Adherence and Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Gladstone Park to Mapesbury

Route 2 - Gladstone Park, Mapesbury Dell and surrounds Route Highlights Just off route up Brook Road, you will see the Paddock War Brent Walks Stroll through Gladstone Park and enjoy the views over Room Bunker, codeword for the A series of healthy walks for all the family to enjoy the city of London and the walled gardens. This route alternative Cabinet War Room also includes historic sites including the remains of Dollis Bunker. An underground 1940’s Hill House, a WWII underground bunker and Old Oxgate bunker used during WWII by Farm. The route finishes by walking through Mapesbury Winston Churchill and the Conservation area to the award-winning Mapesbury Dell. Cabinet, it remains in its original Route 2 - Gladstone Park, state next to 107 Brook Road. You can take a full tour of 1 Start at Dollis Hill Tube Station and 2 take the Burnley the underground bunker twice a year. Purpose-built from Mapesbury Dell and surrounds Road exit. Go straight up 3 Hamilton Road. At the end reinforced concrete, this bomb-proof subterranean war of Hamilton Road turn left onto 4 Kendal Road and then citadel 40ft below ground has a map room, cabinet room right onto 5 Gladstone Park. Walk up to the north end and offices and is housed within a sub-basement protected of the park when you are nearing the edge 6 turn right. by a 5ft thick concrete roof. In the north east corner of the park you will see the Holocaust Memorial and the footprint of Dollis Hill House. Old Oxgate Farm is a Grade II Exit the park at 7 and walk up Dollis Hill Lane, and turn listed building thought to be left onto Coles Green Road 8. -

Uranium 2001: Resources, Production and Demand

A Joint Report by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Atomic Energy Agency Uranium 2001: Resources, Production and Demand NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: − to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; − to contribute to sound economic expansion in Member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and − to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original Member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The following countries became Members subsequently through accession at the dates indicated hereafter: Japan (28th April 1964), Finland (28th January 1969), Australia (7th June 1971), New Zealand (29th May 1973), Mexico (18th May 1994), the Czech Republic (21st December 1995), Hungary (7th May 1996), Poland (22nd November 1996), Korea (12th December 1996) and the Slovak Republic (14 December 2000). The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD (Article 13 of the OECD Convention). -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

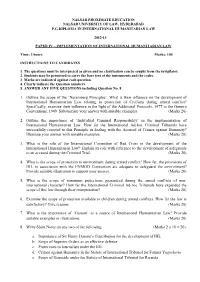

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

Whiteflag Protocol Specification

Whiteflag Protocol Specification Status version 1 status DRAFT 6 date 28 FEB 2019 1 1 Introduction 1.1 Background Current armed conflicts are highly complex, because of the sheer number of parties involved: regular military forces, armed groups, peacekeeping forces, neutral parties such as journalists and non-governmental human-rights and aid organisations, civilians, refugees etc. Even though parties are opposing forces, or neutral organisations that do not want to show any affiliation, they do require to quickly and directly communicate to one or more other parties involved in the conflict in different situations. This is not new. The white flag is the original internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and request for negotiation. A white flag signifies to all that an approaching negotiator is unarmed, with an intent to surrender or a desire to communicate. This standard for a digital white flag protocol, the Whiteflag Protocol, provides a reliable means for both combatant and neutral parties in conflict zones to digitally communicate pre-defined signs and signals using blockchain technology. These sign and signals can also be used to communicate information about natural and man-made disasters, thus creating shared situational awareness beyond conflicts. All in all, the protocol forms the basis for a neutral and open network, the Whiteflag Network, for trusted real-time messaging between parties in conflicts and disaster response. 1.2 Purpose The purpose of the Whiteflag Protocol is to provide an open, real-time, trusted communication channel between any or all parties in conflict and disaster zones, without the requirement for a trusted third party or any specific software or system. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918)

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) by Melanie Tanielian A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Beshara Doumani Professor Saba Mahmood Professor Margaret L. Anderson Professor Keith D. Watenpaugh Fall 2012 The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) © Copyright 2012, Melanie Tanielian All Rights Reserved Abstract The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) By Melanie Tanielian History University of California, Berkeley Professor Beshara Doumani, Chair World War I, no doubt, was a pivotal event in the history of the Middle East, as it marked the transition from empires to nation states. Taking Beirut and Mount Lebanon as a case study, the dissertation focuses on the experience of Ottoman civilians on the homefront and exposes the paradoxes of the Great War, in its totalizing and transformative nature. Focusing on the causes and symptoms of what locals have coined the ‘war of famine’ as well as on international and local relief efforts, the dissertation demonstrates how wartime privations fragmented the citizenry, turning neighbor against neighbor and brother against brother, and at the same time enabled social and administrative changes that resulted in the consolidation and strengthening of bureaucratic hierarchies and patron-client relationships. This dissertation is a detailed analysis of socio-economic challenges that the war posed for Ottoman subjects, focusing primarily on the distorting effects of food shortages, disease, wartime requisitioning, confiscations and conscriptions on everyday life as well as on the efforts of the local municipality and civil society organizations to provision and care for civilians. -

Brent Biennial Walk Dollis Hill → Willesden → Kensal Rise

Twain in 1900. in Twain © ↑ John Rogers at Kensal Rise Library . Library Rise Kensal at Rogers John ↑ Thierry Bal Thierry Souls Avenue. Souls original Reading Room was opened by Mark Mark by opened was Room Reading original https://bit.ly/38Fo2el Map: Google Look out for the audio recording at the end of All All of end the at recording audio the for out Look outside Kensal Rise Community Library. The The Library. Community Rise Kensal outside percolate through the soil from this high ridge. ridge. high this from soil the through percolate Rise and Kensal Green and a map is available available is map a and Green Kensal and Rise stream is fed by underground springs that that springs underground by fed is stream audio trail can be found on the streets of Kensal Kensal of streets the on found be can trail audio Green Cemetery. However, it’s claimed that the the that claimed it’s However, Cemetery. Green and experiences of place. The self-guided self-guided The place. of experiences and Kensal Rise Kensal London, is traditionally believed to rise in Kensal Kensal in rise to believed traditionally is London, encompass people’s subjective viewpoints viewpoints subjective people’s encompass The Counters Creek, one of the lost rivers of of rivers lost the of one Creek, Counters The psychogeography to present stories that that stories present to psychogeography Willesden → → Willesden 11 Possible Source of the Counters Creek Counters the of Source Possible 11 and memories. Rogers uses the methods of of methods the uses Rogers memories. -

Pirates and Impunity: Is the Threat of Asylum Claims a Reason to Allow Pirates to Escape Justice

Pirates and Impunity: Is the Threat of Asylum Claims a Reason to Allow Pirates to Escape Justice Yvonne M. Dutton Abstract Pirates are literally getting away with murder. Modern pirates are attacking vessels, hijacking ships at gunpoint, taking hostages, and injuring and killing crew members.1 They are doing so with increasing frequency. According to the International Maritime Bureau (“IMB”) Piracy Reporting Center’s 2009 Annual Report, there were 406 pirate attacks in 2009—a number that has not been reached since 2003. Yet, in most instances, a culture of impunity reigns whereby nations are not holding pirates accountable for the violent crimes they commit. Only a small portion of those people committing piracy are actually captured and brought to trial, as opposed to captured and released. For example, in September 2008, a Danish warship captured ten Somali pirates, but then later released them on a Somali beach, even though the pirates were found with assault weapons and notes stating how they would split their piracy proceeds with warlords on land. Britain’s Royal Navy has been accused of releasing suspected pirates,7 as have Canadian naval forces. Only very recently, Russia released captured Somali pirates—after a high-seas shootout between Russian marines and pirates that had attacked a tanker carrying twenty-three crew and US$52 million worth of oil.9 In May 2010, the United States released ten captured pirates it had been holding for weeks after concluding that its search for a nation to prosecute them was futile. In fact, between March and April 2010, European Union (“EU”) naval forces captured 275 alleged pirates, but only forty face prosecution. -

NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946 Page numbers in braces refer to IMT, judgment of 1 October 1946, in The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Germany , Part 22 (22nd August ,1946 to 1st October, 1946) 1 {iii} THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL IN SESSOIN AT NUREMBERG, GERMANY Before: THE RT. HON. SIR GEOFFREY LAWRENCE (member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) President THE HON. SIR WILLIAM NORMAN BIRKETT (alternate member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) MR. FRANCIS BIDDLE (member for the United States of America) JUDGE JOHN J. PARKER (alternate member for the United States of America) M. LE PROFESSEUR DONNEDIEU DE VABRES (member for the French Republic) M. LE CONSEILER FLACO (alternate member for the French Republic) MAJOR-GENERAL I. T. NIKITCHENKO (member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) LT.-COLONEL A. F. VOLCHKOV (alternate member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) {iv} THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Against: Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Robert Ley, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walter Funk, Hjalmar Schacht, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Martin