Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Il Settore Tessile-Abbigliamento

JUNIOR FASHION IN 2019-2020 Notes by CONFINDUSTRIA MODA - Centro Studi for The preliminary balance-sheet for 2019 According to preliminary estimates by Centro Studi of Confindustria Moda for SMI, total Junior Fashion is turnover of Junior Fashion (understood as fabric and knit clothing for children in the 0 to 14 forecast to have closed the year 2019 age range, including intimate apparel and accessories) saw a continuation of the positive with a 3.5% increase in turnover. trend. Even though the rhythms were more subdued than those that typified the year 2018, industry sales should close the year 2019 with a +3.5% increase and thus top the 3 billion euro mark. The value of production (a variable which, you will recall, aims to quantify the value of domestic production net marketing of imported products) is expected to close down, with a -2.6% estimated loss. Table 1 – The Italian Junior Clothing Industry (2014-2019*)(1) (Millions euro at current value) 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019* Sales 2.642 2.687 2.762 2.861 2.980 3.083 % Var. 1,7 2,8 3,6 4,2 3,5 Value of Production 1.029 980 977 969 943 918 % Var. -4,8 -0,3 -0,7 -2,8 -2,6 Exports 947 997 1.041 1.102 1.196 1.269 Var. % 5,3 4,4 5,9 8,5 6,1 Imports 1.675 1.787 1.777 1.787 1.974 2.119 % Var. 6,7 -0,6 0,6 10,4 7,4 Trade Balance -728 -790 -737 -685 -777 -850 End Consumption 4.284 4.256 4.246 4.236 4.155 4.083 % Var. -

PITTI UOMO 96 Presents Men’S Fashion & Lifestyle Collections for S/S 2020

U 96 PITTI UOMO 96 Presents Men’s fashion & lifestyle collections for S/S 2020 itti Uomo 96, the leading global trade fair dedicated to The Pitti Special Click menswear and contemporary lifestyles, will be held in The theme of the Pitti Immagine summer fairs PFlorence which was held at Fortezza da Basso from June Something Special Clicks into place every six months at the Pitti Immagine fairs 11-14, 2019, confirmed itself as a global crossroads of trends, when the research carried out by brands and the Pitti team into new projects, novelties and launches of new projects for men's fashion and events and international names faces off with the research of buyers, journalists, lifestyle. A total of 30,000 visitors and over 18,500 buyers arrived influencers and visitors from all over the world. The resulting sparks produce an in Florence from 100 foreign countries, for an edition full of energy always new energy and emotions together with a certain “X Factor” that made each encounter a success and made people eager to come to Florence in order to and optimism. Some important markets such as France, Turkey, see, learn and try to understand. This is The Pitti Special Click, the theme of this Hong Kong, Belgium and Russia were performing well, whereas summer’s fairs which sums up the energy that circulates around the Fortezza and buyers from China, Germany, Spain, Japan and those of Italian suddenly finds a direction. The Main Forecourt of the Fortezza da Basso was once buyers were slightly down. Germany ranked first in the top 15 again transformed through the set design curated by lifestyler Sergio Colantuoni. -

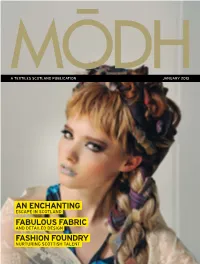

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

Paul Iribe (1883–1935) Was Born in Angoulême, France

4/11/2019 Bloomsbury Fashion Central - BLOOMSBURY~ Sign In: University of North Texas Personal FASHION CENTRAL ~ No Account? Sign Up About Browse Timelines Store Search Databases Advanced search --------The Berg Companion to Fashion eBook Valerie Steele (ed) Berg Fashion Library IRIBE, PAUL Michelle Tolini Finamore Pages: 429–430 Paul Iribe (1883–1935) was born in Angoulême, France. He started his career in illustration and design as a newspaper typographer and magazine illustrator at numerous Parisian journals and daily papers, including Le temps and Le rire. In 1906 Iribe collaborated with a number of avantgarde artists to create the satirical journal Le témoin, and his illustrations in this journal attracted the attention of the fashion designer Paul Poiret. Poiret commissioned Iribe to illustrate his first major dress collection in a 1908 portfolio entitled Les robes de Paul Poiret racontées par Paul Iribe . This limited edition publication (250 copies) was innovative in its use of vivid fauvist colors and the simplified lines and flattened planes of Japanese prints. To create the plates, Iribe utilized a hand coloring process called pochoir, in which bronze or zinc stencils are used to build up layers of color gradually. This publication, and others that followed, anticipated a revival of the fashion plate in a modernist style to reflect a newer, more streamlined fashionable silhouette. In 1911 the couturier Jeanne Paquin also hired Iribe , along with the illustrators Georges Lepape and Georges Barbier, to create a similar portfolio of her designs, entitled L’Eventail et la fourrure chez Paquin. Throughout the 1910s Iribe became further involved in fashion and added design for theater, interiors, and jewelry to his repertoire. -

Givenchy Exudes French Elegance at Expo Classic Luxury Brand Showcasing Latest Stylish Products for Chinese Customers

14 | FRANCE SPECIAL Wednesday, November 6, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY Givenchy exudes French elegance at expo Classic luxury brand showcasing latest stylish products for Chinese customers This lipstick is a tribute and hom Givenchy has made longstanding age to the first Rouge Couture lip ties with China and a fresh resonance stick created by Hubert James Taffin in the country. The Mini Eden bag (left) de Givenchy, which had a case and Mini Mystic engraved with multiples 4Gs. History of style handbag are Givenchy’s Thirty years after Givenchy Make The history of Givenchy is a centerpieces at the CIIE. up was created, these two shades also remarkable one. have engraved on them the same 4Gs. The House of Givenchy was found In 1952, Hubert James Taffin de ed by Hubert de Givenchy in 1952. Givenchy debuted a collection of “sep The name came to epitomize stylish arates” — elegant blouses and light elegance, and many celebrities of the skirts with architectural lines. Accom age made Hubert de Givenchy their panied by the most prominent designer of choice. designers of the time, he established When Hubert de Givenchy arrived new standards of elegance and in Paris from the small town of Beau launched his signature fragrance, vais at the age of 17, he knew he want L’Interdit. ed to make a career in fashion design. In 1988, Givenchy joined the He studied at the Ecole des Beaux LVMH Group, where the couturier Arts in Versailles and worked as an remained until he retired in 1995. assistant to the influential designer, Hubert de Givenchy passed away Jacques Fath. -

A Vision of Fashion from the Early 20Th Century to the Present Day

A Vision of Fashion Outline from the early 20th century to the present day This exhibition,"A Vision of Fashion: from the early 20th century to the present day" explores the history of fashion with fabulous exhibits. Mainly, out of the rich collections of the Kyoto Costume Institute (KCI), more than 100 outstanding items are selected for the show. The exhibition consists of dresses, corsets, and shoes. You will find items by distinguished designers including Worth, Chanel, Christian Dior, Yves Saint-Laurent, Issey Miyake, Comme des Garçons, and Yohji Yamamoto as well as designers of the new generation. Exhibited pieces Dresses: 85 pieces Corsets, shoes: 19 pieces Amount: 104 pieces Brand / Designers Azzedine Alaïa, Giorgio Armani, Pierre Balmain, Biba / Barbara Hulanicki, Bulloz, Pierre Cardin, Hussein Chalayan, Chanel, Chloé, Comme des Garçons / Rei Kawakubo, Courrèges, Christian Dior, ©The Kyoto Costume Institute Dorothée bis / Jacqueline Jacobson, Jacques Fath, Mariano Fortuny, Maria Monaci Gallenga, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Rudi Gernreich, Date: 25th of June to 4th of Sep., 2011 Romeo Gigli, Givenchy, Harry Gordon, Gucci, Emmanuelle Khanh Place: Contemporary Art Museum, Kumamoto diffusion Troisa, Tokio Kumagaï, Jeanne Lanvin, Yves Saint Organizer: Kumamoto City, Laurent, matohu / Hiroyuki Horihata, Makiko Sekiguchi, Kumamoto Art and Culture Promotion Foundation, mintdesigns / Hokuto Katsui, Nao Yagi, Issey Miyake, Molyneux, Kumamoto Nichinichi Press, TKU(TV Kumamoto) Thierry Mugler, Paul Poiret, Prada, Paco Rabanne, Sonia Rykiel, Curator: Takeshi Sakurai, MIKIO SAKABE / Mikio Sakabe, Shueh Jen-Fang, Schiaprelli, Contemporary Art Museum, Kumamoto Seditionaries, Madeleine Vionnet, Louis Vuitton, Junya Akiko Fukai, the Kyoto Costume Institute Watanabe,Vivienne Westwood, Worth,Yohji Yamamoto . -

Reflecting Noble Luxury and Refinement, New Lightweight Wool Materials Are of Key Interest to Designers, Retailers and Bespoke Tailors

Reflecting noble luxury and refinement, new lightweight wool materials are of key interest to designers, retailers and bespoke tailors. Beyond demanding perfected fits and wool’s signature aesthetic, discerning consumers expect emotional, sensorial tactility in garments. Responding to luxury market demands, leading Italian and English spinners and weavers are introducing exclusive fine-micron yarns and fabrics, derived from rare Australian merino. Stylesight explores Baruffa Group’s finest wool yarns for first-class sweater knits, cut-and-sew jersey, and wovens. Vogue Australia December 2012 / Elizabeth Debicki in wool, on location at Haddon Rig, a Merino wool farm in New South Wales. With seductive, magnetic charm, lighter weight but often still densely constructed wovens and knits are key on men and women's runways and at textile trade shows. Wool—traditionally a winter fiber—evolves with cutting-edge superfine qualities from 150s and 180s up to 250s. Offering noble refinement and unique trans-seasonal possibilities, wool moves beyond its pastime connotations. Gossamer knits / Posh mesh / Lightweight jerseys / Dense, hefty yet lightweight wools Finest wool Fabrics F/W 13 Dormeuil Limited Edition - finest wool yarns Zegna Baruffa Lane Record Bale - finest wool fabric Loro Piana Borgosesia Finest wool Fabrics Taylor & Lodge Meticulous fiber selection from choice breeds, along with revolutionary spinning and weaving technologies, is core to new noble wool productions. Wools characterized by strength, elasticity, fluidity, low pilling and -

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour a Practice

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour A Practice-Led Masters by Research Degree Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Discipline: Fashion Year of Submission: 2008 Key Words Male fashion Clothing design Gender Tailoring Clothing construction Dress reform Innovation Design process Contemporary menswear Fashion exhibition - 2 - Abstract Since the establishment of the first European fashion houses in the nineteenth century the male wardrobe has been continually appropriated by the fashion industry to the extent that every masculine garment has made its appearance in the female wardrobe. For the womenswear designer, menswear’s generic shapes are easily refitted and restyled to suit the prevailing fashionable silhouette. This, combined with a wealth of design detail and historical references, provides the cyclical female fashion system with an endless supply of “regular novelty” (Barthes, 2006, p.68). Yet, despite the wealth of inspiration and technique across both male and female clothing, the bias has largely been against menswear, with limited reciprocal benefit. Through an exploration of these concepts I propose to answer the question; how can I use womenswear patternmaking and construction technique to implement change in menswear design? - 3 - Statement of Original Authorship The work contained in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma at any other higher educational institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Signed: Mark L Neighbour Dated: - 4 - Acknowledgements I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone who supported and assisted this project. -

Weaving Twill Damask Fabric Using ‘Section- Scale- Stitch’ Harnessing

Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research Vol. 40, December 2015, pp. 356-362 Weaving twill damask fabric using ‘section- scale- stitch’ harnessing R G Panneerselvam 1, a, L Rathakrishnan2 & H L Vijayakumar3 1Department of Weaving, Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Chowkaghat, Varanasi 221 002, India 2Rural Industries and Management, Gandhigram Rural Institute, Gandhigram 624 302, India 3Army Institute of Fashion and Design, Bangalore 560 016, India Received 6 June 2014; revised received and accepted 30 July 2014 The possibility of weaving figured twill damask using the combination of ‘sectional-scaled- stitched’ (SSS) harnessing systems has been explored. Setting of sectional, pressure harness systems used in jacquard have been studied. The arrangements of weave marks of twill damask using the warp face and weft face twills of 4 threads have been analyzed. The different characteristics of the weave have been identified. The methodology of setting the jacquard harness along with healds has been derived corresponding to the weave analysis. It involves in making the harness / ends in two sections; one section is to increase the figuring capacity by scaling the harness and combining it with other section of simple stitching harnessing of ends. Hence, the new harness methodology has been named as ‘section-scale-stitch’ harnessing. The advantages of new SSS harnessing to weave figured twill damask have been recorded. It is observed that the new harnessing methodology has got the advantages like increased figuring capacity with the given jacquard, less strain on the ends and versatility to produce all range of products of twill damask. It is also found that the new harnessing is suitable to weave figured double cloth using interchanging double equal plain cloth, extra warp and extra weft weaving. -

Altman on Jacobs on Dior: Fashion Through Fractals and Archives

Streetnotes (2012) 20: 90-110 90 ISSN: 2159-2926 Altman on Jacobs on Dior: Fashion Through Fractals and Archives J. Emmanuel Raymundo Abstract On February 25, 2011, the fashion luxury company Christian Dior suspended John Galliano, who had been its creative director since 1996, after his arrest over making anti-Semitic remarks at a Paris bar. Quickly following his suspension, a video from December 2010 was distributed showing Galliano hurling anti-Semitic invectives at several bar patrons. On March 1, 2011, Dior fired Galliano. At stake in the considerable interest and speculations regarding who takes over at Dior is control of a €24.6B business empire and access to a historic couturier’s archive. In this sense, its designer will influence the label’s “books” both financial and what will be stored in its physical repository as part of the brand’s creative and artistic repertoire. Despite fashion’s apparent ubiquity, the anticipation surrounding who takes over at Dior is proof that despite fashion’s professed democratization, there still exists a fashion hierarchy with Dior occupying its upper echelon. Since Galliano’s dismissal, fashion insiders have moved from breathlessly feverish in their speculations to desperately calling out for relief in the face of an unexpectedly drawn-out waiting game that is now over a year old and otherwise an eternity in fashion’s hyper accelerated production cycle. To purposely counter fashion’s accelerated internal clock, the purpose of this commentary is to keep fashion in a reflective state rather than a reflexive stance and uses fashion on film, and specifically Robert Altman’s Prêt-à-Porter (1994), to give cultural and historical context to all the online speculation and chatter. -

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Weronika Gaudyn December 2018 STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART Weronika Gaudyn Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor School Director Mr. James Slowiak Mr. Neil Sapienza _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Ms. Lisa Lazar Linda Subich, Ph.D. _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Sandra Stansbery-Buckland, Ph.D. Chand Midha, Ph.D. _________________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Due to a change in purpose and structure of haute couture shows in the 1970s, the vision of couture shows as performance art was born. Through investigation of the elements of performance art, as well as its functions and characteristics, this study intends to determine how modern haute couture fashion shows relate to performance art and can operate under the definition of performance art. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee––James Slowiak, Sandra Stansbery Buckland and Lisa Lazar for their time during the completion of this thesis. It is something that could not have been accomplished without your help. A special thank you to my loving family and friends for their constant support -

T\\I Summit Bank, Pays Interest at 4Oio

THE CHATHAM Vol.. X. No. |s. CHATHAM, MMI;!;!.- Col.WTY, N. J., Fi.liKlAliV So, 1', $1.50 PER YEAR, LARGE REAL OBITUARY. FIVE OUT OF SIX Serious Acci ':n! to 'i'mine Girl. Mrs. 'Michael Ryan. > \i,, M.lili'i-,1 I Mrs. Michael Hyan died at her CHARLES MflNLEY ESTATE DEAL homo, on l.iun avenue last Friday FOR LOCAL BOYS lay night. She had been ailing fur si i i i ' ,i. .1 . , .: , i lung lime, but the end came unex- REAL ESTATE RHU IMSURAHCE Minion Tract of Over Thirty Acre; .lerts of Madison Never Had asail i'l HI HV..I. i, pectedly. She leaves her husband, a laughter, Man, and two sons, Aliens COMMISSIONER OF Dfc'cDS S Id .0 a N;w York Syndicate Look-in and Dropped Three Mil.l.vil .ill.-II.I, ,i us F. and John. Mrs. Hyan \va- Wh'ch Will Explut It. ibout sixty-five years old. She was Straight Games. „'! \ .'II in I iu rhaj.,1 ,,l I l.i- I i^. horn in Ireland, but eame to this .ui.il rli .i'i li W,',l.i,.,.l,v .'.i'i MAIN STREET CHATHAM I'lninuy when young. She has bem PROPERTY IS ON SUMMIT AV! a resident of Chatham for man TOCK TWO FROM ORANGE A. A. •„',IM ih. II >i IUI'IL i- •cars, and was a member of St. Pai- .•I II. l,. I ,1 -..-ll A re il c.-i'ii'i' .leal of largo iironor ilel.'s f'hnrrli. The fune'al service; Ihe loeal bowlers enlfiiati • ! th• |.