TOCC0356DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Download the Fall 2016 Issue (PDF)

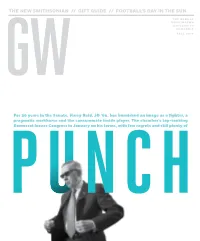

THE NEW SMITHSONIAN // GIFT GUIDE // FOOTBALL’S DAY IN THE SUN THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2016 For 30 years in the Senate, Harry Reid, JD ’64, has burnished an image as a fighter, a pragmatic workhorse and the consummate inside player. The chamber’s top-ranking Democrat leaves Congress in January on his terms, with few regrets and still plenty of gw magazine / Fall 2016 GW MAGAZINE FALL 2016 A MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS CONTENTS [Features] 26 / Rumble & Sway After 30 years in the U.S. Senate—and at least as many tussles as tangos—the chamber’s highest-ranking Democrat, Harry Reid, JD ’64, prepares to make an exit. / Story by Charles Babington / / Photos by Gabriella Demczuk, BA ’13 / 36 / Out of the Margins In filling the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture, alumna Michèle Gates Moresi and other curators worked to convey not just the devastation and legacy of racism, but the everyday experience of black life in America. / By Helen Fields / 44 / Gift Guide From handmade bow ties and DIY gin to cake on-the-go, our curated selection of alumni-made gifts will take some panic out of the season. / Text by Emily Cahn, BA ’11 / / Photos by William Atkins / 52 / One Day in January Fifty years ago this fall, GW’s football program ended for a sixth and final time. But 10 years before it was dropped, Colonials football rose to its zenith, the greatest season in program history and a singular moment on the national stage. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire.␣ Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers.␣ At the same time it aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire.␣ Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions.␣ Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), and Bruder Lustig, which further explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend.␣ Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action. Marschner’s Hans -

The Current Great Gate of Kiev Built in 1982 in Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: ©Mark Laycock

The current Great Gate of Kiev built in 1982 in Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: ©Mark Laycock Nieweg Chart Pictures at an Exhibition; Картинки c выставки; Kartinki s vystavki; Tableaux d'une Exposition By Modeste Mussorgsky A Guide to Editions Up Date 2018 Clinton F. Nieweg 1. Orchestra editions 2. String Orchestra editions 3. Wind Ensemble/Band editions 4. Chamber Ensemble editions 5. Other non-orchestral arrangements 6. Keyboard editions 7. Sites, Links and Documentation about the 'Pictures' 8. Reference Sources 9. Publishers and Agents In this chart the composer’s name is spelled as cataloged by the publishers. They use Модест Мусоргский, Moussorgski, Musorgskii, Musorgskij, Musorgsky, Mussorgskij, or Mussorgsky. He was inspired to compose Pictures at an Exhibition quickly, completing the piano score in three weeks 2–22 June 1874. Movement Codes 1. Promenade I 2. Gnomus 3. Promenade II 4. The Old Castle 5. Promenade III 6. Tuileries: Children Quarreling at Play 7. Bydło 8. Promenade IV 9. Ballet of Unhatched Chicks 10. Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle 11. Promenade V 12. The Market Place at Limoges - Le Marché 13. Catacombæ (Sepulcrum Romanum) 14. Cum Mortuis in Lingua Mortua 15. Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba-Yaga) 16. The Great Gate of Kiev Recordings: For information about recordings of all 606 known arrangements and 1041 recordings (as of August 2015), see the chart by David DeBoor Canfield, President, International Kartinki s vystavki Association. www.daviddeboorcanfield.org Click on Exhibition. Click on Arrangements. For the August 2018 update of 1112 recordings see Canfield in Sites, Links and Documentation about the 'Pictures' below. -

Deine Ohren Werden Augen Machen

Deine Ohren werden Augen machen. 3 4. Programmwoche 15 . August – 21. August 2020 ARD Radiofestival 2020 in der Zeit vom 18. Juli bis 12. September 2019 Ausführliche Hinweise hierzu finden Sie ab Anfang Juli unter www.ardradiofestival.de Samstag, 15. August 2020 09.04 – 09.35 Uhr FEATURE Sommerserie Metropolen Einmal Sankt Petersburg über Leningrad und zurück Von Jens Sparschuh „Nichts Schöneres gibt es als den Newski-Prospekt“, schrieb Gogol über diesen traumhaften Boulevard in Sankt Petersburg. Ein Gebäude ragt extravagant heraus: das Singer-Haus. 1904 als russische Filiale des Nähmaschinenimperiums eröffnet, spiegelt sich in seinen jugendstilechten Fensterscheiben auf ganz besondere Weise die Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Jens Sparschuh ist als Wiedergänger unterwegs in der Stadt, in der 1917 nach einer Eisenbahnfahrt durch Deutschland im angeblich plombierten Zug ein gewisser Uljanow „an den Schlaf der Welt“ rührte. Sparschuh, der in den 1970er Jahren in Leningrad studiert hat, flaniert über den Newski-Prospekt und erzählt entlang dieser Straße von einem ganzen Jahrhundert. Regie: Wolfgang Rindfleisch Produktion: MDR 2017 19.04 – 19.30 Uhr KULTURTERMIN weiter lesen – das LCB im rbb Jonas Eika liest „Nach der Sonne“ Am Mikrofon: Nadine Kreuzahler „Literatur kann dazu beitragen, uns eine eigene Sprache für die Welt und für unsere Erfahrungen zu geben, die uns nicht verlogen und unzureichend vorkommt ... Literatur kann Energie zu politischer Veränderung freisetzen“, sagt Jonas Eika (Jahrgang 1991) in einem Interview. „Nach der Sonne“, aus dem Dänischen von Ursel Allenstein, ist sein erstes Buch auf Deutsch. Der bisher jüngste Preisträger des Literaturpreises des Nordischen Rats legt Erzählungen mit mitunter brutaler Körperlichkeit vor, die in einer von ökonomischen Begierden durchzogenen Gesellschaft spielen und wie selbstverständlich in Welten führen, die mit einem simplen Realitätsbegriff nicht immer zu fassen sind. -

Montag, 17.08.2020 17

Montag, 17.08.2020 17. August 1955 - Das Leitung: Herbert Kegel Gesetz über das ab 02:03: Kassenarztrecht wird Ottorino Respighi: verabschiedet Feste romane; New York 10:50 WDR 2 - Wilfried Philharmonic, Leitung: Schmickler Giuseppe Sinopoli 13:00 WDR 2 Das Robert Fuchs: 00:00 1LIVE Fiehe Mittagsmagazin Streicherserenade e-Moll, Freestylesendung mit Klaus Darin: op. 21; Kölner Kammerorchester, Leitung: Fiehe zur vollen Stunde WDR seit 22:00 Uhr aktuell Christian Ludwig Erich Wolfgang Korngold: 01:00 Die junge Nacht der ARD zur halben Stunde WDR aktuell und Lokalzeit auf Sextett D-Dur, op. 10; Mit Lara Heinz Thomas Selditz, Viola; Darin: WDR 2 Màrius Díaz, Violoncello; zur vollen Stunde WDR 15:00 WDR 2 Der Nachmittag Aron Quartett aktuell Darin: Michail Ippolitow-Iwanow: 05:00 1LIVE mit Donya Farahani zur vollen Stunde WDR aktuell Sinfonie Nr. 1 e-Moll, op. 46; und dem Bursche zur halben Stunde bis 17:30 Bamberger Symphoniker, Die tägliche, aktuelle Leitung: Gary Brain Morgen-Show in 1LIVE WDR aktuell und Lokalzeit auf WDR 2 ab 04:03: 10:00 1LIVE Tina Middendorf 18:40 WDR 2 Stichtag Antonín Dvořák: Der Vormittag in 1LIVE (Wiederholung von 09:40) Die Waldtaube, op. 110; 14:00 1LIVE Kammel und Kühler 19:00 WDR 2 Jörg Thadeusz Münchner Der Nachmittag in 1LIVE Darin: Rundfunkorchester, Leitung: 18:00 1LIVE mit Lisa Kestel zur vollen Stunde WDR Peter Gülke Die Themen des Tages im aktuell Johann Sebastian Bach: Sektor Suite G-Dur, BWV 1007; 20:00 WDR 2 POP! Pieter Wispelwey, 20:00 1LIVE Plan B Darin: Der Abend in 1LIVE - im zur vollen Stunde WDR Violoncello Nikolaj Rimskij-Korsakow: Zeichen der Popkultur aktuell Mit Tilmann Köllner Konzert-Fantasie h-Moll, op. -

Lodge News July 2019

Lodge Waikato 475 OF FREE AND ACCEPTED FREEMASONS JULY 2019 P L U M B L I N E Students from Ngaruawahia High-school Havana Klink and Adam Kimpton with Mrs Kimpton. Recipients of financial assistance to enable them to attend ‘ O utward Bound ’ “ O utdoor Challenge and Adventure Teen Course. ” NOTICE PAPER MASTER W.Bro. Graham Hallam 40 Wymer Terrace, Hamilton PH. 07 855 5198 027 855 5198 SENIOR WARDEN JUNIOR WARDEN W.Bro Adrian de Bruin W.Bro Andre Schenk 265A Hakirimata Rd 11 Beaufort Place Ngaruawahia Flagstaff, Hamilton. Ph. 07 824 7234 ( eve ) Ph 027 5784 060 TREASURER SECRETARY W.Bro. Alan Harrop W.Bro. Bill Newell 18 Cherrywood St Villa 19 - St. Kilda Retirement Village Pukete, Hamilton 91 Alan Livingstone Drive, Cambridge, Ph 027 499 5733 021 061 8828 Dear Brother, You are hereby summoned to attend the Regular Monthly Meeting of Lodge Waikato, to be held in the Hamilton East Masonic Centre, Grey St., Hamilton East , on Thursday 18th July 2019 at 6.30pm Ceremony: - Lodge - .Installation - W.Bro Adrian de Bruin 1. Confirmation of Minutes 2. Accounts payable 3. Treasurer ’ s report 4. Correspondence 5. Almoner ’ s report 6. General Business 7. Notice of Motion W.Bro Bill Newell - Hon Sec Officers of the Lodge I.P.M. - W.Bro Willy Willetts Dep. Master - W.Bro Bob Ancell Sen. Deacon - Bro Trevor Langley Jun. Deacon - W.Bro Dennis Mead Chaplain - W.Bro John Dickson Almoner - W.Bro Graham Hallam Secretary - W.Bro Bill Newell Ass Secretary - W.Bro John Evered Dir. of Ceremony - W.Bro Don McNaughton Ass. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 29, Numbers 1 & 2 2009 719 Twinridge Lane Table of Contents Richmond, VA 23235-5270 T: (804) 553-1378; F: (804) 553-1876 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Maestro Dean Dixon page 1 Website: www.conductorsguild.org . Advancing the Art and Profession (1915-1976): A Forgotten Officers American Conductor by Rufus Jones, Jr. D.M.A. Michael Griffith, President John Farrer, Secretary James Allen Anderson, President-Elect Lawrence J. Fried, Treasurer Gordon J. Johnson, Vice-President Sandra Dackow, Past President Visionary Leadership and the page 6 Board of Directors Conductor Ira Abrams Claire Fox Hillard Lyn Schenbeck by Nancy K. Klein, Ph.D. Leonard Atherton Paula K. Holcomb Michael Shapiro Christopher Blair Rufus Jones, Jr.* Jonathan Sternberg* David Bowden John Koshak Kate Tamarkin Creating a Fresh Approach to page 12 John Boyd Anthony LaGruth Harold Weller Conducting Gesture Jeffrey Carter Peter Ettrup Larsen Kenneth Woods by Charles L. Gambetta, D.M.A. Stephen Czarkowski Brenda Lynne Leach Amanda Winger* Charles Dickerson III David Leibowitz* Burton A. Zipser* Kimo Furumoto Lucy Manning *ex officio Mussorgsky/Ravel’s Pictures at an page 31 Jonathan D. Green Michael Mishra Exhibition : Faithful to the Wrong Earl Groner John Gordon Ross Source by Jason Brame Advisory Council Pierre Boulez Tonu Kalam Maurice Peress Emily Freeman Brown Wes Kenney Donald Portnoy Score and Parts: Maurice page 43 Michael Charry Daniel Lewis Barbara Schubert Ravel’s Bolero Harold Farberman Larry Newland Gunther Schuller by Clinton F. Nieweg and Nancy M. Adrian Gnam Harlan D. Parker Leonard Slatkin Bradburd Samuel Jones Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Leonard Slatkin Maurice Abravanel Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Marin Alsop James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leon Barzin Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Leonard Bernstein Max Rudolf David Zinman Pierre Boulez Robert Shaw Thelma A. -

Programska Knjižica

24. SARAJEVSKE VEČERI MUZIKE 2018 Srijeda, 09.05.2018. – Petak, 18.05.2018. PROGRAMSKA KNJIŽICA Poštovani ljubitelji muzike, SVEM nastavlja tradiciju i u svom 24. izdanju donosi pregršt vrijednih muzičkih događaja koji će u deset festivalskih dana našu prijestolnicu ponovo približiti evropskim kulturnim centrima. Muzika kojoj je Festival u potpunosti posvećen tu je da oplemenjuje, da ne ostavi ravnodušnim, da potakne na razmišljanje, ali i na djelovanje. S željom da svi festivalski sadržaji ostave trag, SVEM s ponosom predstavlja 7 koncerata i muzičku radionicu koji će našu publiku povesti na uzbudljivo muzičko putovanje od španske i argentinske muzike, preko kamernih ostvarenja zapadnoevropske tradicije, do muzike Petra Iljiča Čajkovskog kojom se Festival pridružuje globalnom obilježavanju 125. godišnjice smrti ovog velikog ruskog kompozitora. Vrhunski umjetnici su i ove godine pristali podijeliti djeliće svoje umjetnosti i na sarajevskoj pozornici. Mladi pijanista Aljoša Jurinić počastit će nas izvedbom Koncerta za klavir i orkestar br. 2 Sergeja Prokoeva; svestrani Antonio Serrano na usnoj harmonici zvukom će nas odvesti u jedan drugačiji svijet; Beogradski kamerni hor uz dirigenta Vladimira Markovića otkrivat će zvučne dimenzije duhovnosti; hornista Boštjan Lipovšek udružit će snage s prijateljima i kolegama i podijeliti zadovoljstvo kamernog muziciranja; gitarista Petrit Çeku provest će nas kroz različite epohe muzičkog stvaralaštva, dok će violinista Sergej Krylov veličansvenim Koncertom za violinu i orkestar u D duru Petra Iljiča Čajkovskog dati svoj doprinos obilježavanju jednog značajnog jubileja. Ne zaboravimo i one iznimno talentovane mlade umjetnike, Saru Čano i Nikolu Pajanovića, koji će na koncertu “U susret SVEM-u” nastupiti kao potomci nekadašnjih generacija studenata Muzičke akademije u Sarajevu. -

A Vision for a Comprehensive Petroleum Arbitration Regime in Iraq

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Modernising Iraq : a vision for a comprehensive petroleum arbitration regime in Iraq Al-Bidery, Sinan Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Modernising Iraq: A Vision for a Comprehensive Petroleum Arbitration Regime in Iraq By Sinan Abdulhamza Al-Bidery A thesis submitted to the University of Bangor, School of Law in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2014 Acknowledgement: I would like to express my deepest thanks to a number of persons and institutions who have helped and supported me to complete my Ph.D studies. My first and foremost thanks are going to the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for granting me a scholarship to complete my study and also I would like to thank the Iraqi Culture Attaché. -

Piano Concerto No. 12 in a Major by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Was Composed Along

www.festivalmaribor.si DOBRODOŠLI V EVROPSkI PRESTOLNICI kULTURE EUROPEAN CAPITAL OF CULTURE WELCOMES YOU www.maribor2012.eu Festival Maribor v kooprodukciji z Javnim zavodom Maribor 2012 / The Maribor Festival in coproduction with Public Institution Maribor 2012 Koncerte je podprlo Ministrstvo za kulturo Republike Slovenije / Concerts are supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia Koproducenti Producent / Co - Producers: / Producer: UVODNIKI / EDITORIALS SANJARIL SEM O TEM, DA BI NA LETošnJEM FESTIVALU »Toda zelo dolgo ni bilo atomov ali vesolja, v katerem bi lahko lebdeli. Ničesar ni bilo – nikjer MARIBOR PREDSTAVIL OPERO, pa ne katerokoli temveč Čarobno popolnoma ničesar. Razen nekaj nepredstavljivo majhnega, kar znanstveniki imenujejo piščal. Potrebovali bi gore denarja za razkošno scenografijo, enkratnost. In kot kaže je bilo to dovolj.« orkester in ruske soliste. Zamišljal sem si silhuete opernih zvezd, »… en proton se je stisnil na milijardinko svoje običajne velikosti.« kako stopajo iz limuzin in nakičene obiskovalce v krznenih plaščih, ki se sprehajajo po sveže pozlačenih ulicah Maribora … »… vsak delček snovi od tod do roba stvarstva (KARKOLI pač že to pomeni).« Prekleta finančna kriza, zdaj pa bo iz tega le en velik nič. »… in jih stisne v prostor, ki je tako neznatno ozek, da je popolnoma brez dimenzij.« DOBRODOŠLI Dobesedno NIČ. Tako opisuje dogodke, ki so pripeljali do velikega poka. Ko smo spoznali, da so operne zvezde predrage in da nam Vendar to ni »Nič«. Prav gotovo je opisal nekaj. NA FESTIVALU njihova prepoznavnost ni dosegljiva, se je moja operna fantazija FINCI imajo najboljšo besedo za Nič. Enostavno ne obstaja. Beseda ne obstaja!! To! No, zdaj razblinila; imel sem tri dni časa, da se spomnim česa drugega.