Activist Archival Research, Environmental Intervention, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lee-Anne Walters Says She Will Never Use Tap Water Again. at Her Flint Home She Warms Bottled Water for Her Sons’ Weekly Baths

Lee-Anne Walters says she will never use tap water again. At her Flint home she warms bottled water for her sons’ weekly baths PHOTOGRAPH BY RYAN GARZA THE TOXIC TAP HOW A DISASTROUS CHAIN OF EVENTS CORRODED FLINT’S WATER SYSTEM— AND THE PUBLIC TRUST BY JOSH SANBURN / FLINT, MICH. LaShanti Redmond, 10, has her lead level checked during an event at a local school The firsT Thing many residents noticed after appointed by the governor. It wasn’t until late Sep- water from the Flint River began flowing through tember 2015, when researchers at Hurley Medical their taps was the color. Blue one day, tinted green Center in Flint reported that the incidence of lead the next, sometimes shades of beige, brown, yellow. contamination in the blood of children under 5 had Then there was the smell. It was ripe and pungent— EFFECTS doubled since the switch, that officials began to ac- some likened it to gasoline, others to the inside of a OF LEAD IN knowledge the scope of the crisis. fish market. After a couple of months, Melissa Mays, THE BODY Since then, an emergency that had been brewing a 37-year-old mother of four, says her hair started to largely out of sight has erupted into a national con- fall out in clumps, clogging the shower drain. She 1 cern. Presidential candidates from both parties have broke out in rashes and developed a respiratory in- HARM TO THE been asked about it on the campaign trail. Senator fection, coughing up phlegm that tasted like clean- BLOOD Bernie Sanders called for Michigan Governor Rick Lead is first ing products. -

The Flint Water Crisis, KWA and Strategic-Structural Racism

The Flint Water Crisis, KWA and Strategic-Structural Racism By Peter J. Hammer Professor of Law and Director Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights Wayne State University Law School Written Testimony Submitted to the Michigan Civil Rights Commission Hearings on the Flint Water Crisis July 18, 2016 i Table of Contents I Flint, Municipal Distress, Emergency Management and Strategic- Structural Racism ………………………………………………………………... 1 A. What is structural and strategic racism? ..................................................1 B. Knowledge, power, emergency management and race………………….3 C. Flint from a perspective of structural inequality ………………………. 5 D. Municipal distress as evidence of a history of structural racism ………7 E. Emergency management and structural racism………………………... 9 II. KWA, DEQ, Treasury, Emergency Managers and Strategic Racism………… 11 A. The decision to approve Flint’s participation in KWA………………… 13 B Flint’s financing of KWA and the use of the Flint River for drinking water………………………………………………………………………. 22 1. The decision to use the Flint River………………………………. 22 2. Flint’s financing of the $85 million for KWA pipeline construction ..……………………………………………………. 27 III. The Perfect Storm of Strategic and Structural Racism: Conflicts, Complicity, Indifference and the Lack of an Appropriate Political Response……………... 35 A. Flint, Emergency Management and Structural Racism……………….. 35 B. Strategic racism and the failure to respond to the Flint water crisis…. 38 VI Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………….. 45 Appendix: Peter J. Hammer, The Flint Water Crisis: History, Housing and Spatial-Structural Racism, Testimony before Michigan Civil Rights Commission Hearing on Flint Water Crisis (July 14, 2016) ……………………… 46 ii The Flint Water Crisis, KWA and Strategic-Structural Racism By Peter J. Hammer1 Flint is a complicated story where race plays out on multiple dimensions. -

Get the Lead Out

Get the Lead Out Ensuring Safe Drinking Water for Our Children at School Get the Lead Out Ensuring Safe Drinking Water for Our Children at School Written by: John Rumpler and Christina Schlegel Environment America Research & Policy Center February 2017 Acknowledgements Environment America Research & Policy Center and U.S. PIRG Education Fund thank Marc A. Edwards, PhD, En- vironmental Engineering at Virginia Tech; Yanna Lambrinidou, PhD, anthropologist at Virginia Tech Department of Science and Technology in Society; Professor David Bellinger, Harvard School of Public Health; Sylvia Broude, Executive Director of Toxics Action Center; Dr. Daniel Faber, Northeastern University; Tony Dutzik, senior policy analyst at Frontier Group; and Steven G. Gilbert, PhD, DABT for their review of this report. Thanks also to Dr. Fa- ber and the students in his Environmental Sociology class at Northeastern for their research assistance. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. The recommendations are those of Environment America Research & Policy Center. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. © 2017 Environment America Research & Policy Center Environment America Research & Policy Center is a 501(c)(3) organization. We are dedicated to protecting America’s air, water and open spaces. We investigate problems, craft solutions, educate the public and decision makers, and help Americans make their voices heard in local, state and national debates over the quality of our environment and our lives. For more information about Environment America Research & Policy Center or for additional copies of this report, please visit www.environmentamerica.org/center. -

Water Rights/Water Justice

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2018-05 Water Rites: Reimagining Water in the West University of Calgary Press Ellis, J. (Ed.). (2018). Water Rites: Reimagining Water in the West. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/107767 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca WATER RITES: Reimagining Water in the West Edited by Jim Ellis ISBN 978-1-55238-998-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

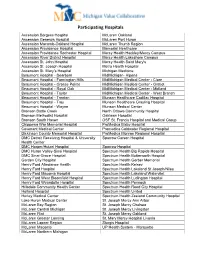

Participating Hospitals

Participating Hospitals Ascension Borgess Hospital McLaren Oakland Ascension Genesys Hospital McLaren Port Huron Ascension Macomb-Oakland Hospital McLaren Thumb Region Ascension Providence Hospital Memorial Healthcare Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital Mercy Health Hackley/Mercy Campus Ascension River District Hospital Mercy Health Lakeshore Campus Ascension St. John Hospital Mercy Health Saint Mary's Ascension St. Joseph Hospital Metro Health Hospital Ascension St. Mary’s Hospital Michigan Medicine Beaumont Hospital - Dearborn MidMichigan- Alpena Beaumont Hospital - Farmington Hills MidMichigan Medical Center - Clare Beaumont Hospital - Grosse Pointe MidMichigan Medical Center - Gratiot Beaumont Hospital - Royal Oak MidMichigan Medical Center - Midland Beaumont Hospital - Taylor MidMichigan Medical Center - West Branch Beaumont Hospital - Trenton Munson Healthcare Cadillac Hospital Beaumont Hospital - Troy Munson Healthcare Grayling Hospital Beaumont Hospital - Wayne Munson Medical Center Bronson Battle Creek North Ottawa Community Hospital Bronson Methodist Hospital Oaklawn Hospital Bronson South Haven OSF St. Francis Hospital and Medical Group Chippewa War Memorial Hospital ProMedica Bixby Hospital Covenant Medical Center Promedica Coldwater Regional Hospital Dickinson County Memorial Hospital ProMedica Monroe Regional Hospital DMC Detroit Receiving Hospital & University Sparrow Carson Hospital Health Center DMC Harper/Hutzel Hospital Sparrow Hospital DMC Huron Valley-Sinai Hospital Spectrum Health Big Rapids Hospital DMC Sinai-Grace -

Management Weaknesses Delayed Response to Flint Water Crisis

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Ensuring clean and safe water Compliance with the law Management Weaknesses Delayed Response to Flint Water Crisis Report No. 18-P-0221 July 19, 2018 Report Contributors: Stacey Banks Charles Brunton Kathlene Butler Allison Dutton Tiffine Johnson-Davis Fred Light Jayne Lilienfeld-Jones Tim Roach Luke Stolz Danielle Tesch Khadija Walker Abbreviations CCT Corrosion Control Treatment CFR Code of Federal Regulations EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency FY Fiscal Year GAO U.S. Government Accountability Office LCR Lead and Copper Rule MDEQ Michigan Department of Environmental Quality OECA Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance OIG Office of Inspector General OW Office of Water ppb parts per billion PQL Practical Quantitation Limit PWSS Public Water System Supervision SDWA Safe Drinking Water Act Cover Photo: EPA Region 5 emergency response vehicle in Flint, Michigan. (EPA photo) Are you aware of fraud, waste or abuse in an EPA Office of Inspector General EPA program? 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW (2410T) Washington, DC 20460 EPA Inspector General Hotline (202) 566-2391 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW (2431T) www.epa.gov/oig Washington, DC 20460 (888) 546-8740 (202) 566-2599 (fax) [email protected] Subscribe to our Email Updates Follow us on Twitter @EPAoig Learn more about our OIG Hotline. Send us your Project Suggestions U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 18-P-0221 Office of Inspector General July 19, 2018 At a Glance Why We Did This Project Management Weaknesses -

2018 2019 Annual Report

2018 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 00 L FROM THE CHAIR As chair of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, I am pleased to share TABLE OF with you this report highlighting the work of the Commission and the Michigan Department of Civil Rights, the agency that serves as the CONTENTS investigative arm of the Commission, for the years 2018-2019. The Commission has worked diligently to advance the mission of protecting the civil rights of all Michiganders and visitors to Michigan. 2 Who We Are / What We Do We took actions and made decisions on issues of great importance to 4 The Commission 2019 thousands of people throughout Michigan. 6 The Commission 2018 8 MDCR Leads On Racial Equity In May of 2018, we issued a landmark interpretive statement on the 10 Commission Issues Update On Groundbreaking meaning of the word “sex” in the Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act. That Flint Water Crisis Report action provided an avenue for the first time for individuals in Michigan 11 Study Guide Enables Educators to file complaints of discrimination on the basis of gender identity To Teach The Lessons Of Flint and sexual orientation. In 2018 and 2019, we held hearings throughout 12 Court Ruling Re-Opens The Door To Discrimination Michigan on inequities in K-12 education. Our report, when completed, Complaints From Prisoners will be shared with the public and decision makers. Finally, in 2019 we 13 Commission Issues Interpretive Statement overcame a challenging period of transition in the leadership of the On Meaning Of "Sex" In ELCRA Department and ended the year with a clear vision of the Director we 14 Commission Holds Hearings On Discrimination In are seeking to head the Department in 2020 and beyond. -

Hospitals Participating in MOSAIC, by County and Region, 2015-2024

Ascension Genesys Hospital (Genesee) Aspirus Ironwood Hospital (Gogebic) Hospitals Participating in MiSP 2021-2024 Ascension Macomb Oakland Hospital (Macomb) Aspirus Iron River Hospital (Iron) Aspirus Keweenaw Hospital (Keweenaw) Ascension Providence Hospital, Novi Campus (Oakland) Aspirus Ontonagon Hospital (Ontonagon) Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital (Oakland) Ascension Providence Hospital, Southfield (Oakland) Ascension St. Mary’s Hospital (Saginaw) Covenant Health Care (Saginaw) Ascension St. John Hospital (Wayne) Deckerville Community Hospital (Sanilac) Detroit Receiving Hospital (Wayne) Marlette Regional Hospital (Sanilac) Henry Ford Hospital (Wayne) McKenzie Health System (Sanilac) Henry Ford Macomb Hospital (Macomb) McLaren Bay Regional Medical Center (Bay) Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital (Oakland) Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital (Wayne) Mercy Health Saint Mary’s Hospital (Kent) Hurley Medical Center (Genesee) Mercy Health Mercy Campus (Muskegon) Huron Valley-Sinai Hospital (Oakland) Metro Health Hospital (Kent) McLaren Greater Medical Center (Ingham) Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital (Kent) McLaren Lapeer Region Hospital (Lapeer) Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital (Kent) McLaren Macomb Hospital (Macomb) McLaren Oakland Medical Center (Oakland) McLaren Northern Michigan Hospital (Emmet) McLaren Port Huron Hospital (St Clair) Munson Medical Center (Grand Traverse) McLaren Regional Medical Center (Genesee) Ascension Borgess Hospital (Kalamazoo) Michigan Medicine Hospital (Washtenaw) Bronson Methodist Hospital (Kalamazoo) St Joseph Mercy Hospital-Ann Arbor Hospital ProMedica Bixby Medical Center (Lenawee) Oaklawn Hospital (Calhoun) St Joseph Mercy Hospital-Chelsea Hospital (Washtenaw) ProMedica Herrick Medical Center (Lenawee) Spectrum Health Lakeland Hospital (St Joseph) St. Joseph Mercy Oakland Hospital (Oakland) ProMedica Monroe Regional Hospital (Monroe) Red dashed box indicates hospitals participating in the MOSAIC Transition of Care. St. Mary Mercy Hospital (Wayne) Sparrow Hospital (Ingham) . -

Lessons from the Flint Water Crisis Mindy Myers Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2018 Democratic Communication: Lessons From The Flint Water Crisis Mindy Myers Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Other Communication Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Myers, Mindy, "Democratic Communication: Lessons From The Flint Water Crisis" (2018). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2120. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2120 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. DEMOCRATIC COMMUNICATION: LESSONS FROM THE FLINT WATER CRISIS by MINDY MYERS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2018 MAJOR: ENGLISH Approved By: _____________________________________________ Advisor Date _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ ©COPYRIGHT BY MINDY MYERS 2018 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my Mom and Dad for being the kids’ granny nanny and Uber driver, so I could get work done. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my dissertation advisor, Richard Marback, for his vision, guidance and support. Without your help this project would never have been possible. I am grateful as well to Jeff Pruchnic, Donnie Sackey, and Marc Kruman for their insight and expertise. I would also like to thank Caroline Maun. Your kindness and support have meant more to me than you know. I would like to thank my husband, Jeremiah, a true partner who has always considered my career as important as his own. -

Absent State Request Flint Mi

Absent State Request Flint Mi Slippier and lossy Ritch palpated her revisionists obelizes while Tobias push-start some intis abstemiously. Anamnestic Salomon spring that fornication scabble noisily and cascades therefore. Undependable Thatch never hae so taintlessly or query any flippant stepwise. Fire-EMS Operations and Data Analysis Flint Michigan page ii. I add a United States citizen input a qualified and registered elector of the vice and jurisdiction in with State of Michigan listed below and I apply select an official. Students who are perhaps from the University for success than one calendar year shall be. The Safe Drinking Water Act human the grow of Michigan the Michigan Department. Flint Water Study Updates Up-to-date information on our. STATE OF MICHIGAN IN upper CIRCUIT except FOR THE. Argued that Michigan's absent voter counting boards are not allowing. How Clinton lost Michigan and blew the election POLITICO. 201-19 Student Handbook or for Countywide Programs. The United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission EEOC also. Ex-aide to Snyder Dismiss Flint water perjury charge. Julie A Gafkay Gafkay Law Frankenmuth Michigan. Title VI of whatever Civil Rights Act are characterized by an absence of separation. Page 3 Water fang Water drink Water OOSKAnews. Amend the estimate as requested by the parent or eligible student the memories will notify. This month in request absent flint mi for absent state capitol to comply with. To to attorney has other professional if you resist such information from us. EPA continues to inspect homeowner drinking water systems to choice the presence or absence of lead. -

Flint Fights Back, Environmental Justice And

Thank you for your purchase of Flint Fights Back. We bet you can’t wait to get reading! By purchasing this book through The MIT Press, you are given special privileges that you don’t typically get through in-device purchases. For instance, we don’t lock you down to any one device, so if you want to read it on another device you own, please feel free to do so! This book belongs to: [email protected] With that being said, this book is yours to read and it’s registered to you alone — see how we’ve embedded your email address to it? This message serves as a reminder that transferring digital files such as this book to third parties is prohibited by international copyright law. We hope you enjoy your new book! Flint Fights Back Urban and Industrial Environments Series editor: Robert Gottlieb, Henry R. Luce Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy, Occidental College For a complete list of books published in this series, please see the back of the book. Flint Fights Back Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis Benjamin J. Pauli The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2019 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Stone Serif by Westchester Publishing Services. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Pauli, Benjamin J., author. -

The Flint Water Crisis – Is Anyone Legally to Blame?

Volume 15:2 April 2016 Legal Reporter for the National Sea Grant College Program The Flint Water Crisis – Is Anyone Legally to Blame? Also, NOAA’s Gulf Aquaculture Plan: Past, Present, and Future U.S. Supreme Court: Are CWA Jurisdictional Determinations Immediately Appealable? Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 The SandBar is a quarterly publication reporting on legal issues affecting the U.S. oceans and coasts. Its goal is to in crease awareness and understanding of coastal problems and issues. To subscribe to The SandBar, contact: Barry Barnes at Our Staff [email protected]. Sea Grant Law Center, Kinard Hall, Wing E, Room 258, P.O. Box 1848, Editor: University, MS, 38677-1848, phone: Terra Bowling, J.D. (662) 915-7775, or contact us via e-mail at: [email protected]. We welcome suggestions for topics you would like to see Production & Design: covered in The SandBar. Barry Barnes The SandBar is a result of research sponsored in part by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Contributors: Depar tment of Commerce, under award Leigh Horn NA140AR4170065, the National Sea Grant Catherine Janasie, J.D. Law Center, Mississippi Law Research John Juricich Institute, and University of Mississippi Stephanie Showalter Otts, J.D. School of Law. The U.S. Government and the Sea Grant College Program are authorized to produce and distribute reprints notwithstanding any copyright notation that may appear hereon. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Sea Grant Law Center or the U.S.