Race & Criminal Injustice Theme Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EX ALDERMAN NEWSLETTER 137 and UNAPPROVED Chesterfield 82 by John Hofmann July 26, 2014

EX ALDERMAN NEWSLETTER 137 and UNAPPROVED Chesterfield 82 By John Hofmann July 26, 2014 THIS YEAR'S DRIVING WHILE BLACK STATS: For some reason the Post-Dispatch did not decide to do a huge article on the Missouri Attorney General's release of Vehicle Traffic Stop statistical data dealing with the race of drivers stopped by police. The stats did not change that much from last year. Perhaps the Post-dispatch is tired of doing the same story over and over or finally realized that the statistics paint an unfair picture because the overall region's racial breakdown is not used in areas with large interstate highways bringing hundreds of thousands of people into mostly white communities. This does not mean profiling and racism doesn't exist, but is not as widespread as it was 30 years ago. Traffic stop statistics for cities are based on their local populations and not on regional populations. This can be blatantly unfair when there are large shopping districts that draw people from all over a region or Interstate highways that bring people from all over the region through a community. CHESTERFIELD: Once again the Chesterfield Police come off looking pretty good. The four largest racial groups in Chesterfield are: Whites (84%) Asians (9%), Hispanics (2.9%) and Blacks (2.6%). If you believe in these statistics they show the Chesterfield Police are stopping too many whites and blacks and not stopping enough Asians and Hispanics. That is what is wrong with the Missouri Collection of Traffic data. The County wide population data comes into play since there is a major Interstate Highway going through Chesterfield and four major shopping districts. -

September 1, 2016 TO: the Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon FR: Angela Wilhelms, Secretary of the University RE: No

September 1, 2016 TO: The Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon FR: Angela Wilhelms, Secretary of the University RE: Notice of Board Meeting The Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon will hold a meeting on the date and at the location set forth below. Topics at the meeting will include: a recommendation regarding Dunn Hall; seconded motions and referrals from September 8, 2016, committee meetings; presidential report; presidential assessment report; AY16‐17 tuition and fee setting‐process; “Clusters of Excellence” in focus; federal funding; and an update on UO Portland. The meeting will occur as follows: Thursday, September 8, 2016 – 2:00 pm Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom Friday, September 9, 2016 – 9:30 am Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom The meeting will be webcast, with a link available at www.trustees.uoregon.edu/meetings. The Ford Alumni Center is located at 1720 East 13th Avenue, Eugene, Oregon. If special accommodations are required, please contact Amanda Hatch at (541) 346‐3013 at least 72 hours in advance. BOARD OF TRUSTEES 6227 University of Oregon, Eugene OR 97403‐1266 T (541) 346‐3166 trustees.uoregon.edu An equal‐opportunity, affirmative‐action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon Public Meeting September 8-9, 2016 Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8 – 2:00 pm – Convene Public Meeting - Call to order, roll call, verification of quorum - Approval of June 2016 minutes (Action) - Public comment Those wishing to provide comment must sign up advance and review the public comment guidelines either online (http://trustees.uoregon.edu/meetings) or at the check-in table at the meeting. -

What Happened in Missouri? America's Most Controversial Medical Marijuana Licensing Process Explained

What Happened in Missouri? America’s Most Controversial Medical Marijuana Licensing Process Explained Cannabis Consumers Coalition, October 29, 2020 Executive Summary: The struggle to control medical marijuana licenses & market share in Missouri has been hotly contested since at least 2014. This has led to 5 diverging campaign groups differing over access to licensing and strategy during the time period 2014-2018. In November 2018, Missouri voters approved New Approach Missouri’s initiative petition, Constitutional Amendment 2, implementing medical marijuana in Missouri (now Amendment XIV to the Missouri Constitution). In January 2020, some 1800 out of 2200 license applications were denied, sparking a public controversy & legislative investigations into the process. Founder Larisa Bolivar About Us The Cannabis Consumers Coalition (registered as CCU) is a federally recognized 501(c)(3) consumer advocacy organization that acts as a consumer watchdog in the cannabis industry. Protecting the consumer is at the heart of what we stand for and we do this by helping to create an ethical cannabis industry through advocacy, activism, education, and policy work. Consumers are who voted for cannabis legalization and it is in our power to ensure that we have an industry that puts consumers’ needs above all else based on sound market research via political and social advocacy. As a membership organization, we work collectively to educate consumers and the general public. The Cannabis Consumers Coalition strives to set industry standards in the areas of public safety, quality control, pricing, pesticide and fertilizer use, labeling, testing, customer service, ethical business practices, consumer rights in the workplace, and any emerging issues impacting cannabis consumers. -

ARMED FORCES 1St Pitch, June 17 Dispatchsan Diego Navy/Marine Corps Dispatch 619.280.2985 FIFTY SEVENTH YEAR NO

Weekly Contest AutoMatters & More Around Town & Concerts Here’s your chance to save up to $300 This week, join Jan Wagner for The State of Check out our latest entertainment guide, when you enter to win four Knott’s Berry Formula 1 and ‘Cars 3’. happenings and concerts in the local area. Farm tickets. See page 5 See page 17 See pages 22 & 23 Navy Marine Corps Coast Guard Army Air Force AT AT EASE ARMED FORCES 1st pitch, June 17 DISPATCHSan Diego Navy/Marine Corps Dispatch www.armedforcesdispatch.com 619.280.2985 FIFTY SEVENTH YEAR NO. 1 Serving active duty and retired military personnel, veterans and civil service employees THURSDAY, JUNE 15, 2017 Photo by McPhedran The history of Father’s Day in the United States There are two stories of when the first Father’s Day was celebrated. According to some accounts, the first In this April 26 file photo, service members and civil- Father’s Day was celebrated ians gathered to observe Denim Day at Naval Sup- in Washington state on June port Activity Bethesda. The event was a Army led 19, 1910. A woman by the program focused on sexual assault prevention. Navy name of Sonora Smart Dodd photo by MC3 William Phillips came up with the idea of honoring and celebrating her father while listening to DoD launches online program a Mother’s Day sermon at church in 1909. She felt as to help military survivors of though mothers were getting all the acclaim while fathers sexual abuse, assault were equally deserving of WASHINGTON - The Defense Department launched an online a day of praise (She would and mobile educational program June 13 to help individuals begin probably be displeased that to recover, heal and build resiliency after a sexual assault. -

2MFM Newsletter 12 2020

DECEMBER QUERIES DECEMBER 2020 How do our social and economic choices help or harm our vulnerable neighbors? The Multnomah Friends Meeting Do we consider whether the seeds of war and the displacement of peoples Monthly have nourishment in our lifestyles and possessions? Newsletter How does the Spirit guide us in our relationship to money? 4312 SE STARK STREET, PORTLAND, OREGON 97215 (503) 232-2822 WWW.MULTNOMAHFRIENDS.ORG FRIENDLY FACES: Sisters Alegría and Confianza of Las Amigas Del Señor Monastery “People will lie to their doctor about three things: smoking, drinking, and sex,” said Sister Alegría of the two-person Las Amigas del Señor Methodist-Quaker Monastery in Limón, Colón, Honduras. Sister Alegría is an MD herself, and she shared this wry comment during a post- Meeting Zoom discussion on November 8, when MFM celebrated the renewal of our ties with Las Amigas del Señor at the 10:00 Meeting for Worship. Sister Alegría was referring to gaining the trust of the women who come to see her at the pub- lic health clinic where she is a physician and Sister Confianza takes care of the pharmacy. Health education is as important as treating the patients’ illnesses, she explained and providing birth con- Sisters Confianza trol is part of the education for the women in the community. She added that the Catholic priest and Alegría “looks the other way,” pretending not to be aware of the birth control their clinic provides. Covenant for Caring Between MFM & Las Amigas del Señor Celebrated at Meeting for Worship on Sunday, November 8 December Newsletter Contents Earlier that morning, near the end of the 10:00 Meeting for Wor- 1 December Queries ship, Ron Marson and Sisters Alegría and Confianza read aloud in turn our shared covenants, which were made in 2009. -

Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: a Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2018 Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System Breanna Lynne Boppre Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation Boppre, Breanna Lynne, "Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System" (2018). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3220. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/13568393 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN GENDER, RACE, AND JUSTICE-INVOLVEMENT: -

On the Auto Body, Inc

FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 14, 2017 7:52:52 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of October 21 - 27, 2017 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3 ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 10/31/17 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnetts H1artnett x 5” On the Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 run DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Emma Dumont stars 15 WATER STREET in “The Gifted” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Now that their mutant abilities have been revealed, teenage siblings must go on the lam in a new episode of “The Gifted,” airing Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 Monday. ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents Massachusetts’ First Credit Union • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks St. Jean's Credit Union • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3” With 35 years experience on the North Serving over 15,000 Members •3 A Partx 3 of your Community since 1910 Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs The LawOffice of Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Auto • Homeowners 978.739.4898 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business -

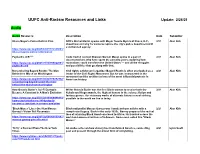

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today. -

The 2019 New York Emmy® Award Nominees 1

The 2019 New York Emmy® Award Nominees THE 62nd ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED THIS MORNING! New York, NY – Wednesday, February 20, 2019. The 62nd Annual New York Emmy® Award nominations took place this morning at the studios of CUNY-TV. Hosting the announcement was Denise Rover, President, NY NATAS. Presenting the nominees were Emmy® Award-winner Marvin Scott, Senior Correspondent and Anchor/Host, PIX News Close Up, WPIX-TV; Emmy® Award-winner Elizabeth Hashagen, Anchor, News 12 Long Island; Emmy® Award-winner Pat Battle, Anchor, WNBC-TV; and Emmy® Award-winner Virginia Huie, Reporter, News 12 Long Island. Total Number of Nominated Entries WNBC-TV 53 Queens Public Television 3 WNJU Telemundo 47 49 Spectrum News Albany 3 WPIX-TV 41 St. Lawrence University 3 MSG Networks 39 WKBW-TV 3 YES Network 33 All-Star Orchestra 2 Spectrum News NY1 31 BARD Entertainment 2 WXTV Univision 41 30 BronxNet 2 News 12 Long Island 21 IMG Original Content 2 News 12 Westchester 20 New Jersey Devils 2 NYC Life 18 Spirit Juice Studios 2 SNY 16 WGRZ-TV 2 WABC-TV 16 WHEC-TV 2 WCBS-TV 16 WIVB-TV 2 CUNY-TV 14 WNET 2 Newsday 14 WSTM-TV 2 New York Jets 12 Broadcast Design International, Inc. 1 Pegula Sports and Entertainment 11 Brooklyn Free Speech 1 WLIW21 11 CBS Interactive 1 WNYW-TV 10 DeSales Media Group 1 THIRTEEN 8 Ember Music Productions 1 BRIC TV 7 John Gore Organization 1 MagicWig Productions, Inc./WXXI 6 News 12 Brooklyn 1 NJ Advance Media 6 News 12 The Bronx 1 News 12 Connecticut 5 NHTV 1 Spectrum NY1 Noticias 5 NJTV 1 WTEN-TV 5 NVJN 1 New York Yankees 4 OGS Media Services/OASAS 1 WJLP-TV 4 Science Friday/HHMI 1 WNYT-TV 4 Sinclair Broadcast Group 1 WRGB-TV 4 Spectrum News Rochester 1 WRNN-TV & FiOS 1 News 4 Staten Island Advance/SILive.com 1 WXXI-TV 4 Theater Talk Productions 1 Blue Sky Project Films Inc. -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education Title Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968-2015 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3zq0b64q Journal Berkeley Review of Education, 9(2) Author Patterson, Ryan Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/B89242323 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Available online at http://eScholarship.org/uc/ucbgse_bre Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968–2015 Ryan Patterson William & Mary Abstract This essay explores the history of activism among students of color at the University of Oregon from 1968 to 2015. These students sought to further democratize and diversify curriculum and student services through various means of reform. Beginning in 1968 with the Black Student Union’s demands and proposals for sweeping institutional reform, which included the proposal for a School of Black Studies, this research examines how the Black Student Union created a foundation for future activism among students of color in later decades. Coalitions of affinity groups in the 1990s continued this activist work and pressured the university administration and faculty to adopt a more culturally pluralistic curriculum. This essay also includes a brief historical examination of the state of Oregon and the city of Eugene, Oregon, and their well-documented history of racism and exclusion. This brief examination provides necessary historical context and illuminates how the University of Oregon’s sparse policies regarding race reflect the state’s historic lack of diversity. Keywords: multicultural, activism, University of Oregon Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ryan Patterson. -

THE 51St ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS

THE 53RD ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED THIS MORNING! MSG Network Gets the Most Nominations with 64 New York, NY – Thursday, February 25, 2010. The 53rd Annual New York Emmy® Award nominations took place this morning at the studios of CUNY-TV. Hosting the announcement was Jacqueline Gonzalez, Executive Director, NY NATAS. Presenting the nominees were Shelly Palmer, Host of Digital Life with Shelly Palmer and President of NY NATAS; Emmy® Award-winner Marvin Scott, Senior Correspondent, PIX News at 10, and Anchor, PIX News Closeup, WPIX-TV; Emmy® Award-winner John Bathke, Reporter, News 12 New Jersey; and Emmy® Award-winner Virginia Huie, Reporter, News 12 Long Island. The New York Emmy® Awards has evolved to honor the craft of television regardless of the delivery platform. 2010 marks our third year accepting advanced media entries (original content created for broadband and portable delivery). This year all of our advanced media entries were rolled into our broadcast categories truly making this the year of recognizing outstanding achievement in television the art form not television the platform. We continue to celebrate excellence in our industry honoring the best video storytelling. Congratulations to all honored nominees! Total Number of Nominated Entries MSG Network 64 ChinaDoingBusiness.com 2 WXTV Univision 41 35 Epicurious.com 2 News 12 Connecticut 33 News 10 Now 2 WNBC-TV 32 ShellyPalmer.com 2 YES Network 27 SUAthletics.com 2 (MLB Productions for YES - 5) YESNetwork.com 2 SNY 24 Amazon.com 1 News 12 Long Island -

5.1 Docket Item: University Program Approval

HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING COMMISSION June 13, 2019 Docket Item #: 5.1 255 Capitol Street NE, Salem, OR 97310 w w w.oregon.gov/HigherEd Docket Item: University Program Approval: University of Oregon, MA in Ethnic Studies. Summary: University of Oregon proposes a new degree program leading to a MA in Ethnic Studies. The statewide Provosts’ Council has unanimously recommended approval. Higher Education Coordinating Commission (HECC) staff completed a review of the proposed program. After analysis, HECC staff recommends approval of the program as proposed. Staff Recommendation: The HECC recommends the adoption of the following resolution: RESOLVED, that the Higher Education Coordinating Commission approve the following program: MA in Ethnic Studies at University of Oregon. 255 Capitol Street NE, Salem, OR 97310 w w w.oregon.gov/HigherEd Proposal for a New Academic Program Institution: University of Oregon College/School: College of Arts and Sciences Department/Program Name: Department of Ethnic Studies (ES) Degree and Program Title: M.A. in Ethnic Studies (ES) 1. Program Description a. Proposed Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) number. 050299 b. Brief overview (1-2 paragraphs) of the proposed program, including its disciplinary foundations and connections; program objectives; programmatic focus; degree, certificate, minor, and concentrations offered. The Master of Arts degree in Ethnic Studies at the University of Oregon will be awarded to students enrolled in the Ethnic Studies Ph.D. program, which provides advanced interdisciplinary