020 Capital Budget & Six Year Plan Pittsburgh City Council As approved by City Council December 17, 2019 City of Pittsburgh City Council Members Bruce A. Kraus, President District 3 Darlene M. Harris, Human Resources District 1 Theresa Kail-Smith, Public Works District 2 Anthony Coghill, Urban Recreation District 4 Corey O’Connor, Intergovernmental Affairs District 5 R. Daniel Lavelle, Public Safety District 6 Deborah L. Gross, Land Use & Economic Development District 7 Erika Strassburger, Performance and Asset Management District 8 Rev. Ricky V. Burgess, Finance & Law District 9 City Council Budget Office Bill Urbanic, Budget Director Michael Strelic, Budget Manager Office of the City Clerk Brenda Pree, City Clerk Kimberly Clark-Baskin, Assistant City Clerk Special thanks to Chief Schubert for the cover Additional thanks to Mayor Bill Peduto, City Controller Michael Lamb, the Mayor’s Budget Office staff, and the many citizens who participated through the process Special thanks to Valerie Jacko for design and printing services. Visit us on the web at: www.pittsburghpa.gov 2020 Project Summary 2020 Project Summary Page Project Name 2020 Budget Functional Area: Engineering and Construction 18 28TH STREET BRIDGE (TIP) 250,000 ADVANCED TRANSPORTATION AND CONGESTION MANAGEMENT 20 3,492,571 TECHNOLOGIES DEVELOPMENT (ATCMTD) 22 BRIDGE UPGRADES 4,396,476 24 BUS RAPID TRANSIT - 26 CBD SIGNAL UPGRADES (TIP) - 28 CHARLES ANDERSON BRIDGE (TIP) - 30 COMPLETE STREETS 17,722,742 32 DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION, AND INSPECTION SERVICES 244,011 -

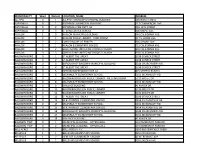

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION NAME ADDRESS

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION_NAME ADDRESS ALEPPO 0 1 ALEPPO TOWNSHIP MUNICIPAL BUILDING 100 NORTH DRIVE ASPINWALL 0 1 ASPINWALL MUNICIPAL BUILDING 217 COMMERCIAL AVE. ASPINWALL 0 2 ASPINWALL FIRE DEPT. #2 201 12TH STREET ASPINWALL 0 3 ST SCHOLASTICA SCHOOL 300 MAPLE AVE. AVALON 1 0 AVALON MUNICIPAL BUILDING 640 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 2 1 AVALON PUBLIC LIBRARY - CONF ROOM 317 S. HOME AVE. AVALON 2 2 LORD'S HOUSE OF PRAYER 336 S HOME AVE AVALON 3 1 AVALON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 721 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 2 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 3 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 1 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 2 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 3 BOROUGH OF BALDWIN MUNICIPAL BUILDING 3344 CHURCHVIEW AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 4 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 5 OPTION INDEPENDENT FIRE CO 825 STREETS RUN RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 6 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 7 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY - MEETING ROOM 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 8 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 9 WALLACE BUILDING 41 MACEK DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 10 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 11 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 12 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 13 W.R. PAYNTER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3454 PLEASANTVUE DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 14 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 15 W.R. -

Currents Newsletter

September 2019 NEW AGREEMENT WITH DEP SETS COURSE FOR PITTSBURGH’S WATER FUTURE IN THIS ISSUE: 1 DEP Consent Order In September 2019, our Board of 2 RAW Talk Directors authorized Executive Director Robert Weimar to sign a 3 PWSA in the Community Consent Order and Agreement with the Pennsylvania 5 PWSA in the News Department of Environmental 6 Team PWSA Protection (DEP) to restore 9 Engineering & functionality and water system Construction resiliency as well as modernize our infrastructure. The signed 10 Water Wise agreement will ultimately result 11 PWSA Connect in critical upgrades to our aging water distribution system that COMING UP: serves approximately 520,000 people in the Pittsburgh area. 2019 Board Meetings October 25 Projects identified in November 22 the agreement include: December 20 Rehabilitating or replacing Meetings begin at 10:00 am two rising water mains to at 1200 Penn Avenue and are the Highland 2 Reservoir in open to the public. Highland Park, replacing the Water treatment infrastructure at the Highland 1 Reservoir Microfiltration Plant. cover and liner of the Highland Riverview Park Day - Stormwater Outreach 2 Reservoir, constructing a disinfection required by state We are pleased to work new rising water main from September 29 and federal regulations. collaboratively with DEP to Riverview Park; the Aspinwall Pump Station place us on a firm path toward to the Lanpher Reservoir in Ensuring the quality, reliability, 1:00 - 5:00 pm and safety of our water is renewing our infrastructure by Shaler Township, rehabilitating prioritizing our critical projects. or replacing the Aspinwall our number one priority. -

Performance Audit

. Performance Audit Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy Report by the Office of City Controller MICHAEL E. LAMB CITY CONTROLLER Douglas W. Anderson, Deputy Controller Gloria Novak, Performance Audit Manager Bette Ann Puharic, Performance Audit Assistant Manager Joanne Corcoran, Performance Auditor Emily Ferri, Performance Auditor Bill Vanselow, Performance Auditor July 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i-iv Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 Overview .........................................................................................................................................4 Objectives........................................................................................................................................5 Scope and Methodology .................................................................................................................6 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS PPC Financial Data........................................................................................................................8 PPC Revenues ..................................................................................................................8 PPC Expenses ..................................................................................................................9 PPC Assets. ....................................................................................................................10 -

Homewood-East-Liberty-Point-Breeze

STEEL INDUSTRY HERITAGE CORPORATION ETHNOGRAPHIC SURVEY 1993 FINAL REPORT HOMEWOOD, POINT BREEZE, EAST LIBERTY AND HIGHLAND PARK Jean E. Snyder 28 October 1993 Table of Contents 2 I. Introduction and Fieldwork Plan 3 II. Neighborhood Survey 5 A. Homewood-Brushton 5 1. Shifting settlement patterns 2. Images of the past 3. Perspectives on the present 4. Cultural traditions and events 5. Visions for the future B. Point Breeze 26 1. Shifting settlement patterns 2. Connections to Homewood 3. Neighborhood units 4. Cultural traditions and events 5. Visions for the future C. East Liberty 35 1. Shifting settlement patterns 2. Images of the past 3. Perspectives on the present 4. Cultural traditions and events 5. Visions for the future D. Highland Park 47 III. Conclusions and suggestions for future research 48 IV. Appendices 52 A. Primary Contacts: Formal interviews, taped B. Primary Contacts: Informal interviews, not taped C. Contacts List D. Bibliography I. Introduction and Fieldwork Plan In their history and in their present populations the neighborhoods surveyed in this project reflect 3 Pittsburgh's social, economic and ethnic diversity. Homewood, Point Breeze, East Liberty and Highland Park boast a vibrant, almost mythical past of economic vitality--even abundance--now recalled with nostalgia by residents and former residents. The shifting patterns of ethnic populations in these neighborhoods reflect the currents created by the rise and fall of the steel industry in Western Pennsylvania. In some cases, because residents worked directly in the mills or related industries; other groups were affected less directly, but through their involvement in local and state government, industrial and mercantile construction, and the development of Pittsburgh's transportation infrastructure. -

Polling Places General 2020 1 Pending

POLLING PLACES GENERAL 2020 MUNICIPALITY MUNI W D LOCATION As of September 9, 2020 ORANGE FILL indicates polling place change since the November 2019 election ALEPPO 102 0 1 ALEPPO TOWNSHIP MUNICIPAL BUILDING- 100 NORTH DRIVE ASPINWALL 102 0 1 ASPINWALL MUNICIPAL BUILDING- 217 COMMERCIAL AVE. ASPINWALL 102 0 2 ASPINWALL FIRE DEPT. #2- 201 12TH STREET ASPINWALL 102 0 3 ST SCHOLASTICA SCHOOL- 300 MAPLE AVE. AVALON 103 1 0 AVALON MUNICIPAL BUILDING- 640 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 103 2 1 AVALON PUBLIC LIBRARY- CONF ROOM- 317 S. HOME AVE. AVALON 103 2 2 EPIPHANY CHURCH 1ST FLOOR 1012 CALIFORNIA AVE AVALON 103 3 1 AVALON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL- 721 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 103 3 2 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH- 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 103 3 3 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH- 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. BALDWIN BORO 104 0 1 ST ALBERT THE GREAT- 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 104 0 2 ST ALBERT THE GREAT- 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 104 0 3 BOROUGH OF BALDWIN MUNICIPAL BUILDING- 3344 CHURCHVIEW AVE. BALDWIN BORO 104 0 4 ST ALBERT THE GREAT- 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 104 0 5 OPTION INDEPENDENT FIRE CO- 825 STREETS RUN RD. BALDWIN BORO 104 0 6 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL- 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 104 0 7 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY-MEETING ROOM-5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 104 0 8 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL- 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 104 0 9 WALLACE BUILDING- 41 MACEK DR. BALDWIN BORO 104 0 10 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY-5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 104 0 11 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY-5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 104 0 12 ST ALBERT THE GREAT- 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 104 0 13 W.R. -

2012 Regional Park Master Plan

REGIONAL PARKS MASTER PLAN 2012 UPDATE Envisioning the Historic Regional Parks as cornerstones of a vibrant parks and open space system for a sustainable 21st century city nov. 2014 A Partnership of the City of Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1 chapter 4: the plan 21 Purpose of Master Plan Update 5 A City Wide System 21 Acknowledgements 6 System Recommendations 21 System-Wide Policies 25 Key Policies 25 chapter 1: reviewing past work 7 Common Solutions 26 Summary of 2000 Stewardship Plan 7 Accomplishments of PPC and Partners 7 Key Studies 8 Building on Momentum 9 chapter 5: the recommendations 29 Defining the System 29 chapter 2: the vision 11 A Regional Approach to the Envisioning Our Parks and Boulevards 11 City-Wide System 29 Trends and challenges 11 Frick Park 30 Parks and Community Transformation 14 Highland Park 34 A New Vision of Integrated Sustainability 15 Riverview Park 38 Park Systems- Blue, Green, and Gray 17 Schenley Park 42 A Foundation of Values and Principles 18 chapter 6: ensuring sustainability 47 chapter 3: the strategy 19 Strategies to Achieve Enduring Improvements 47 Building Blocks for Change 19 Design and Performance Standards 47 Innovative Planning Strategies 19 Resources 21 INTRODUCTION A core value of life in Pittsburgh is the abun- component of PLANPGH. Th e Parks Conservancy has self-funded this eff ort, re-engaging the original professional team from the 2000 Master Plan. dance of parks set among green hillsides and Led by LaQuatra Bonci Associates, in conjunction with Heritage Landscapes, fl owing rivers. -

Allocation Scenarios

PAGE 1 OF 3 Capital Project Allocation Scenarios Sites are ordered by their Final Investment Priority Rank, which is based on their Community and Park Need Scores. Sites that include one or more nearby parks in the column "Consider with these nearby sites" may be considered as a single unit, with investment directed towards the park that is best positioned to serve the community's preferences. "Passive Sites" and Greenways are not included in this list. These are sites that lack significant amenities or have been targeted for naturalization; thus they should not receive Capital Project investments. For a list of "Passive Sites" and Greenways, see the Park Scoring Database. The Investment Priority Score will be recalculated annually based on new demographic data and information about recent park investments. As a result, the Investment Priority Ranking may shift if park or community conditions change. * All allocations are escalated to year-of-implementation dollars, assuming 2.1% annual inflation. Projects that are not assigned a year are listed in 2020 dollars. Site name Consider with these nearby Investment Type Size (acres) Final Final Total Existing City Grants Estimated Project Year 1 sites Investment Investment City CIP (Confirmed) Pittsburgh Parks Priority Score Priority Rank 2019-2024 For All (Planned) Allocation All Categories (Rounded Figures) Baxter Park Partial Makeover 2.4 724 1 $150,000 $0 $3,064,000 2020 McKinley Park Partial Makeover 78.5 673 2 $150,000 $0 $11,154,000 2020 Spring Hill Park Full Transformation 6.4 671 3 -

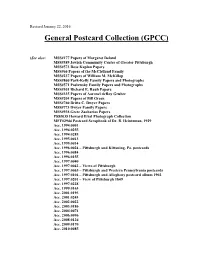

Postcard Collection Library

Revised January 22, 2016 General Postcard Collection (GPCC) (See also: MSS#177 Papers of Margaret Deland MSS#389 Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh MSS#573 Rose Kaplan Papers MSS#66 Papers of the McClelland Family MSS#237 Papers of William M. McKillop MSS#860 Park-Kelly Family Papers and Photographs MSS#571 Paslawsky Family Papers and Photographs MSS#301 Richard E. Rauh Papers MSS#335 Papers of Aaronel deRoy Gruber MSS#204 Papers of Bill Green MSS#760 Britta C. Dwyer Papers MSS#773 Dwyer Family Papers MSS#938 Grete Zacharias Papers PSS#035 Howard Etzel Photograph Collection MFF#2944 Postcard Scrapbook of Dr. B. Heintzman, 1929 Acc. 1994.0001 Acc. 1994.0255 Acc. 1994.0285 Acc. 1995.0013 Acc. 1995.0014 Acc. 1996.0024 – Pittsburgh and Kittaning, Pa. postcards Acc. 1996.0084 Acc. 1996.0155 Acc. 1997.0040 Acc. 1997.0042 – Views of Pittsburgh Acc. 1997.0065 – Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania postcards Acc. 1997.0104 – Pittsburgh and Allegheny postcard album 1902 Acc. 1997.0201 – View of Pittsburgh 1849 Acc. 1997.0228 Acc. 1999.0163 Acc. 2001.0195 Acc. 2001.0243 Acc. 2002.0022 Acc. 2003.0186 Acc. 2004.0074 Acc. 2006.0096 Acc. 2008.0126 Acc. 2009.0170 Acc. 2010.0085 Postcard Collection Inventory, Page # 2 of 81 Acc. 2011.0171 – Interesting Views of Pittsburgh postcard book Acc. 2011.0218 – Pittsburgh and Western Pa. Acc. 2011.0292 – Gateway Center, Point, Downtown Acc. 2014.0017) (Book Resources: Search Postcard History Series in catalog Greetings from Pittsburgh: A Picture Postcard History/Ralph Ashworth - F159.3.P643 A84 1992 q A Pennsylvania Album: picture postcards 1900-1930/George Miller - F150.M648 long Riverlife: Postcards from the Rivers/Riverlife Task Force – HT177 .P5 P6 2002 long Box 1 Pittsburgh Aviaries Conservatory Aviary Churches All Saints Episcopal- Allegheny Bethany Evangelical Lutheran- East Liberty Bethel Presbyterian Calvary Episcopal – Shady/Walnut Calvary United Methodist – North Side Christ Evangelical Lutheran-East End Christ Church of the Ascension – Ellsworth & Neville Christ M.E. -

January 2018

the bar Back issues from 2000 to the present and a comprehensive, searchable index are available THE NEWSLETTER OF THE online at www.westbar.org/thesidebar. sideWESTMORELAND BAR ASSOCIATION VOLUME XXIX, NUMBER 6 JANUARY 2018 The End of An Era Editor’sReflections note: The Hon. Richard E. McCormick, on Jr., retired fromMy the Court Career of Common Pleas of Westmoreland County effective January 8, 2018, after twenty-seven years on the bench. He is continuing as a Senior Judge. My Kemo by The Hon. Richard E. McCormick, Jr. the lawyers and judges who inhabited Sabe those courtrooms, back when the trial ou might say I was raised in the was more often a means where disputes by Beth Orbison, Esq. Courthouse. and accusations and passions were When my Dad was elected by resolved. This is where majesty and uesday, January 9, 2018, marked Y the end of an era: it was the the Judges and the voters to be District absurdity met in the matters of the first day in 52 years that a Attorney and Judge, we (all eight of T theft of a $1.50 hoagie. I’m still not Richard E. McCormick was not sitting us eventually) were often told to go sure whether the Honorable Donetta on the bench of the Court of Common to a doctor or dentist Ambrose was overcome Pleas of Westmoreland County. appointment after school with hysterical laughter at Following in the footsteps of his and then meet our Dad the price, or the prosecutor’s father and namesake, Judge Richard at the Courthouse for a mispronunciation of the E. -

George Westinghouse Engineer & Entrepreneur

GEORGE WESTINGHOUSE ENGINEER & ENTREPRENEUR by Brian Roberts, CIBSE Heritage Group George Westinghouse, 1846 - 1914 George Westinghouse was born on the 6 th October, 1846, in Central Bridge, New York, the son of George Westinghouse Sr. and Emiline (Vedder). He was eighth out of ten children. His father was the owner of a machine shop and this probably the reason why son George was talented with machinery and in business The young George Westinghouse Junior Central Bridge, New York, birt hplace of George Westinghouse George Westinghouse Senior and his wife Emiline The Schenectady Agricultural Works o f George Westinghouse (Senior) He was 15 when the Civil War broke out and he enlisted in the New York National Guard until h is parents convinced him to return home. In April 1863, his parents allowed him to re - enlist and he joined Company M of the 16 th New York Cavalry, earning promotion to Corporal. In December 1864, he resigned and joined the Navy where he served as Acting Th ird Assistant Engineer on the gunboat USS Muscoota until the end of the war. George Westinghouse in the military The gunboat USS Muscoota In August 1865, Westinghouse returned to his family in Schenectady and enrolled at Union College, but dropping out during his first term. He was still only 19 when he invented a rotary steam engine and devised the Westinghouse Farm Engine. At the age of 21, he invented the first of many devices for the railway industry. This was a p iece of equipment (a car replacer ) to guide derailed railway carriages or wag g ons back onto the tracks. -

Park Rankings

PAGE 1 OF 4 Park Scoring Database // Note that the scores in this database are intended to be recalculated each year to factor in new demographic data and changes in park and community conditions. As a result, the Investment Priority Ranking may change. KEY INFORMATION BASIC INFO COMMUNITY NEED SCORES SITE NEED SCORES ENVIRONMENTAL OVERLAY SCORES The final Investment Priority Score is the The final Community Need Score is the sum of the Race & Poverty Score, Youth & Seniors The final Site Need Score is the sum of the Site These scores are not included in the final Investment Priority Score. sum of the Community Need Score and the Score, Neighborhood Condition Score, and Resident Health Score. Condition Score and the Investment Need Score, Below, air quality scores and sewershed priorities were shaded according Site Need Score. The Investment Priority multiplied by two so that it is weighted equal to the to their severity; darker red shading indicates higher scores / priorities. Ranking is assigned to non-passive city final Community Need Score. parks in order of their final score. Capital Investment projects will occur in order of the ranking. INVESTMENT INVESTMENT Site name and section Site split Site category Rec Site's Site acres Walkshed Walkshed RACE & YOUTH & N’HOOD RESIDENT COMMUNITY SITE INVESTMENT SITE NEED BLACK TREE AIR QUALITY SEWERSHED PRIORITY PRIORITY Large sites are split into multiple areas, specified by a description in parentheses into multiple Facility? primary acres qualifies as a POVERTY SENIORS CONDITION HEALTH