Here Caste Is Lived and Experienced, the Paper Finds the Holds Are Grouped Using Conventional, Government-Defined Relationships to Be Far More Varied and Nuanced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diverse Genetic Origin of Indian Muslims: Evidence from Autosomal STR Loci

Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 54, 340–348 & 2009 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diverse genetic origin of Indian Muslims: evidence from autosomal STR loci Muthukrishnan Eaaswarkhanth1,2, Bhawna Dubey1, Poorlin Ramakodi Meganathan1, Zeinab Ravesh2, Faizan Ahmed Khan3, Lalji Singh2, Kumarasamy Thangaraj2 and Ikramul Haque1 The origin and relationships of Indian Muslims is still dubious and are not yet genetically well studied. In the light of historically attested movements into Indian subcontinent during the demic expansion of Islam, the present study aims to substantiate whether it had been accompanied by any gene flow or only a cultural transformation phenomenon. An array of 13 autosomal STR markers that are common in the worldwide data sets was used to explore the genetic diversity of Indian Muslims. The austere endogamy being practiced for several generations was confirmed by the genetic demarcation of each of the six Indian Muslim communities in the phylogenetic assessments for the markers examined. The analyses were further refined by comparison with geographically closest neighboring Hindu religious groups (including several caste and tribal populations) and the populations from Middle East, East Asia and Europe. We found that some of the Muslim populations displayed high level of regional genetic affinity rather than religious affinity. Interestingly, in Dawoodi Bohras (TN and GUJ) and Iranian Shia significant genetic contribution from West Asia, especially Iran (49, 47 and 46%, respectively) was observed. This divulges the existence of Middle Eastern genetic signatures in some of the contemporary Indian Muslim populations. -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78)

FAMINE, DISEASE, MEDICINE AND THE STATE IN MADRAS PRESIDENCY (1876-78). LEELA SAMI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: U5922B8 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592238 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION OF NUMBER OF WORDS FOR MPHIL AND PHD THESES This form should be signed by the candidate’s Supervisor and returned to the University with the theses. Name of Candidate: Leela Sami ThesisTitle: Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78) College: Unversity College London I confirm that the following thesis does not exceed*: 100,000 words (PhD thesis) Approximate Word Length: 100,000 words Signed....... ... Date ° Candidate Signed .......... .Date. Supervisor The maximum length of a thesis shall be for an MPhil degree 60,000 and for a PhD degree 100,000 words inclusive of footnotes, tables and figures, but exclusive of bibliography and appendices. Please note that supporting data may be placed in an appendix but this data must not be essential to the argument of the thesis. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

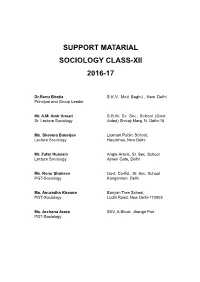

Support Matarial Sociology Class-Xii 2016-17

SUPPORT MATARIAL SOCIOLOGY CLASS-XII 2016-17 Dr.Renu Bhatia S.K.V. Moti Bagh-I, New Delhi Principal and Group Leader Mr. A.M. Amir Ansari S.B.M. Sr. Sec. School (Govt. Sr. Lecture Sociology Aided) Shivaji Marg, N. Delhi-15 Ms. Sheema Banerjee Laxman Public School, Lecture Sociology Hauzkhas, New Delhi Mr. Zafar Hussain Anglo-Aravic, Sr. Sec. School Lecture Sociology Ajmeri Gate, Delhi Ms. Renu Shokeen Govt. Co-Ed., Sr. Sec. School PGT-Sociology Kanganheri, Delhi Ms. Anuradha Khanna Banyan Tree School, PGT-Sociology Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Ms. Archana Arora SKV, A-Block, Jhangir Puri PGT-Sociology SOCIOLOGY (CODE NO.039) CLASS XII (2015-16) One Paper Theroy Marks 80 Unitwise Weightage 3 hours Units Periods Marks A Indian Society 1. Introducing Indian Society 10 32 2. Demographic Structure and Indain Society 10 Chapter-1 3. Social Institutions-Continuity and Change 12 and 4. Market as a Social Institution. 10 Chapter 7 5. Pattern of social Inequality and Exclusion 20 are non- 6. Challenges of Cultural Diversity 16 evaluative 7. Suggestions for Project Work 16 B Change and Developmentin Indian Society 8. Structural Change 10 9. Cultural Chage 12 10. The Story of Democaracy 18 Class XII - Sociology 2 11. Change and Development in Rural Society 10 48 12. Change and Development in industrial Society14 13. Globalization and Social Change 10 14. Mass Media and Communication 14 15. Social Movements 18 200 48 3 Class XII - Sociology BOOK I CHAPTER 2 THE DEMOGRAPCHIC STRUCTURE OF THE INDIAN SOCIETY KEY POINTS 1. Demography Demography, a systematic study of population, is a Greek term derived form two words, ‘demos’ (people) and graphein (describe) description of people. -

The Political Aco3mxddati0n of Primqpjdial Parties

THE POLITICAL ACO3MXDDATI0N OF PRIMQPJDIAL PARTIES DMK (India) and PAS (Malaysia) , by Y. Mansoor Marican M.Soc.Sci. (S'pore), 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FL^iDlMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of. Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforniing to the required standard THE IJNT^RSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November. 1976 ® Y. Mansoor Marican, 1976. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of POLITICAL SCIENCE The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ABSTRACT This study is rooted in a theoretical interest in the development of parties that appeal mainly to primordial ties. The claims of social relationships based on tribe, race, language or religion have the capacity to rival the civil order of the state for the loyalty of its citizens, thus threatening to undermine its political authority. This phenomenon is endemic to most Asian and African states. Most previous research has argued that political competition in such contexts encourages the formation of primordially based parties whose activities threaten the integrity of these states. -

CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of TAMILNADU Entry No

CENTRAL LIST OF OBC FOR THE STATE OF TAMILNADU E C/Cmm Rsoluti No. & da N. Agamudayar including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 1 Thozhu or Thuluva Vellala Alwar, -do- Azhavar and Alavar 2 (in Kanniyakumari district and Sheoncottah Taulk of Tirunelveli district ) Ambalakarar, -do- 3 Ambalakaran 4 Andi pandaram -do- Arayar, -do- Arayan, 5 Nulayar (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) 6 Archakari Vellala -do- Aryavathi -do- 7 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) Attur Kilnad Koravar (in Salem, South 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Arcot, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 8 Ramanathapuram Kamarajar and Pasumpon Muthuramadigam district) 9 Attur Melnad Koravar (in Salem district) -do- 10 Badagar -do- Bestha -do- 11 Siviar 12 Bhatraju (other than Kshatriya Raju) -do- 13 Billava -do- 14 Bondil -do- 15 Boyar -do- Oddar (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Boya, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Donga Boya, Gorrela Dodda Boya Kalvathila Boya, 16 Pedda Boya, Oddar, Kal Oddar Nellorepet Oddar and Sooramari Oddar) 17 Chakkala -do- Changayampadi -do- 18 Koravar (In North Arcot District) Chavalakarar 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 19 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 taluk of Tirunelveli district) Chettu or Chetty (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Kottar Chetty, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Elur Chetty, Pathira Chetty 20 Valayal Chetty Pudukkadai Chetty) (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) C.K. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & Unreached People

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) AGWM Western edition I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

HIGH COURT of JUDICATURE at MADRAS FRIDAY 28 AUGUST 2020 INDEX Sl

. HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS FRIDAY 28 AUGUST 2020 INDEX Sl. Video Conference Sitting Arrangements / Coram Pages No. Court 1 NOTIFICATION NO. 183 / 2020 1 CHIEF JUSTICE & 2 VC 01 2 - 8 SENTHILKUMAR RAMAMOORTHY.J VINEET KOTHARI.J & 3 VC 02 9 - 10 KRISHNAN RAMASAMY.J R.SUBBIAH.J & 4 VC 03 11 - 16 C.SARAVANAN.J R.SUBBIAH.J & 5 VC 03 17 C.SARAVANAN.J N.KIRUBAKARAN.J & 6 VC 05 18 - 21 V.M.VELUMANI.J M.M.SUNDRESH.J & 7 VC 06 22 - 28 R.HEMALATHA.J T.S.SIVAGNANAM.J & 8 VC 07 29 - 31 PUSHPA SATHYANARAYANA.J 9 VC 08 M.DURAISWAMY.J 32 - 34 10 VC 09 T.RAJA.J 35 - 37 11 VC10 K.RAVICHANDRABAABU.J 38 - 42 12 VC 11 P.N.PRAKASH.J 43 - 45 13 VC 12 PUSHPA SATHYANARAYANA.J 46 - 47 14 VC 12 PUSHPA SATHYANARAYANA.J (Advance List) 48 - 57 15 VC 15 R.MAHADEVAN.J 58 - 70 16 VC 16 V.M.VELUMANI.J 71 - 72 17 VC 20 V.PARTHIBAN.J 73 - 81 18 VC 21 R.SUBRAMANIAN.J 82 - 85 19 VC 22 M.GOVINDARAJ.J 86 - 89 20 VC 23 M.SUNDAR.J (OS) 90 - 94 21 VC 26 M.S.RAMESH.J 95 - 103 22 VC 27 S.M.SUBRAMANIAM.J 104 - 107 23 VC 27 S.M.SUBRAMANIAM.J 108 - 110 24 VC 28 ANITA SUMANTH.J 111 - 120 25 VC 29 T.RAVINDRAN.J 121 - 122 26 VC 30 P.VELMURUGAN.J 123 - 126 27 VC 31 G.JAYACHANDRAN.J 127 - 129 28 VC 31 G.JAYACHANDRAN.J 130 - 133 29 VC 34 N.SATHISH KUMAR.J (OS) 134 - 142 30 VC 37 A.D.JAGADISH CHANDIRA.J 143 - 151 31 VC 39 ABDUL QUDDHOSE.J 152 - 157 32 VC 40 M.DHANDAPANI.J 158 - 161 33 VC 41 P.D.AUDIKESAVALU.J 162 - 165 34 VC 47 P.T.ASHA.J (OS) 166 - 174 35 VC 47 P.T.ASHA.J (Advance List for 31.08.2020) (OS) 175 - 179 36 VC 48 M.NIRMAL KUMAR.J 180 37 VC 48 M.NIRMAL KUMAR.J 181 - 184 38 VC 49 N.ANAND VENKATESH.J 185 - 193 39 VC 49 N.ANAND VENKATESH.J 194 - 195 40 VC 50 G.K.ILANTHIRAIYAN.J 196 - 200 41 VC 52 C.SARAVANAN.J 201 - 203 42 PROVISIONAL LIST 204 - 214 43 VC MC MASTER COURT 215 NOTIFICATION NO. -

The Titles of Vanniya Kulakshatriyas – a Study

DOI: 10.15613/hijrh/2017/v4i1/154514 ISSN (Print): 2349-4778 HuSS: International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol 4(1), 22–25, January–June 2017 ISSN (Online): 2349-8900 The Titles of Vanniya Kulakshatriyas – A Study R. Anuradha* Assistant Professor, Department of History, Sri Sarada College for Women (Autonomous), Salem, Tamil Nadu, India; [email protected] Abstract The Vanniyars are basically considered to be the people belonging to the community of the ruling class of great Indian sub- continent for many centuries. Most Vanniyars in India are in the three adjacent southern states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andra Pradesh, mostly concentrated in the area where these three states intersect. The term Vanniyars (Vanniyans) and Padayatchi has been used interchangeably because of the same historical origin they claim. Among the castes in the Tamil Nadu, Vanniyars or Padayatchis are very popular and they are one of the very earliest caste to be socially well organized. Today they are the most politically mobilized and well-informed caste in Tamil Nadu. Many Vanniyars migrated to South Africa, Malaysia, Singapore, Seychelles, Mauritius and Fiji and the next generation Vanniyars have been using variant titles such as Goundar, Naicker and Padayatchi amongst themselves. Keywords: Goundar, Palli, Padayachi, Vanniyar, Vellalas 1. Introduction analyzing the 2000 year old history of the Vanniyar race it can be noted that the people belonging to this race have The word Vanni in Sanskrit means fire and from one of been living in Tamil Nadu as Vanniyar Kula Kshatriyar, the legends of Vanniyars it is mentioned that Lord Shiva in Andhra as Agni Kula Kshatriyar and in Karnataka as accepted the prayer and Yagna of the Sambu Muniver and Sambukula Kshatriyar3. -

Mapping Research in Gender and Digital Technology

MAPPING RESEARCH IN GENDER AND DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY january 2018 Authors Main editor Anri van der Spuy Namita Aavriti Namita Aavriti Copy editing and proofreading Additional inputs Lori Nordstrom (APC) Chenai Chair Nitya V Dafne Sabanes Plou Kaitlyn Wauthier Publication production Radhika Gajjala Cathy Chen (APC) Smita Vanniyar Yara Sallam Cover collage Flavia Fascendini Additional contributions to the GenderIT.org edition: Mapping gaps Infographic visuals in research in gender and information society Cathy Chen (APC) Carmen Alcazar Elena Pavan Ghadeer Ahmed Kerieva McCormick Layout and design Koliwe Majama Monocromo Maria Florencia Alcaraz Neo Musangi Mapping research in gender and digital technology Smita Patil Published by APC 2017 Peer reviewers Jac sm Kee Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- Katerina Fialova ShareAlike 3.0 license Ruhiya Seward ISBN 978-92-95102-98-9 APC-201801-APC-R-EN-DIGITAL-288 Reviewers at Expert Group Meeting Anonymous (Middle East North Africa) Becky Faith Bruna Zanolli Caitlin Bentley Catalina Alzate Chenai Chair Elena Pavan Horacio F. Sívori Jennifer Radloff Jinnie Chae Kalyani Menon-Sen Mariana Giorgetti Valente Matthew Smith Patricia Peña Ruth Nyambura Kilonzo Safa Khan Tigist Shewarega Hussen This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of IDRC or its Board of Governors. International Development Research Centre Centre de recherches pour le développement international Standards for use of the IDRC logo and Canada wordmark October 2014 This research is part of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) project “Mapping gender and digital technology”, funded by the International Development Research Centre. -

Population Differentiation of Southern Indian Male Lineages Correlates with Agricultural Expansions Predating the Caste System

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Anthropology Papers Department of Anthropology 11-28-2012 Population Differentiation of Southern Indian Male Lineages Correlates With Agricultural Expansions Predating the Caste System GaneshPrasad ArunKumar David F. Soria-Hernanz Valampuri John Kavitha Varatharajan Santhakumari Arun Adhikarla Syama See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation ArunKumar, G., Soria-Hernanz, D. F., Kavitha, V., Arun, V., Syama, A., Ashokan, K., Gandhirajan, K., Vijayakumar, K., Narayanan, M., Jayalakshmi, M., Ziegle, J. S., Royyuru, A. K., Parida, L., Wells, R., Renfrew, C., Schurr, T. G., Tyler Smith, C., Platt, D. E., Pitchappan, R., & Genographic Consortium (2012). Population Differentiation of Southern Indian Male Lineages Correlates With Agricultural Expansions Predating the Caste System. PLoS One, 7 (11), e50269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050269 The full list of Genographic Consortium members can be found in the Acknowledgements. Correction: Some of the values in Table 2 were included in the wrong columns. Please see the correct version of Table 2 at the following link: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/annotation/8663819b-5ff0-4133-b70a-2d686dfb0a44 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/44 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Population Differentiation of Southern Indian Male Lineages Correlates With Agricultural Expansions Predating the Caste System Abstract Previous studies that pooled Indian populations from a wide variety of geographical locations, have obtained contradictory conclusions about the processes of the establishment of the Varna caste system and its genetic impact on the origins and demographic histories of Indian populations.