Readings of Dōgen's Treasury of the True Dharma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZEN at WAR War and Peace Library SERIES EDITOR: MARK SELDEN

ZEN AT WAR War and Peace Library SERIES EDITOR: MARK SELDEN Drugs, Oil, and War: The United States in Afghanistan, Colombia, and Indochina BY PETER DALE SCOTT War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century EDITED BY MARK SELDEN AND ALVIN Y. So Bitter Flowers, Sweet Flowers: East Timor, Indonesia, and the World Community EDITED BY RICHARD TANTER, MARK SELDEN, AND STEPHEN R. SHALOM Politics and the Past: On Repairing Historical Injustices EDITED BY JOHN TORPEY Biological Warfare and Disarmament: New Problems/New Perspectives EDITED BY SUSAN WRIGHT BRIAN DAIZEN VICTORIA ZEN AT WAR Second Edition ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Oxford ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowmanlittlefield.com P.O. Box 317, Oxford OX2 9RU, UK Copyright © 2006 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Cover image: Zen monks at Eiheiji, one of the two head monasteries of the Sōtō Zen sect, undergoing mandatory military training shortly after the passage of the National Mobilization Law in March 1938. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Victoria, Brian Daizen, 1939– Zen at war / Brian Daizen Victoria.—2nd ed. -

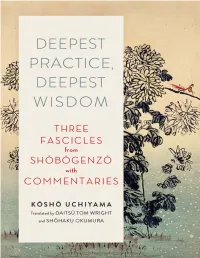

Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

“A magnificent gift for anyone interested in the deep, clear waters of Zen—its great foundational master coupled with one of its finest modern voices.” —JISHO WARNER, former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association FAMOUSLY INSIGHTFUL AND FAMOUSLY COMPLEX, Eihei Dōgen’s writings have been studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. In Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom, Kshō Uchiyama, beloved twentieth-century Zen teacher, addresses himself head-on to unpacking Dōgen’s wisdom from three fascicles (or chapters) of his monumental Shōbōgenzō for a modern audience. The fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include “Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece. At turns poetic and funny, always insightful, this is Zen wisdom for the ages. KŌSHŌ UCHIYAMA was a preeminent Japanese Zen master instrumental in bringing Zen to America. The author of over twenty books, including Opening the Hand of Thought and The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo, he died in 1998. Contents Introduction by Tom Wright Part I. Practicing Deepest Wisdom 1. Maka Hannya Haramitsu 2. Commentary on “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” Part II. Refraining from Evil 3. Shoaku Makusa 4. Commentary on “Shoaku Makusa” Part III. Living Time 5. Uji 6. Commentary on “Uji” Part IV. Comments by the Translators 7. Connecting “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” to the Pāli Canon by Shōhaku Okumura 8. Looking into Good and Evil in “Shoaku Makusa” by Daitsū Tom Wright 9. -

Yuibutsu Yobutsu 唯佛與佛 – Six Translations

Documento de estudo organizado por Fábio Rodrigues. Texto-base de Kazuaki Tanahashi em “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye – Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo” (2013) / Study document organized by Fábio Rodrigues. Main text by Kazuaki Tanahashi in “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye - Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo” (2013) 1. Kazuaki Tanahashi e Edward Brown (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye – Zen Master Dogen's Shobo Genzo, 2013) 2. Kazuaki Tanahashi e Edward Brown (Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen, 1985) 3. Gudo Wafu Nishijima and Chodo Cross (Shobogenzo: The True Dharma-eye Treasury, 1999/2007) 4. Rev. Hubert Nearman (The Treasure House of the Eye of the True Teaching, Shasta Abbey Press, 2007) 5. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975) 6. 第三十八 唯佛與佛 (glasgowzengroup.com) 92 唯佛與佛 Yuibutsu yobutsu Eihei Dogen Only a buddha and a buddha Moon in a Dewdrop (1985): Only buddha and buddha 1 1. Undated. Not included in the primary or additional version of TTDE by Dogen. Together with "Birth and Death," this fascicle was included in an Eihei-ji manuscript called the "Secret Treasury of the True Dharma Eye." Kozen included it in the ninety-five-fascicle version. Other translation: Nishiyama and Stevens, vol. 3, pp. 129-35. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975): Only a Buddha can transmit to a Buddha Shasta Abbey (2017): On ‘Each Buddha on His Own, Together with All Buddhas’ 1 Translator’s Introduction: The title of this text is a phrase that Dogen often employs. It is derived from a verse in the Lotus Scripture: “Each Buddha on His own, -

BEYOND THINKING a Guide to Zen Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK Spiritual practice is not some kind of striving to produce enlightenment, but an expression of the enlightenment already inherent in all things: Such is the Zen teaching of Dogen Zenji (1200–1253) whose profound writings have been studied and revered for more than seven hundred years, influencing practitioners far beyond his native Japan and the Soto school he is credited with founding. In focusing on Dogen’s most practical words of instruction and encouragement for Zen students, this new collection highlights the timelessness of his teaching and shows it to be as applicable to anyone today as it was in the great teacher’s own time. Selections include Dogen’s famous meditation instructions; his advice on the practice of zazen, or sitting meditation; guidelines for community life; and some of his most inspirational talks. Also included are a bibliography and an extensive glossary. DOGEN (1200–1253) is known as the founder of the Japanese Soto Zen sect. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Translators Reb Anderson Edward Brown Norman Fischer Blanche Hartman Taigen Dan Leighton Alan Senauke Kazuaki Tanahashi Katherine Thanas Mel Weitsman Dan Welch Michael Wenger Contributing Translator Philip Whalen BEYOND THINKING A Guide to Zen Meditation Zen Master Dogen Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi Introduction by Norman Fischer SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue -

The Existential Moment: Rereading Dōgen’S Theory of Time

THE EXISTENTIAL MOMENT: REREADING DŌGEN’S THEORY OF TIME Rein Raud Department of World Cultures at the University of Helsinki, and Estonian Institute of Humanities at Tallinn University [email protected] Among all aspects of Dōgen’s philosophical thought, his theory of time has without doubt received the most attention. Even in English there exist two book-length studies of this topic,1 and a multitude of other authors who have treated Dōgen have also extensively commented on the subject.2 This is with good reason. Without an inter- pretation of Dōgen’s ideas on time it is very difficult to approach any other aspect of his thought, or even to form an adequate understanding of his basic concepts. And yet most previous studies of Dōgen’s time theory as well as English translations of the “Uji” (usually translated as “Being-time”) fascicle of the Shōbōgenzō have, to my knowledge, assumed without questioning certain presuppositions on the nature of time, which makes Dōgen’s theory much more complicated and in some respects almost impossible to understand (a position that I have myself also shared earlier3 and which has influenced many classic treatments4 as well as all the most influential English translations5 of the text). Notably, they have viewed time as primarily dura- tional. This article presents an effort to reinterpret the concept of time in Dōgen’s theory from a different position, with stress on the momentary rather than the dura- tional, and to offer an alternative reading of the Uji fascicle as well as certain other key passages in Dōgen’s work that, I hope, will enable a less complicated and more lucid understanding of his ideas. -

Bowz Liturgy 2011.Corrected

Boundless Way Zen LITURGY BOOK SECOND EDITION _/\_ All buddhas throughout space and time, All honored ones, bodhisattva-mahasattvas, Wisdom beyond wisdom, Maha Prajna Paramita. Page 1 Notation ring kesu (bowl gong) muffle kesu (bowl gong) ring small bell 123 ring kesu or small bell on 1st, 2nd, or 3rd repetition accordingly underlined syllables indicate the point at which underlined bells are rung 1 mokugyo (wooden drum) beat once after then on each syllable taiko (large drum) beat once after then in single or double beats -_^ notation for tonal chanting (mid-low-high shown in this example) WORDS IN ALL CAPS are CHANTED by chant-leader only [Words in brackets & regular case] are spoken by chant-leader only {Words in braces} are CHANTED or spoken or sung !by chant-leader only 1st time, and by everyone subsequently (words in parenthesis) are not spoken, chanted, or sung at all _/\_ ! place or keep hands palm-to-palm in gassho, or hold liturgy book in gassho -(0)-! place or keep hands in zazen mudra, or hold liturgy book open !with little fingers and thumbs on the front of the book and !middle three fingers on the back seated bow at end of chant, or after final repetition Beginning our sutra service I vow with all beings To join my voice with all voices And give life to each word as it comes. —Robert Aitken Language cannot reach it, hearing and seeing cannot touch it. In this single beam of illumination, you genuinely wander in practice. Use your vitality to enact this. -

The Way of Zazen Rindô Fujimoto Rôshi

The Way of Zazen Rindô Fujimoto rôshi Ce texte est l'un des premiers (peut-être même le tout premier) manuels de méditation à avoir été publié en langue anglaise. Il s'agit de la traduction d'un opuscule, à l'origine une conférence donnée par le maître Sôtô Rindô Fujimoto. Le texte fut publié en 1966 par Elsie P. Mitchell (de l'Association Bouddhiste de Cambridge) qui avait reçu, quatre ans plus tôt au Japon, les voeux bouddhistes de Fujimoto. Rindô Fujimoto, né en 1894, pratiqua notamment sous la direction de Daiun Sôgaku Harada (1870-1961), le maître Sôtô qui intégra la pratique des kôan, pour revenir par la suite à la pratique, plus orthodoxe, du "juste s'asseoir" (shikantaza). Il fut également responsable de la méditation (tantô) au monastère de Sôjiji à Yokohama. Reproduit avec l'aimable autorisation d'Elsie P. Mitchell et de David Chadwick (www.cuke.com). On lira sur le site la version française de ce texte, La Voie de zazen. The Way of Zazen, Rindô Fujimoto, Rôshi, translated by Tetsuya Inoue, Jushoku and Yoshihiko Tanigawa, with an Introduction by Elsie P. Mitchell, Cambridge Buddhist Association, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1966 (Published by Cambridge Buddhist Association Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1966, 3 Craigie Street, Cambridge 38, Mass., Second Printing, copyrighted in Japan, 1961 - All Rights reserved) Preface The author of this essay, Rindô Fujimoto, Rôshi (Zen Master), was born near Kobe in 1894. An official's son, he was ordained in the Sôtô Zen sect before his teens, and since that time has devoted his life to the study and practice of Buddhism. -

Investigating the Moment When Solutions Emerge in Problem Solving

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2018 Investigating the Moment when Solutions emerge in Problem Solving Losche, Frank http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/12838 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Investigating the Moment when Solutions emerge in Problem Solving by Frank Lösche A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Computing, Electronics and Mathematics Plymouth 2018 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. Acknowledgements This work has been funded through a full studentship by the University of Ply- mouth and supported by the additional training receievd through the CogNovo programme. CogNovo is funded by EU Marie Skłodowska-Curie programme (FP7- PEOPLE-2013-ITN-604764) and the University of Plymouth. This work is part of the CogNovo Doctoral Training Programme and has been supervised by the director of studies Dr. Guido Bugmann (School of Computing, Electronics and Mathematics) and the additional supervisors Dr. -

Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan

Soto Zen in Medieval Japan Kuroda Institute Studies in East Asian Buddhism Studies in Ch ’an and Hua-yen Robert M. Gimello and Peter N. Gregory Dogen Studies William R. LaFleur The Northern School and the Formation of Early Ch ’an Buddhism John R. McRae Traditions of Meditation in Chinese Buddhism Peter N. Gregory Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought Peter N. Gregory Buddhist Hermeneutics Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Paths to Liberation: The Marga and Its Transformations in Buddhist Thought Robert E. Buswell, Jr., and Robert M. Gimello Studies in East Asian Buddhism $ Soto Zen in Medieval Japan William M. Bodiford A Kuroda Institute Book University of Hawaii Press • Honolulu © 1993 Kuroda Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 93 94 95 96 97 98 5 4 3 2 1 The Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism and Human Values is a nonprofit, educational corporation, founded in 1976. One of its primary objectives is to promote scholarship on the historical, philosophical, and cultural ramifications of Buddhism. In association with the University of Hawaii Press, the Institute also publishes Classics in East Asian Buddhism, a series devoted to the translation of significant texts in the East Asian Buddhist tradition. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bodiford, William M. 1955- Sotd Zen in medieval Japan / William M. Bodiford. p. cm.—(Studies in East Asian Buddhism ; 8) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8248-1482-7 l.Sotoshu—History. I. Title. II. Series. BQ9412.6.B63 1993 294.3’927—dc20 92-37843 CIP University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources Designed by Kenneth Miyamoto For B. -

Putting Dogen on the Map Autumn 2007

Putting Dōgen on the Map Rev. Wilfrid Powell — Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey, Northumberland – UK — (Great Master Dōgen is a key figure in the Serene Reflection Meditation tradition because he is the monk who brought the tradi- tion from China to Japan in 1227. This article is an edited version of a talk about Dōgen’s background given at Throssel earlier this year. I am grateful to the people who kindly took the time to read through the article and for their helpful suggestions.) s the influence and the power of the Buddhist church increased, Aits aims became more and more temporal. It began to inter- fere in political affairs; its abbots built in and around the capital or in the provinces great monasteries such as Mt Hiei, Koyasan, Miidera and others and filled them with armed monks; its prel- ates were involved in intrigues around the throne (it is possible that the removal of the capital from Nara to Kyoto may have been due to imperial fear of priestly statecraft); it even made attempts to establish direct ecclesiastical control over the state. The various sects too began to quarrel amongst themselves…Monastery fought monastery; sect fought sect; while the monks of Mt Hiei and other priestly strongholds trooped down so often in their thousands to overawe the capital that the Emperor Shirakawa once exclaimed [in 1198] ‘Three things there are which I cannot control — the river Kamo in flood, the fall of the dice, and the monks of Mt Hiei 1. The Political and Social Background The Japan of 1200 into which Dōgen was born was in tur- moil: political, social, moral and religious. -

Advaita Vedanta and Zen Buddhism : Deconstructive Modes of Spiritual Inquiry / Leesa S

Advaita Vedānta and Zen Buddhism This page intentionally left blank Advaita Vedānta and Zen Buddhism Deconstructive Modes of Spiritual Inquiry Leesa S. Davis Continuum International Publishing Group The Tower Building 80 Maiden Lane 11 York Road Suite 704 London SE1 7NX New York NY 10038 www.continuumbooks.com © Leesa S. Davis 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-8264-2068-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Davis, Leesa S. Advaita Vedanta and Zen Buddhism : deconstructive modes of spiritual inquiry / Leesa S. Davis. p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-0-8264-2068-8 (HB) ISBN-10: 0-8264-2068-0 (HB) 1. Advaita. 2. Vedanta. 3. Zen Buddhism. 4. Deconstruction. I. Title. B132.A3D38 2010 181'.482--dc22 2009043205 Typeset by Free Range Book Design & Production Limited Printed and bound in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group In Memoriam Patricia Mary Davis 1930–1987 This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xi Introduction: Experiential Deconstructive Inquiry xiii Part One: Foundational Philosophies and Spiritual Methods 1. Non-duality in Advaita Vedānta and Zen Buddhism 3 Ontological differences and non-duality 3 Meditative inquiry, questioning, and dialoguing as a means to spiritual insight 8 The ‘undoing’ or deconstruction of dualistic conceptions 12 2. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 6 Fall 2004 TWO SPECIAL SECTIONS: ESSAYS CELEBRATING THE THIRTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE INSTITUTE OF BUDDHIST STUDIES, AND SIGN, SYMBOL, AND BODY IN TANTRA FRONT COVER PACIFIC WORLD: Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series, Number 6 Fall 2004 SPINE PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies HALF-TITLE PAGE i REVERSE HALF TITLE ii PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 6 Fall 2004 TWO SPECIAL SECTIONS: ESSAYS CELEBRATING THE THIRTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE INSTITUTE OF BUDDHIST STUDIES, AND SIGN, SYMBOL, AND BODY IN TANTRA TITLE iii Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of histori- cal, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is dis- tributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, P.O. Box 390460, Mountain View, CA 94039-0460, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of Buddha Dharma Kyokai (Society), Inc. of Berkeley, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately 20 standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full bibliographic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (15th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references.