Multiple Dimensions of Impermanence in Dogen's "Genjokoan"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REVIEW ARTICLE Truth and Method in Dogen Scholarship

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE REVIEW ARTICLE Truth and Method in Dogen Scholarship A Review of Recent Works Steven Heine Translations Thomas Cleary, trans. ShObOgenzO: Zen Essays by DOgen. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1986. Pp. 123. Hee-J in Kim, trans. Flowers of Emptiness: Selections from DOgen’s ShGbOgenzb. Lewiston/Queenston; The Edward Mellon Press, 1985. Pp. xviii + 346. Nishiyama KOsen, and John Stevens, trans. DOgen Zenji’s ShbbbgenzO {The Eye and Treasury of the True Law). Sendai, Japan: Daihokkaikaku, 1975-1983. 4 vols. Tanahashi Kazuaki, ed. Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master DOgen. San Fran cisco: North Point Press, 1985. Pp. xii + 356. Yokoi Yuho, trans. The ShbbO-genzO. Tokyo: Sankibo Buddhist Bookstore, 1986. Pp. 876. Commentaries William R. LaFleur, ed. DOgen Studies. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press (The Kuroda Institute, Studies in East Asian Buddhism, No. 2), 1985. Pp. 185. I. Introduction: The Relation between Truth and Method The publication over the past few years of several new Ddgen transla tions and commentaries highlights the increasing intensification and specialization in English-language studies of the field. The translations now make available two complete versions of the ShObOgenzO as well as numerous renderings reflecting different approaches and emphases of almost all of the most philosophically important fascicles. An assess ment of these can indicate how much progress has been made toward a 128 TRUTH AND METHOD IN DOGEN SCHOLARSHIP “definitive” (thorough and accurate) English edition of DOgen’s masterwork in addition to the obstacles that remain in reaching that goal. -

Print This Article

Journal of Global Buddhism Vol. 18 (2017): 112–128 Special Focus: Buddhists and the Making of Modern Chinese Societies Buddhism and Global Secularisms David L. McMahan, Franklin and Marshall College Abstract: Buddhism in the modern world offers an example of (1) the porousness of the boundary between the secular and religious; (2) the diversity, fluidity, and constructedness of the very categories of religious and secular, since they appear in different ways among different Buddhist cultures in divergent national contexts; and (3) the way these categories nevertheless have very real-world effects and become drivers of substantial change in belief and practice. Drawing on a few examples of Buddhism in various geographical and political settings, I hope to take a few modest steps toward illuminating some broad contours of the interlacing of secularism and Buddhism. In doing so, I am synthesizing some of my own and a few others’ research on modern Buddhism, integrating it with some current research I am doing on meditation, and considering its implications for thinking about secularism. This, I hope, will provide a background against which we can consider more closely some particular features of Buddhism in the Chinese cultural world, about which I will offer some preliminary thoughts. Keywords: secularism; modern Buddhism; meditation; mindfulness; vipassanā The Religious-Secular Binary he wave of scholarship on secularism that has arisen in recent decades paints a more nuanced picture than the reigning model throughout most of the twentieth century. For most of the twentieth century, social theorists adhered Tto a linear narrative of secularism as a global process of religion waning and becoming less relevant to public life. -

Mindfulness and the Buddha's Noble Eightfold Path

Chapter 3 Mindfulness and the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path Malcolm Huxter 3.1 Introduction In the late 1970s, Kabat-Zinn, an immunologist, was on a Buddhist meditation retreat practicing mindfulness meditation. Inspired by the personal benefits, he de- veloped a strong intention to share these skills with those who would not normally attend retreats or wish to practice meditation. Kabat-Zinn developed and began con- ducting mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in 1979. He defined mindful- ness as, “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment to moment” (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145). Since the establishment of MBSR, thousands of individuals have reduced psychological and physical suffering by attending these programs (see www.unmassmed.edu/cfm/mbsr/). Furthermore, the research into and popularity of mindfulness and mindfulness-based programs in medical and psychological settings has grown exponentially (Kabat-Zinn 2009). Kabat-Zinn (1990) deliberately detached the language and practice of mind- fulness from its Buddhist origins so that it would be more readily acceptable in Western health settings (Kabat-Zinn 1990). Despite a lack of consensus about the finer details (Singh et al. 2008), Kabat-Zinn’s operational definition of mindfulness remains possibly the most referred to in the field. Dozens of empirically validated mindfulness-based programs have emerged in the past three decades. However, the most acknowledged approaches include: MBSR (Kabat-Zinn 1990), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al. -

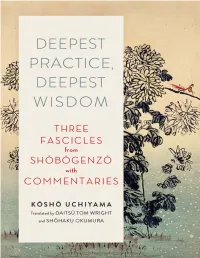

Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

“A magnificent gift for anyone interested in the deep, clear waters of Zen—its great foundational master coupled with one of its finest modern voices.” —JISHO WARNER, former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association FAMOUSLY INSIGHTFUL AND FAMOUSLY COMPLEX, Eihei Dōgen’s writings have been studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. In Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom, Kshō Uchiyama, beloved twentieth-century Zen teacher, addresses himself head-on to unpacking Dōgen’s wisdom from three fascicles (or chapters) of his monumental Shōbōgenzō for a modern audience. The fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include “Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece. At turns poetic and funny, always insightful, this is Zen wisdom for the ages. KŌSHŌ UCHIYAMA was a preeminent Japanese Zen master instrumental in bringing Zen to America. The author of over twenty books, including Opening the Hand of Thought and The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo, he died in 1998. Contents Introduction by Tom Wright Part I. Practicing Deepest Wisdom 1. Maka Hannya Haramitsu 2. Commentary on “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” Part II. Refraining from Evil 3. Shoaku Makusa 4. Commentary on “Shoaku Makusa” Part III. Living Time 5. Uji 6. Commentary on “Uji” Part IV. Comments by the Translators 7. Connecting “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” to the Pāli Canon by Shōhaku Okumura 8. Looking into Good and Evil in “Shoaku Makusa” by Daitsū Tom Wright 9. -

Buddhism and Its Relation to Women and Prostitution in Thai Society Sandra Avila Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-26-2008 Buddhism and its relation to women and prostitution in Thai society Sandra Avila Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Avila, Sandra, "Buddhism and its relation to women and prostitution in Thai society" (2008). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1343. http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1343 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida BUDDHISM AND ITS RELATION TO WOMEN AND PROSTITUTION IN THAI SOCIETY A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Sandra Avila 2008 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Sandra Avila, and entitled Buddhism and its Relation to Women and Prostitution in Thai Society, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Christin(Qludorf Nathan Katz Steven Heine, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 26, 2008 The thesis of Sandra Avila is approved. Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences Dean George Walker University Graduate School Florida International University, 2008 iH DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis first and foremost, to my parents, because if it wasn't for their unconditional love and encouragement I would not be where I am today. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

Comments on Max Müller's Interpretation of the Buddhist

COMMENTS ON MAX MÜLLER'S INTERPRETATION OF THE BUDDHIST NIRVANA BY G. R. WELBON Rochester, U.S.A. Close, analytical study of ancient Indian religious terminology is a demanding discipline today engaged in by only a few scholars 1). Compounding the impressive difficulties encountered in such investiga- tions, it will be noticed, some of the terms have become incorporated into the vocabulary of contemporary non-Indians. Sanctified by several decades of inclusion in dictionaries of the various Western European languages, they have acquired an uncritical significance which makes it all the more difficult to assess their "original" and contextual signifi- cations in the Indian thought schemata. Among the terms most bedeviling in its complexity of nuance is that of nirvdna according to Buddhist usage. Recently, the distinguished Belgian scholars, Ludo and Rosane Rocher, have expressed some of the frustrations shared by many who have tried to analyse that term: Qu'on conqoive les bouddhistes comme les antagonistes conscients de l'hin- douisme ou comme les "freres des brahmanes des Upanishads", il n'en reste pas moins que le concept bouddhiste de nirvti1la a ete construit sur ou a r6agi contre des elements de 1'hindouisme plus ancien, et qu'a son tour l'hindouisme plus recent s'est enrichi de ou a r6agi contre des elements du nirvana. Nous ne traiterons pas du Nirvana dans la presente 6tude, tout d'abord, parce que le concept hindouiste de mok,?a pose à lui seul, un tel nombre de pro- blemes qu'ils ne pourront être discutés dans leur totalite, et ensuite parce que les bouddhologues, eux-memes, n'en ont resolu les problemes fondamen- 1) Among the most distinguished must be mentioned Louis Renou and Jan Gonda. -

Yuibutsu Yobutsu 唯佛與佛 – Six Translations

Documento de estudo organizado por Fábio Rodrigues. Texto-base de Kazuaki Tanahashi em “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye – Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo” (2013) / Study document organized by Fábio Rodrigues. Main text by Kazuaki Tanahashi in “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye - Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo” (2013) 1. Kazuaki Tanahashi e Edward Brown (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye – Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo, 2013) 2. Kazuaki Tanahashi e Edward Brown (Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen, 1985) 3. Gudo Wafu Nishijima and Chodo Cross (Shobogenzo: The True Dharma-eye Treasury, 1999/2007) 4. Rev. Hubert Nearman (The Treasure House of the Eye of the True Teaching, Shasta Abbey Press, 2007) 5. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975) 6. 第三十八 唯佛與佛 (glasgowzengroup.com) 92 唯佛與佛 Yuibutsu yobutsu Eihei Dogen Only a buddha and a buddha Moon in a Dewdrop (1985): Only buddha and buddha 1 1. Undated. Not included in the primary or additional version of TTDE by Dogen. Together with "Birth and Death," this fascicle was included in an Eihei-ji manuscript called the "Secret Treasury of the True Dharma Eye." Kozen included it in the ninety-five-fascicle version. Other translation: Nishiyama and Stevens, vol. 3, pp. 129-35. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975): Only a Buddha can transmit to a Buddha Shasta Abbey (2017): On ‘Each Buddha on His Own, Together with All Buddhas’ 1 Translator’s Introduction: The title of this text is a phrase that Dogen often employs. It is derived from a verse in the Lotus Scripture: “Each Buddha on His own, -

Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem and the 5 Lay Vows – Geshe Tenzin Zopa

Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem and the 5 Lay Vows – Geshe Tenzin Zopa Why take Refuge? If one wishes to optimise this human life, there is much benefit to taking Refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Holding Refuge vows is crucial to those inspired to follow the path of the Buddha. Whether one becomes a child of the Buddha and under the protection of the Buddha or not, is determined at the time when one receives the blessing of Refuge from Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Even though one’s family may follow the Buddha’s path and call themselves Buddhists, if one has not taken Refuge with the full understanding of what Refuge means and involves, one is not yet a Buddhist. Firstly, we need to know that we have obtained this precious human rebirth which has the 8 freedoms and the 10 Endowments which enable us to practice the Path. The Buddha has taught us that with such a precious human rebirth, we are able to embark on the 3 higher trainings namely, morality, concentration and cultivation of wisdom realising emptiness. These are critical if we wish to eradicate samsaric suffering, including that of birth, aging and death. In order to actualise the wisdom realising emptiness, one requires realisations in concentration; in order to gain realisations in concentration, one needs to live in and gain realisations of morality. Without these 3, there can be no antidote to samsara, let alone attaining enlightenment. In relation to the practice of morality, Refuge Vows forms the basis. Refuge Vows are also the foundation of all other vows such as individual liberation / pratimoksha vows, ordination vows, bodhisattva vows, tantric vows. -

Revivals of Ancient Religious Traditions in Modern India: Sāṃkhyayoga And

Revivals of ancient religious traditions in modern India: S khyayoga and Buddhism āṃ KNUT A. JACOBSEN University of Bergen Abstract The article compares the early stages of the revivals of S khyayoga and Buddhism in modern India. A similarity of S khyayoga and Buddhism was that both had disappeared from India andāṃ were re- vived in the modern period, partly based on Orientalistāṃ discoveries and writings and on the availability of printed books and publishers. Printed books provided knowledge of ancient traditions and made re-establishment possible and printed books provided a vehicle for promoting the new teachings. The article argues that absence of com- munities in India identified with these traditions at the time meant that these traditions were available as identities to be claimed. Keywords: Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Hariharānanda Āraṇya, Navayana Buddhism, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries both S khyayoga and Indian Buddhism were revived in India. In this paper I compare and contrast these revivals, and suggest why they happened. S khyayogaāṃ and Buddhism had mainly disappeared as living traditions from the central parts of India before the modern period and their absence openedāṃ them to the claims of various groups. The only living S khyayoga monastic tradition in India based on the Pātañjalayogaśāstra, the K pil Ma h tradition founded by Harihar nanda ya (1869–1947), wasāṃ a late nineteenth-century re-establishment (Jacob- sen 2018). There were no monasticā ṭ institutions of S khyayoga saṃānyāsins basedĀraṇ on the Pātañjalayogaśāstra in India in 1892, when ya became a saṃnyāsin, and his encounter with the teachingāṃ of S mkhyayoga was primarily through a textual tradition (Jacobsen 2018). -

The Buddhist Six-Worlds Model of Consciousness and Reality

THE BUDDHIST SIX-WORLDS MODEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS AND REALITY Ralph Metzner Sonoma, California Historically there have been two main metaphors for consciousness, one spatial or topographical, the other temporal or biographical (Metzner, 1989). The spatial meta phor is expressed in conceptions of consciousness as like a territory, a terrain, or a field, a state one can enter into or leave, or like empty space, as in the Buddhist notion of sunyata.We could speculate that people who unconsciously adhere to a spatial conception of consciousness would tend to a certain kind of fixity of perception and worldview. The "static" aspects of experience might be in the foreground of aware ness, and there could be a craving for stability and persistence. From this point of view, ordinary waking consciousness is the preferred state, and "altered states" are viewed with some anxiety and suspicion-as if an "altered" state is automatically abnormal or pathological in some way. This is close to the attitude of mainstream Western thought toward alterations of consciousness: even the rich diversity of dreamlife and the changed awareness possible with introspection, psychotherapy, or meditation is regarded with suspicion by the dominant extraverted worldview. The temporal metaphor for consciousness on the other hand, is seen in conceptions such as William James' "stream of thought," or the stream of awareness, or the "flow experience"; as well as in developmental theories of consciousness going through various stages. Historically and cross-culturally, we see the temporal metaphor emphasized in the thought of the pre-Socratic philosophers Thales and Heraclitus, in the Buddhist teachings of impermanence (anicca), and in the Taoist emphasis on the flows and eddies of water as the basic underlying pattern of all being. -

Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Handbook Version

Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study material for your retreat at Tiratanaloka Page 1 of 43 Edited by Vandananjyoti, Version 2:1, July 2020 Table of Contents Introduction to the Handbook Study Area 1. Centrality of Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study Area 2. Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study Area 3. Opening of the Dharma Eye and Stream Entry Study Area 4. Going Forth Study Area 5. The Altruistic Dimension of Going for Refuge and Joining the Order Page 2 of 43 Edited by Vandananjyoti, Version 2:1, July 2020 Introduction to the Handbook The purpose of this handbook is to give you the opportunity to look in depth at the material that we will be studying on the Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels retreat at Tiratanaloka. In this handbook we give you material to study for each area we’ll be studying on the retreat. We will also have some talks on the retreat itself where the team will bring out their own personal reflections on the topics covered. As well as the study material in this handbook, it would be helpful if you could read Sangharakshita’s book ‘The History of My Going for Refuge’. You can buy this from Windhorse Publications. There is also some optional extra study material at the beginning of each section. Some of the optional material is in the form of talks that can be downloaded from the Free Buddhist Audio website at www.freebuddhistaudio.com. These aren’t by any means exhaustive - Free Buddhist Audio is growing and changing all the time so you may find other material equally relevant! For example, at the time of writing, Vessantara has just completed a series of talks called ‘Aspects of Going for Refuge’ (2016) at Cambridge Buddhist Centre.