Oral History Transcript T-0019, Interview with Henry Armstrong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 1, 2019

Colchester History Connections Newsletter September 1,2019 Colchester Historical Society, Box 112, Downsville, New York 13755 Volume 9, Issue 4 Preserving the history of Downsville, Corbett, Shinhopple, Gregorytown, Horton and Cooks Falls Website: www.colchesterhistoricalsociety.org Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/colchesternyhistorian/ Historical Society Room, 72 Tannery Road, Downsville, New York is open by appointment, please call Kay Parisi-Hampel, Town Historian at 607-363-7303 2020 Historical Society Calendar This year’s 33-page calendar features black and white photographs of Colchester’s Civic and Social Clubs Colchester Historical Society 2020 Calendar Colchester’s Civic and Social Clubs Celebrating 100 years of the James S Moore, Post 167 American Legion and features a special page celebrating the 100th anniversary of the James S. Moore Post 167 American Legion and a Photo Name Key. Calendars are $15 and available at Colchester Town Hall, The Downsville Diner, and on-line through the Historical Society website. Proceeds from the calendar will be used to conserve the artifacts and documents of the Historical Society and educational programming. Colchester Town Hall Display September 30-December, 2019 Downsville Central School--80th Anniversary of the Consolidation of Colchester One-room Schools The Story Behind the Consolidation of Colchester’s schools In 1937 the Board of Trustees for the Downsville Union Free School were given an ultimatum by the State Education Department, “Build or equip forthwith an adequate gymnasium for the Downsville High School or lose the $13,000 state aid received. Or, plan immediately for centralizing the Downsville high school by taking in 17 other adjacent districts and the erection of a Central school likely to cost a quarter of a million dollars Failing to set on foot plans for one or the other of these alternative projects will result, as stated, in loss of the state aid now received and the removal of the trustees”. -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

|||GET||| Max Baer and Barney Ross Jewish 1St Edition

MAX BAER AND BARNEY ROSS JEWISH 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Jeffrey Sussman | 9781442269323 | | | | | A Book About Jewish Boxers and Anti-Semitism He often got into fistfights with anti-Semites. Silver Star. Books by Jeffrey Sussman. November 23, There is speculation that Capone bought up tickets to his early fights, knowing some of that money would be funneled to Dov. The extraordinary cast of characters includes Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who praised Hitler and Mussolini but thought Winston Churchill "one of the most dangerous men I have ever known"; Maurice Duplessis, who padlocked the homes of private citizens for their political opinions; and Tim Buck, the Communist leader who narrowly escaped murder in Kingston Penitentiary. Max Baer and Barney Ross Jewish 1st edition Venner. They told him he could earn a lot of money and be a symbol of strength for the Jewish community. Black Dynamite Black Dynamite Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Ross and more than a dozen others were world champion title holders. Griffith Stadium, Washington. Wikimedia Commons. Jackie Davis. Lou Halper. While recovering from war wounds and malaria he became addicted to morphine, but with fierce effort he ultimately kicked his habit and then campaigned fervently against drug abuse. Lightweight Light Welterweight Welterweight. Ross and more than a dozen others were world champion titleholders. Ross in When I told this story to boxing writer, Peter Wood, an English teacher who had been a Golden Gloves boxer, he suggested I begin writing Max Baer and Barney Ross Jewish 1st edition boxing for a website, www. -

University Press, 1965+

Inventory of the University Press Records in the Northern Illinois University Archives UA 33 INTRODUCTION The University Archives acquired material from the University Press in several installments from 1968 to 1978. Current publications are received regularly. There are no restrictions on access to the collection. 22 boxes 22.75 linear feet 1 9 6 5- SCOPE AND CONTENT The University Press records consist primarily of the Press’s publications. There are several folders of information on the formative years, 1965-1975. For additional information, researchers should consult the Presidents' Papers, the Provosts' Administrative Records and the records of the College of Education in the University Archives. HISTORICAL SKETCH The University Council approved the establishment of a University Press on May 3, 1965. By November of that year faculty members were being asked to serve on the University Press Board and the search for a Director of the Press was being organized. The Board held its first meeting on May 26, 1966, and the first publication came out in 1967. COLLECTION INVENTORY BOX FOLDER DESCRIPTION SERIES I: Records of the Press 1 1 Organization, Establishment, and History, (1965-2009) 2 Report to the Board of Regents, June, 1979 3 Board Minutes, 1966-1974 4 Sales Reports and Statements of Income and Expenses, 1968-1973 5 Correspondence, 1968-1978 6 American Association of University Presses, January 1971-March 1972 7 Support Function Review, University Press, FY 1988 8 Directors: Mary Lincoln (1980-2007), J. Alex Schwartz (2007- 2 1-2b Catalogs, (1969-2009) 3 Flyers and General Mailings, 1972, 1973, 1978 UA 33 - University Press Page 2 BOX FOLDER DESCRIPTION 2 4 Chicago Book Clinic and Midwestern Books Competition Awards, 1970- 1976 5-8 Chicago Book Clinic, 1968-1976 9 American Association of University Presses Book Show, 1977 SERIES II: Publications of the Press BOX YEAR TITLE 3 1967 Kallich, Martin I., Heaven's First Law: Rhetoric and Order in Pope’s Essay on Man. -

W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies Celebrates Its 40Th Anniversary Drawing by Nelson Stevens

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE W.E.B. DU BOIS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES UMASS AMHERST 2009—2010 W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies Celebrates Its 40th Anniversary Drawing by Nelson Stevens Inside this issue: Faculty News 2 Class of 2010 3 Meet our Graduate Students 4 Graduate Student News & 8 Views Black Poetry of the 60s & 70s 9 Alumni News 10 Fall 2011 Courses 11 TAKE NOTE: We’re on the Web at www.umass.edu/afroam Phone: 413-545-2751 Fax: 413-545-0628 PAGE 2 DU BOIS LINES PROFESSOR STEVEN TRACY LECTURES IN CHINA “Syncopating Heroes in Sterling Brown’s Poetry,” was attended by 250-300 graduate students and faculty….. dren, who were very inquisitive about the strange man with the strange instrument. Scholars from all over China attended the conference, which featured panels and papers with on a variety of subjects in American studies. Steve's talk on the second day, "Without Respect for Gender," preceded by "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" rofessor Steve Tracy returned to China for his second visit in honor of Obama's rise to the presidency, was well received, P in October 2009. Invited by Central China Normal Univer- and has been accepted for publication in Foreign Literature sity (CCNU) to lecture and Zheijiang Normal University to de- Studies (FLS). At dinner the second night, Steve found himself liver a keynote address, Steve spent six days in China talking sitting at a table with all women (the night before it had been with students and professors and sightseeing at cave sites and all men) taking some good-natured ribbing regarding his man- monuments in Central China. -

Dec Pages 79-84.Qxd 8/5/2019 12:45 PM Page 1

ASC080119_080_Dec Pages 79-84.qxd 8/5/2019 12:45 PM Page 1 All Star Cards To Order Call Toll Free Page 86 15074 Antioch Road Overland Park, KS 66221 www.allstarcardsinc.com (800) 932-3667 BOXING 1927-30 EXHIBITS: 1938 CHURCHMAN’S: 1951 TOPPS RINGSIDE: 1991 PLAYERS INTERNATIONAL Dempsey vs. Tunney “Long Count” ...... #26 Joe Louis PSA 8 ( Nice! ) Sale: $99.95 #33 Walter Cartier PSA 7 Sale: $39.95 (RINGLORDS): ....... SGC 60 Sale: $77.95 #26 Joe Louis PSA 7 $69.95 #38 Laurent Dauthuille PSA 6 $24.95 #10 Lennox Lewis RC PSA 9 $17.95 Dempsey vs. Tunney “Sparing” ..... 1939 AFRICAN TOBACCO: #10 Lennox Lewis RC PSA 8.5 $11.95 ....... SGC 60 Sale: $77.95 NEW! #26 John Henry Lewis PSA 4 $39.95 1991 AW SPORTS BOXING: #13 Ray Mercer RC PSA 10 Sale: $23.95 #147 Muhammad Ali Autographed (Black #14 Michael Moorer RC PSA 9 $14.95 1935 PATTREIOUEX: 1948 LEAF: ....... Sharpie) PSA/DNA “Authentic” $349.95 #31 Julio Cesar-Chavez PSA 10 $29.95 #56 Joe Louis RC PSA 5 $139.95 #3 Benny Leonard PSA 5 $29.95 #33 Hector “Macho” Camacho PSA 10 $33.95 #78 Johnny Coulon PSA 5 $23.95 1991 AW SPORTS BOXING: #33 Hector “Macho” Camacho PSA 9 $17.95 1937 ARDATH: 1950 DUTCH GUM: #147 Muhammad Ali Autographed (Black NEW! Joe Louis PSA 7 ( Tough! ) $99.95 ....... Sharpie) PSA/DNA “Authentic” $349.95 1992 CLASSIC W.C.A.: #D18 Floyd Patterson RC PSA $119.95 Muhammad Ali Autographed (with ..... 1938 CHURCHMAN’S: 1951 TOPPS RINGSIDE: 1991 PLAYERS INTERNATIONAL ...... -

Cameras at Work: African American Studio Photographers and the Business of Everyday Life, 1900-1970

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 Cameras at Work: African American Studio Photographers and the Business of Everyday Life, 1900-1970 William Brian Piper College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Piper, William Brian, "Cameras at Work: African American Studio Photographers and the Business of Everyday Life, 1900-1970" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1477068187. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2SG69 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cameras at Work: African American Studio Photographers and the Business of Everyday Life, 1900-1970 W. Brian Piper Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2006 Bachelor of Arts, University of Virginia, 1998 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August, 2016 © Copyright by William Brian Piper 2016 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the professional lives of African American studio photographers, recovering the history of an important industry in African American community life during segregation and the long Civil Rights Movement. It builds on previous scholarship of black photography by analyzing photographers’ business and personal records in concert with their images in order to more critically consider the circumstances under which African Americans produced and consumed photographs every day. -

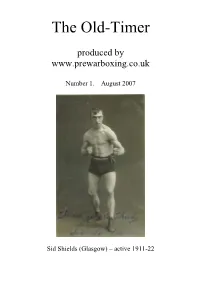

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

Sugar Ray Robinson

SPORTING LEGENDS: SUGAR RAY ROBINSON SPORT: BOXING COMPETITIVE ERA: 1940 - 1965 Walker Smith Jr. (May 3, 1921 - April 12, 1989), better known in the boxing world as Sugar Ray Robinson, was a boxer who was a native of Detroit, Michigan. Robinson is the holder of many boxing records, including the one for the most times being a champion in a division, when he won the world Middleweight division title 5 times. He also won the world Welterweight title once. Robinson is regarded by many boxing fans and critics as the best boxer of all time. His supporters argue that while Muhammad Ali did more for the sport on a social scale, Robinson had a better style. Ali has said without hesitation many times that he feels that Robinson is the greatest fighter of all time, Ali simply considers himself to be the greatest Heavyweight Champion. During the 1940s and 1950s, Robinson appeared several times on the cover of Ring Magazine, and he joined the Army for some time. Robinson made his debut in 1940, knocking out Joe Eschevarria in 2 rounds. He built a record of 40 wins and 0 losses before facing Jake LaMotta, in a 10 round bout. The bout, which was portrayed in the Hollywood movie Raging Bull (which was based on LaMotta's life), was the second of six fights between these opponents, and LaMotta dropped Robinson, eventually beating him by decision. Robinson had won their first bout and would go on to win the next four. Between his debut fight and the second LaMotta bout, Robinson had also beaten former world champions Sammy Angott, Fritzie Zivic and Marty Servo. -

Boxing Men: Ideas of Race, Masculinity, and Nationalism

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Boxing Men: Ideas Of Race, Masculinity, And Nationalism Robert Bryan Hawks University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hawks, Robert Bryan, "Boxing Men: Ideas Of Race, Masculinity, And Nationalism" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1162. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1162 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOXING MEN: IDEAS OF RACE, MASCULINITY, AND NATIONALISM A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of Mississippi's Center for the Study of Southern Culture by R. BRYAN HAWKS May 2016 Copyright © 2016 by R. Bryan Hawks ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Jack Johnson and Joe Louis were African American boxers who held the title of World Heavyweight Champion in their respective periods. Johnson and Louis constructed ideologies of African American manhood that challenged white hegemonic notions of masculinity and nationalism from the first decade of the twentieth century, when Johnson held the title, through Joe Louis's reign that began in the 1930's. This thesis investigates the history of white supremacy from the turn of the twentieth century when Johnson fought and does so through several lenses. The lenses I suggest include evolving notions of masculinity, Theodore Roosevelt's racially deterministic agendas, and plantation fiction. -

June 2019 BOB EDITED

June 2019 "Rick" CH CT OTCH MACH HC VCCH UCH UOCH UUDX UROG URX2 EN C-ATCH ARCHMX Skyland Ricochet UDX10 OGM VST TDX TDU PUDX VER GN GO RAE2 HXAsd HXBsd MXS MJB MFB T2B SWA SCM SIE SEE CGCA CGCU TKN FDC, EAC OJC WV-N TN-N NCC, RL1X3 RL2X3 RL3X3 RLVX RL3-AOE RLV-AOE RL2-AOE RL1-AOE, NW1 Owned by : Gerianne Darnell "Rick" Photo byRon Puckett Quintuple Champion! by Gerianne Darnell Photo by Michelle Thorsteinson Photo byCorey LeGrand CH CT OTCH MACH HC VCCH UCH UOCH UUDX UROG URX2 EN C-ATCH ARCHMX Skyland Ricochet UDX10 OGM VST TDX TDU PUDX VER GN GO RAE2 HXAsd HXBsd MXS MJB MFB T2B SWA SCM SIE SEE CGCA CGCU TKN FDC, EAC OJC WV-N TN-N NCC, RL1X3 RL2X3 RL3X3 RLVX RL3-AOE RLV-AOE RL2-AOE RL1-AOE, NW1 Who says that lightening can't strike twice? In 2012 I was thrilled to finish my first AKC Quintuple Champion (CH CT OTCH MACH HC) on my lovely female Border Collie, Riva. Riva finished her CT to complete her Quint the day after Rick finished his OTCH to become a Triple Champion. That was an amazing weekend! I hoped at the time that Rick would also some day finish his Quintuple Championship, but so many things would have to fall in to place again, including a willing dog who would stay in good health for many years to come. And, lucky me, it has happened again! Rick has been such an incredible dog. He was the son of one of my heart dogs, DC Raymond UDT. -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan