Tocc0252notes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M. Jones, S.-J. Bradley, T. Lowe, A. Thwaite) Notes to performers by Matthew Jones Walton, Menuhin and ‘shifting’ performance practice The use of vibrato and audible shifts in Walton’s works, particularly the Violin Sonata, became (somewhat unexpectedly) a fascinating area of enquiry and experimentation in the process of preparing for the recording. It is useful at this stage to give some historical context to vibrato. As late as in Joseph Joachim’s treatise of 1905, the renowned violinist was clear that vibrato should be used sparingly,1 through it seems that it was in the same decade that the beginnings of ‘continuous vibrato use’ were appearing. In the 1910s Eugene Ysaÿe and Fritz Kreisler are widely credited with establishing it. Robin Stowell has suggested that this ‘new’ vibrato began to evolve partly because of the introduction of chin rests to violin set-up in the early nineteenth century.2 I suspect the evolution of the shoulder rest also played a significant role, much later, since the freedom in the left shoulder joint that is more accessible (depending on the player’s neck shape) when using a combination of chin and shoulder rest facilitates a fluid vibrato. Others point to the adoption of metal strings over gut strings as an influence. Others still suggest that violinists were beginning to copy vocal vibrato, though David Milsom has observed that the both sets of musicians developed the ‘new vibrato’ roughly simultaneously.3 Mark Katz persuasively posits the idea that much of this evolution was due to the beginning of the recording process. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

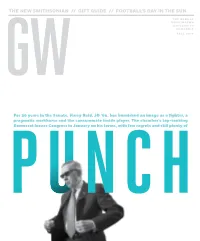

Download the Fall 2016 Issue (PDF)

THE NEW SMITHSONIAN // GIFT GUIDE // FOOTBALL’S DAY IN THE SUN THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2016 For 30 years in the Senate, Harry Reid, JD ’64, has burnished an image as a fighter, a pragmatic workhorse and the consummate inside player. The chamber’s top-ranking Democrat leaves Congress in January on his terms, with few regrets and still plenty of gw magazine / Fall 2016 GW MAGAZINE FALL 2016 A MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS CONTENTS [Features] 26 / Rumble & Sway After 30 years in the U.S. Senate—and at least as many tussles as tangos—the chamber’s highest-ranking Democrat, Harry Reid, JD ’64, prepares to make an exit. / Story by Charles Babington / / Photos by Gabriella Demczuk, BA ’13 / 36 / Out of the Margins In filling the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture, alumna Michèle Gates Moresi and other curators worked to convey not just the devastation and legacy of racism, but the everyday experience of black life in America. / By Helen Fields / 44 / Gift Guide From handmade bow ties and DIY gin to cake on-the-go, our curated selection of alumni-made gifts will take some panic out of the season. / Text by Emily Cahn, BA ’11 / / Photos by William Atkins / 52 / One Day in January Fifty years ago this fall, GW’s football program ended for a sixth and final time. But 10 years before it was dropped, Colonials football rose to its zenith, the greatest season in program history and a singular moment on the national stage. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire.␣ Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers.␣ At the same time it aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire.␣ Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions.␣ Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), and Bruder Lustig, which further explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend.␣ Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action. Marschner’s Hans -

BMS News August 2018

BRITISH MUSIC SOCIETY nAUGUST 2018 ews THE PIPER OF DREAMS A Ruth Gipps perspective ELGAR ENIGMA Rachel Barton Pine’s magnifica musica Agenda British Music Society’s news and events What you missed at the AGM his report of our Annual General Meeting covers the key areas of the Recordings Chairman’s TBritish Music Society’s activities as The generous bequest from Michael follows: Hurd for recordings has finally come to an end unfortunately and it is only to be welcome E-News expected that new releases by the Society will In the summer of 2017, Harold Diamond be less frequent now in number. New 'll keep my address short as the indicated his need to retire from his position opportunities to record will largely depend Chairman's Report from this as the monthly E-news editor. There were on receipt of grants from other funding year's AGM on June 30 is being difficulties finding another member with the bodies. I necessary time and the increasingly In November 2017, the songs of Arthur reproduced in this edition of Printed demanding technological skills to do this job. Benjamin and Edgar Bainton with Susan News. What it will not tell you is In light of this, the decision was made to Bickley (mezzo), Christopher Gillett (tenor) Dominic Daula, our new Journal employ Michael Wilkinson and Nicholas and Wendy Hiscocks (piano) with some Editor, joined the Committee at the Keyworth of Revolution Arts to conduct the funding from The Edgar Bainton Society AGM and John Gibbons revealed work for an agreed sum of £100 per month. -

Deine Ohren Werden Augen Machen

Deine Ohren werden Augen machen. 3 4. Programmwoche 15 . August – 21. August 2020 ARD Radiofestival 2020 in der Zeit vom 18. Juli bis 12. September 2019 Ausführliche Hinweise hierzu finden Sie ab Anfang Juli unter www.ardradiofestival.de Samstag, 15. August 2020 09.04 – 09.35 Uhr FEATURE Sommerserie Metropolen Einmal Sankt Petersburg über Leningrad und zurück Von Jens Sparschuh „Nichts Schöneres gibt es als den Newski-Prospekt“, schrieb Gogol über diesen traumhaften Boulevard in Sankt Petersburg. Ein Gebäude ragt extravagant heraus: das Singer-Haus. 1904 als russische Filiale des Nähmaschinenimperiums eröffnet, spiegelt sich in seinen jugendstilechten Fensterscheiben auf ganz besondere Weise die Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Jens Sparschuh ist als Wiedergänger unterwegs in der Stadt, in der 1917 nach einer Eisenbahnfahrt durch Deutschland im angeblich plombierten Zug ein gewisser Uljanow „an den Schlaf der Welt“ rührte. Sparschuh, der in den 1970er Jahren in Leningrad studiert hat, flaniert über den Newski-Prospekt und erzählt entlang dieser Straße von einem ganzen Jahrhundert. Regie: Wolfgang Rindfleisch Produktion: MDR 2017 19.04 – 19.30 Uhr KULTURTERMIN weiter lesen – das LCB im rbb Jonas Eika liest „Nach der Sonne“ Am Mikrofon: Nadine Kreuzahler „Literatur kann dazu beitragen, uns eine eigene Sprache für die Welt und für unsere Erfahrungen zu geben, die uns nicht verlogen und unzureichend vorkommt ... Literatur kann Energie zu politischer Veränderung freisetzen“, sagt Jonas Eika (Jahrgang 1991) in einem Interview. „Nach der Sonne“, aus dem Dänischen von Ursel Allenstein, ist sein erstes Buch auf Deutsch. Der bisher jüngste Preisträger des Literaturpreises des Nordischen Rats legt Erzählungen mit mitunter brutaler Körperlichkeit vor, die in einer von ökonomischen Begierden durchzogenen Gesellschaft spielen und wie selbstverständlich in Welten führen, die mit einem simplen Realitätsbegriff nicht immer zu fassen sind. -

French Performance Practices in the Piano Works of Maurice Ravel

Studies in Pianistic Sonority, Nuance and Expression: French Performance Practices in the Piano Works of Maurice Ravel Iwan Llewelyn-Jones Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy School of Music Cardiff University 2016 Abstract This thesis traces the development of Maurice Ravel’s pianism in relation to sonority, nuance and expression by addressing four main areas of research that have remained largely unexplored within Ravel scholarship: the origins of Ravel’s pianism and influences to which he was exposed during his formative training; his exploration of innovative pianistic techniques with particular reference to thumb deployment; his activities as performer and teacher, and role in defining a performance tradition for his piano works; his place in the French pianistic canon. Identifying the main research questions addressed in this study, an Introduction outlines the dissertation content, explains the criteria and objectives for the performance component (Public Recital) and concludes with a literature review. Chapter 1 explores the pianistic techniques Ravel acquired during his formative training, and considers how his study of specific works from the nineteenth-century piano repertory shaped and influenced his compositional style and pianism. Chapter 2 discusses Ravel’s implementation of his idiosyncratic ‘strangler’ thumbs as articulators of melodic, harmonic, rhythmic and textural material in selected piano works. Ravel’s role in defining a performance tradition for his piano works as disseminated to succeeding generations of pianists is addressed in Chapter 3, while Chapters 4 and 5 evaluate Ravel’s impact upon twentieth-century French pianism through considering how leading French piano pedagogues and performers responded to his trailblazing piano techniques. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>2 GREAT BRITAIN: ffrr, 1944-57 In a business where exclusive contracts were the norm, it was very difficult for a newcomer to become established and Decca’s initial roster of classical artists was unable to compete with established rivals. In March 1932 an agreement with Polydor provided access to a substantial catalogue of German artists and a year later the company virtually abandoned classical recording to concentrate on dance bands. The move to Thames Street Studios provided more scope for orchestral sessions and a bold policy of recording contemporary British music enhanced the label’s reputation. The newly formed Boyd Neel Orchestra was signed up in 1934, followed by the Griller String Quartet in 1935, Clifford Curzon in 1937, Peter Pears in 1944, Kathleen Ferrier in 1946 and Julius Katchen in 1947. War broke the link with Polydor, leaving Decca with a respectable catalogue of chamber music, but little symphonic repertoire. Armed with ffrr technology, the company began to remedy this in 1944, engaging Sidney Beer’s National Symphony Orchestra until 1947 and the misleadingly named New Symphony Orchestra (it had made its first recordings in 1909) from 1948. Neither developed into a house band to rival EMI’s Philharmonia and, with the Royal Philharmonic also exclusive to EMI, Decca had to resort to the LSO and the LPO, both in rather run-down condition in the post-war years. Meanwhile every opportunity was taken to impress visiting continental orchestras with ffrr sessions and it was evident that the company intended to transfer much of its symphonic work to Paris, Amsterdam, Geneva and Vienna as soon as practicable. -

Montag, 17.08.2020 17

Montag, 17.08.2020 17. August 1955 - Das Leitung: Herbert Kegel Gesetz über das ab 02:03: Kassenarztrecht wird Ottorino Respighi: verabschiedet Feste romane; New York 10:50 WDR 2 - Wilfried Philharmonic, Leitung: Schmickler Giuseppe Sinopoli 13:00 WDR 2 Das Robert Fuchs: 00:00 1LIVE Fiehe Mittagsmagazin Streicherserenade e-Moll, Freestylesendung mit Klaus Darin: op. 21; Kölner Kammerorchester, Leitung: Fiehe zur vollen Stunde WDR seit 22:00 Uhr aktuell Christian Ludwig Erich Wolfgang Korngold: 01:00 Die junge Nacht der ARD zur halben Stunde WDR aktuell und Lokalzeit auf Sextett D-Dur, op. 10; Mit Lara Heinz Thomas Selditz, Viola; Darin: WDR 2 Màrius Díaz, Violoncello; zur vollen Stunde WDR 15:00 WDR 2 Der Nachmittag Aron Quartett aktuell Darin: Michail Ippolitow-Iwanow: 05:00 1LIVE mit Donya Farahani zur vollen Stunde WDR aktuell Sinfonie Nr. 1 e-Moll, op. 46; und dem Bursche zur halben Stunde bis 17:30 Bamberger Symphoniker, Die tägliche, aktuelle Leitung: Gary Brain Morgen-Show in 1LIVE WDR aktuell und Lokalzeit auf WDR 2 ab 04:03: 10:00 1LIVE Tina Middendorf 18:40 WDR 2 Stichtag Antonín Dvořák: Der Vormittag in 1LIVE (Wiederholung von 09:40) Die Waldtaube, op. 110; 14:00 1LIVE Kammel und Kühler 19:00 WDR 2 Jörg Thadeusz Münchner Der Nachmittag in 1LIVE Darin: Rundfunkorchester, Leitung: 18:00 1LIVE mit Lisa Kestel zur vollen Stunde WDR Peter Gülke Die Themen des Tages im aktuell Johann Sebastian Bach: Sektor Suite G-Dur, BWV 1007; 20:00 WDR 2 POP! Pieter Wispelwey, 20:00 1LIVE Plan B Darin: Der Abend in 1LIVE - im zur vollen Stunde WDR Violoncello Nikolaj Rimskij-Korsakow: Zeichen der Popkultur aktuell Mit Tilmann Köllner Konzert-Fantasie h-Moll, op. -

Lodge News July 2019

Lodge Waikato 475 OF FREE AND ACCEPTED FREEMASONS JULY 2019 P L U M B L I N E Students from Ngaruawahia High-school Havana Klink and Adam Kimpton with Mrs Kimpton. Recipients of financial assistance to enable them to attend ‘ O utward Bound ’ “ O utdoor Challenge and Adventure Teen Course. ” NOTICE PAPER MASTER W.Bro. Graham Hallam 40 Wymer Terrace, Hamilton PH. 07 855 5198 027 855 5198 SENIOR WARDEN JUNIOR WARDEN W.Bro Adrian de Bruin W.Bro Andre Schenk 265A Hakirimata Rd 11 Beaufort Place Ngaruawahia Flagstaff, Hamilton. Ph. 07 824 7234 ( eve ) Ph 027 5784 060 TREASURER SECRETARY W.Bro. Alan Harrop W.Bro. Bill Newell 18 Cherrywood St Villa 19 - St. Kilda Retirement Village Pukete, Hamilton 91 Alan Livingstone Drive, Cambridge, Ph 027 499 5733 021 061 8828 Dear Brother, You are hereby summoned to attend the Regular Monthly Meeting of Lodge Waikato, to be held in the Hamilton East Masonic Centre, Grey St., Hamilton East , on Thursday 18th July 2019 at 6.30pm Ceremony: - Lodge - .Installation - W.Bro Adrian de Bruin 1. Confirmation of Minutes 2. Accounts payable 3. Treasurer ’ s report 4. Correspondence 5. Almoner ’ s report 6. General Business 7. Notice of Motion W.Bro Bill Newell - Hon Sec Officers of the Lodge I.P.M. - W.Bro Willy Willetts Dep. Master - W.Bro Bob Ancell Sen. Deacon - Bro Trevor Langley Jun. Deacon - W.Bro Dennis Mead Chaplain - W.Bro John Dickson Almoner - W.Bro Graham Hallam Secretary - W.Bro Bill Newell Ass Secretary - W.Bro John Evered Dir. of Ceremony - W.Bro Don McNaughton Ass.