Contemporary Chinese Calligraphy Between Tradition and Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

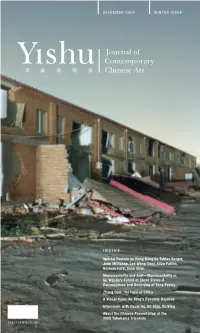

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

The Origins of the Underline As Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: a Case Study in Skeuomorphism

The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Romano, John J. 2016. The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797379 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism John J Romano A Thesis in the Field of Visual Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 Abstract This thesis investigates the process by which the underline came to be used as the default signifier of hyperlinks on the World Wide Web. Created in 1990 by Tim Berners- Lee, the web quickly became the most used hypertext system in the world, and most browsers default to indicating hyperlinks with an underline. To answer the question of why the underline was chosen over competing demarcation techniques, the thesis applies the methods of history of technology and sociology of technology. Before the invention of the web, the underline–also known as the vinculum–was used in many contexts in writing systems; collecting entities together to form a whole and ascribing additional meaning to the content. -

Bluebook Citation in Scholarly Legal Writing

BLUEBOOK CITATION IN SCHOLARLY LEGAL WRITING © 2016 The Writing Center at GULC. All Rights Reserved. The writing assignments you receive in 1L Legal Research and Writing or Legal Practice are primarily practice-based documents such as memoranda and briefs, so your experience using the Bluebook as a first year student has likely been limited to the practitioner style of legal writing. When writing scholarly papers and for your law journal, however, you will need to use the Bluebook’s typeface conventions for law review articles. Although answers to all your citation questions can be found in the Bluebook itself, there are some key, but subtle differences between practitioner writing and scholarly writing you should be careful not to overlook. Your first encounter with law review-style citations will probably be the journal Write-On competition at the end of your first year. This guide may help you in the transition from providing Bluebook citations in court documents to doing the same for law review articles, with a focus on the sources that you are likely to encounter in the Write-On competition. 1. Typeface (Rule 2) Most law reviews use the same typeface style, which includes Ordinary Times New Roman, Italics, and SMALL CAPITALS. In court documents, use Ordinary Roman, Italics, and Underlining. Scholarly Writing In scholarly writing footnotes, use Ordinary Roman type for case names in full citations, including in citation sentences contained in footnotes. This typeface is also used in the main text of a document. Use Italics for the short form of case citations. Use Italics for article titles, introductory signals, procedural phrases in case names, and explanatory signals in citations. -

Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian

Macalester International Volume 18 Chinese Worlds: Multiple Temporalities Article 12 and Transformations Spring 2007 Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian Desheng Fang Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Qian, Zhuzhong and Fang, Desheng (2007) "Towards Chinese Calligraphy," Macalester International: Vol. 18, Article 12. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Chinese Calligraphy Qian Zhuzhong and Fang Desheng I. History of Chinese Calligraphy: A Brief Overview Chinese calligraphy, like script itself, began with hieroglyphs and, over time, has developed various styles and schools, constituting an important part of the national cultural heritage. Chinese scripts are generally divided into five categories: Seal script, Clerical (or Official) script, Regular script, Running script, and Cursive script. What follows is a brief introduction of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy. A. From Prehistory to Xia Dynasty (ca. 16 century B.C.) The art of calligraphy began with the creation of Chinese characters. Without modern technology in ancient times, “Sound couldn’t travel to another place and couldn’t remain, so writings came into being to act as the track of meaning and sound.”1 However, instead of characters, the first calligraphy works were picture-like symbols. These symbols first appeared on ceramic vessels and only showed ambiguous con- cepts without clear meanings. -

The Self-Organization of Contemporary Art in China, 2001–2012

Bao Dong Rethinking Practices within the Art System: The Self-Organization of Contemporary Art in China, 2001–2012 The Origin of the Term “Self-Organization” in China The term “self-organization” was first used in the context of contemporary Chinese art in 2005 at the Second Guangzhou Triennial curated by Hou Hanru, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Guo Xiaoyan. Self-organization was one of the special projects of the triennial, and there were two panel discussions on the topic. The exhibition theme “Beyond” focused on the topic of alternative modernity in China and non-Western countries, and the term self-organization was defined by the following statements: “A number of independent art organizations, institutions, and communities have taken an active role in artistic creation and practice” and “their projects are often diverse, flexible” and “self-induced in nature.”1 Altogether, twenty-four self- organized groups2 were included in this project, and for the curators, the concept of “self-organization” was used to differentiate independent and autonomous organizations from those attached to government systems or political parties. This feature is also the fundamental difference between the various artist-run autonomous organizations and the organizations within the conventional art system as constituted by Chinese Artists Association, along with the various academies of painting, art institutes, museums, and so on. In other words, self-organization is considered a force operating outside of the conventional art system, just as the inception, growth, and flourishing of contemporary Chinese art is believed to have been achieved outside of official systems. In terms of any independence from the conventional art system, self- organization is not a new phenomenon in the contemporary Chinese art scene. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX A Bertsch, Fred, 16 Caslon Italic, 86 accents, 224 Best, Mark, 87 Caslon Openface, 68 Adobe Bickham Script Pro, 30, 208 Betz, Jennifer, 292 Cassandre, A. M., 87 Adobe Caslon Pro, 40 Bézier curve, 281 Cassidy, Brian, 268, 279 Adobe InDesign soft ware, 116, 128, 130, 163, Bible, 6–7 casual scripts typeface design, 44 168, 173, 175, 182, 188, 190, 195, 218 Bickham Script Pro, 43 cave drawing, type development, 3–4 Adobe Minion Pro, 195 Bilardello, Robin, 122 Caxton, 110 Adobe Systems, 20, 29 Binner Gothic, 92 centered type alignment Adobe Text Composer, 173 Birch, 95 formatting, 114–15, 116 Adobe Wood Type Ornaments, 229 bitmapped (screen) fonts, 28–29 horizontal alignment, 168–69 AIDS awareness, 79 Black, Kathleen, 233 Century, 189 Akuin, Vincent, 157 black letter typeface design, 45 Chan, Derek, 132 Alexander Isley, Inc., 138 Black Sabbath, 96 Chantry, Art, 84, 121, 140, 148 Alfon, 71 Blake, Marty, 90, 92, 95, 140, 204 character, glyph compared, 49 alignment block type project, 62–63 character parts, typeface design, 38–39 fi ne-tuning, 167–71 Blok Design, 141 character relationships, kerning, spacing formatting, 114–23 Bodoni, 95, 99 considerations, 187–89 alternate characters, refi nement, 208 Bodoni, Giambattista, 14, 15 Charlemagne, 206 American Type Founders (ATF), 16 boldface, hierarchy and emphasis technique, China, type development, 5 Amnesty International, 246 143 Cholla typeface family, 122 A N D, 150, 225 boustrophedon, Greek alphabet, 5 circle P (sound recording copyright And Atelier, 139 bowl symbol), 223 angled brackets, -

Bingfeng, Dong. "Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art

Bingfeng, Dong. "Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art: In conversation with Tianqi Yu Translated by Hui Miao." China’s iGeneration: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu and Luke Vulpiani. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 73–86. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501300103.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 10:59 UTC. Copyright © Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu, Luke Vulpiani and Contributors 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Cinema of Exhibition: Film in Chinese Contemporary Art Dong Bingfeng In conversation with Tianqi Yu Translated by Hui Miao Dong Bingfeng is regarded as one of the most active curators and art critics working on Chinese contemporary art and visual culture in mainland China today. In the past eight years he has worked at several different contemporary art museums, including the Guangdong Art Museum, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art and Iberia Center for Contemporary Art. At these leading art institutions, he explored the nature and ontology of the ‘moving image’ in its various forms – video art, new media art, video and film installations – pushing the boundaries of the various forms and decon- structing the moving image culture. Currently, Dong is the artistic director at the Li Xianting Film Fund, where he has implemented an intensive exploration into artists’ films shown in gallery spaces, or what has been recently referred to as ‘cinema of exhibition.’ China’s iGeneration co-editor Tianqi Yu interviewed Dong Bingfeng on the emerging field of ‘cinema of exhibition,’ and in the interview Dong shares some of his views on cinema and moving image culture, particularly among China’s current iGeneration. -

September/October 2017 Volume 16, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 VOLUME 16, NUMBER 5 INSI DE 57th Venice Biennale Conversations with Tang Nannan, Liang Yue, Wong Ping Artist Features: Yin Xiuzhen, Fang Tong The April Photography Society US$12.00 NT$350.00 P RINTED IN TA I WAN 6 VOLUME 16, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 C ONT ENT S 28 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 On Continuum and Radical Disruption: The Venice Gathering Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker 14 Continuum—Generation by Generation: The Continuation of Artistic Creation at the 57th Venice Biennale: A Conversation with Tang 47 Nannan Ornella De Nigris 28 What Is the Sound of Failed Aspriations? Samson Young's Songs For Disaster Relief Yeewan Koon 37 Miss Underwater: A Conversation with Liang Yue Alexandra Grimmer 47 Sex in the City: Wong Ping in Conversation Stephanie Bailey 71 65 Yin Xiuzhen’s Fluid Sites of Participation: A Communal Space of Communication and Antagonism Vivian Kuang Sheng 78 The Constructed Reality of Immigrants: Fang Tong’s Contrived Photography Dong Yue Su 86 The April Photography Society: A Re-evaluation of Origins, Artworks, and Aims 87 Adam Monohon 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Wong Ping, The Other Side (detail), 2015, 2-channel video, 8 mins., 2 secs. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue 94 Gallery, Hong Kong. We thank JNBY and Lin Li, Cc Foundation and David Chau, Yin Qing, Chen Ping, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. -

Vol. 123 Style Sheet

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 123 STYLE SHEET The Yale Law Journal follows The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (19th ed. 2010) for citation form and the Chicago Manual of Style (16th ed. 2010) for stylistic matters not addressed by The Bluebook. For the rare situations in which neither of these works covers a particular stylistic matter, we refer to the Government Printing Office (GPO) Style Manual (30th ed. 2008). The Journal’s official reference dictionary is Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. The text of the dictionary is available at www.m-w.com. This Style Sheet codifies Journal-specific guidelines that take precedence over these sources. Rules 1-21 clarify and supplement the citation rules set out in The Bluebook. Rule 22 focuses on recurring matters of style. Rule 1 SR 1.1 String Citations in Textual Sentences 1.1.1 (a)—When parts of a string citation are grammatically integrated into a textual sentence in a footnote (as opposed to being citation clauses or citation sentences grammatically separate from the textual sentence): ● Use semicolons to separate the citations from one another; ● Use an “and” to separate the penultimate and last citations, even where there are only two citations; ● Use textual explanations instead of parenthetical explanations; and ● Do not italicize the signals or the “and.” For example: For further discussion of this issue, see, for example, State v. Gounagias, 153 P. 9, 15 (Wash. 1915), which describes provocation; State v. Stonehouse, 555 P. 772, 779 (Wash. 1907), which lists excuses; and WENDY BROWN & JOHN BLACK, STATES OF INJURY: POWER AND FREEDOM 34 (1995), which examines harm. -

An Intelligent System for Chinese Calligraphy

An Intelligent System for Chinese Calligraphy Songhua Xu†,‡∗, Hao Jiang†,§, Francis C.M. Lau§ and Yunhe Pan†,¶ † CAD & CG State Key Lab of China, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, P.R. China, 310027 ‡ Department of Computer Science, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, 06511 § Department of Computer Science, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, P.R. China ¶ Chinese Academy of Engineering, Beijing, P.R. China, 100088 Abstract if computers can tell the beautiful from what is not, beauty contests could certainly be open to them as well. Such con- tests will probably not feature a catwalking computer, but Our work links Chinese calligraphy to computer science rather computer-generated images of beauty, or these im- through an integrated intelligence approach. We first extract ages against real, human-generated ones. This might be go- strokes of existent calligraphy using a semi-automatic, two- ing overboard, but to imbue the computer with the ability to phase mechanism: the first phase tries to do the best possi- ble extraction using a combination of algorithmic techniques; recognize beauty will likely win general support. Further- the second phase presents an intelligent user interface to al- more, the ultimate intelligent machine in people’s mind is low the user to provide input to the extraction process for one that can create results of beauty on its own, which cer- the difficult cases such as those in highly random, cursive, tainly represents a nice challenge for AI researchers. or distorted styles. Having derived a parametric representa- tion of calligraphy, we employ a supervised learning based We feel entailing the computer in understanding or even pro- method to explore the space of visually pleasing calligraphy. -

City and College Partnerships Between Baden-Württemberg and China

City and College Partnerships between Baden-Württemberg and China City Partnership Collage Partnership Karlsruhe Mannheim Mosbach Stuttgart Zhenjiang (Jiangsu), Qingdao (Shandong) Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University Nanjing (Friendship City) Karlsruher Institute for Technology Mosbach - Suzhou, (Jiangsu): Institute of Technology University Mannheim - Nanjing, (Jiangsu): Southeast University - Peking: Institute of Technology, - Xiamen, (Fujian): Xiamen University Tsinghua University - Shanghai: Tongji University School of Economics & Management, University Stuttgart - Shanghai: Jiao Tong University, Tongji University - Peking: Institute of Technology, East China University of Science and Technology, Central Academy of Fine Arts University of Education Karlsruhe Jiao Tong University, Marbach am Neckar - Shanghai: Jiao Tong University, - Shanghai: East China Normal University Shanghai Advanced Insitute Tongji University Tongling (Provice of Anhui) of Finance, Karlsruhe University for Arts and Design Fudan University State-owned Academy of Visual Art Stuttgart - Peking: Central Academy of Fine Arts - Peking: University of International - Hangzhou, (Zhejiang): China Academy of Art - Wuhan, (Hubei): Huazhong University of Science and Business and Economics, - Shenyang, (Liaoning): Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts Technology, China Academy of Arts Tsinghua University, Heilbronn Peking University Guanghua University of Media Science Stuttgart Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University Stuttgart School of Management University of Heilbronn -

Big Business, Selling Shrimps: the Market As Imaginary in Post-Mao

For decades critics have written disapprovingly about the relationship between the market and art. In the 1970s proponents of institutional critique wrote in Artforum about the degrading effects of money on art, and in the 1980s Robert Hughes (author of Shock of the New and director of The Mona Lisa Curse) compared the 01/07 deleterious effect of the market on art to that of strip-mining on nature.1ÊMore recently, Hal Foster has disparaged the work of some of the markets hottest art stars – Takashi Murakami, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons – declaring that their pop concoctions lack tension, critical distance, and irony, offering little more than “giddy delight, weary despair, or a manic- Jane DeBevoise depressive cocktail of the two.”2 And Walter Robinson has spoken about the ability of the market to act as a kind of necromancer, Big Business, reanimating mid-century styles of abstract painting for the purposes of flipping canvas like Selling real estate – a phenomenon he calls “zombie formalism.”3 Shrimps: The ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊMoralistic attacks against the degrading impact of the market on art are not unique to US- based critics. Soon after the end of the Cultural Market as Revolution, when few people think China had any art market at all, plainly worded attacks on Imaginary in commercialism appeared regularly in the nationally circulated art press. As early as 1979, a n i Jiang Feng, the chair of the Chinese Artists h Post-Mao China C Association, worried in writing that ink painters o a were churning out inferior works in pursuit of M - t 4 s material gain.Ê ÊIn 1983, the conservative critic o P Hai Yuan wrote that “owing to the opportunity for n i y high profit margins, many painters working in oil r a n or other mediums have switched to ink painting.” i g e a s And, what was worse, to maximize their gain, i m o I v these artists “sought to boost their productivity s e a B 5 t e by acting like walking photocopy machines.” In e D k e r the 1990s supporters of experimental oil a n a M painting also came under fire.