The Battle for Buttons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STUDY GUIDE Prepared by Maren Robinson, Dramaturg

by Susan Felder directed by William Brown STUDY GUIDE Prepared by Maren Robinson, Dramaturg This Study Guide for Wasteland was prepared by Maren Robinson and edited by Kerri Hunt and Lara Goetsch for TimeLine Theatre, its patrons and educational outreach. Please request permission to use these materials for any subsequent production. © TimeLine Theatre 2012 — STUDY GUIDE — Table of Contents About the Playwright ........................................................................................ 3 About the Play ................................................................................................... 3 The Interview: Susan Felder ............................................................................ 4 Glossary ............................................................................................................ 11 Timeline: The Vietnam War and Surrounding Historical Events ................ 13 The History: Views on Vietnam ...................................................................... 19 The Context: A New Kind of War and a Nation Divided .............................. 23 Prisoners of War and Torture ......................................................................... 23 Voices of Prisoners of War ............................................................................... 24 POW Code of Conduct ..................................................................................... 27 Enlisted vs. Drafted Soldiers .......................................................................... 28 The American -

Model Builder April 1976

[R/C ELECTRIC FLIGHT SYSTEMS*__ ) from A L L B A L S A SI Q NED FOR RSTRO FLIGHT inc. ASTRO 25 PIONEERS IN SILENT FLIGHT 13377 Beach Avenue $39.95 J Venice, California 90291 2 CHANNEL SPORT TRAINER DESIGNED FOR ASTRO 5 · 10 MOTORS ALL BALSA All Βλ Ιλλ I Spruce Construction Atm — ISO So In DT SIGHT D top ASTRO >5 T UC T R IC OR IS GLOW MOTORS Ffylne - M - «41 • ELECTRA-FLI NEW R/C SYSTEM FOR »STB0 10, IS, 1 2 6 ^ MtMHUTTI» »DO A ANALYZER — RAPID CHARGER DtDTlIO·•ECfrvl* COMTMt ΠΜΜ A R/C SYSTEM ANALYZER-RAPID CHARGER $38.00 FIELD CHARGER NEW MARINE SYSTEMS (Astro Pup) ASTRO - 020 ASTRO -10 This is the answer to your battery problems. Two ASTRO-23 *19.95 F.F. ASTRO 15 $22.95 R.C. years of development by the company that k tows batteries best — Astro Flight — has resulted in a great little unit that will: • Charge your receiver in 15 minutes. • Charge your transmitter batteries in 15 min. • Test for a high resistance cell in two min. • Test for a shorted cell. • Indicate the capacity remaining after a day’s fly ing in 10 minutes. MOTORS SYSTEMS • Measure the capacity of a fully charged battery in ASTRO $10.95 $27.95 10 minutes. SPECIAL TWIN PACKS This unit tells you what you have and allows ASTRO-02 $ 30.00 ASTRO 10 $32.95 $59.95 you to do something about it at the field, not ASTRO- 5 $ 50.00 ASTRO 15 $32.95 $84.95 after you get home. -

Tank Gunnery

Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com MHI Copy 3 FM 17-12 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FIELD MANUAL TANK GUNNERY HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY NOVEMBER 1964 Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com PREPARE TO FIRE Instructional Card (M41A3, M48, and M60 Tanks) TANK COMMANDER GUNNER DRIVER LOADER Commond: PREPARE TO Observe looder's actionr in Cleon periscopes, Check indicotor tape for FIRE. making check of replenisher in. lower seat, close proper amount of recoil oil Inspect coaxial machine- dicotor tope. Clean nd inspect hoatch, nd turn in replenilher. Check posi- gun ond telescope ports gunner s direct-fire sights. Check on master switch. tion of breechblock crank to ensure gun shield operaoion of sight covers if op. stop. Open breech (assisted cover is correctly posi- cable. Check instrument lights. by gunner); inspect cham- tioned ond clomps are Assist loader in opening breech. ber ond tube, and clote secure. Clean exterior breech. Check coxial lenses and vision devices. mochinegun and adjust and clean ond inspect head space if opplicble. commander's direct-fire Check coaxial machinegun sight(s). Inspect cupolao mount ond odjust solenoid. sowed ammunilion if Inspect turret-stowed am. applicable. munitlon. Command: CHECK FIR- Ploce main gun safety in FIRE Start auxiliary Place moin gun safety ING SWITCHES. position if located on right side engine (moin en- in FIREposition if loated If main gun has percus- of gun. Turn gun switch ON. gin. if tank has on left side of gun. If sion mechanism, cock gun Check firing triggers on power no auxiliary en- moin gun hoaspercussion for eoch firing check if control handle if applicable. -

Message… Dear MOAA HA Members, in This Issue >>>

Houston Area PO Box 1082 Houston, TX 77251-1082 www.moaahoustonarea.com m March 2021 Issue – Newsletter to Members President’s Message… Dear MOAA HA Members, In this issue >>> This is my first message to ➢ President’s Message, Robin P. Ritchie, COL, you as your new President Infantry, USAR (Ret) ➢ March 2021 Chapter Events for 2021. The first order of ➢ VA Secretary: ‘Urgent’ Review Planned for Agent business is a very profound Orange Benefit Expansion and heart felt “THANK YOU” ➢ MOAA HA March Preliminary Financial Statement to our previous President ➢ February MOAA Chapter Luncheon Joe Willoughby. As some of ➢ Surviving Spouse Corner you know, Joe and I traded ➢ March Guest Speaker – Col EA “Buddy” Grantham places and he will continue – Texas State Guard to serve as Vice Present. ➢ The National Vietnam War Museum This decision will make for continued coordinated ➢ Lawmakers Want to Make All Vets, Some team. COL Frank Tricomi continues to serve as our Caregivers Eligible for VA COVID-19 Vaccines treasurer as well as Secretary and does a stellar job ➢ Dusters in Vietnam with both positions…Thank you, Frank. ➢ Chaplain’s Corner ➢ Membership Application/Renewal Form Last month Joe wrote about optimism for this year. Last year was tough on all of us with the COVID-19 March… virus and its restrictions. I echo Joe’s optimism. Vaccinations are well underway and there are strong Upcoming Chapter Events: indicators that we are on the road to normalcy. Last month our monthly luncheon was an in person Wednesday, March 24, 2021 @ noon gathering with a really great turn out. -

POETRY OFFERINGS from David W. Mitchell

1 POETRY OFFERINGS from David W. Mitchell 2 Photography of David Mitchell by Ken Roberts Cover photography by Jeremiah Trilli Line drawing by Summer Breeze Published by Motherbird Books Silver City, New Mexico motherbird.com © David W. Mitchell 2008 3 Index A Dark Hole In Time . 8 A Gift . 9 A Lovely Day for Borscht Fish . 10 A Modern Carollette for Dodgson . 11 Abroad Among the Limbless . 12 Adagio in Zzzzz Minor . 13 Afternoon of a Biblioparadisiac . 14 Ah Dylan, Dylan . 15 An Olympian Lesson . 16 Apostatic Succession . 17 Ballad of Saint Louis, the Unfrocked Cardinal 18 Belle Ardoise I, The . 20 Blatissimus . 21 Blue Writer, The . 22 Carmel I . 23 Carmel II . 25 Chelsea . 27 Compass Rose and the Gypsy Will . 28 Compendium Humanum . 29 Concertina in F-Stop Major . 31 Critique . 32 Cursive Reclaimed . 33 Cutting Corners I; Cutting Corners II . 34 Departure of Roses, The . 35 Diasporulation . 36 Disappearance . 37 Drizzle . 38 Doubling Duplicity . 39 Eleven Red-Haired Men . 40 Encampment, The . 41 Epitaph for Floyd . 42 Fangs . 43 Father Time Contemplates Mass . 44 4 Fingersongs- I . 45 For Edna, and John, and All . 46 For Jessica and the Williams . 47 For Mimi Farina: Bread and Roses . 51 From A to Z and Back Again . 52 Goulashification . 53 Heard On the Concertina Wire . 54 Helicocochoidal Figmentation. 55 Hexing the Circle . 56 Hillock and the Holly, The . 57 How I knew What to Do . 59 In Praise of Thumbs . 60 In Praise of Thumbs II . 61 In the Mailstrom . 63 In Sacramental Jeans . 64 Infinite Regress of Dawn, The . -

Air Base Defense Rethinking Army and Air Force Roles and Functions for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N ALAN J. VICK, SEAN M. ZEIGLER, JULIA BRACKUP, JOHN SPEED MEYERS Air Base Defense Rethinking Army and Air Force Roles and Functions For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR4368 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0500-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The growing cruise and ballistic missile threat to U.S. Air Force bases in Europe has led Headquarters U.S. -

M551 SHERIDAN 1941–2001 Tanks US Airmobile

NVG153cover.qxd:Layout 1 27/11/08 10:16 Page 1 NEW VANGUARD • 153 The design, development, operation and history of the machinery of warfare through the ages NEW VANGUARD • 153 • VANGUARD NEW M551 SHERIDAN M551 SHERIDAN US Airmobile Tanks 1941–2001 US Airmobile Tanks 1941–2001 M551 Since the advent of airmobile warfare, there have been numerous SHERIDAN SHERIDAN attempts to support paratroopers with attached armored vehicles. This book tells the story of the US experience with airmobile tanks, starting with their efforts in World War II. However, full success was not achieved until the production of the M551 Sheridan. The history of this tank provides the focal point of this book, highlighting the difficulties of combining heavy firepower in a chassis light enough for airborne delivery. The book examines its controversial debut in Vietnam, and its subsequent combat history in Panama and Operation Desert Storm, before it rounds out the story by examining the failed attempts to replace the Sheridan with other armored vehicles. Full color artwork Illustrations Unrivaled detail Cutaway artwork US $17.95 / CAN $19.95 STEVEN J ZALOGA ISBN 978-1-84603-391-9 OSPREY 51795 PUBLISHING 9 781846 033919 O SPREY WWW.OSPREYPUBLISHING.COM STEVEN J ZALOGA ILLUSTRATED BY TONY BRYAN © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NVG153title.qxd:Layout 1 26/11/08 11:39 Page 1 NEW VANGUARD • 153 M551 SHERIDAN US Airmobile Tanks 1941–2001 STEVEN J ZALOGA ILLUSTRATED BY TONY BRYAN © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NVG153_PAGEScorrex2.qxd:NVG153 9/4/09 16:15 Page 2 First published in Great Britain in 2009 by Osprey Publishing, AUTHOR’S NOTE Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford, OX2 0PH, UK The author would especially like to thank Colonel Russ Vaughan (USAR – 443 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016, USA Ret’d) for his help with the photos for this book and for sharing his E-mail: [email protected] recollections of the Sheridan from his service with the 2nd Armored Cavalry and 82nd Airborne divisions. -

Thunder Chickens Take Osprey To

Fort Worth, Texas November 2007, Issue 20 OOHRAH! Thunder Chickens take Osprey to war The V-22 Osprey is now in service defending our country after a quarter century of research and development – and a great deal of work. Ten MV-22s from Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 263 (VMM-263) arrived in Iraq in early October. Known as the “Thunder Chickens,” they are stationed at Al Asad Air Base west of Baghdad. “It has been a long time coming,” said Art Gravley, the chief Bell engineer for the V-22. “With all the different problems we’ve had in the program in terms of threats of cancellation and accidents, it’s such a satisfying thing to get to this point.” The deployment means a great deal to those who have had their hands in the tiltrotor, many of them for years. For Bell, creating the Osprey is a team effort. Large sections of the aircraft, particularly the wings, are constructed at the Advanced TOP: Marines of VMM-263 gather in front of an Osprey at Al Asad Air Base, Iraq. Marine Corps photo Composite Center (ACC) in Hurst. ABOVE: Marines attached to Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron (VMM) 263 board an MV-22 Osprey on the The rotors that keep it aloft are made flight deck of the USS Wasp as they prepare to transit to their final operational destination in Iraq. This at the Rotor Systems Center (RSC). marks the first combat deployment of the Osprey.U.S. Navy photo The gears and transmissions that make it all possible come to life at that we could help the guys over there fighting,” officer, who called it “pretty cool.” the Drive Systems Center (DSC) he said. -

Table of Contents

CCrriittiiccaall TTeecchhnnooll ooggyy EEvveennttss iinn tthhee Development of the Abrams Tank Development of the Abrams Tank PPrroojjeecctt HHiinnddssiigghhtt RReevviissiitteedd Richard Chait, John Lyons, and Duncan Long Center for Technology and National Security Policy National Defense University December 2005 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. All information and sources for this paper were drawn from unclassified materials. Richard Chait is a Distinguished Research Professor at the Center for Technology and National Security Policy (CTNSP), National Defense University. He was previously Chief Scientist, Army Material Command, and Director, Army Research and Laboratory Management. Dr. Chait received his Ph.D in Solid State Science from Syracuse University and a B.S. degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. John W. Lyons is a Distinguished Research Professor at CTNSP. He was previously director of the Army Research Laboratory and director of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Dr. Lyons received his Ph.D from Washington University. He holds a B.A. from Harvard. Duncan Long is a Research Associate at CTNSP. He holds a Master of International Affairs degree from the School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, and a B.A. from Stanford University. Acknowledgments. A project of this magnitude and scope could not have been conducted without the involvement of many people. Their cooperation and willingness to recount events that happened many years ago made this paper possible. The Army Science and Technology (S&T) Executive, Dr. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide

WORLDWIDE EQUIPMENT GUIDE TRADOC DCSINT Threat Support Directorate DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. Worldwide Equipment Guide Sep 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Page Memorandum, 24 Sep 2001 ...................................... *i V-150................................................................. 2-12 Introduction ............................................................ *vii VTT-323 ......................................................... 2-12.1 Table: Units of Measure........................................... ix WZ 551........................................................... 2-12.2 Errata Notes................................................................ x YW 531A/531C/Type 63 Vehicle Series........... 2-13 Supplement Page Changes.................................... *xiii YW 531H/Type 85 Vehicle Series ................... 2-14 1. INFANTRY WEAPONS ................................... 1-1 Infantry Fighting Vehicles AMX-10P IFV................................................... 2-15 Small Arms BMD-1 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-17 AK-74 5.45-mm Assault Rifle ............................. 1-3 BMD-3 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-19 RPK-74 5.45-mm Light Machinegun................... 1-4 BMP-1 IFV..................................................... 2-20.1 AK-47 7.62-mm Assault Rifle .......................... 1-4.1 BMP-1P IFV...................................................... 2-21 Sniper Rifles..................................................... -

Archie to SAM a Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense

Archie to SAM A Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense Second Edition KENNETH P. WERRELL Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2005 Air University Library Cataloging Data Werrell, Kenneth P. Archie to SAM : a short operational history of ground-based air defense / Kenneth P. Werrell.—2nd ed. —p. ; cm. Rev. ed. of: Archie, flak, AAA, and SAM : a short operational history of ground- based air defense, 1988. With a new preface. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-136-8 1. Air defenses—History. 2. Anti-aircraft guns—History. 3. Anti-aircraft missiles— History. I. Title. 358.4/145—dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public re- lease: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii In memory of Michael Lewis Hyde Born 14 May 1938 Graduated USAF Academy 8 June 1960 Killed in action 8 December 1966 A Patriot, A Classmate, A Friend THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii DEDICATION . iii FOREWORD . xiii ABOUT THE AUTHOR . xv PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION . xvii PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION . xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xxi 1 ANTIAIRCRAFT DEFENSE THROUGH WORLD WAR II . 1 British Antiaircraft Artillery . 4 The V-1 Campaign . 13 American Antiaircraft Artillery . 22 German Flak . 24 Allied Countermeasures . 42 Fratricide . 46 The US Navy in the Pacific . -

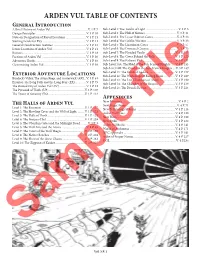

ARDEN VUL TABLE of CONTENTS General Introduction a Brief History of Arden Vul

ARDEN VUL TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction A Brief History of Arden Vul ..................................................V. 1 P. 7 Sub-Level 1: The Tombs of Light ...........................................V. 3 P. 3 Design Principles ...................................................................V. 1 P. 10 Sub-Level 2: The Hall of Shrines ..........................................V. 3 P. 11 Note on Designation of Keyed Locations ...........................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 3: The Lesser Baboon Caves ...............................V. 3 P. 23 Starting Levels for PCs ..........................................................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 4: The Goblin Warrens........................................ V. 3 P. 33 General Construction Features ...........................................V. 1 P. 12 Sub-Level 5: The Lizardman Caves .....................................V. 3 P. 57 Iconic Locations of Arden Vul .............................................V. 1 P. 14 Sub-Level 6: The Drowned Canyon ....................................V. 3 P. 73 Rumors ....................................................................................V. 1 P. 18 Sub-Level 7: The Flooded Vaults .......................................V. 3 P. 117 Factions of Arden Vul ...........................................................V. 1 P. 30 Sub-Level 8: The Caves Behind the Falls ..........................V. 3 P. 125 Adventure Hooks ...................................................................V. 1 P. 48 Sub-Level 9: The Kaliyani Pits ...........................................V.