Sagar-XVII.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Plan 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020

STRATEGIC PLAN STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 ELECTION COMMISSION OF SRI LANKA 2017-2020 Department of Government Printing STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) of the Election Commission of Sri Lanka for 2017-2020 “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives... The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will, shall be expressed in periodic ndenineeetinieniendeend shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.” Article 21, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020 I Foreword By the Chairman and the Members of the Commission Mahinda Deshapriya N. J. Abeysekere, PC Prof. S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole Chairman Member Member The Soulbury Commission was appointed in 1944 by the British Government in response to strong inteeneeinetefittetetenteineentte population in the governance of the Island, to make recommendations for constitutional reform. The Soulbury Commission recommended, interalia, legislation to provide for the registration of voters and for the conduct of Parliamentary elections, and the Ceylon (Parliamentary Election) Order of the Council, 1946 was enacted on 26th September 1946. The Local Authorities Elections Ordinance was introduced in 1946 to provide for the conduct of elections to Local bodies. The Department of Parliamentary Elections functioned under a Commissioner to register voters and to conduct Parliamentary elections and the Department of Local Government Elections functioned under a Commissioner to conduct Local Government elections. The “Department of Elections” was established on 01st of October 1955 amalgamating the Department of Parliamentary Elections and the Department of Local Government Elections. -

Diverse Genetic Origin of Indian Muslims: Evidence from Autosomal STR Loci

Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 54, 340–348 & 2009 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diverse genetic origin of Indian Muslims: evidence from autosomal STR loci Muthukrishnan Eaaswarkhanth1,2, Bhawna Dubey1, Poorlin Ramakodi Meganathan1, Zeinab Ravesh2, Faizan Ahmed Khan3, Lalji Singh2, Kumarasamy Thangaraj2 and Ikramul Haque1 The origin and relationships of Indian Muslims is still dubious and are not yet genetically well studied. In the light of historically attested movements into Indian subcontinent during the demic expansion of Islam, the present study aims to substantiate whether it had been accompanied by any gene flow or only a cultural transformation phenomenon. An array of 13 autosomal STR markers that are common in the worldwide data sets was used to explore the genetic diversity of Indian Muslims. The austere endogamy being practiced for several generations was confirmed by the genetic demarcation of each of the six Indian Muslim communities in the phylogenetic assessments for the markers examined. The analyses were further refined by comparison with geographically closest neighboring Hindu religious groups (including several caste and tribal populations) and the populations from Middle East, East Asia and Europe. We found that some of the Muslim populations displayed high level of regional genetic affinity rather than religious affinity. Interestingly, in Dawoodi Bohras (TN and GUJ) and Iranian Shia significant genetic contribution from West Asia, especially Iran (49, 47 and 46%, respectively) was observed. This divulges the existence of Middle Eastern genetic signatures in some of the contemporary Indian Muslim populations. -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

The Case of Sri Lanka Administrative Service

Entrepreneurship in Public Management: The Case of Sri Lanka Administrative Service Lalitha Fernando, University of Sri Jayawerdenepura, Sri Lanka Abstract. The role of entrepreneurship in public management remains in debate. Despite the debatable arguments to regarding public entrepreneurship, this paper argues that the concept still has validity of utilizing as a tool for improving the effectiveness and efficiency of public service. By using Hunter’s reputational snowballing technique to identify public entrepreneurs among Sri Lanka’s administrative service, this study presents the preliminary findings based on a recent empirical study and examines their administrative and decision-making roles towards desired changes in the public service in Sri Lanka. During the period of October 2002 and March 2003, the study gathered the data through in-depth interviews of 25 officers in the Sri Lanka Administrative Service. The results of the study indicate that public managers’ motivation to achieve and their leadership skills, goal clarity, managerial autonomy, performance-based reward system, citizen participation and public support represent major factors contributing to public entrepreneurship in the Sri Lanka Administrative Service. This study also finds that there are entrepreneurs in the Sri Lanka public service. Also the paper argues that there are opportunities and potential in the service to work as entrepreneurs who are innovative, proactive and willing to take some risks beyond their work responsibilities. Further, the author argues that there are significant benefits when the entrepreneurship is applied to public management. Therefore the necessary reforms are needed to sustain such initiatives of public entrepreneurs towards more effectiveness and efficiency of public service. -

Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78)

FAMINE, DISEASE, MEDICINE AND THE STATE IN MADRAS PRESIDENCY (1876-78). LEELA SAMI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: U5922B8 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592238 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION OF NUMBER OF WORDS FOR MPHIL AND PHD THESES This form should be signed by the candidate’s Supervisor and returned to the University with the theses. Name of Candidate: Leela Sami ThesisTitle: Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78) College: Unversity College London I confirm that the following thesis does not exceed*: 100,000 words (PhD thesis) Approximate Word Length: 100,000 words Signed....... ... Date ° Candidate Signed .......... .Date. Supervisor The maximum length of a thesis shall be for an MPhil degree 60,000 and for a PhD degree 100,000 words inclusive of footnotes, tables and figures, but exclusive of bibliography and appendices. Please note that supporting data may be placed in an appendix but this data must not be essential to the argument of the thesis. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

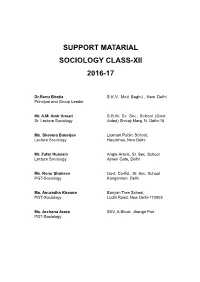

Support Matarial Sociology Class-Xii 2016-17

SUPPORT MATARIAL SOCIOLOGY CLASS-XII 2016-17 Dr.Renu Bhatia S.K.V. Moti Bagh-I, New Delhi Principal and Group Leader Mr. A.M. Amir Ansari S.B.M. Sr. Sec. School (Govt. Sr. Lecture Sociology Aided) Shivaji Marg, N. Delhi-15 Ms. Sheema Banerjee Laxman Public School, Lecture Sociology Hauzkhas, New Delhi Mr. Zafar Hussain Anglo-Aravic, Sr. Sec. School Lecture Sociology Ajmeri Gate, Delhi Ms. Renu Shokeen Govt. Co-Ed., Sr. Sec. School PGT-Sociology Kanganheri, Delhi Ms. Anuradha Khanna Banyan Tree School, PGT-Sociology Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Ms. Archana Arora SKV, A-Block, Jhangir Puri PGT-Sociology SOCIOLOGY (CODE NO.039) CLASS XII (2015-16) One Paper Theroy Marks 80 Unitwise Weightage 3 hours Units Periods Marks A Indian Society 1. Introducing Indian Society 10 32 2. Demographic Structure and Indain Society 10 Chapter-1 3. Social Institutions-Continuity and Change 12 and 4. Market as a Social Institution. 10 Chapter 7 5. Pattern of social Inequality and Exclusion 20 are non- 6. Challenges of Cultural Diversity 16 evaluative 7. Suggestions for Project Work 16 B Change and Developmentin Indian Society 8. Structural Change 10 9. Cultural Chage 12 10. The Story of Democaracy 18 Class XII - Sociology 2 11. Change and Development in Rural Society 10 48 12. Change and Development in industrial Society14 13. Globalization and Social Change 10 14. Mass Media and Communication 14 15. Social Movements 18 200 48 3 Class XII - Sociology BOOK I CHAPTER 2 THE DEMOGRAPCHIC STRUCTURE OF THE INDIAN SOCIETY KEY POINTS 1. Demography Demography, a systematic study of population, is a Greek term derived form two words, ‘demos’ (people) and graphein (describe) description of people. -

The Political Aco3mxddati0n of Primqpjdial Parties

THE POLITICAL ACO3MXDDATI0N OF PRIMQPJDIAL PARTIES DMK (India) and PAS (Malaysia) , by Y. Mansoor Marican M.Soc.Sci. (S'pore), 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FL^iDlMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of. Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforniing to the required standard THE IJNT^RSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November. 1976 ® Y. Mansoor Marican, 1976. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of POLITICAL SCIENCE The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ABSTRACT This study is rooted in a theoretical interest in the development of parties that appeal mainly to primordial ties. The claims of social relationships based on tribe, race, language or religion have the capacity to rival the civil order of the state for the loyalty of its citizens, thus threatening to undermine its political authority. This phenomenon is endemic to most Asian and African states. Most previous research has argued that political competition in such contexts encourages the formation of primordially based parties whose activities threaten the integrity of these states. -

CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of TAMILNADU Entry No

CENTRAL LIST OF OBC FOR THE STATE OF TAMILNADU E C/Cmm Rsoluti No. & da N. Agamudayar including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 1 Thozhu or Thuluva Vellala Alwar, -do- Azhavar and Alavar 2 (in Kanniyakumari district and Sheoncottah Taulk of Tirunelveli district ) Ambalakarar, -do- 3 Ambalakaran 4 Andi pandaram -do- Arayar, -do- Arayan, 5 Nulayar (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) 6 Archakari Vellala -do- Aryavathi -do- 7 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) Attur Kilnad Koravar (in Salem, South 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Arcot, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 8 Ramanathapuram Kamarajar and Pasumpon Muthuramadigam district) 9 Attur Melnad Koravar (in Salem district) -do- 10 Badagar -do- Bestha -do- 11 Siviar 12 Bhatraju (other than Kshatriya Raju) -do- 13 Billava -do- 14 Bondil -do- 15 Boyar -do- Oddar (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Boya, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Donga Boya, Gorrela Dodda Boya Kalvathila Boya, 16 Pedda Boya, Oddar, Kal Oddar Nellorepet Oddar and Sooramari Oddar) 17 Chakkala -do- Changayampadi -do- 18 Koravar (In North Arcot District) Chavalakarar 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 19 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 taluk of Tirunelveli district) Chettu or Chetty (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Kottar Chetty, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Elur Chetty, Pathira Chetty 20 Valayal Chetty Pudukkadai Chetty) (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) C.K. -

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: the ROOTS of PLURALISM BREAKDOWN

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: THE ROOTS OF PLURALISM BREAKDOWN Neil DeVotta | Wake Forest University April 2017 I. INTRODUCTION when seeking power; and the sectarian violence that congealed and hardened attitudes over time Sri Lanka represents a classic case of a country all contributed to majoritarianism. Multiple degenerating on the ethnic and political fronts issues including colonialism, a sense of Sinhalese when pluralism is deliberately eschewed. At Buddhist entitlement rooted in mytho-history, independence in 1948, Sinhalese elites fully economic grievances, politics, nationalism and understood that marginalizing the Tamil minority communal violence all interacting with and was bound to cause this territorialized community stemming from each other, pushed the island to eventually hit back, but they succumbed to towards majoritarianism. This, in turn, then led to ethnocentrism and majoritarianism anyway.1 ethnic riots, a civil war accompanied by terrorism What were the factors that motivated them to do that ultimately killed over 100,000 people, so? There is no single explanation for why Sri democratic regression, accusations of war crimes Lanka failed to embrace pluralism: a Buddhist and authoritarianism. revival in reaction to colonialism that allowed Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists to combine their The new government led by President community’s socio-economic grievances with Maithripala Sirisena, which came to power in ethnic and religious identities; the absence of January 2015, has managed to extricate itself minority guarantees in the Constitution, based from this authoritarianism and is now trying to on the Soulbury Commission the British set up revive democratic institutions promoting good prior to granting the island independence; political governance and a degree of pluralism. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & Unreached People

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) AGWM Western edition I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

Sri Lanka: Political-Military Relations

Working Paper Series Working Paper 3 Sri Lanka: Political-Military Relations K.M. de Silva Conflict Research Unit Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ November 2001 Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague Phonenumber: # 31-70-3245384 Telefax: # 31-70-3282002 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/cru © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. © The Clingendael Institute 3 Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 The Armed Services in a Period of Change: 1946-1966 7 3 The Military Confronts Armed Rebels: 1971-1977 11 4 Militarisation and Ethnic Conflict: 1977-2000 13 5 The Current Situation: 2000 19 Critical Bibliography 23 4 © The Clingendael Institute © The Clingendael Institute 5 Introduction1 There is an amazing variety of policies and experiences in civil-military relations in the successor states of the British raj and the empire in South Asia. Sri Lanka was not part of the raj, and always had a more civilian- oriented government system under colonial rule. Like India, Sri Lanka too has had a long and virtually unbroken tradition of democratic rule since independence; both countries have had an unbroken record of subordination of the military to the civil authority. Unlike in India, Sri Lanka has had two abortive coup attempts in 1962 and 1966.