Title the CAMPAIGN of PETITIONING for the INAUGURATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Chapter: Technical Notes

Supplementary Chapter: Technical Notes Tomoki Nakaya, Keisuke Fukui, and Kazumasa Hanaoka This supplementary provides the details of several advanced principle, tends to be statistically unstable when ei is methods and analytical procedures used for the atlas project. small. Bayesian hierarchical modelling with spatially structured random effects provides flexible inference frameworks to T1 Spatial Smoothing for Small-Area-Based obtain statistically stable and spatially smoothed estimates of Disease Mapping: BYM Model and Its the area-specific relative risk. The most popular model is the Implementation BYM model after the three authors who originally proposed it, Besag, York, and Mollié (Besag et al. 1991). The model T. Nakaya without covariates is shown as: oe|θθ~Poisson Disease mapping using small areas such as municipalities in ii ()ii this atlas often suffers from the problem of small numbers. log()θα=+vu+ In the case of mapping SMRs, small numbers of deaths in a iii spatial unit cause unstable SMRs and make it difficult to where α is a constant representing the overall risk, and vi and read meaningful geographic patterns over the map of SMRs. ui are unstructured and spatially structured random effects, To overcome this problem, spatial smoothing using statisti- respectively. The unstructured random effect is a simple cal modelling is a common practice in spatial white noise representing the geographically independent epidemiology. fluctuation of the relative risk: When we can consider the events of deaths to occur inde- vN~.0,σ 2 pendently with a small probability, it is reasonable to assume iv() the following Poisson process: The spatially structured random effect models the spatial correlation of the area-specific relative risks among neigh- oe|θθ~Poisson ii ()ii bouring areas: where oi and ei are the observed and expected numbers of wu deaths in area i, and is the relative risk of death in area i. -

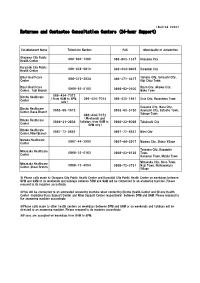

Returnee and Contactee Consultation Centers (24-Hour Support)

(April 24, 2020) Returnee and Contactee Consultation Centers (24-hour Support) Establishment Name Telephone Number FAX Municipality of Jurisdiction Okayama City Public 086-803-1360 086-803-1337 Okayama City Health Center Kurashiki City Public 086-434-9810 086-434-9805 Kurashiki City Health Center Bizen Healthcare Tamano City、Setouchi City、 086-272-3934 086-271-0317 Center Kibi Chuo Town Bizen Healthcare Bizen City、Akaiwa City、 0869-92-5180 0869-92-0100 Center, Tobi Branch Wake Town 086-434-7072 Bicchu Healthcare (From 9AM to 5PM 086-434-7024 086-425-1941 Soja City、Hayashima Town Center only) Kasaoka City、Ibara City、 Bicchu Healthcare 0865-69-1675 0865-63-5750 Asakuchi City、Satosho Town、 Center, Ikasa Branch Yakage Town 086-434-7072 (Weekends and Bihoku Healthcare 0866-21-2836holidays: from 9AM to 0866-22-8098 Takahashi City Center 5PM only) Bihoku Healthcare 0867-72-5691 0867-72-8537 Niimi City Center, Niimi Branch Maniwa Healthcare 0867-44-2990 0867-44-2917 Maniwa City、Shinjo Village Center Tsuyama City、Kagamino Mimasaka Healthcare 0868-23-0163 0868-23-6129 Town、 Center Kumenan Town、Misaki Town Mimasaka City、Shoo Town、 Mimasaka Healthcare 0868-73-4054 0868-72-3731 Nagi Town、Nishiawakura Center, Shoei Branch Village ※ Phone calls made to Okayama City Public Health Center and Kurashiki City Public Health Center on weekdays between 9PM and 9AM or on weekends and holidays between 5PM and 9AM will be connected to an answering machine. Please respond to its inquiries accordingly. ※You will be connected to an automated answering machine when contacting Bicchu Health Center and Bihoku Health Center (including Ikasa Support Center and Niimi Support Center respectively) between 5PM and 9AM. -

A Transitional Analysis on the Production of Cereals, Beans And

Journal of the Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology, Okayama University Vol.23, No.1, pp.23-48, March 2018 A Transitional Analysis on the Production of Cereals, Beans and Potatoes in Okayama Prefecture Enver Erdinç 'ø1ÇSOY*, Fumikazu ICHIMINAMI** DQG0HOWHP2NXU'ø1ÇSOY*** The contribution of cereals to economies is undoubtedly very important and has many dimensions in terms of use of cultivated areas, agricultural production, nutrition, domestic and foreign trade and national income. In this study, we ex- amined the characteristics of agricultural production in Okayama prefecture from the viewpoint of grain, beans and po- tatoes excluding rice, wheat and barley in the long term. These are undoubtedly supposed to have a certain role in comple- menting the function as the staple food of rice and wheat, etc. Also, according to our literature investigations, researchers have not focused on this context for Okayama Prefecture by not spending enough attention in the past. Therefore, we fo- cus on these subjects in this paper by examining a historical significance. It is observed that some planting area and yield of crops have drastically reduced in Okayama prefecture. Keywords: cultivated area, cereals, buckwheat, beans, potatoes, Okayama prefecture 1 INTRODUCTION 2 CEREALS OTHER THAN RICE, BARLEY AND WHEAT There are many factors that affect agriculture, including agricultural land area, quantity and quality of agricultural 2.1 Overview labor force, crops and their combinations. In this article, we There are various kinds of grains other than rice and focus only on the crops among items which have formed barley. Although these are sometimes simply referred to as agricultural land use in Okayama prefecture. -

Distribution of the Thelypteris Japonica Complex (Thelypteridaceae) in Japan

Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Ser. B, 39(2), pp. 61–85, May 22, 2013 Distribution of the Thelypteris japonica Complex (Thelypteridaceae) in Japan Atsushi Ebihara1,* and Narumi Nakato2 1 Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science, Amakubo 4–1–1, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–0005, Japan 2 Narahashi 1–363, Higashiyamato-shi, Tokyo 207–0031, Japan * E-mail: [email protected] (Received 12 February 2013; accepted 25 March 2013) Abstract The distribution of the four taxa, Thelypteris japonica forma japonica, T. japonica forma formosa, T. musashiensis and T. japonica×T. musashiensis, was reassessed by observation of spore morphology of 1984 herbarium specimens deposited in the National Museum of Nature and Science. As a result of frequent changes of identification especially between T. japonica forma formosa and T. musashiensis, the range of each taxon has been drastically updated. The hybrid was recorded in 32 prefectures in total, including newly added 25 prefectures. Key words : distribution, hybrid, spore, Thelypteris. The Thelypteris japonica complex (Thelypteri- in terms of geographical coverage. The most reli- daceae) is common understory ferns ranging able distinguishing character for the species of throughout Japan except in the Ryukyu Islands. the complex is spore morphology as demon- Japanese members of the complex were recir- strated by Nakato et al. (2004) (Fig. 2), and cumscribed by Nakato et al. (2004) based on therefore sterile specimens and/or specimens cytological and morphological characters, and with only immature spores are difficult to iden- two species, one forma and one interspecific tify. hybrid are presently accepted (Fig. 1). Nakato et al. -

Names of Shi,Machi and Mura of Major Metropolitan Areas

大都市圏構成市町村名一覧 Names of Shi ,Machi and Mura of Major Metropolitan Areas 札 幌 大 都 市 圏 Sapporo Major Metropolitan Area 中 心 市 Central City 01 北海道 Hokkaido 100 札幌市 Sapporo-shi 周 辺 市 町 村 Surrounding Area 01 北海道 Hokkaido 203 小樽市 Otaru-shi 210 岩見沢市 Iwamizawa-shi 217 江別市 Ebetsu-shi 224 千歳市 Chitose-shi 231 恵庭市 Eniwa-shi 234 北広島市 Kitahiroshima-shi 235 石狩市 Ishikari-shi 303 当別町 Tobetsu-cho 304 新篠津村 Shinshinotsu-mura 423 南幌町 Namporo-cho 428 長沼町 Naganuma-cho 仙 台 大 都 市 圏 Sendai Major Metropolitan Area 中 心 市 Central City 04 宮城県 Miyagi-ken 100 仙台市 Sendai-shi 周 辺 市 町 村 Surrounding Area 04 宮城県 Miyagi-ken 07 福島県 Fukushima-ken 202 石巻市 Ishinomaki-shi 561 新地町 Shinchi-machi 203 塩竈市 Shiogama-shi 206 白石市 Shiroishi-shi 207 名取市 Natori-shi 208 角田市 Kakuda-shi 209 多賀城市 Tagajo-shi 211 岩沼市 Iwanuma-shi 213 栗原市 Kurihara-shi 214 東松島市 Higashimatsushima-shi 215 大崎市 Osaki-shi 301 蔵王町 Zao-machi 321 大河原町 Ogawara-machi 322 村田町 Murata-machi 323 柴田町 Shibata-machi 324 川崎町 Kawasaki-machi 341 丸森町 Marumori-machi 361 亘理町 Watari-cho 362 山元町 Yamamoto-cho 401 松島町 Matsushima-machi 404 七ケ浜町 Shichigahama-machi 406 利府町 Rifu-cho 421 大和町 Taiwa-cho 422 大郷町 Osato-cho 423 富谷町 Tomiya-machi 424 大衡村 Ohira-mura 444 色麻町 Shikama-cho 445 加美町 Kami-machi 501 涌谷町 Wakuya-cho 505 美里町 Misato-machi 関 東 大 都 市 圏 Kanto Major Metropolitan Area 中 心 市 Central Cities 11 埼玉県 Saitama-ken 13 東京都 Tokyo-to 100 さいたま市 Saitama-shi 100 特別区部 Ku-area 12 千葉県 Chiba-ken 14 神奈川県 Kanagawa-ken 100 千葉市 Chiba-shi 100 横浜市 Yokohama-shi 130 川崎市 Kawasaki-shi 150 相模原市 Sagamihara-shi 周 辺 市 町 村 Surrounding Area 08 茨城県 Ibaraki-ken 209 飯能市 Hanno-shi -

An Analysis of Land-Use in Okayama Prefecture in Terms of Industrial Crops

Journal of the Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology, Okayama University Vol.23, No.1, pp.49-79, March 2018 An Analysis of Land-Use in Okayama Prefecture in terms of Industrial Crops Fumikazu ICHIMINAMI*, 0HOWHP2NXU'ø1ÇSOY** and Enver Erdinç 'ø1ÇSOY*** There are many limitations and difficulties in terms of expanding agricultural lands. Also, some other factors affect the agricultural lands that result in decreases such as climate change, erosion and misuse of the lands. It is clear that these developments in agricultural land use threaten the future of human welfare, social conditions, economic growth and food supply. In this study, we examined the land use and its significance that represent past agriculture and regional characteristics in the Chugoku region including Okayama prefecture and the Seto Inland Sea. Specifically, among the products called as industrial crops, such as cotton, pyrethrum, rush, tobacco, rapeseed, mulberry and tea, were adopted as the indicators. Currently, these landscapes can hardly be seen, only leaves of tobacco and tea can still be seen in mountainous areas. Even in agricultural land use which has almost disappeared now, it may have indirect influence as in the case of reclaimed land and rush products. Therefore, we reaffirmed in this study the reasons for their existence and their significance. Keywords: industrial crop, cultivated area, rural geography, agriculture, Okayama prefecture 1 INTRODUCTION tion not only to the temporal change of the indicator but also the spatial difference. Agriculture is a strategic sector for countries as well as In this research, we restrict the area of Okayama human being in the aspects of basic food supply, raw prefecture and deal with crops other than cereals, vegetables, materials for the industry, and employment. -

Tourism Inventory of Okayama Prefecture: an Analysis on Main Sightseeing Spots in Terms of the Number of Tourists

Journal of the Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology, Okayama University Vol.22, No.1, pp.1-28, March 2017 Tourism Inventory of Okayama Prefecture: An Analysis on Main Sightseeing Spots in terms of the Number of Tourists Fumikazu ICHIMINAMI*, Meltem Okur 'ø1d62< DQG(QYHU Erdinç 'ø1d62< At the early stage of this paper, Okayama prefecture was analyzed by the author focusing on the tendency of main sightseeing-areas based on the number of tourists for three decades (Ichiminami, 2002). In this study, the main sightseeing spots in Okayama pref. are also examined and the developments are explained in a more detailed and updated perspective by extending over current features and the number of tourists. One of the important reasons in a significant increase in tourists in Okayama is the opening of the highways, the bullet train and cross-linking of the Seto Ohashi Bridge. At the same time, there are some waves in the increase or decrease of the tourist trends appearing from several vital developments such as environmental, climatic, social, economic and spatial. In this regard, research objectives of the study are mainly based on investigating and making a comprehensive study on main sightseeing spots in Okayama pref. to find new tourism values and to provide a tourism inventory of Okayama pref. by means of information, data and clues from the field in/between the tourist destinations such as hotel guests, gardens and castles. Therefore, Okayama pref. has a rich potential of historical and cultural heritage in terms of spatial planning and growth. The important point is that the structural adaptation between historical and cultural assets and the city life should be provided and protected for domestic and foreign tourism as much as creating better futures in health tourism, gastronomy tourism, cultural tourism, belief tourism, congress tourism, thematic tourism and local tourism. -

Space Traveling Seeds: Sunflower Seeds Stayed in Space Were Delivered to Schoolchildren

Vol. 5, December 2013 News Space traveling seeds: sunflower seeds stayed in space were delivered to schoolchildren Associate Professor Manabu Sugimoto, Institute of Plant Science and Resources, who is the Japanese coordinator of the Russian international space educational experiment 'Bion-M1', delivered space traveling sunflower seeds to Oshima Junior High School of Kasaoka City. In the experiment, the sunflower seeds prepared by elementary and junior high school students of Kasaoka and Asakuchi Cities were loaded into the Associate Professor Manabu Sugimoto showing students 'space Russian unmanned biosatellite Bion-M1, which traveling seeds'. was launched into orbit and returned to Earth after spending 30-days in space. The students will cultivate the 'space traveling seeds' and observe the effect of the space environment on the survival and growth of the seeds. Sugimoto gave a lecture to the students of Oshima Junior High School about the goals of the experiment and the significance of plant scientific research in space. Then the students received unopened packages, each containing about 70 sunflower seeds that returned from space, and planted the seeds into The packages of sunflower seeds prepared by Oshima JHS, Chuo pots and watered them immediately. ES, and Yorishima ES (from left to right). Other schools participating in this experiment are Chuo Elementary School of Kasaoka City and Yorishima Elementary School of Asakuchi City. Bion-M1 biosatellite launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on 19 April 2013 and returned to Earth on 19 May 2013. 1-1-1 Tsushima-naka, Kita-ku, Okayama 700-8530 Japan © Okayama University. -

Okayama Prefecture

Okayama Prefecture Kaaz Corporation (Okayama City) Manufacture of gear box for grass mowers based high-precision low-cost processing and powder metallurgy technologies Nakashima Propeller Co., Ltd. (Okayama City) World-leading ship propeller manufacturer Takaya Corporation (Ibara City) Enjoys the top market share in the world in printed-wiring board testing systems Meidai Corporation (Kurashiki City) First commercialization of Tetra-axial® weaving machine “Tetras®” in the world Syoei Co., Ltd. (Mimasaka City) Holds 60% global market share in cams for ship engines Yasda Precision Tools K.K. (Asakuchi Gun) World-leading ultra-precision machining center 299 the world’s top market share of 40%. the world’s new materials and a new production process.new technology, The company has secured used in grass mowers and realizedcost reduction and high-quality products by adopting Thecompany has refurbished its manufacturing and assembling method for gear boxes overseas in markets. also in Japan only but not are received allThey well olive trees. shaking transmission), a blower that collects fallen leaves by utilizing wind blasts, and a drops that shaker olive berries by less step (hydraulic HST with mounted mower lawn self-propelled ahigh-value-added including name, than 100kindsproducts of More 40%. of share market largest world’s the captured has product The abroad. competitors its to mowers, grass of overseas markets boundfor are 80% products the of laborsaving. of achievement and processes on production cutback drastic a in resulting company, a specialized with cooperation in machining without be can molded that parts casting precision and gears metallurgical powder developed grass mowersare withoutpeer in their lightness in weight, low vibration, and low noise. -

The Time for the Annual Medical Check-Up Has Arrived. Check How to Do Yours Here! Taking the Exam Is Easy

Medical Checkup 2020 The time for the annual medical check-up has arrived. Check how to do yours here! Taking the exam is easy Just follow these 3 steps Step 1 1 See the list of hospitals starting on page 10 Step 2 2 Call the desired hospital and schedule the exam according to your age (Check on page 4) Step 3 3 Access the link and tell us about your exam information Go on the schedule date and Done! take your exam (don't forget to take your hoken-sho) 3 Your age by April 1, 2021 For 34 years old and below Houtei Kenshin - 法定健診 "Houtei Kenshin wo yoyaku shitai desu" -34 Paid by Techno Service For 35 years old and up Ippan Kenshin - ⼀般健診 "Ippan Kenshin wo yoyaku shitai desu" +35 Paid by Techno Service If you want to do more exams... If you're exactly 40 or 50 years old by April 1st, 2021 Fuka Kenshin - 付加健診 Optional paid exam for people 40 OR 50 either 40 or 50 years old Years old Not Paid by Techno Service More details on page 9 4 Important points The exam must be scheduled according to your age, to find out which exam to schedule, check out p. 4 The exam must be done until 28/02/2021. Exams after that date will not be accepted or paid. The exam must be carried out within the period of the employment contract. Techno Service will not pay for exams outside the employment contract. 5 Confirming the exam After booking, declare and confirm your exam DECLARE HERE Minimum deadline for declaration of 2 weeks before the exam (deadline). -

The 16 Asian Pacific Telephone Counseling Conference Building a Bridge Between Hearts -In an Isolated Society

th The 16 Asian Pacific Telephone Counseling Conference The 36th Federation of Inochi-no-Denwa (FIND) National Conference in Okayama Building a bridge between hearts -In an isolated Society Contents Greeting from Director of FIND‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥2 Conference Schedule ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥3 The 1st Day Opening Ceremony / Keynote Speech / Activities Reports / Banquet ‥‥‥4 The 2nd Day Study Groups / Workshops / Representatives Meeting / Exchange Meeting‥6 The 3rd Day Symposium (Open to the Public) ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥26 English Lecture / Closing Ceremony‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥29 Venues Guide ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥Pending 1 Welcome Greeting Let’s build a bridge between hearts in “the sunny country Okayama” Director of Federation of Inochi No Denwa (telephone counseling) Chair of Forum of Okayama Inochi No Denwa Administration Director of Zikei Hospital HORII Shigeo Ph.D. The 36th Annual Federation of Inochi-no-Denwa National Conference in Okayama and the 16th Triennial Asian-Pacific Telephone Counseling Conference, “Building a Bridge between Hearts” will be held at the Okayama Plaza Hotel and the Okayama International Center, from Thursday, October 24 to Saturday, October 26, 2019. Telephone counseling, “Inochi-no-Denwa” in Japanese started in 1971. The Japanese Federation of Inochi-no-Denwa (FIND) was established in 1977. Since then, it has been continuous operation for 40 years. Now more than 6,300 telephone counseling volunteers at 50 centers located all over the country (including the Miyazaki Center opening this September) handle about 650 thousand calls a year (2018), engaging in listening to lonely, isolated voices. The 36th National Conference for those volunteers will be held in conjunction with the 16th triennial conference of the Asian-Pacific Telephone Counseling, in Okayama where the Okayama Center is celebrating its 35th anniversary. -

Mega-Solar Photovoltaic Power Plant Construction Results

Experience of Solar Power Plant We have experience more than 1 GW in Japan. One of the Leading Company in Japan for Solar Power Plant (※) Project of completion construction : 96 Projects Project of under construction : 9 Projects As of MAY 2021 Completion Construction :About 881MW Under Construction :About 298MW (※)An in-company investigation Experience List of Solar Power Plant As of MAY 2021 Project of completion construction Hokkaido Yufutsu, Hokkaido 111.0 Chubu Komaki,Aichi 0.5 Chugoku Tamano, Okayama 2.2 Yufutsu, Hokkaido 13.5 Region Chita, Aichi 1.0 Region Tamano, Okayama 17.3 Kamiiso, Hokkaido 24.0 Chita, Aichi 1.6 Niimi, Okayama 1.1 Noboribetsu, Hokkaido 18.0 Chita, Aichi 1.0 Asakuchi, Okayama 2.5 Tohoku Hachinohe, Aomori 14.8 Tahara, Aichi 80.9 Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima 2.2 Region Isawa, Iwate 1.9 Tahara, Aichi 6.4 Takehara, Hiroshima 1.9 Isawa, Iwate 1.3 Nakatsugawa, Gifu 1.0 Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi 2.4 Ichinoseki, Iwate 1.1 Kikugawa, Shizuoka 2.2 Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi 2.4 Ichinoseki, Iwate 2.5 Kosai, Shizuoka 1.6 Nagato, Yamaguchi 2.3 Kesennuma, Miyagi 1.0 Kinki Takaoka, Toyama 1.9 Hofu, Yamaguchi 1.9 Sendai, Miyagi 1.8 Region Toyama, Toyama 6.0 Ube, Yamaguchi 1.5 Shibata, Miyagi 2.5 Iga, Mie 1.2 Ube, Yamaguchi 1.1 Ishinomaki, Miyagi 1.3 Iga, Mie 2.0 Izumo, Shimane 1.3 Ishinomaki, Miyagi 14.0 Kuwana, Mie 3.6 Shikoku Kami, Kochi 1.1 Watari, Miyagi 1.7 Yokkaichi, Mie 2.5 Rigion Komatsujima, Tokushima 21.2 Osaki,Miyagi 1.8 Yokkaichi, Mie 1.8 Komatsujima, Tokushima 12.8 Fukishima, Fukushima 2.2 Shima, Mie 2.1 Kyushu Iizuka, Fukuoka 2.0