Homewood-East-Liberty-Point-Breeze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

61A & 61B-OUT 6-19-05.Qxd

Bus Stops Fares 61B BRADDOCK-SWISSVALE Cash Fares Monday Through Friday Service 61A & 61B Downtown Bus Stops Adult Cash Fares Light Type Shows AM Times From Forbes Avenue at Grant Street To Zone 1 Zone 1A Zone 2 Zone 3 Dark Type Shows PM Times at Smithfield Street Zone 1 1.75 1.75 2.25 2.75 Zone 1A 1.75 1.75 1.75 2.25 To Downtown Pittsburgh To Oakland - Squirrel Hill - Braddock at Wood Street Zone 2 2.25 1.75 1.75 2.25 at Market Street Zone 3 2.75 2.25 2.25 1.75 at Stanwix Street Children (6-11) pay 1/2 the adult cash fare Fifth Avenue at Market Street Children 5 and under (Up to four) ride free when accompanied by a fare-paying passenger. at Wood Street Braddock Oakland Oakland Special Fares Swissvale Swissvale Braddock Squirrel Hill Squirrel Hill Regent Square at Smithfield Street Downtowner Zone Regent Square Craft Avenue Murray Avenue S. Craig Street Stanwix Street Stanwix Street Forbes Avenue at Forbes Avenue at Forbes Avenue at Forbes AvenueMurray atAvenue Forbes Avenue at Forbes AvenueBraddock past Avenue Forbes Avenue past Braddock Avenue Downtown Pittsburgh Forbes Avenue past Adults 1.25 Monongahela Avenue Downtown Pittsburgh Monongahela Avenue at Ross Street 11th St. between Talbot 11th St. between Talbot at Washington Avenue at Washington Avenue and Woodlawn Avenues and Woodlawn Avenues Children (6-11) / People with disabilities .60 5:00 5:11 5:19 5:25 5:30 5:47 5:47 5:58 6:10 6:15 6:21 6:30 Persons with Disabilities Pay Half-fare with a 5:24 5:35 5:43 5:49 5:54 6:11 6:11 6:22 6:34 6:39 6:45 6:54 Medicare ID or state-issued 1/2 fare card except 5:43 5:54 6:02 6:08 6:13 6:30 6:30 6:41 6:53 6:58 7:04 7:13 5:57 6:09 6:20 6:27 6:35 6:55 6:55 7:06 7:18 7:23 7:29 7:38 Schedule Notes on weekdays between 7-8 a.m. -

CITY of PITTSBURGH 2020 Capital Budget & Six Year Plan

CITY OF PITTSBURGH 2020 Capital Budget & Six Year Plan Pittsburgh City Council As approved by City Council December 17, 2019 City of Pittsburgh City Council Members Bruce A. Kraus, President District 3 Darlene M. Harris, Human Resources District 1 Theresa Kail-Smith, Public Works District 2 Anthony Coghill, Urban Recreation District 4 Corey O’Connor, Intergovernmental Affairs District 5 R. Daniel Lavelle, Public Safety District 6 Deborah L. Gross, Land Use & Economic Development District 7 Erika Strassburger, Performance and Asset Management District 8 Rev. Ricky V. Burgess, Finance & Law District 9 City Council Budget Office Bill Urbanic, Budget Director Michael Strelic, Budget Manager Office of the City Clerk Brenda Pree, City Clerk Kimberly Clark-Baskin, Assistant City Clerk Special thanks to Chief Schubert for the cover Additional thanks to Mayor Bill Peduto, City Controller Michael Lamb, the Mayor’s Budget Office staff, and the many citizens who participated through the process Special thanks to Valerie Jacko for design and printing services. Visit us on the web at: www.pittsburghpa.gov 2020 Project Summary 2020 Project Summary Page Project Name 2020 Budget Functional Area: Engineering and Construction 18 28TH STREET BRIDGE (TIP) 250,000 ADVANCED TRANSPORTATION AND CONGESTION MANAGEMENT 20 3,492,571 TECHNOLOGIES DEVELOPMENT (ATCMTD) 22 BRIDGE UPGRADES 4,396,476 24 BUS RAPID TRANSIT - 26 CBD SIGNAL UPGRADES (TIP) - 28 CHARLES ANDERSON BRIDGE (TIP) - 30 COMPLETE STREETS 17,722,742 32 DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION, AND INSPECTION SERVICES 244,011 -

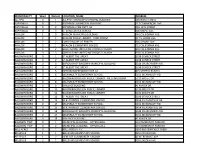

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION NAME ADDRESS

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION_NAME ADDRESS ALEPPO 0 1 ALEPPO TOWNSHIP MUNICIPAL BUILDING 100 NORTH DRIVE ASPINWALL 0 1 ASPINWALL MUNICIPAL BUILDING 217 COMMERCIAL AVE. ASPINWALL 0 2 ASPINWALL FIRE DEPT. #2 201 12TH STREET ASPINWALL 0 3 ST SCHOLASTICA SCHOOL 300 MAPLE AVE. AVALON 1 0 AVALON MUNICIPAL BUILDING 640 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 2 1 AVALON PUBLIC LIBRARY - CONF ROOM 317 S. HOME AVE. AVALON 2 2 LORD'S HOUSE OF PRAYER 336 S HOME AVE AVALON 3 1 AVALON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 721 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 2 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 3 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 1 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 2 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 3 BOROUGH OF BALDWIN MUNICIPAL BUILDING 3344 CHURCHVIEW AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 4 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 5 OPTION INDEPENDENT FIRE CO 825 STREETS RUN RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 6 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 7 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY - MEETING ROOM 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 8 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 9 WALLACE BUILDING 41 MACEK DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 10 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 11 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 12 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 13 W.R. PAYNTER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3454 PLEASANTVUE DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 14 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 15 W.R. -

P1 East Busway-All Stops

P1 EAST BUSWAY ALL STOPS P2 EAST BUSWAY SHORT P1 EAST BUSWAY ALL STOPS MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY SERVICE SATURDAY SERVICE To Downtown Pittsburgh To Wilkinsburg or Swissvale To Downtown Pittsburgh To Wilkinsburg or Swissvale Via Route Via Route Via Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop C East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop C Downtown Penn Station Stop C Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown Smithfield St at Sixth Ave Downtown Penn Station Stop A East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop A Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A Via Route Via Route Via Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Hay St Ramp Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop C East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop C Downtown Penn Station Stop C Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown St Smithfield at Sixth Ave Downtown Penn Station Stop A East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Hay St Ramp Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A P1 4:46 .... 4:52 4:58 5:06 5:08 P1 5:08 5:10 5:14 5:22 5:26 .... 5:31 P1 5:43 5:49 5:54 6:01 6:03 P1 6:03 6:05 6:08 6:15 6:19 6:24 P1 5:06 .... 5:12 5:18 5:26 5:28 P1 5:28 5:30 5:34 5:42 5:46 .... 5:51 P1 6:03 6:09 6:14 6:21 6:23 P1 6:23 6:25 6:28 6:35 6:39 6:44 P1 5:21 ... -

A Menu for Food Justice

A Menu for Food Justice Strategies for Improving Access to Healthy Foods in Allegheny County Zachary Murray Emerson Hunger Fellow 16 Terminal Way Pittsburgh, PA 15219 • telephone: 412.431.8960 • fax: 412.231.8966 • w ww.justharvest.org Table of Contents The Soup- A Light Intro to Food Deserts 4 The Salad- A Food Justice Mix 6 Fishes and Loaves 11 The Main Course: A Taste of the Region 13 Methods 14 Clairton, PA 16 Millvale, PA 19 McKees Rocks and Stowe Township, PA 21 Pittsburgh East End (East Hills, Homewood, Larimer, Lincoln-Lemington- Belmar) 24 Pittsburgh Northside (Fineview, Manchester, Northview Heights, Perry South, Spring Hill, Spring Garden, Troy Hill) 27 Pittsburgh Southside Hilltop (Allentown, Arlington, Arlington Heights, Knoxville, Mt Oliver, St Clair) 33 City of Pittsburgh Sub-Analysis 36 Dessert not Deserts: Opportunities for Healthy Food in Your Community 41 Policy Recommendations 43 A Menu for Food Justice 1 Acknowledgements Just Harvest extends its profound thanks to the Congressional Hunger Center for placing Emerson Hunger Fellow Zachary Murray with Just Harvest for this project during the fall and winter of 2012- 2013. Though a short-term visitor to the Pittsburgh area for this project, Zachary ably led the as- sessment of food desert issues facing our community and is the chief author of this report. The Cen- ter’s assistance to Just Harvest over several years is deeply appreciated. We extend our thanks to the numerous individuals and organizations quoted in this report for their time, interest, and expertise. In addition, we appreciate the generosity of time and spirit showed by many store owners, managers, and employees who welcomed Zach and his team of volunteers as they assessed resources, product mix, and prices at their stores. -

Anatomy of a Neighborhood: Homewood in the 21St Century, 2011

ANATOMY OF A NEIGHBORHOOD: HOMEWOOD IN THE 21ST CENTURY March 2011 Project in support of the Homewood Children’s Village report: State of the Village, 2011 Program in Urban and Regional Analysis University Center for Social and Urban Research University of Pittsburgh 121 University Place Pittsburgh, PA 15260 Homewood Children’s Village University of Pittsburgh School of Social Work Center on Race and Social Problems Executive Summary The Urban and Regional Analysis program at the University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) has been engaged in a number of projects involving Pittsburgh neighborhoods, with its Pittsburgh Neighborhood and Community Information System (PNCIS) serving as a valuable resource for these projects. Homewood is a neighborhood in Pittsburgh’s East End that has experienced tremendous change since the 1940s, as suburbanization, population loss and post-industrial restructuring of the Pittsburgh region have deeply affected this community. This report summarizes collaboration between UCSUR and the Homewood Children’s Village in 2010. Information from this study will also be part of the Homewood Children’s Village State of the Village (2011).1 Some prominent changes and trends analyzed in this report include: Homewood continues to lose population. Between 2000 and 2010, Homewood’s population dropped 30.6 percent, to 6,600 residents. In Homewood South and Homewood West, residents aged 65 and over make up nearly a third of the population. The average sales price for existing residential homes in Homewood was $9,060 in 2009, one-tenth the average price for a home in the City of Pittsburgh. This 2009 price represents a substantial loss of home equity from twenty years earlier, when the average home sold for over $22,000 in current (2010) dollars. -

PARISHES in UNION with and PARTICIPATING in the EPISCOPAL DIOCESE of PITTSBURGH As of August 31, 2020

PARISHES IN UNION WITH AND PARTICIPATING IN THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF PITTSBURGH as of August 31, 2020 BLAIRSVILLE (1828) CRAFTON (1872) St. Peter’s Episcopal Church Church of the Nativity 36 W. Campbell St., Blairsville, PA 15717 33 Alice St., Pittsburgh, PA 15205 724-459-8804 412-921-4103 The Rev. Joseph Baird, Vicar The Rev. Shawn Malarkey, Rector BRACKENRIDGE (1884) DONORA (1924) St. Barnabas Episcopal Church St. John’s Episcopal Church 989 Morgan St., Brackenridge, PA 15014 998 Thompson Ave., Donora, PA 15033 724-224-9280 412-969-6427 The Rev. Frank Yesko, Priest-in-Charge EAST LIBERTY (1855) BRENTWOOD (1939) Calvary Episcopal Church St. Peter’s Episcopal Church 315 Shady Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15206 4048 Brownsville Rd., Pittsburgh, PA 15227 412-661-0120 412-884-5225 The Rev. Jonathon W. Jensen, Rector The Rev. Canon Dr. Wm. Jay Geisler, Rector The Rev. Leslie Reimer, Sr. Associate Rector The Rev. Neil Raman, Associate Rector BRIGHTON HEIGHTS (1889) The Rev. Carol Henley, Assisting Priest All Saints Episcopal Church The Rev. Geoffrey S. Royce, Deacon 3577 McClure Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15212 The Rev. Ruth Bosch Becker (ELCA) Assisting 412-766-8112 Pastor The Rev. Dr. Bruce Robison, Vicar The Rev. BROOKLINE (1904) FRANKLIN PARK (1987) Church of the Advent St. Brendan’s Episcopal Church 3010 Pioneer Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15226 2365 McAleer Rd., Sewickley, PA 15143 412-561-4520 412-364-5974 The Rev. Regis Smolko, Priest-in-Charge CANONSBURG (1866) The Rev. Dr. Julie Smith, Youth Ministries St. Thomas Episcopal Church Coordinator 139 N. Jefferson Ave., Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-2013 HAZELWOOD (1870) The Rev. -

Affordable Housing Plan for Fineview & Perry Hilltop

A FIVE-YEAR AFFORDABLE HOUSING PLAN FOR FINEVIEW & PERRY HILLTOP PERRY W H IE IL V L E T O N I P P F P O E T R L R L I www . our future hilltop . org Y H H Y I L R L R T E O P PE P R R Y F W I E I N V W E H PREPARED BY: IE IL V L E T Studio for Spatial Practice O N I P P F Valentina Vavasis Consulting P O E T R L R L I Ariam Ford Consulting www . our future hilltop . org Y H H Y I L R L R T E O P P PER R F W I E I N Y V W E H IE IL V L E T O N I P P F P O E T R L R L I www . our future hilltop . org Y H H Y I L R L R T E O P P F W I E I N V E FIVE-YEAR AFFORDABLE HOUSING PLAN ACKNOWLEDGMENTS PREPARED BY Special Thanks to: Studio for Spatial Practice Valentina Vavasis Consulting Fineview Citizens Council Housing Working Group Board Of Directors Members Ariam Ford Consulting Christine Whispell, President Fred Smith, Co-Chair Terra Ferderber, Vice President Sally Stadelman, Co-Chair FOR Jeremy Tischuk, Treasurer Robin Alexander, former Chair Fineview Citizens Council Greg Manley, Secretary Betty Davis Perry Hilltop Citizens Council Chris Caldwell Diondre Johnson Diondre Johnson Lance McFadden WITH SUPPORT FROM Robyn Pisor Doyle Mel McWilliams The Buhl Foundation Cheryl Gainey Eliska Tischuk ONE Northside Tiffany Simpson Christine Whispell Eliska Tischuk Lenita Wiley Perry Hilltop Citizens Council Fineview and Perry Hilltop Board Of Directors Citizens Council Staff Dwayne Barker, President Joanna Deming, Executive Director Reggie Good, Vice President Lukas Bagshaw, Community Gwen Marcus, Treasurer Outreach Coordinator Janet Gunter, Secretary Carla Arnold, AmeriCorps VISTA Engagement Specialist Pauline Criswell Betty Davis Gia Haley Lance McFadden Sally Stadelman Antjuan Washinghton Rev. -

Allegheny County Community Learning Hubs Safe Places for Kids to Go to Do Schoolwork and Participate in Enrichment Activities During COVID-19

Allegheny County Community Learning Hubs Safe places for kids to go to do schoolwork and participate in enrichment activities during COVID-19. Why a learning hub? • Children will be grouped in pods of 10 or fewer and will spend the entire day Learning hubs are a great option for parents who need childcare when in-person with that pod school is not in session. Learning hub staff will help facilitate the virtual curriculum • Adequate spaces, desk and chairs are available to maintain physical distancing from your child’s school district in the morning and conduct fun activities with them in the afternoon. • Children must wear their own mask at all times, except when eating or drinking Locations What is a day like at a learning hub? There are more than 50 learning hubs in Allegheny County. Most locations are Most learning hubs are open all day on weekdays (check with the hub you are open Monday through Friday during normal school hours. Contact a hub near you interested in for exact times). Free Wi-Fi is available, but your child should bring to enroll and to find out more. their own technology device (laptop computer, tablet, phone). Each child will get headphones for online work. Eligibility Every learning hub has free spots available for low-income families, with priority Staff will help children in the following ways: for families experiencing homelessness, families involved in child welfare or other • Help children get online each morning and keep them motivated to engage human services and children of essential workers. Some learning hub locations virtually offer flexibility with payment including private pay, subsidies and free options. -

City of Pittsburgh Neighborhood Profiles Census 2010 Summary File 1 (Sf1) Data

CITY OF PITTSBURGH NEIGHBORHOOD PROFILES CENSUS 2010 SUMMARY FILE 1 (SF1) DATA PROGRAM IN URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND URBAN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH JULY 2011 www.ucsur.pitt.edu About the University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) The University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) was established in 1972 to serve as a resource for researchers and educators interested in the basic and applied social and behavioral sciences. As a hub for interdisciplinary research and collaboration, UCSUR promotes a research agenda focused on the social, economic and health issues most relevant to our society. UCSUR maintains a permanent research infrastructure available to faculty and the community with the capacity to: (1) conduct all types of survey research, including complex web surveys; (2) carry out regional econometric modeling; (3) analyze qualitative data using state‐of‐the‐art computer methods, including web‐based studies; (4) obtain, format, and analyze spatial data; (5) acquire, manage, and analyze large secondary and administrative data sets including Census data; and (6) design and carry out descriptive, evaluation, and intervention studies. UCSUR plays a critical role in the development of new research projects through consultation with faculty investigators. The long‐term goals of UCSUR fall into three broad domains: (1) provide state‐of‐the‐art research and support services for investigators interested in interdisciplinary research in the behavioral, social, and clinical sciences; (2) develop nationally recognized research programs within the Center in a few selected areas; and (3) support the teaching mission of the University through graduate student, post‐ doctoral, and junior faculty mentoring, teaching courses on research methods in the social sciences, and providing research internships to undergraduate and graduate students. -

Historical Society Notes and Documents Homewood At

HISTORICAL SOCIETY NOTES AND DOCUMENTS HOMEWOOD AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY Donald C. Scully follows is a personal recollection about that part of Pitts- Whatburgh's East End known as Homewood at the turn of the century. Iam jotting this down because Ifeel an attempt should be made to do so before things worth remembering are forgotten. While doing this Ihave tried to be exact, as one who records the past must be very careful not to exaggerate or distort the facts. At that time other cities had their North Sides, South Sides, West Sides, and East Sides. Pittsburgh's East End was among the finest. Concentrated inthe Homewood area alone were many mansions and considerable wealth. It is a pity someone blessed with literary ability has not researched carefully this historical section for here lived pioneers in steel, oil, coal and coke, pickles, cork, electrical energy, natural gas, railway safety devices, retail and wholesale mer- chandising, and banking. In the comparatively short distance from Beechwood Boulevard and Fifth Avenue to Braddock and Penn avenues, and a few blocks either way, there were more than a score of large estates, most of them surrounded by stone or brick walls, sedate iron gates, or a com- bination—of the three, each one —with a stable filled with carriages and horses maybe a pony or two luxurious gardener-kept lawns, and accompanying flower and vegetable gardens. Many had the large greenhouses which were in vogue before the craze for swimming pools. Some had their chosen names carved in the gateposts :"Beech- wood Hall," Frew; "Pennham," Jackson; "Clayton," Frick; and the Heinz estate, "Greenlawn." Today these estates are either subdivisions or parks. -

Homewood Cluster Planning: Final Consensus Vision Plans November 2015 Table of Contents

7 6 2 5 Business and Institutional Core 8 9 4 1 3 Homewood Cluster Planning: Final Consensus Vision Plans November 2015 Table of Contents Cluster Planning Overview 3 OPERATION BETTER BLOCK, INC. Cluster Planning Process 4 Reweaving The Fabric of Community Life Community Development Principles 6 Community Development Initiatives Overview 8 First, I would like to thank the residents and business owners of Homewood for their participation in this planning process. We have made history together by Neighborhood Existing Conditions engaging 80% of the community in the planning process!!! Second, this effort would not have been possible without the funding support of the R. K. Mellon Existing Conditions 10 Foundation. Third, I would like to thank Studio for Spatial Practice for their Existing Vacancy 12 willingness to try something new! Last and certainly not least, I would like to give a huge thank you and big congratulations to Operation Better Block staff Public Ownership 13 for their hard work and dedication to the process and the organization. Existing Uses 14 This is a very exciting time for Homewood!! Having a land use plan that is resident driven creates endless possibilities for the community. Using data and Existing Zoning 15 a door-to-door engagement strategy has allowed us to create an urban planning process that can be duplicated across our region. It is the possibilities Land Use Category Matrix 16 of what Homewood can be in the very near future that keeps me up at night!! Neighborhood Final Plan The real work has not begun. Now that we have a land use plan, let’s get busy Consensus Vision Plans 18 creating the Homewood you want to live in, work in, and relax in!! Zoning Change Recommendations 20 This is what I truly believe: Open Space Recommendations 24 “There Is No Development That Is For Us, That Is Not Led By Us.” Business & Institutional Core Recommendations 28 Love & Respect Housing Recommendations 36 Next Steps 40 Available Resources 41 Jerome M.