Conducting Gestures. Institutional and Educational Construction Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra

HansSchmidt-lsserstedt and the StockholmPhilharmonic Orchestra (1957) TheStockholm Philharmonic Orchestra - ALL RECORDINGSMARKED WITH ARE STEREO BIS-CD-421A AAD Totalplayingtime: 71'05 van BEETHOVEN,Ludwig (1770-1827) 23'33 tr SymphonyNo.9 in D minor,Op.125 ("Choral'/, Fourth Movemenl Gutenbuts) 2'.43 l Bars1-91. Conductor.Paavo Berglund Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall 25thMarch 19BB Fadiorecording on tape:Radio Stockholm 1',44 2. Bars92' 163. Conductor:Antal Dor6t Liveconcerl at the StockholmConcert Hall 15thSeptember 1976 Privaterecording on tape.SFO B 276lll 1',56 3 Bars164 '236. Soloist:Sigurd Bjorling, bass Conduclor.Antal Dordti '16th Liveconcert at theStockholm Concert Hall December 1967 Privaterecording on tape.SFO 362 Recordingengineer. Borje Cronstrand 2',27 4 Bars237 '33O' Soloists.Aase Nordmo'Lovberg, soprano, Harriet Selin' mezzo-soprano BagnarUlfung, tenor, Sigurd Biorling' bass Muiit<alisxaSallskapet (chorus master: Johannes Norrby) Conductor.Hans Schmidt-lsserstedt Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall, 19th May 1960 Privaterecording on tape SFO87 Recordingengineer' Borje Cronstrand Bars331 -431 1IAA Soloist:Gosta Bdckelin. tenor MusikaliskaSdllskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norrbv) Conductor:Paul Kletzki Liveconcert at the StockholmConcerl Hall, ist Octoberi95B Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 58/849 -597 Bars431 2'24 MusikaliskaSallskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norroy,l Conductor:Ferenc Fricsay Llverecording at the StockholmConcert Hall,271h February 1957 Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 571199 Bars595-646 3',05 -

View Album Insert

music director patron sponsors Lan Shui a standing ovation for our corporate partners official official official official official airline hotel radio station postage sponsor outdoor media partners Schumann Symphony Spectacular Symphonic Fantasy LEE FOUNDATION Supported by various corporate sponsors and individual donors, the Singapore Symphony Orchestra is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee and registered under the Charities Order. Singapore Symphony Orchestra 11 Empress Place, Victoria Concert Hall, Singapore 179558 Sat, 30 Jan 10 Company registration no: 197801125M Phone +65 6338 1230 (main) Fax +65 6336 6382 Esplanade Concert Hall E-mail [email protected] Website www.sso.org.sg Performing Home of the SSO All Rights Reserved, National Library Board, Singapore For song title, key in 924 and SMS to 72346. Each SMS costs 30 cents. Service provided by MediaCorp Pte Ltd, 6877 7132. All Rights Reserved, National Library Board, Singapore Sat, 30 Jan 10 Schumann Symphony Spectacular Symphonic Fantasy Singapore Symphony Orchestra Okko Kamu conductor Dang Thai Son piano Robert Schumann Manfred: Overture, Op. 115 12’00 Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 39’00 Intermission 20’00 Dang Thai Son will sign autographs at the stall foyer Robert Schumann Symphony No. 4 in D minor, Op. 120 28’00 Concert Duration: 1 hr 50 min All Timings Indicated Are Approximate. All Rights Reserved, National Library Board, Singapore “Today it unquestionably ranks among the world’s best… A world-class orchestra that can switch between such radically divergent styles with virtuosic ease.” American Record Guide March/April 2007 All Rights Reserved, National Library Board, Singapore 03 Singapore Symphony Orchestra A premier Asian orchestra gaining recognition around the world, the Singapore Symphony Orchestra (SSO) aims to enrich the local cultural scene, serving as a bridge between the musical traditions of Asia and the West, and providing artistic inspiration, entertainment and education. -

KONSERTTIELÄMÄ HELSINGISSÄ SOTAVUOSINA 1939–1944 Musiikkielämän Tarjonta, Haasteet Ja Merkitys Poikkeusoloissa

KONSERTTIELÄMÄ HELSINGISSÄ SOTAVUOSINA 1939–1944 Musiikkielämän tarjonta, haasteet ja merkitys poikkeusoloissa Susanna Lehtinen Pro gradu -tutkielma Musiikkitiede Filosofian, historian ja taiteiden tutkimuksen osasto Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto Lokakuu 2020 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Humanistinen tiedekunta / Filosofian, historian ja taiteiden tutkimuksen osasto Tekijä – Författare – Author Susanna Lehtinen Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Konserttielämä Helsingissä sotavuosina 1939–1944. Musiikkielämän tarjonta, haasteet ja merkitys poikkeusoloissa. Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Musiikkitiede Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma Lokakuu 2020 117 + Liitteet Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tässä tutkimuksessa kartoitetaan elävä taidemusiikin konserttitoiminta Helsingissä sotavuosina 1939–1944 eli talvisodan, välirauhan ja jatkosodan ajalta. Tällaista kattavaa musiikkikentän kartoitusta tuolta ajalta ei ole aiemmin tehty. Olennainen tutkimuskysymys on sota-ajan aiheuttamien haasteiden kartoitus. Tutkimalla sotavuosien musiikkielämän ohjelmistopolitiikkaa ja vastaanottoa haetaan vastauksia siihen, miten sota-aika on heijastunut konserteissa ja niiden ohjelmistoissa ja miten merkitykselliseksi yleisö on elävän musiikkielämän kokenut. Tutkimuksen viitekehys on historiallinen. Aineisto on kerätty arkistotutkimuksen menetelmin ja useita eri lähteitä vertailemalla on pyritty mahdollisimman kattavaan kokonaisuuteen. Tutkittava -

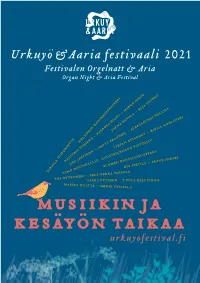

Program 24.6.2021

Urkuyö &Aaria festivaali 2021 Festivalen Orgelnatt & Aria Organ Night & Aria Festival puukko lja Marko Hilpoe – a panula – ozlovski M k leksanteri Wallius jor a irill arbora Hilpo k b – Hov – Helsingin barokkiorkesteriselonen –a stak torikka arttu stefan infonietta s järvinen – sakari Waltterii pétur jiM Men kansallisooppera suo esa pietilä – apiola o Mustakallio -laulukilpailun voittajat t tiM varpula veli- pekka rytkönen – piia saMi luttinen – t uula HällströM Marika Hölttä – Henri uusitalo Musiikin ja kesäyön taikaa urkuyofestival.fi KIRKKO ESPOOSSA KYRKAN I ESBO 3.6.–28.8.2021 Urkuyö &Aaria festivaali Musiikin ja kesäyön taikaa kesäkuu 15.7. Urkuvirtuoosit irti! 3.6. Avajaiskonsertti: Suvi-illan klassikot Jimi Järvinen, Waltteri Torikka, baritoni Arttu Selonen, Barbora Hilpo, alttoviulu Aleksanteri Wallius, urut Marko Hilpo, piano 22.7. Valkeiden öiden romantiikkaa 10.6. Matvejeff & Katajala & Stefan Astakhov, baritoni Tapiola Sinfonietta Kiril Kozlovski, piano Ville Matvejeff, kapellimestari 29.7. Timo Mustakallio -kilpailun voittajat 2021 Tuomas Katajala, tenori Tuula Hällström, piano Tapiola Sinfonietta 17.6. Kesäyön sävelsäihkettä elokuu Marika Hölttä, koloratuurisopraano 5.8. Suomen kansallisooppera: Salainen kutsu Henri Uusitalo, basso Tarmo Peltokoski, kapellimestari Erkki Korhonen, piano Sonja Herranen, sopraano 24.6. Juhannusiltamat Suomen kansallisoopperan orkesteri Piia Rytkönen, sopraano 12.8. Liedin vuodenajat Veli-Pekka Varpula, tenori Sami Luttinen, basso Erkki Korhonen, piano ja urut Tuula Hällström, piano 19.8. Improvisaation -

Scaramouche and the Commedia Dell'arte

Scaramouche Sibelius’s horror story Eija Kurki © Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., CopenhaGen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killinG him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. HiGhtower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955). This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine. After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have 1 attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared. Previous research There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. -

Anna-Maria Helsing.18.19.Dt

BIOGRAPHIE ANNA -MARIA HELSING | DIRIGENTIN Anna-Maria Helsing hat sich einen hervorragenden Ruf bei führenden skandinavischen Orchestern und Opernhäusern erarbeitet. 2010 wurde Anna-Maria Helsing als erste Frau an der Spitze eines finnischen Orchesters zur Chefdirigentin des Oulu Symphony Orchestra für drei Jahre ernannt. Innerhalb kurzer Zeit hat die finnische Dirigentin alle großen finnischen und schwedischen Orchester wie das Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, Tampere Philharmonic, Tapiola Sinfonietta, Orchester der Finnischen Nationaloper, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Göteborger Symphoniker, Swedish Radio Symphony, Malmö Symphony , Norrköping Symphony Orchestra, Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Trondheim Symphony, Iceland Symphony und Odense Symphony dirigiert. Außerdem stand sie am Pult der Royal Danish Opera, Royal Swedish Opera Orchestra, Gothenburg Opera Orchestra, Malmö Opera Orchestra, Norrlands Operan Orchestra, Västeras Sinfonietta, Nordic Chamber Orchestra, Estonian National Orchestra sowie die Orchester in Braunschweig, Jena und Hagen. Vor kurzem gab sie ihr gefeiertes Debüt beim BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. An der Finnischen Nationaloper debütierte Helsing 2008 mit Adriana Mater von Kaija Saariaho. Sie leitete eine Reihe von Uraufführungen, wie Momo an der Royal Danish Opera, Magnus-Maria von Karólína Eiríksdóttir auf Tournee in Skandinavien sowie Hallin Janne von Jukka Linkola mit der Jyväskylä Sinfonia. Helsing dirigierte auch Opern von Mozart, Cimarosa, Puccini, Mascagni, Madetoja und Bernstein an der Tampere Opera und beim Savonlinna Opernfestival um nur einige zu nennen. Anna-Maria Helsing hat eine besondere Affinität für den Klang und Stil der Moderne und zeitgenössische Musik. Erneute Einladungen folgen beim Finnish Radio Symphony, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Göteborger Symphoniker, Iceland Symphony, Trondheim Symphony, Avanti! Chamber Orchestra, North Iceland Symphony/Faroer Symphony, u.a. -

SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER the STARS BENJAMIN NORTHEY DIANA DOHERTY CONDUCTOR OBOE Principal Oboe, John C Conde AO Chair

SYDNEY SYMPHONY Photo: Photo: Jamie Williams UNDER THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA I AUSTRALIA PROGRAM Dmitri Shostakovich (Russian, 1906–1975) SYDNEY Festive Overture SYMPHONY John Williams (American, born 1932) Hedwig’s Theme from Harry Potter UNDER THE Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian, 1756–1791) Finale from the Horn Concerto No.4, K.495 STARS Ben Jacks, horn SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA I AUSTRALIA THE CRESCENT Hua Yanjun (Chinese, 1893–1950) PARRAMATTA PARK Reflection of the Moon on the Lake at Erquan 8PM, 19 JANUARY 120 MINS John Williams Highlights from Star Wars: Imperial March Benjamin Northey conductor Cantina Music Diana Doherty oboe Main Title Ben Jacks horn INTERVAL Sydney Symphony Orchestra Gioachino Rossini (Italian, 1792–1868) Galop (aka the Lone Ranger Theme) from the overture to the opera William Tell Percy Grainger (Australian, 1882–1961) The Nightingale and the Two Sisters from the Danish Folk-Song Suite Edvard Grieg (Norwegian, 1843–1907) Highlights from music for Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt: Morning Mood Anitra’s Dance In the Hall of the Mountain King Ennio Morricone (Italian, born 1928) Theme from The Mission Diana Doherty, oboe Josef Strauss (Austrian, 1827–1870) Music of the Spheres – Waltz Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian, 1840–1893) 1812 – Festival Overture SYDNEYSYDNEY SYMPHONY SYMPHONY UNDER UNDER THE STARS THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER THE STARS BENJAMIN NORTHEY DIANA DOHERTY CONDUCTOR OBOE Principal Oboe, John C Conde AO Chair Benjamin Northey is Chief Conductor of the Christchurch Diana Doherty joined the Sydney Symphony Orchestra as Symphony Orchestra and Associate Conductor of the Principal Oboe in 1997, having held the same position with Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. -

Itunes Store and Spotify Recordings

A+ Music Memory 2016-2017 iTunes Store and Spotify Recordings Bach Pachelbel Canon and Other Baroque Favorites, track 12, Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV1067: Badinerie (James Galway, Zagreb Soloists & I Solisti di Zagreb, Universal International BMG Music, 1978). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/pachelbel-canon-other- baroque/id458810023 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/4bFAmfXpXtmJRs2t5tDDui Bartók Bartók: Hungarian Pictures – Weiner: Hungarian Folk Dance – Enescu: Romanian Rhapsodies, track 2, Magyar Kepek (Hungarian Sketches), BB 103: No. 2. Bear Dance (Neeme Järvi & Philharmonia Orchestra, Chandos, 1991). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/bartok-hungarian-pictures/id265414807 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/5E4P3wJnd2w8Cv1b37sAgb Beethoven Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 8, 14, 23 & 26, track 6, Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13 – “Pathétique,” III. Rondo (Allegro), (Alfred Brendel, Universal International Music B.V., 2001) iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/beethoven-piano-sonatas- nos./id161022856 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/2Z0QlVLMXKNbabcnQXeJCF Brahms Best of Brahms, track 11, Waltz No. 15 in A-Flat Minor, Op. 59 [Note: This track is mis-named: the piece is in A-Flat Major, from Op. 39] (Dieter Goldmann, SLG, LLC, 2009). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/best-of-brahms/id320938751 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/1tZJGYhVLeFODlum7cCtsa A+ Mu Me ory – Re or n s of Clarke Trumpet Tunes, track 2, Suite in D Major: IV. The Prince of Denmark’s March, “Trumpet Voluntary” (Stéphane Beaulac and Vincent Boucher (ATMA Classique, 2006). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/trumpet-tunes/id343027234 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/7wFCg74nihVlMcqvVZQ5es Delibes Flower Duet from Lakmé, track 1, Lakmé, Act 1: Viens, Mallika, … Dôme épais (Flower Duet) (Dame Joan Sutherland, Jane Barbié, Richard Bonynge, Orchestre national de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Decca Label Group, 2009). -

Kaapo Johannes Ijas B

CV Kaapo Johannes Ijas b. 26.07.1988 Solvikinkatu 13 C 38 00990 Helsinki +358 44 5260788 [email protected] www.kaapoijas.com Kaapo Ijas (b.1988) is the Mills Williams Junior Fellow in Conducting at the Royal Northern College of Music. He has been fiercely interested in composing, performance, drama, group dynamics and the orchestra itself for all his life. In 2012 it lead him to conducting studies first in Sibelius Academy then Zürcher Hochschule der Künste and ultimately Royal College of Music in Stockholm where he graduated from in spring of 2017. His teachers during his studies and masterclasses include Jorma Panula, Johannes Schlaefli, Jaap van Zweden, Riccardo Muti, Esa-Pekka Salonen, David Zinman, Neeme and Paavo Järvi and Atso Almila. Ijas has conducted i.a. Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Norrköping SO, South Jutland SO, Musikkollegium Winterthur, Gävle Symfoniorkester, Kurpfälzisches Kammerorchester (Mannheim), Hradec Kralove Philharmonia, KMH Symphony Orchestra, Seinäjoki City Orchestra, KammarensembleN, Norrbotten NEO, Swedish Army Band, Helsinki Police band and numerous other project ensembles and choirs during masterclasses and in concerts. Ijas has been invited to various prestigious masterclasses including Gstaad Menuhin Festival 2018 with Jaap van Zweden, Riccardo Muti Opera Academy 2017 in Ravenna, the 8th Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich masterclass with David Zinman in 2017 and Järvi Academy with Paavo and Neeme Järvi in 2016. He was semifinalist in Donatella Flick Conducting Competition 2016 after invited to the competition with 2 weeks notice and among the top 7 in Cadaqués Conducting Competition 2017. In 2018 Ijas was selected as 24 conductors from 566 applicants to take part in Nikolai Malko competition in Copenhagen and won the 3rd prize in Jorma Panula Conducting Competition in Vaasa. -

Sakari Oramo, Conductor Pekka Kuusisto, Violin Ottorino

Sakari Oramo, conductor Pekka Kuusisto, violin Ottorino Respighi: Fontane di Roma (The Fountains of Rome) 18 min I La fontana di Valle Giulia all’alba (The Fountain of the Valle Giulia at Dawn) (Andante mosso) II La fontana del Tritone al mattino (The Triton Fountain in Early Morning) (Vivo) III La fontana di Trevi al meriggio (The Trevi Fountain at Midday) (Allegro moderato - Allegro vivace - Largamente) IV La fontana di Villa Medici al tramonto (The Fountain of the Villa Medici at Sunset) (Andante) Samuel Barber: Violin Concerto, Op. 14 22 min I Allegro II Andante III Presto in moto perpetuo INTERVAL 20 min Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 103 in E flat major, “Drum roll” 29 min I Adagio - Allegro con spirito - Adagio - Tempo 1 II Andante più tosto allegretto III Menuetto (Minuet) - Trio IV Finale (Allegro con spirito) Interval at about 7.45 pm. Th e concert ends at about 8.45 pm. Broadcast live on YLE Radio 1 and the Internet (www.yle.fi /rso). 1 Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936): Fontane di Roma (The Fountains of Rome, 1916) Respighi studied the viola and composition in sations and visions suggested to him by four of St. Petersburg, in the class of Rimsky-Korsakov Rome’s fountains contemplated at the hour in and others. His music was later infl uenced by which their character is most in harmony with French Impressionism, from which he selected the surrounding landscape, or in which their colours for his masterly handling of the orches- beauty appears most suggestive to the observ- tra. He is best remembered for his Roman Tril- er.” Th e day dawns at the fountain of the Valle ogy for orchestra. -

Los Angeles Philharmonic

LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Critical Acclaim “The most successful American orchestra.” - Los Angeles Times “It should be chiseled above the doors of every symphony hall: What an orchestra plays matters as much as how it plays, if not more so. By that measure a strong case can be made that the Los Angeles Philharmonic…is the most important orchestra in the country.” - The New York Times “If ever an orchestra was riding the crest of a wave, it is the Los Angeles Philharmonic.” - The Times (London) “…the most multi-faceted orchestra in the world and certainly the one putting the greatest emphasis on music of our time.” - Los Angeles Times “Under Salonen, the [Los Angeles] Philharmonic became the most interesting orchestra in America; under Dudamel, it shows no signs of relinquishing the title.” - The New Yorker Best Orchestras of 2012 – #1) Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra – “The most talked-about and widely-travelled US orch, carrying Brand Dudamel to all four corners of the earth, split a Mahler cycle between US and Venezuela, advanced tremendous outreach work across its own urban area.” - Norman Lebrecht’s Slipped Disc “The L.A. Phil still boasts the most varied and venturesome offerings of any major orchestra.” - Los Angeles Times “At a time when many orchestras are offering ‘safer,’ crowd-pleasing repertoire picks online, it’s refreshing to see the LA Phil coming out of the gate with programming that speaks to why it is at the forefront of American orchestras today.” - Billboard “‘Blow bright’ is the seventh work commissioned and performed by the L.A. -

Takemi Sosa Magnus Lindberg — Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy

Magnus Lindberg —Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy ACTA SEMIOTICA FENNICA Editor Eero Tarasti Associate Editors Paul Forsell Richard Littlefield Editorial Board Pertti Ahonen Jacques Fontanille André Helbo Pirjo Kukkonen Altti Kuusamo Ilkka Niiniluoto Pekka Pesonen Hannu Riikonen Vilmos Voigt Editorial Board (AMS) Márta Grabócz Robert S. Hatten Jean-Marie Jacono Dario Martinelli Costin Miereanu Gino Stefani Ivanka Stoianova TAKEMI SOSA Magnus Lindberg — Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy in Aura and the Symphonic Triptych Acta Semiotica Fennica LIII Approaches to Musical Semiotics 26 Academy of Cultural Heritages, Helsinki Semiotic Society of Finland, Helsinki 2018 E-mail orders [email protected] www.culturalacademy.fi https://suomensemiotiikanseura.wordpress.com Layout: Paul Forsell Cover: Harumari Sosa © 2018 Takemi Sosa All rights reserved Printed in Estonia by Dipri OÜ ISBN 978-951-51-4187-3 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-51-4188-0 (PDF) ISSN 1235-497X Acta Semiotica Fennica LIII ISSN 1458-4921 Approaches to Musical Semiotics 26 Department of Philosophy and Art Studies Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki Finland Takemi Sosa Magnus Lindberg — Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy in Aura and the Symphonic Triptych Doctoral Dissertation Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki (the main building), in auditorium XII on 04 May 2018 at 12 o’clock noon. For my Sachiko, Asune and Harunari 7 Abstract The Finnish composer Magnus Lindberg (b. 1958) is one of the leading figures in the field of contemporary classical music. Curiously, despite the fascinating characteristics of Lindberg’s works and the several interesting subjects his mu- sic brings up, his works have not been widely researched.