An Analysis of Web Coverage on the 2018 West Japan Heavy Rain Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recovering from Heavy Rain Damage Through Cooperation and Think-And

Our Starting Point Our Starting Point Strategy of Value Creation for Our Vision A Foundation Supporting Value Creation Data Status of operations and damage directly after the Heavy Rain Event of July 2018 Situation at 2:00pm, July 11, 2018 Recovering from heavy rain Operational Operations suspended Shinji Tottori Yonago Higashi- Kisuki Line Maizuru damage through cooperation San-in Line Nishi-Maizuru Izumo-Yokota Chizu Mochigase Kamiiwami Fukuchiyama ru Wadayama Hakubi Line Niimi Tsuyama Express Chizu Maizu Line Bingo-Ochiai Imbi Teramae Masuda Line Ayabe Higashi- San-in Line Hiroshima Bichu- Shiomachi Okayama ama Hagi Shin-Iwakuni Kojiro Tsuy Line Tokuyama ntan Line Aki- Kozuki Sayo Ba and think-and-act initiatives ine akubi Line Kameyama Fuchu H Geibi Line Higashi- Kishin Fukuen Line Line San-yō L Kannnabe Okayama Kamigori Kabe Soja Line Higashihiroshima Himeji Mihara Fukuyama The Heavy Rain Event of July 2018 resulted in large-scale damage throughout West Japan, including in areas where Shin-Yamaguchi Kaitaichi Kushigahama Yokogawa Kasaoka Gantoku Line JR-West operates, and many sections of track were rendered unusable. Iwakuni Kurashiki Kure Line Yanai Amid this unprecedented damage, we came together as a Group and by implementing many think-and-act initiatives and San-yō Line cooperating with local stakeholders, we were able to recover many damaged sections of track and restart operations.* Recovery work In order to get life back to normal as soon as possible, we mobilized Opening land around the capabilities of the entire Group and cooperated with affiliates An entire stations for and local stakeholders in various areas to advance recovery efforts. -

Supplementary Chapter: Technical Notes

Supplementary Chapter: Technical Notes Tomoki Nakaya, Keisuke Fukui, and Kazumasa Hanaoka This supplementary provides the details of several advanced principle, tends to be statistically unstable when ei is methods and analytical procedures used for the atlas project. small. Bayesian hierarchical modelling with spatially structured random effects provides flexible inference frameworks to T1 Spatial Smoothing for Small-Area-Based obtain statistically stable and spatially smoothed estimates of Disease Mapping: BYM Model and Its the area-specific relative risk. The most popular model is the Implementation BYM model after the three authors who originally proposed it, Besag, York, and Mollié (Besag et al. 1991). The model T. Nakaya without covariates is shown as: oe|θθ~Poisson Disease mapping using small areas such as municipalities in ii ()ii this atlas often suffers from the problem of small numbers. log()θα=+vu+ In the case of mapping SMRs, small numbers of deaths in a iii spatial unit cause unstable SMRs and make it difficult to where α is a constant representing the overall risk, and vi and read meaningful geographic patterns over the map of SMRs. ui are unstructured and spatially structured random effects, To overcome this problem, spatial smoothing using statisti- respectively. The unstructured random effect is a simple cal modelling is a common practice in spatial white noise representing the geographically independent epidemiology. fluctuation of the relative risk: When we can consider the events of deaths to occur inde- vN~.0,σ 2 pendently with a small probability, it is reasonable to assume iv() the following Poisson process: The spatially structured random effect models the spatial correlation of the area-specific relative risks among neigh- oe|θθ~Poisson ii ()ii bouring areas: where oi and ei are the observed and expected numbers of wu deaths in area i, and is the relative risk of death in area i. -

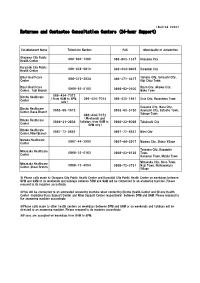

Returnee and Contactee Consultation Centers (24-Hour Support)

(April 24, 2020) Returnee and Contactee Consultation Centers (24-hour Support) Establishment Name Telephone Number FAX Municipality of Jurisdiction Okayama City Public 086-803-1360 086-803-1337 Okayama City Health Center Kurashiki City Public 086-434-9810 086-434-9805 Kurashiki City Health Center Bizen Healthcare Tamano City、Setouchi City、 086-272-3934 086-271-0317 Center Kibi Chuo Town Bizen Healthcare Bizen City、Akaiwa City、 0869-92-5180 0869-92-0100 Center, Tobi Branch Wake Town 086-434-7072 Bicchu Healthcare (From 9AM to 5PM 086-434-7024 086-425-1941 Soja City、Hayashima Town Center only) Kasaoka City、Ibara City、 Bicchu Healthcare 0865-69-1675 0865-63-5750 Asakuchi City、Satosho Town、 Center, Ikasa Branch Yakage Town 086-434-7072 (Weekends and Bihoku Healthcare 0866-21-2836holidays: from 9AM to 0866-22-8098 Takahashi City Center 5PM only) Bihoku Healthcare 0867-72-5691 0867-72-8537 Niimi City Center, Niimi Branch Maniwa Healthcare 0867-44-2990 0867-44-2917 Maniwa City、Shinjo Village Center Tsuyama City、Kagamino Mimasaka Healthcare 0868-23-0163 0868-23-6129 Town、 Center Kumenan Town、Misaki Town Mimasaka City、Shoo Town、 Mimasaka Healthcare 0868-73-4054 0868-72-3731 Nagi Town、Nishiawakura Center, Shoei Branch Village ※ Phone calls made to Okayama City Public Health Center and Kurashiki City Public Health Center on weekdays between 9PM and 9AM or on weekends and holidays between 5PM and 9AM will be connected to an answering machine. Please respond to its inquiries accordingly. ※You will be connected to an automated answering machine when contacting Bicchu Health Center and Bihoku Health Center (including Ikasa Support Center and Niimi Support Center respectively) between 5PM and 9AM. -

Title the CAMPAIGN of PETITIONING for the INAUGURATION

THE CAMPAIGN OF PETITIONING FOR THE INAUGURATION OF A NATIONAL DIET-THE Title PROCESS OF THE ORGANIZATION OF THE SANYO LIBERAL PARTY- Author(s) Naito, Seichu Citation Kyoto University Economic Review (1957), 27(1): 32-52 Issue Date 1957-04 URL https://doi.org/10.11179/ker1926.27.32 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University VOLUME XXVII NUMBER 1 Kyoto University Economic Review MEMOIRS OF THE FACULTY OF ECONOMICS IN THE KYOTO UNIVERSITY THE ECONOMIC THEORY CONCIEVED BY MAX WEBER YU"zo DEGUCHI I TECHNICAL COMPLEMENTARITY IN LINEAR PROGRAMMING Tadashi IMAGAWA 14 THE CAMPAIGN OF PETITIONING FOR THE INAUGURATION OF A NATIONAL DIET Seichii. NAITO 32 ON THE COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES OF THE MONGOLS IN THE EARLY YEARS OF YUAN DYNASTY Koichi ITO 53 APRIL. 1957 PUBLISHED BY THE F ACUL TY OF ECONOMICS KYOTO UNIVERSITY • KYOTO, JAPAN THE CAMPAIGN OF PETITIONING FOR THE INAUGURATION OF A NATIONAL DIET -THE PROCESS OF THE ORGANIZATION OF THE SANYO LIBERAL PARTY- By SeichU NAITO* .FOREWORD The year 1880 saw the upsurging clamor for liberty and popular rights being consolidated into a nationwide movement for demanding a speedy inauguration of a National Diet at the same time that various layers of the nation continued to have their respective class interests promoted. This was highly significant in the historical process of the Japanese nation in that it marked the first instance of a nationally organized resistance against the contemporary ruling authority. As the prevailing clamor for liberty and popular rights was organized into a vast movement on a national scale embracing all classes of the people, it marked· a significant development for it was intrinsically distinguishable from the sporadic farmers' rebellious uprisings which were often recorded during the ancien regime, and, seen in this light, the movement for liberty and popular rights would well be de fined as a democratic revolutionary movement. -

Molluscan Fauna of The“ Miocene” Namigata Formation in the Namigata Area, Okayama Prefecture, Southwest Japan

Jour. Geol. Soc. Japan, Vol. 119, No. 4, p. 249–266, April 2013 JOI: DN/JST.JSTAGE/geosoc/2012.0048 doi: 10.5575/geosoc.2012.0048 Molluscan fauna of the“ Miocene” Namigata Formation in the Namigata area, Okayama Prefecture, southwest Japan Abstract Takashi Matsubara The molluscan fauna of the Namigata Formation, traditionally ac- cepted to be of Miocene age, are reexamined taxonomically, and the Received 27 February, 2012 geologic age of the formation and its paleogeographic implications Accepted 12 June, 2012 are discussed. The formation is subdivided into the main part and two new members (the Senjuin Shell-Sandstone and Ônishi Con- Division of Natural History, Museum of Na- glomerate members). The Namigata Formation yielded 13 species of ture and Human Activities Hyogo, 6 Yayoiga- Gastropoda, 16 species of Bivalvia and 1 species of Scaphopoda. The oka, Sanda 669-1546, Japan occurrences of Molopophorus watanabei Otuka, Acila (Truncacila) nagaoi Oyama and Mizuno, Chlamys (Nomurachlamys?) namiga- Corresponding author: T. Matsubara, [email protected] taensis (Ozaki), and Isognomon (Hippochaeta) hataii Noda and Fu- ruichi indicate that the molluscan age should be revised to the late Late Eocene–Early Oligocene. Taking account of the latest elasmo- branch data and preliminary strontium isotope ratio, the age of the formation is confined to the late Late Eocene. The present and recent results show that the First Seto Inland Sea was actually composed of two sea areas that existed at different times: the Paleogene sea area is estimated to have been an open sea facing south to the Pacific Ocean, whereas that in the Miocene is thought to have been an em- bayment connected to the northwest to the Sea of Japan. -

The O. Maculatus Species Group (Coleoptera: Elmidae) 197-238 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Koleopterologische Rundschau Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 85_2015 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kamite Yuuki Artikel/Article: Revision of the genus Optioservus SANDERSON, 1953, part 2: The O. maculatus species group (Coleoptera: Elmidae) 197-238 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Koleopterologische Rundschau 85 197–238 Wien, September 2015 Revision of the genus Optioservus SANDERSON, 1953, part 2: The O. maculatus species group (Coleoptera: Elmidae) Y. KAMITE Abstract The Optioservus maculatus species group (Coleoptera: Elmidae) is newly proposed. Ten species, including six new species, are recognized: O. gapyeongensis JUNG, KAMITE & BAE, O. hagai NOMURA, O. inahatai sp.n., O. maculatus NOMURA, O. masakazui sp.n., O. occidens sp.n., O. ogatai sp.n., O. sakaii sp.n., O. variabilis NOMURA and O. yoshitomii sp.n. Larvae of nine species are also described: O. gapyeongensis JUNG, KAMITE & BAE, O. hagai NOMURA, O. maculatus NOMURA, O. masakazui sp.n., O. occidens sp.n., O. ogatai sp.n., O. sakaii sp.n., O. variabilis NOMURA and O. yoshitomii sp.n. Key words: Coleoptera, Elmidae, Optioservus, Optioservus maculatus species group, taxonomy, larvae. Introduction The Nearctic Optioservus fastiditus and O. quadrimaculatus species groups have already been revised by KAMITE (2013). The O. fastiditus species group includes six East Nearctic species and the O. quadrimaculatus species group includes seven West Nearctic species. At present, a total of six species of Optioservus SANDERSON, 1953 are known from the Palearctic Region: O. hagai NOMURA, 1958, O. maculatus NOMURA, 1958, O. nitidus NOMURA, 1958, O. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

Taxonomic Revision of the Longiscapus-Group of Arcuphantes

Acta arachnol., 44 (2) : 129-152, December 30, 1995 Taxonomic Revision of the longiscapus-group of Arcuphantes (Araneae: Linyphiidae) in Western Japan, with a Note on the Concurrent Diversification of Copulatory Organs between Males and Females Yoh IHARA 1 井 原 庸1):西 日本 の ナ ガ エヤ ミサ ラグモ種 群 の分類 学的 改訂 お よび雌雄 の交尾 器 官の協 同的 多様 化 Abstract The longiscapus group in the genus Arcuphantes (Linyphiidae) is revised based on genital morphology and geographic distributional pattern. This group should be treated as a closely related species group or a single superspecies by their morphology and distribution. Three known species, A, longiscapus, A. hibanus and A. iharai, and five new species, A. saitoi, A. setouchi, A. tsurusakii, A. nojimai and A. okiensis are described. These eight species are only distributed in western Honshu, northeastern Shikoku and some adjacent islands, Japan. It gives para- patric pattern to the distribution except for some cases of narrow overlap. Mor- phological correspondence between male palp and epigynum was found as a species- specific character. Twenty species of the genus Arcuphantes (Linyphiidae) have been described from various areas of Japan. However, their taxonomy is still far from complete, and there are many undescribed species even in the main islands of Japan. What makes the taxonomy more complicated is the remarkable geographic differentiation in their copulatory organs exhibited by the species of the genus. In this paper, I deal with eight species of the genus Arcuphantes (longiscapus, hibanus, iharai and five new species), which are closely related to each other, from western Honshu, Shikoku and some adjacent islands, Japan. -

Educational Institution Kake Educational Institution | 2 | Experience Japanese History and Culture the Cities of OKAYAMA & KURASHIKI

● Okayama University of Science 1-1 Ridai-cho, Kita-ku, Okayama City, Okayama, JAPAN URL: https://www.ous.ac.jp/ KAKE ● Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts 2640 Nishiura, Tsurajima-cho, Kurashiki-city, Okayama, JAPAN EDUCATIONAL URL: https://www.kusa.ac.jp/ INSTITUTION ● Chiba Institute of Science 3 Shiomi-cho, Choshi-city, Ciba, JAPAN URL: http://www.cis.ac.jp/ ● Tamano Institute of Health and Human Services 1-1-20 Chikkou, Tamano-city, Okayama, JAPAN URL: http://www.tamasen.ac.jp/ ● Okayama University of Science Specialized Training College 8-3 Handa-cho, Kita-ku, Okayama-city, Okayama, JAPAN URL: https://www.risen.ac.jp/ ● Okayama University of Science High School 1-1 Ridai-cho, Kita-ku, Okayama City, Okayama, JAPAN ● ● ● URL: http://www.ridaifu.net/ Chiba Institute of Science ● Okayama University of Science Junior High School 1-1 Ridai-cho, Kita-ku, Okayama City, Okayama, JAPAN Okayama University of Science URL: http://www.kake.ac.jp/~info-j/ Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts ● Mikage International Kindergarten 2-15-27 Mikage, Higashinada-ku, Kobe-city, Hyogo, JAPAN URL: http://www.kakemik.jp/ (2020) Founding Philosophy Locations ● Okayama University of Science ● Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts ● Chiba Institute of Science ● Tamano Institute of Health and Human Services ● Okayama University of Science Specialized Training College ● Okayama University of Science High School ● Okayama University of Science Junior High School ● Mikage International Kindergarten 岡山理科大学 岡山理科大学 附属中学校 附属高等学校 Okayama University of Science Jr. High School Okayama University of Science High School Okayama University of Science Chiba Institute of Science To draw out each and every youth’s abilities to their maximum potential, and to educate individuals to 岡山理科大学専門学校 contribute to society as skilled professionals and as Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts Okayama University of Science Specialized Training College members of their communities. -

RJCPN Prayer Bulletin 3

1 RJCPN PRAYER BULLETIN # 3 (Fall, 2011) FOR 47 RJCPN FOREIGN PREFECTURAL PRAYER GROUPS Instructions for the FPPG Prayer Group Leader: Please have your prayer group first focus its prayer on the unchurched rural areas (URAs) of the one of 47 specific prefecture in Japan’s 9 regions that your group has adopted. Prayer requestss are located in the box at the end of the page for your prefecture. If you have extra time, feel free to also pray for the broader region in which your prefecture is located and/or for the general rural Japan-wide prayer items on page 2. Please pray at least monthly, though prayer bulletins for now are quarterly or less. This edition of the bulletin also includes maps of the regions and for the URAs within many of the prefectures, as well as statistical information on the state of the church in each region. If you print this out, please remember to first select just the 1-3 pages relevant to your group (as the whole thing is 57 pages!). A Table of Contents is provided to help you easily find the section relevant to your adopted prefecture. ***PLEASE SKIP DOWN TO YOUR REGION AND THEN FIND THE PRAYER REQUEST BOX WITHIN THAT FOR YOUR SPECIFIC PREFECTURE*** Table of Contents 1) Map of Regions and Prefectures in Japan Page 2 (see where in Japan your adopted prefecture is). 2) Rural Japan-wide General Prayer Requests (optional section). Page 3. 3) Hokkaido Region and Prefecture. Page 4. b) Mie Prefecture 4) Tohoku Region Pages 5-11 c) Shiga Prefecture a) Regional Information d) Kyoto Prefecture b) Aomori Prefecture e) Osaka Prefecture c) Iwate Prefecture f) Hyogo Prefecture d) Miyagi Prefecture g) Nara Prefecture e) Akita Prefecture h) Wakayama Prefecture f) Yamagata Prefecture 8) Chuugoku Region. -

OKAYAMA, KURASHIKI and SETO-OHASHI BRIDGE PAGE 1/ 5

OKAYAMA, KURASHIKI and SETO-OHASHI BRIDGE PAGE 1/ 5 PG-602 OKAYAMA, KURASHIKI and SETO-OHASHI BRIDGE Okayama (岡山) is one of the major commercial, industrial and Kurashiki (倉敷) is an old merchants town near Okayama. In cultural cities in the Chugoku District in western Japan. It is feudal days, it thrived as a port for the shipment of rice; several nationally known for its celebrated Korakuen Garden. It also old rice granaries remain there. Its olden time atmosphere and a serves as a main gateway to Inland Sea National Park and variety of museums lure many visitors to Kurashiki. Shikoku Island. Okayama Airport Bizen- Shin- Soja Ichinomiya bus Kurashiki JR Kibi Line Aioi Kibitsu Okayama JR Shinkansen Line To Hiroshima JR Sanyo Line To Himeji, Kyoto Kurashiki Higashi- bus Okayama Imbe Ako Line Kojima Washuzan Hill Uno bus To Shikoku Is. Access: By Air from Tokyo (Haneda Airport) To Operated by Time required Daily Flights One-way fare Access airport – downtown 35 min. to Okayama Sta. by bus (¥680) ANA 45 min. to Kurashiki Sta. by Airport Okayama Toll free: 0120-029- 1 hr. 20 min. 5 ¥25,500 - ¥27,500 Limousine bus (¥1,000) 222 *Only 4 bus services per day. Please confirm the time table. By Train *Number of flights and fare may change by season. To From Type of Transportation Time required Daily runs One-way fare Okayama Tokyo JR Shinkansen (By Hikari) 3 hrs. 53 min. - 4 hrs. 10 min. 32 ¥16,360 JR Shinkansen (By Nozomi) 3 hrs. 12 min. - 3 hrs. 18 min. -

The Vegetation on the Granite Rock Area at Ashimori, Okayama City, S.W

Naturalistae 16: 19-27(Feb. 2012) © 2012 by Okayama University of Science, PDF downloadable at http://www.ous.ac.jp/garden/ Original paper The vegetation on the granite rock area at Ashimori, Okayama City, S.W. Honshu, Japan 1 2 Ken OHTA & Yoshio HADA 岡山市足守における花崗岩地域の植生 太田 謙 1・波田善夫 2 Abstract: The vegetation developed on the granite rock area was studied phytosociologically at Ashi- mori, Okayama City, S.W. Honshu, Japan. We recognized 12 communities of forest vegetation and three communities of moor vegetation. The typical Pinus densiflora community, covering 70% of the study area, was developed mainly on the ridges and slopes. We described the floristic composition of each communities, and drew a detailed vegetation map based on the recognized floristic communities in accord with the microtopographic data obtained through the field survey. I. Introduction III. Methods To reveal the influence of geological and topo- Field surveys were carried out in 2005-2007. graphical feature on the vegetation, we investi- Cover-abundance and sociability (Braun-Blan- gated the vegetation of the granite rock area of quet 1964) of all vascular plants were recorded Ashimori, Okayama City, S.W. Honshu, Japan. in 73 quadrats (size 100-225 m2) in the forests. Study of the vegetation developed on granite rock The names of species followed Satake et al. area in Okayama Pref. were carried by Ishibashi (1981, 1982a, 1982b, 1989a, 1989b) for flower- (1980), and Nishimoto and Hada (1994). But ing plants, and Iwatsuki (1992) for ferns. these report has no vegetation map. To elucidate Vegetation types were classified on the basis the relation between vegetation and geological of species composition by phytosociological and topographical feature, we needs an accurate methods (Braun-Blanquet 1964).