The Empty Noun Construction in Persian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semiotic Analysis of Form and Meaning in Vakil Mosque of Shiraz

Journal of Research Islamic Art Studies, Volume 14, Issue 29, Spring 2018 Semiotic Analysis of Form and Meaning in Vakil Mosque of Shiraz Laripour, Negin*1 Dadvar, Abolghasem2 Abstract Symbolism is one of the old principles of human thought that has been shown in the works of art since the beginning of its periods of life, and according to Islamic views, the symbol is the apparent and secular aspect of spiritual nature. The religious artist in the expression of concepts and the giving of material means to them is the use of the language of allegory. Among the positions of the appearance of symbols in Iranian art is architecture. Considering the meaningful capabilities of the mosque architecture, using the semiotic method, we will analyze the symbolic concepts and spiritual meanings of these artistic works. The elements that are considered as symbols are considered to be functional and have become symbolic over time. The method of research is descriptive-historical, with a semiotic approach based on the theory of "Charles Saunders Pierce" to examine his pattern in the secondary implications of decorative motifs and the architecture of the mosque in the Vakil mosque of Shiraz, as part of a semiotic study and try to It is to examine the decorative elements and physical elements of the mosque and the effect they have on translating their meanings and concepts. At first, using the method of shooting and observing the amount and type of signs used and in the next section, we will analyze and review each of their images and symbols in the architecture of the mosque attorney. -

(2016), Volume 4, Issue 6, 1576-1591

ISSN 2320-5407 International Journal of Advanced Research (2016), Volume 4, Issue 6, 1576-1591 Journal homepage: http://www.journalijar.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Journal DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01 OF ADVANCED RESEARCH RESEARCH ARTICLE THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE ACADEMY POLY WORDS, NUMBER 2 (PHYSICS 1 BEGINNING HALF). Mahdieh Farazfar. A graduate student in general linguistics. Manuscript Info Abstract Manuscript History: This paper is a library study which pays to evaluate, constructing the word in Farsi language in physics one thousand words book, in the case of the Received: 16 April 2016 Final Accepted: 26 May 2016 derivative, compound, derivative - compound, and extensiveness in Persian Published Online: June 2016 language. It also has been given to the incidence rate of application, in terms of construction Academy words, and Persian Language and Literature. Key words: Considered view in this study is "structuralism", and the method of the study grammar, word, morpheme, free Analytical - descriptive. In this paper the researchers sought to answer this morpheme, bound morpheme, affix, question that, in the word-building in the Academy, which types of inflectional affix, derivational affix, morphology is mostly used and which one is less used? The Academy word- prefix, infix, suffix. building, which affixes (prefix or suffix) have the most used and which is *Corresponding Author used less? Which present or past infinitive has mostly used, and which is used less? Which is the source of most applications? Which preposition Mahdieh Farazfar. usage is more or less used? Which Western prefix (prefix or suffix) are used more or less? Which Western word is more or less used? Which Western verbs (present or past) are more or less used? The results show that, it seems that in the word-building in the Academy, words (derivatives) are mostly used, and derivative – compound words are used less frequently. -

Le Cours De Linguistique Générale: Réception, Diffusion, Traduction

Le Cours de linguistique générale: réception, diffusion, traduction édité par John JOSEPH et Ekaterina VELMEZOVA ! ! ! ! ! Juhul, kui sõnade ülesandeks oleks representeerida etteantud mõisteid, oleks ühe keele igal sõnal tähenduse poolest täpne vaste teises keeles; ometi pole see nõnda.! ! If words stood for ! Se as palavras estivessem ! pre-existing ! encarregadas de representar os concepts, they would conceitos dados de antemão, all have exact cada uma delas teria, de uma equivalents in língua para outra, meaning from one correspondentes exatos para o language to the next; sentido; mas não ocorre assim.! but this is not true.! ! Wenn die Wörter die ! Aufgabe hätten, vorgegebene Konzepte Hitzek aldez aurretik emanak wiederzugeben, hätte jedes leudekeen kontzeptuak von einer Sprache zur adierazi behar andern ganz genaue balituzte, kontzeptu horietako bakoitzak Sinnentsprechungen ; dem bere ordaina izango ist aber nicht so.! luke hizkuntza guztietan ; baina ez da hala gertatzen.! ! Si les mots étaient chargés ! Se as palavras de représenter des ! tivessem a função de concepts donnés d'avance, ! representar ils auraient chacun, d'une ! conceitos langue à l'autre, des ! prèviamente correspondants exacts Wenn die Wörter die Aufgabe determinados, todas pour le sens; or il n'en est hätten, von vornherein elas teriam, em cada pas ainsi. gegebene Vorstellungen língua, darzustellen, hätte jedes correspondentes hinsichtlich seines Sinnes in exactos quanto ao einer Sprache wie in allen Если бы слова sentido; ora não é andern ganz genaue служили для assim. Entsprechungen; das ist aber выражения заранее nicht der Fall.! данных понятий, то каждое из них находило бы точные смысловые соответствия в любом языке; но в действительности это не так.! ! ! ! Cahiers de l’ILSL, № 57, 2018 ! Cahiers de l’ILSL, № 57, 2018, pp. -

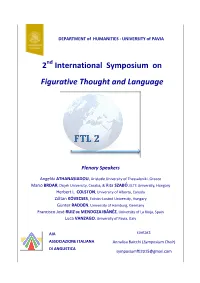

2 International Symposium on Figurative Thought and Language

DEPARTMENT of HUMANITIES - UNIVERSITY of PAVIA 2nd International Symposium on Figurative Thought and Language Plenary Speakers Angeliki ATHANASIADOU, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece Mario BRDAR, Osijek University, Croatia, & Rita SZABÓ, ELTE University, Hungary Herbert L. COLSTON, University of Alberta, Canada Zóltan KÖVECSES, Eötvös-Loránd University, Hungary Günter RADDEN, University of Hamburg, Germany Francisco José RUIZ DE MENDOZA IBÁNÉZ, University of La Rioja, Spain Luca VANZAGO, University of Pavia, Italy AIA contact: ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA Annalisa Baicchi (Symposium Chair) DI ANGLISTICA [email protected] BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Table of contents Senior Consultant Committee Scientific Committee Symposium Chair Organizing Committee Abstracts 2 Senior Consultant Committee Angeliki ATHANASIADOU (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) Annalisa BAICCHI (University of Pavia, Italy) Mario BRDAR (Osijek University, Croatia) Herbert COLSTON (University of Alberta, Canada) Ad FOOLEN (Rabdoub University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Klaus-Uwe PANTHER (University of Hamburg, Germany) Günter RADDEN (University of Hamburg, Germany) Francisco RUIZ DE MENDOZA (University of La Rioja, Spain) Gerard STEEN (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Scientific Committee Stefano ARDUINI (Urbino); Angeliki ATHANASIADOU (Thessaloniki); Annalisa BAICCHI (Pavia); Valentina BAMBINI (IUSS, Pavia); Antonio BARCELONA (Cordoba); Carla BAZZANELLA (Torino); Marcella BERTUCCELLI PAPI (Pisa); Réka BENCZEK (Budapest); Boguslaw BIERWIACZONEK -

950-953 Issn 2322-5149 ©2014 Jnas

Journal of Novel Applied Sciences Available online at www.jnasci.org ©2014 JNAS Journal-2014-3-9/950-953 ISSN 2322-5149 ©2014 JNAS Methodology Abdolhamid Roodini Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Department of Political Science, Sistan and Baluchestan, Zahedan, Iran Corresponding author: Abdolhamid Roodini ABSTRACT: Effective Methodology is an effective theoretical approach from researcher’s point of view. This theoretical approach which defines methodology is also each other’s constraints. Typology is a knowledge which from the past three decades has undergone extensive theoretical changes and also undergone wide changes in the field of methodology. In this article we explain the critical approaches of oriented and post oriented structures and then their comparison. Keywords: Methodology. INTRODUCTION There is no doubt that analyst and researchers use theoretical approach for determining methodology which also semantically determines corpus studies. Typology which was basically introduced in the first three decades of the twentieth century by Saussure and Peres and sued via other analyst for thirty years emerged as the context of macro- structural and pragmatic approach. In this study to verify that the text deals with the structural approach we try to get the textual relations which is the basic approach. The second method under discussion was introduced via Anglo- American scholars on the basis of their own assumption and analysis of structural and post structural approach. CONSTRUCTIVIS METHODOLOGY IN TYOILIGY There is no doubt that oriented structure is considered as a great change in the study of humanity and is a positive aspect. There is a debate that oriented structure is either reading or methodological for bringing order and systemizing human experience in different fields of studies such as linguistics, anthropology, sociology, psychology and literary (Tyson 1999, page 198). -

Interpretation to an Ode by Bidel Based on Riffaterre's Theory

Literary Arts, 11th Year, No. 27, Summer 2019 5 _________________________________________________________________ Interpretation to an Ode by Bidel based on Riffaterre’s Theory Younes Mahmoodzadeh∗ Alireza Mozaffari∗∗ Bahman Nozhat∗∗∗ Abstract Using new methods to analyze poems with particular language is a fundamental requirement. One of these methods is theory of "literary reading" in the process of interpretation of text, especially poetry, which was introduced by Michel Riffater, a French literary critic and professor of poetry in 20th century, in his book "Poem Semiotics". In his opinion, semiotic method helps reader in interpretation and analysis of metaphorical basis of texts, especially in poetry, and reveals hidden semantic layers for him or her. Although Riffater�s method isn�t true in all kinds of poetry especially narrative, it would be helpful in certain types of poetry, especially lyric poems, in our own literature. Here reader travels to mental background of writer or poet through considering level of manifestation of metaphors, conventional poetry�s interpretations and beliefs, hi or her own poetry metaphors and beliefs, exploring semantic infrastructure of text and the magic of vocabulary alignments. He also finds out underlying layers of text, thereby analyzing complex and obscure text. Because Bidel's poem is always associated with consecutive deviation from norms and systematic rules, and through accumulation of lexical and cluster combinations, surprises readers with new metaphor, interpretation of his poems can be a model for explaining poet's plan and mental coherence. This method forces reader to reflect about Bidel's poetry and find new implications of his poetry. This process advances reader mathematically and systematically, and through hypograms, he or she understands and receives final matrix of poetry. -

Umberto Eco's Theory of Architecture Codes

International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development Development Urban and Of Architecture Journal International Vol. 8, No 3, Summer 2018 Explaining the Methods of Architecture Representation Using Semiotic Analysis (Umberto Eco's Theory of Architecture Codes) 1*Seyed Mojtaba Shojaee, 2Seyed Ali Akbar Saremi 1Ph.D student of Architecture, Faculty of Art and Architecture, Islamic Azad Universty, Tehran Center Branch, Tehran, Iran. 2Associated Professor of Architecture, Faculty of Art and Architecture, Islamic Azad Universty, Tehran Center Branch, Tehran, Iran. Recieved 01.01.2017 ; Accepted 16.04.2017 ABSTRACT: In this paper, it is tried to explain the concept of representation and architectural representation through a qualitative methodology, approach its procedure for gradual creation in architecture and then according to scholars and to obtain the effect of this concept in the process of architectural facts the concepts are presented. In addition, it is referred to theories and practical texts by philosophers, and archaeologists and architects who have spoken about the architectural representation, and its definitions are also provided from the perspective of semiotics. Then through a deductive view aiming to clarify the fundamental differences between types of architectural representation and according to the presented ideas, three fundamental roles in the representation of architecture as mimesis and imitation, architectural representation as abstraction and architectural representation as simulation are described and examples are cited for each of them. In the end, by a qualitative methodology and with an interpretive approach using the theory of Umberto Eco in architectural codes, the comparative tables are provided, and to clarify the relationship between the three methods of representation and the procedure of their ideas on the formation of the architectural reality are analyzed through the semiotic approach. -

Analyzing the Quality of Making Sense of the Phenomena: a Study In

Language Related Research E-ISSN: 2383-0816 Vol.11, No.4 (Tome 58), T. M .U. September, October & November 2020 Analyzing the Quality of Making Sense of the Received: 21/05/2020 Accepted: 7/09/2020 Phenomena: A Study in Theosophical Discourse based on Eric Landowski’s Viewpoints ∗ Corresponding Author's E-mail: Atefeh Amirifar 1, Seyed Ali Qasemzadeh2*, Morteza Babak Moein 3 [email protected] 1. PhD Candidate in Mystical Literature, Department of Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Humanities, Imam Khomeini International University, Qazvin, Iran. 2. Associate Professor, Department of Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Humanities, Imam Khomeini International University, Qazvin, Iran. 3. Associate Professor, Department of French Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran. Abstract One of the difficulties for the addressee who encounters theosophical texts is the inability to comprehend the experiences gained by the theosophist. Regardless of language and scientific understanding of linguistic signs, it is impossible to discover how to make sense of the phenomenal world in theosophical discourse. In line with Heidegger who considers language the house of being, the truth of theosophy is also manifested in language; but for some reasons like the inability of language to express experiences, obstacles in the way of understanding the truth and theosophical experiences, the difficult topic and the extraordinarily of theosophist’s experiences, etc. Downloaded from lrr.modares.ac.ir at 15:33 IRST on Saturday September 25th 2021 theosophical language seems difficult and complicated to find. Especially in theosophical discourse, the theosophist/subject as an agent and narrator of theosophy encounters different objects. -

A Study of Underlexicalization in Zoya Pirzad's Novel We Will Get Used to It

Volume 3 Issue 1 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND June 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 A Study of Underlexicalization in Zoya Pirzad’s Novel We Will Get Used to It *Asghar Moulavi Nafchi Senior Lecturer, Hakim Sabzevari University, Iran *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Mohsen Mohammadi Kordiani MA Student of Persian Language and Literature, Hakim Sabzevari University, Iran Ahmadreza Biabani PhD Student of Persian Language and Literature, Hakim Sabzevari University, Iran Abstract The process of human communication and the act of transferring meaning to other individuals are among the most important functions of language. Language is namely a mental system the meaning of which is above all manifested through a sound system. Considering the mental nature of literature, what is employed in the form and structure of a literary work is in great part a mental construct principally originating in the author’s mind, and underlexicalization is a tool used by authors to foreground their writing. The current research studies Zoya Pirzad’s novel, We Will Get Used to It, for the concept of underlexicalization, a term popularized by Roger Fowler, referring to the lack of sufficient vocabulary to express ones meaning and intentions. The reflection of this lexical deficiency, which binds linguistics, literary criticism, and stylistics, is analyzed as it is mirrored in the thoughts and actions of the fictional characters at hand. Keywords: Foregrounding, Underlexicalization, We Will Get Used to It, Zoya Pirzad. http://www.ijhcs.com/index Page 970 Volume 3 Issue 1 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND June 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 1. -

The Semiotic Study of Rag-E Khab from the Peirce's Perspective

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 7, Issue 9, September 2019, PP 1-7 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0709001 www.arcjournals.org The Semiotic Study of Rag-E Khab from the Peirce’s Perspective Dr. Foroogh kazemi1*, Shohreh Dalaee2 1Associate professor of linguistics, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University Tehran, Iran 2M.A of Linguistics, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran *Corresponding Author: Dr. Foroogh kazemi, Associate professor of linguistics, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University Tehran, Iran Abstract: The purpose of this study was to investigate the semiotic aspects of the movie Rag-e Khab. In this research, the film sequences formed the research data, the research method was descriptive-analytic and the data were evaluated based on the Peirce's semiotic view. The present research pursues to answer the questions like which signs are used and how is the representation of gender in these sequences? The findings of the research indicate that in these sequences, in addition to the icon signs, index signs are used more and the symbolic signs are used lesser. The results also revealed that the representation of gender in this film is female-centered and portrayed women's lives and their problems. Keywords: Peirce's semiotic view, Types of signs, Rag-e Khab movie. 1. INTRODUCTION Semiotics is a science that studies the structures of signs. This branch of science has been used since the 1950s as a research method in recognizing the signification and perceptions of communication functions.