Mapping Research in Gender and Digital Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Content Regulation in the Digital

Content Regulation in the Digital Age Submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression by the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) February 2018 Introduction 1 I. Company compliance with State laws 2 Terrorism-related and extremist content 3 False news, disinformation and propaganda 4 The “right to be forgotten” framework? 7 How should companies respond to State content regulation laws and measures that may be inconsistent with international human rights standards? 8 II. Other State Requests 9 State requests based on platform terms of service (ToS) and “shadow” requests 9 Non-transparent agreements with companies 10 III. Global removals 11 IV. Individuals at risk 12 V. Content regulation processes 15 VI. Bias and non-discrimination 16 VII. Appeals and remedies 17 VIII. Automation and content moderation 17 IX. Transparency 18 X. General recommendations from APC 19 Introduction The Association for Progressive Communications (APC) is an international network and non- profit organisation founded in 1990 that works to help ensure everyone has affordable access to a free and open internet to improve lives, realise human rights and create a more just world. We welcome this topic because it is current and integral to our work. On the one hand there is a lot of ‘noise’ in the mainstream media about so-called “fake news” and what appears to be a fairly rushed response from platforms consisting of increasing in-house regulation of content. On the other hand, human rights defenders and activists we work with express concern that 1 platforms are removing some of their content in a manner that suggests political bias and reinforcing of societal discrimination. -

Diverse Genetic Origin of Indian Muslims: Evidence from Autosomal STR Loci

Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 54, 340–348 & 2009 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diverse genetic origin of Indian Muslims: evidence from autosomal STR loci Muthukrishnan Eaaswarkhanth1,2, Bhawna Dubey1, Poorlin Ramakodi Meganathan1, Zeinab Ravesh2, Faizan Ahmed Khan3, Lalji Singh2, Kumarasamy Thangaraj2 and Ikramul Haque1 The origin and relationships of Indian Muslims is still dubious and are not yet genetically well studied. In the light of historically attested movements into Indian subcontinent during the demic expansion of Islam, the present study aims to substantiate whether it had been accompanied by any gene flow or only a cultural transformation phenomenon. An array of 13 autosomal STR markers that are common in the worldwide data sets was used to explore the genetic diversity of Indian Muslims. The austere endogamy being practiced for several generations was confirmed by the genetic demarcation of each of the six Indian Muslim communities in the phylogenetic assessments for the markers examined. The analyses were further refined by comparison with geographically closest neighboring Hindu religious groups (including several caste and tribal populations) and the populations from Middle East, East Asia and Europe. We found that some of the Muslim populations displayed high level of regional genetic affinity rather than religious affinity. Interestingly, in Dawoodi Bohras (TN and GUJ) and Iranian Shia significant genetic contribution from West Asia, especially Iran (49, 47 and 46%, respectively) was observed. This divulges the existence of Middle Eastern genetic signatures in some of the contemporary Indian Muslim populations. -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

Claiming and Reclaiming the Digital World As a Public Space

Claiming and Reclaiming the Digital World as a Public Space Experiences and insights from feminists in the Middle East and North Africa www.oxfam.org OXFAM DISCUSSION PAPER – NOVEMBER 2020 This paper seeks to highlight the experiences and aspirations of young women and feminist activists in the MENA region around digital spaces, safety and rights. It explores individual women’s experiences engaging with the digital world, the opportunities and challenges that women’s rights and feminist organizations find in these platforms, and the digital world as a space of resistance, despite restrictions on civic space. Drawing on interviews with feminist activists from the region, the paper sheds light on women’s online experiences and related offline risks, and illustrates patterns and behaviours that prevailed during the COVID-19 pandemic. © Oxfam International November 2020 This paper was written by Francesca El Asmar. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Hadeel Qazzaz, Manal Wardé, Neus Tirado Gual, Salma Jrad, Joane Cremesty, Suzan Al Ostaz, Fadi Touma and Mounia Semlali in its production, as well as the contributions of the interviewees who participated in the research process. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email [email protected] This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. -

Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78)

FAMINE, DISEASE, MEDICINE AND THE STATE IN MADRAS PRESIDENCY (1876-78). LEELA SAMI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: U5922B8 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592238 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION OF NUMBER OF WORDS FOR MPHIL AND PHD THESES This form should be signed by the candidate’s Supervisor and returned to the University with the theses. Name of Candidate: Leela Sami ThesisTitle: Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78) College: Unversity College London I confirm that the following thesis does not exceed*: 100,000 words (PhD thesis) Approximate Word Length: 100,000 words Signed....... ... Date ° Candidate Signed .......... .Date. Supervisor The maximum length of a thesis shall be for an MPhil degree 60,000 and for a PhD degree 100,000 words inclusive of footnotes, tables and figures, but exclusive of bibliography and appendices. Please note that supporting data may be placed in an appendix but this data must not be essential to the argument of the thesis. -

Intellectual Privacy and Censorship of the Internet

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 1998 Intellectual Privacy and Censorship of the Internet Julie E. Cohen Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1963 8 Seton Hall Const. L.J. 693 (1997-1998) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons 1998 INTERNET SYMPOSIUM INTELLECTUAL PRIVACY AND CENSORSHIP OF THE INTERNET ProfessorJulie E. Cohen Good morning. I would like to thank the Constitutional Law Journal for inviting me to be here today. I am not a First Amendment lawyer. I am not really a constitutional law- yer, so why am I here? I think that after having heard Dan Burk's presenta- tion, you should realize that intellectual property lawyers need to be First Amendment lawyers as well. You have all heard the aphorism that the Internet interprets censorship as a malfunction and routes around it.' You also may have heard that censorship on the Internet is a terrible thing; in particular, you may have heard this in the context of debates about pornography on the Inter- net or hate speech on the Internet. I would like to suggest to you today, how- ever, that the single most prevalent problem involving censorship on the Inter- net has to do with the protection of intellectual property. If you think about it, intellectual property protection, and particularly copy- right protection, is a form of censorship. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

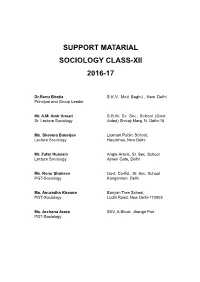

Support Matarial Sociology Class-Xii 2016-17

SUPPORT MATARIAL SOCIOLOGY CLASS-XII 2016-17 Dr.Renu Bhatia S.K.V. Moti Bagh-I, New Delhi Principal and Group Leader Mr. A.M. Amir Ansari S.B.M. Sr. Sec. School (Govt. Sr. Lecture Sociology Aided) Shivaji Marg, N. Delhi-15 Ms. Sheema Banerjee Laxman Public School, Lecture Sociology Hauzkhas, New Delhi Mr. Zafar Hussain Anglo-Aravic, Sr. Sec. School Lecture Sociology Ajmeri Gate, Delhi Ms. Renu Shokeen Govt. Co-Ed., Sr. Sec. School PGT-Sociology Kanganheri, Delhi Ms. Anuradha Khanna Banyan Tree School, PGT-Sociology Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Ms. Archana Arora SKV, A-Block, Jhangir Puri PGT-Sociology SOCIOLOGY (CODE NO.039) CLASS XII (2015-16) One Paper Theroy Marks 80 Unitwise Weightage 3 hours Units Periods Marks A Indian Society 1. Introducing Indian Society 10 32 2. Demographic Structure and Indain Society 10 Chapter-1 3. Social Institutions-Continuity and Change 12 and 4. Market as a Social Institution. 10 Chapter 7 5. Pattern of social Inequality and Exclusion 20 are non- 6. Challenges of Cultural Diversity 16 evaluative 7. Suggestions for Project Work 16 B Change and Developmentin Indian Society 8. Structural Change 10 9. Cultural Chage 12 10. The Story of Democaracy 18 Class XII - Sociology 2 11. Change and Development in Rural Society 10 48 12. Change and Development in industrial Society14 13. Globalization and Social Change 10 14. Mass Media and Communication 14 15. Social Movements 18 200 48 3 Class XII - Sociology BOOK I CHAPTER 2 THE DEMOGRAPCHIC STRUCTURE OF THE INDIAN SOCIETY KEY POINTS 1. Demography Demography, a systematic study of population, is a Greek term derived form two words, ‘demos’ (people) and graphein (describe) description of people. -

The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age

The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age April 9, 2018 Dr. Keith Goldstein, Dr. Ohad Shem Tov, and Mr. Dan Prazeres Presented on behalf of Pirate Parties International Headquarters, a UN ECOSOC Consultative Member, for the Report of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Our Dystopian Present Living in modern society, we are profiled. We accept the necessity to hand over intimate details about ourselves to proper authorities and presume they will keep this information secure- only to be used under the most egregious cases with legal justifications. Parents provide governments with information about their children to obtain necessary services, such as health care. We reciprocate the forfeiture of our intimate details by accepting the fine print on every form we sign- or button we press. In doing so, we enable second-hand trading of our personal information, exponentially increasing the likelihood that our data will be utilized for illegitimate purposes. Often without our awareness or consent, detection devices track our movements, our preferences, and any information they are capable of mining from our digital existence. This data is used to manipulate us, rob from us, and engage in prejudice against us- at times legally. We are stalked by algorithms that profile all of us. This is not a dystopian outlook on the future or paranoia. This is present day reality, whereby we live in a data-driven society with ubiquitous corruption that enables a small number of individuals to transgress a destitute mass of phone and internet media users. In this paper we present a few examples from around the world of both violations of privacy and accomplishments to protect privacy in online environments. -

Annual Report 2017

101110101011101101010011100101110101011101101010011100 10111010101110110101001 10101110001010 EDRi EUROPEAN DIGITAL RIGHTS 110101011101101010011100101011101101010011100101 10101110110101000010010100EUROPEAN010 DIGITAL001 RIGHTS11011101110101011101101100000100101101000 DEFENDING RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS ONLINE 01000111011101110101 101011101101010000100101000100011101110111010101110110110000010010110100001000111011101110101 101110101010011100 101110101011101101010011100 101011101101010000100101000100011101 101011101101010000100101000100011101110111010101110110110000010010110100001000111011101110101 101110101010011100 101110101011101101010011100 1010111011010100001001010001000111011101110101011101101100000 101011101101010000100101000100011101110111010101110110110000010010110100001000111011101110101 101110101010011100 101110101011101101010011100 10101110110101000010010100010001110111011101010111011011000001001011010000100011101110111010 101011101101010000100101000100011101110111010101110110110000010010110100001000111011101110101 101110101010011100 101110101011101101010011100 101011101101010000100101000100011101110111010101110110110000010010110100001000111011101110101 101110101010011100 101110101011101101010011100 EUROPEAN DIGITAL RIGHTS EUROPEAN DIGITAL RIGHTS ANNUAL REPORT 2017 1011011101101110111010111011111011 January 2017 – December 2017 1011011101101110111011101100110111 101011101101010000100101000100011101110111010101110110110000010010110100001000111011101110101 101110101010011100 101110101011101101010011100 101011101101010000100101000100011101110111010101110110110000010010110100001000111011101110101 -

The Political Aco3mxddati0n of Primqpjdial Parties

THE POLITICAL ACO3MXDDATI0N OF PRIMQPJDIAL PARTIES DMK (India) and PAS (Malaysia) , by Y. Mansoor Marican M.Soc.Sci. (S'pore), 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FL^iDlMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of. Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforniing to the required standard THE IJNT^RSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November. 1976 ® Y. Mansoor Marican, 1976. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of POLITICAL SCIENCE The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ABSTRACT This study is rooted in a theoretical interest in the development of parties that appeal mainly to primordial ties. The claims of social relationships based on tribe, race, language or religion have the capacity to rival the civil order of the state for the loyalty of its citizens, thus threatening to undermine its political authority. This phenomenon is endemic to most Asian and African states. Most previous research has argued that political competition in such contexts encourages the formation of primordially based parties whose activities threaten the integrity of these states. -

00047-82167.Pdf (548.01

CYVA Research Corporation Abstract Data Slave Trade An Argument for the Abolition of Digital Slavery: The Intrusive & Coercive Collection and Trafficking Of Personal Information for Profit and Power For a Better Union of Social, Economic and Political Liberty, Justice and Prosperity Recognize and Secure the Mutual Rights & Responsibilities of Human-digital Existence Contact: Kevin O’Neil Chairman & CEO 858 793 8100 [email protected] This Abstract (“Abstract”) and the contents herein are owned by CYVA Research Corporation (“CYVA”, “we”, “our”, “us”, or the “Company”) and are being furnished solely for informational purposes. The information contained herein is intended to assist interested parties in making their own evaluations of CYVA. This Abstract does not purport to contain all information that a prospective investor might need or desire in properly evaluating the Company. In all cases, interested parties should conduct their own investigation and analysis of the Company. By accepting this Abstract, each recipient agrees to keep confidential the information contained herein or made available in connection with further investigation of the Company. Each recipient agrees not to reproduce or disclose any such information, in whole or part, to any individual or entity, without the prior written consent of the Company. DRAFT Abstract DRAFT Table of Contents Document Audience, Structure and Purpose 4 Preface 5 Slave Trade Metaphor 5 Network Community 6 1. Introduction: The Data Slave Trade 7 1.1. Our Human Dignity - What Dignity? 7 1.2. Data Protection Laws: Unending Catch-up Game 8 1.3. Awakening: Informational Self-determination 8 1.4. Privacy and Human Dignity Taking a Back Seat to Profits and Power: Recognition and Resistance 9 1.5.