A Menu for Food Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Y of Pitt Tsburgh H, Alleg Gheny C County Y, Penn Sylvani Ia

Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania Planning Sector 1: Troy Hill Report of Findings and Recommendations The City of Pittsburgh In Cooperation With: Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission October 2014 The Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, was made possible with funding provided by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), the City of Pittsburgh, and the U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Certified Local Government program. The contents and opinions contained in this document do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. This program receives federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service; 1849 C Street N.W.; Washington, D.C. 20240. 2 | Page abstract Abstract This architectural inventory for the City of Pittsburgh (Planning Sector 1: Troy Hill) is in partial fulfillment of Preserve Policy 1.2, to Identify and Designate Additional Historic Structures, Districts, Sites, and Objects (City of Pittsburgh Cultural Heritage Plan, 2012). This project is the first phase of a larger undertaking which aims to ultimately complete the architectural survey for all of Pittsburgh’s Planning Sectors. -

PUBLICLY SPEAKING Winter 2020 a MESSAGE from the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

News& Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh PUBLICLY SPEAKING Winter 2020 A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR The Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh (HACP) is set to roar its way into the 20s. The HACP is engaged in long-term community revitalization plans in the East End, North Side, IN THIS ISSUE and elsewhere throughout the city. We will double down on our commitment to improving and expanding affordable housing Cornerstone Village Opens As HACP, Larimer options for those in search of a place to call home and we will Community, and Development Partners continue to ensure that self-sufficiency programs are accessible to any HACP resident seeking to improve their quality of life. Celebrate Larimer Choice Progress ........ 2 As we move into the new decade, we look forward to making HACP Celebrates 21 Years of Clean Slate more progress on our developments throughout the city. Having Youth Programming At Benefit Dinner .... 4 completed new phases of Cornerstone Village and Sandstone Quarry in 2019, we have set on advancing new housing developments in Homewood, 412 Food Rescue and HACP Bring the Hill District and Northview Heights. Our upcoming development activities aren’t Baby Food to Northview Heights and limited to new communities: we are committed to maintaining modern facilities for Allegheny Dwellings ............................... 5 our residents, which is why we will be modernizing several housing communities and community assets such as the Bedford Hope Center. Lyft Expands Access to Fresh Food for Bedford Dwellings Residents............. 6 Looking back, we are very proud of what we accomplished in the second half of 2019. -

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin-submitted November 5, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I Fieldwork Methodology 3 II Prior Research Resources 5 III Allegheny Town in General 5 A. Prologue: "Allegheny is a Delaware Indian word meaning Fair Water" B. Geography 1. Neighborhood Boundaries: Past and Present C. Settlement Patterns: Industrial and Cultural History D. The Present E. Religion F. Co mmunity Centers IV Troy Hill 10 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. The Fichters 2. Czech/Bohemian D. Community Celebrations V Spring Garden/The Flats 14 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity VI Spring Hill/City View 16 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German D. Community Celebrations VII East Allegheny 18 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. Churches b. Teutonia Maennerchor 2. African Americans D. Community Celebrations E. Church Consolidation VIII North Shore 24 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Heinz House D. Ethnicity 1. Swiss-German 2. Croatian a. St. Nicholas Croatian Roman Catholic Church b. Javor and the Croatian Fraternals 3. Polish IX Allegheny Center 31 2 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Farmers' Market D. Ethnicity 1. Greek a. Grecian Festival/Holy Trinity Church b. Gus and Yia Yia's X Central Northside/Mexican War Streets 35 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. African Americans: Wilson's Bar BQ D. Community Celebrations XI Allegheny West 36 A. -

61A & 61B-OUT 6-19-05.Qxd

Bus Stops Fares 61B BRADDOCK-SWISSVALE Cash Fares Monday Through Friday Service 61A & 61B Downtown Bus Stops Adult Cash Fares Light Type Shows AM Times From Forbes Avenue at Grant Street To Zone 1 Zone 1A Zone 2 Zone 3 Dark Type Shows PM Times at Smithfield Street Zone 1 1.75 1.75 2.25 2.75 Zone 1A 1.75 1.75 1.75 2.25 To Downtown Pittsburgh To Oakland - Squirrel Hill - Braddock at Wood Street Zone 2 2.25 1.75 1.75 2.25 at Market Street Zone 3 2.75 2.25 2.25 1.75 at Stanwix Street Children (6-11) pay 1/2 the adult cash fare Fifth Avenue at Market Street Children 5 and under (Up to four) ride free when accompanied by a fare-paying passenger. at Wood Street Braddock Oakland Oakland Special Fares Swissvale Swissvale Braddock Squirrel Hill Squirrel Hill Regent Square at Smithfield Street Downtowner Zone Regent Square Craft Avenue Murray Avenue S. Craig Street Stanwix Street Stanwix Street Forbes Avenue at Forbes Avenue at Forbes Avenue at Forbes AvenueMurray atAvenue Forbes Avenue at Forbes AvenueBraddock past Avenue Forbes Avenue past Braddock Avenue Downtown Pittsburgh Forbes Avenue past Adults 1.25 Monongahela Avenue Downtown Pittsburgh Monongahela Avenue at Ross Street 11th St. between Talbot 11th St. between Talbot at Washington Avenue at Washington Avenue and Woodlawn Avenues and Woodlawn Avenues Children (6-11) / People with disabilities .60 5:00 5:11 5:19 5:25 5:30 5:47 5:47 5:58 6:10 6:15 6:21 6:30 Persons with Disabilities Pay Half-fare with a 5:24 5:35 5:43 5:49 5:54 6:11 6:11 6:22 6:34 6:39 6:45 6:54 Medicare ID or state-issued 1/2 fare card except 5:43 5:54 6:02 6:08 6:13 6:30 6:30 6:41 6:53 6:58 7:04 7:13 5:57 6:09 6:20 6:27 6:35 6:55 6:55 7:06 7:18 7:23 7:29 7:38 Schedule Notes on weekdays between 7-8 a.m. -

Review of Community Assets and Priorities

Review of Community Assets and Priorities Prepared for Duquesne University’s Center for Community-Engaged Teaching and Research Strategic Planning Process January 13, 2017 Prepared by Megan Good and Jamillia Kamara Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 7 Methods 8 Background 9 Current Community Priorities and Assets 12 Common Themes 12 Community Development 13 Culture and Civic Engagement 19 Education and Skill Development 20 Health and Wellness 23 Housing 27 Public Safety 31 Transportation 33 Community Snapshots 36 Hazelwood 36 Hill District 38 Hilltop 40 Uptown 41 Sources 43 2 Acknowledgements We would like to extend our gratitude to all the community residents, leaders, stakeholders, and Duquesne University staff and faculty who shared their time, energy, stories, and insights with us. We value how generous you were with your time, connections, and honesty as we sought to better understand the rich and complex neighborhood dynamics and histories. The information we learned directly from community stakeholders provided valuable context for the community plans we reviewed, and we could not have pulled together such a comprehensive review without everyone’s support. Thank you! 3 Executive Summary Figure 1. Focus Communities Commissioned by the Center for Community-Engaged Teaching and Research (CETR) at Duquesne University, this report serves as one input to CETR’s 2016-2017 strategic planning process. As a Spiritan institution, Duquesne University is committed to a practice of community engagement which prioritizes developing authentic relationships, walking with those who have been marginalized, and being open to new perspectives and approaches. As a result, it is important for community priorities to be centered in the strategic plan. -

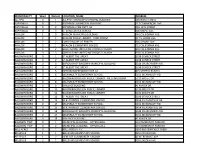

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION NAME ADDRESS

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION_NAME ADDRESS ALEPPO 0 1 ALEPPO TOWNSHIP MUNICIPAL BUILDING 100 NORTH DRIVE ASPINWALL 0 1 ASPINWALL MUNICIPAL BUILDING 217 COMMERCIAL AVE. ASPINWALL 0 2 ASPINWALL FIRE DEPT. #2 201 12TH STREET ASPINWALL 0 3 ST SCHOLASTICA SCHOOL 300 MAPLE AVE. AVALON 1 0 AVALON MUNICIPAL BUILDING 640 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 2 1 AVALON PUBLIC LIBRARY - CONF ROOM 317 S. HOME AVE. AVALON 2 2 LORD'S HOUSE OF PRAYER 336 S HOME AVE AVALON 3 1 AVALON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 721 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 2 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 3 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 1 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 2 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 3 BOROUGH OF BALDWIN MUNICIPAL BUILDING 3344 CHURCHVIEW AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 4 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 5 OPTION INDEPENDENT FIRE CO 825 STREETS RUN RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 6 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 7 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY - MEETING ROOM 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 8 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 9 WALLACE BUILDING 41 MACEK DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 10 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 11 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 12 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 13 W.R. PAYNTER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3454 PLEASANTVUE DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 14 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 15 W.R. -

P1 East Busway-All Stops

P1 EAST BUSWAY ALL STOPS P2 EAST BUSWAY SHORT P1 EAST BUSWAY ALL STOPS MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY SERVICE SATURDAY SERVICE To Downtown Pittsburgh To Wilkinsburg or Swissvale To Downtown Pittsburgh To Wilkinsburg or Swissvale Via Route Via Route Via Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop C East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop C Downtown Penn Station Stop C Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown Smithfield St at Sixth Ave Downtown Penn Station Stop A East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop A Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A Via Route Via Route Via Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Hay St Ramp Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop C East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop C Downtown Penn Station Stop C Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown Liberty Ave at 10th St Downtown St Smithfield at Sixth Ave Downtown Penn Station Stop A East Liberty East Liberty Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Wilkinsburg Station Stop A Wilkinsburg Hay St Ramp Swissvale Swissvale Station Stop A P1 4:46 .... 4:52 4:58 5:06 5:08 P1 5:08 5:10 5:14 5:22 5:26 .... 5:31 P1 5:43 5:49 5:54 6:01 6:03 P1 6:03 6:05 6:08 6:15 6:19 6:24 P1 5:06 .... 5:12 5:18 5:26 5:28 P1 5:28 5:30 5:34 5:42 5:46 .... 5:51 P1 6:03 6:09 6:14 6:21 6:23 P1 6:23 6:25 6:28 6:35 6:39 6:44 P1 5:21 ... -

64 Lawrenceville-Waterfront

64 LAWRENCEVILLE-WATERFRONT MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY SERVICE To Bloomfield - Lawrenceville To Squirrel Hill - Waterfront Waterfront Giant Eagle Waterfront Dr Waterfront Drvwy Costco at Greenfield Murray Ave past Hazelwood Ave Squirrel Hill Murray Ave at Forbes Ave Squirrel Hill Forbes Ave at Shady Ave Shadyside Fifth Ave at S Highland Ave Shadyside S Negley Ave at East Busway Steps Friendship Park Friendship Ave at S Millvale Ave Children's Hospital Penn Ave at 44th St Lawrenceville 39th St at Butler St Lawrenceville 39th St at Butler St Children's Hospital Penn Ave opp. 44th St Friendship Park Friendship Ave Hospital Penn West at Shadyside Centre Ave at S Negley Ave Shadyside Fifth Ave opp. S Highland Ave Squirrel Hill Shady Ave at Forbes Ave Squirrel Hill Murray Ave at Darlington Rd Greenfield Murray Ave at Hazelwood Ave West Homestead Dr Waterfront opp. Costco driveway Waterfront Giant Eagle Waterfront Lowe's Home Center 5:24 5:27 5:34 5:40 5:41 5:45 5:49 5:54 5:57 6:00 5:35 5:39 5:41 5:46 5:50 5:55 5:56 6:03 6:07 6:12 6:14 6:09 6:12 6:21 6:28 6:30 6:35 6:39 6:45 6:48 6:51 6:05 6:09 6:11 6:16 6:20 6:25 6:26 6:33 6:37 6:42 6:44 6:39 6:42 6:51 6:58 7:00 7:05 7:09 7:15 7:18 7:21 6:35 6:39 6:41 6:46 6:50 6:55 6:56 7:03 7:07 7:12 7:14 7:14 7:17 7:26 7:36 7:38 7:43 7:47 7:54 7:57 8:00 7:05 7:09 7:12 7:19 7:23 7:29 7:32 7:39 7:43 7:48 7:50 7:44 7:47 7:56 8:06 8:08 8:13 8:17 8:24 8:27 8:30 7:35 7:39 7:42 7:49 7:53 7:59 8:02 8:09 8:13 8:18 8:20 8:14 8:17 8:26 8:36 8:38 8:43 8:47 8:54 8:57 9:00 8:05 8:09 8:12 8:19 8:23 8:29 8:32 8:39 8:43 8:48 -

The Hazelwood Neighborhood, 2010

The Hazelwood Neighborhood, 2010 Photo Credit: RIDC PROGRAM IN URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND URBAN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FEBRUARY 2012 www.ucsur.pitt.edu Executive Summary Hazelwood is a City of Pittsburgh neighborhood of 5,033 residents (2010 Census) located along the northern shore of the Monongahela River, approximately four miles from Downtown Pittsburgh. The neighborhood developed over 100 years ago, shaped by several steel and coke-making plants located in and around the community. In recent decades, Hazelwood has lost its manufacturing base, experienced population decline, physical abandonment, and weak demand for housing. This report presents information on the current condition of the Hazelwood community across a broad range of indicators. In this report, data for Hazelwood includes the combined totals for both the Hazelwood and Glen Hazel neighborhoods as defined by the City of Pittsburgh. Hazelwood had disproportionately smaller shares of young adults (ages 20-34), when compared to the City of Pittsburgh. While the combined population was majority-white, the community had a larger share of African American population when compared to Pittsburgh. Nearly one in three households in the two neighborhoods contained a person under age 18 compared to 1 in 5 in the City, and the majority of these households were female-headed, with no husband present. Compared to the City of Pittsburgh, households in Hazelwood had lower incomes, and residents (especially children) were more- likely to be poor. A number of indicators included in this report strongly suggest Hazelwood’s housing market suffers from a lack of demand. Prices are extremely low (sales under $10,000 are common), the pace of sales trails the City, and low levels of mortgage originations and falling homeownership rates suggest that much of the market activity is being driven by investors through cash transactions. -

Larimer East Liberty Shadyside Highland Park

I Cit y of Pittsburgh - Depa rtment of C it y Planning - Geogra phic Informa tion Sy stems - C ity of Pittsburgh - Depa rtment of C ity Pla nning - Geogra phic Informat ion Sy stems - City of Pittsbur gh - D epar tment of City Pla nning - Geographic Information Sy stems - City of Pit tsburgh - D epar tment of City Pla nning - G eogr aphic Information Sys tems - City of Pitt sburgh - Depart ment of City Planning - G eogr aphic Infor ma tion Syst ems - City of Pitts burgh - Depa rtment of City Planning - Geogra phic Infor ma tion Systems - Cit y of Pittsburgh - Depa rtment of Cit y Planning - Geogra phic Informa tion Sy stems - C ity of Pittsburgh - Depa rtment of C ity Pla nning - Geogra phic Informa tion Sy stems - City of Pittsbur gh - D epar tment of City Pla nning - Geographic Information Sy stems - City of Pit tsburgh - D epar tment of City Pla nning - G eogr aphic Information Sys tems - City of Pitt sburgh - Depart ment of City Planning - G eogr aphic Infor ma tion Syst ems - City of Pitts burgh - Depa rtment of City Planning - Geogra phic Infor ma tion Systems - Cit y of Pittsburgh - Depa rtment of Cit y Planning - Geogra phic Informa tion Sy stems - C ity of Pittsburgh - Depa rtment of C ity Pla nning - Geogra phic Informa tion Sy stems - City of Pittsbur gh - D epar tment of City Pla nning - Geographic Informat ion Sy stems - City of Pit tsbur gh - D epar tment of City Pla nning - G eogr aphic Information Sys tems - City of Pitt sburgh - Depart ment of City Planning - G eogr aphic Infor mation Syst ems - City of Pitts burgh - -

Regular Board Meeting November 8, 2018 Urban

REGULAR BOARD MEETING NOVEMBER 8, 2018 URBAN REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY OF PITTSBURGH AGENDA “A” 1. General a. Approval of the Minutes of the Regular Board Meeting of October 8, 2018. 2. Announcements a. RFP’s, RFQ’s and Bids i. Requests for proposals (RFP) for the Rental Gap Program has been released. Submittals will be received on a rolling basis. ii. Request For proposals (RFP) for Landscape Operations & Maintenance services for the East Liberty Transit Center, on behalf of the East Liberty Transit Revitalization Investment District Authority. b. TWG (South Side Works) MWBE Outreach Event: November 14, 2018, at CoLab18, Nova Place, former Allegheny Center Mall from 6 PM to 8 PM. c. Hill District Community Meeting: November 29, 2018, from 6:00 PM to 7:30 PM at the Thelma Lovette YMCA. d. URA‐funded Catapult Program grand opening for Gallery on Penn was held on November 2, 2018 at 5935 Penn Avenue e. The URA will provide up to four scholarships for Pittsburgh neighborhood business district staff and volunteers to attend the National Mainstreets Conference located in Seattle, Washington in March 2019. 3. Hazelwood – Woods House 1 a. Final drawings, final evidence of financing, and authorization to execute a deed for the sale of Block 55‐P, Lots 37 and 39, in the 15th Ward to Woods House LLC, for $25,000.00. 4. Housing a. Northside Residences Phase II 1. Final Authorization to Issue Multifamily Financing Bonds in the amount up to $26.0 million 2. Rental Housing Development and Improvement Program (RHDIP) Loan Agreement in the amount of up to $1,100,000.00 with the Northside Properties Residences II LLC b. -

Food Bank/WIC Food Bucks Flier with Locations

WIC failies ca get extra fruits ad veggies wit Food Bucks! Food Bucks are $2 coupos tat ca be used to buy ANY fres fruits or vegetables at participatig locatios. (Produce does ot ave to be grow i PA) Sca te QR code, or visit tefoodtrust.org/foodbucks/westerPA for te ost up to date site list. Site details listed o back are subject to cage. Questions? Contact The Food Trust: Text or call 412-357-2221 Email [email protected] May arkets accept Food Bucks AND WIC FMNP Cecks. Dowload te FMNP MARKET LOCATOR app to fid your closest participatig arket. Available o te App Store ad Google Play. Suer Soppig Guide: Redeem Food Bucks at a market near you! Farmers Markets & Stands (also accept WIC FMNP checks) Bellevue Wed., 3-7 p.m. (Jun. 2-Oct. 27), Bayne Park, 34 N. Balph Ave. Bloomfield Sat., 9 a.m.-1 p.m. (May 8-Nov. 20), 5050 Liberty Ave. Braddock Sat., 9 a.m.-1 p.m. (Apr. 24-Nov. 27), 10th St. & Braddock Ave. Wed., 3:30-6 p.m. (Jun. 2-Nov. 24), 10th St & Braddock Ave. Carnegie Sun., noon-3 p.m. (Jul. 11- Sep. 26), E. Main St. between Broadway/Mary Carrick Wed., 3-7 p.m. (May 12-Nov. 24), Carrick Dairy District, 1529 Brownsville Road Downtown Thu., 10 a.m.-2 p.m. (May 13-Oct. 23), Market Square East Liberty Mon., 3-7 p.m. (May 10-Nov. 22), Garland Parklet on N. Euclid Ave. East Liberty Sat., 5 a.m.-noon (year-round), 344 Sheridan Ave.