Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

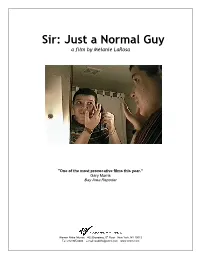

Sir: Just a Normal Guy a Film by Melanie Larosa

Sir: Just a Normal Guy a film by Melanie LaRosa "One of the most provocative films this year.” Gary Morris Bay Area Reporter Women Make Movies · 462 Broadway, 5th Floor · New York, NY 10013 Tel: 212.925.0606 · e-mail: [email protected] · www.wmm.com Sir: Just a Normal Guy Synopsis Screened to acclaim at Gay & Lesbian Film Festivals worldwide and LBGT events across the nation, this candid and courageous portrait of more than 15-months in the female-to-male (FTM) transition of Jay Snider explores both the emotional and physical changes of this profound experience--beginning prior to hormones and concluding after top surgery. Footage shot before and after the surgery captures dramatic physical transitions, while intimate interviews with Jay, his ex-husband, his best friend and his lesbian-identified partner aptly capture the emotional and psychological shifts that occur during the process. With support from those closest to him, Jay’s experience is remarkably positive, though not without conflict. During the course of the film, he renews long-distant ties with his brother, but also faces permanent estrangement from his parents. SIR: JUST A NORMAL GUY is an in-depth and humanizing exploration of the challenges, discrimination, and alienation faced by transsexuals. Jay’s conflicted feelings around queer identification are portrayed along with his significant other’s continued identification as lesbian. A much-needed look at FTM transition, the film demonstrates both the fluidity of sexual identification and that love and human resilience can triumph over deep-rooted differences. Festivals and Awards For the most updated list, visit www.wmm.com. -

MS and Grad Certificate in Human Rights

NEW ACADEMIC PROGRAM – IMPLEMENTATION REQUEST I. PROGRAM NAME, DESCRIPTION AND CIP CODE A. PROPOSED PROGRAM NAME AND DEGREE(S) TO BE OFFERED – for PhD programs indicate whether a terminal Master’s degree will also be offered. MA in Human Rights Practice (Online only) B. CIP CODE – go to the National Statistics for Education web site (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/browse.aspx?y=55) to select an appropriate CIP Code or contact Pam Coonan (621-0950) [email protected] for assistance. 30.9999 Multi-/Interdisciplinary Studies, Other. C. DEPARTMENT/UNIT AND COLLEGE – indicate the managing dept/unit and college for multi- interdisciplinary programs with multiple participating units/colleges. College of Social & Behavioral Sciences D. Campus and Location Offering – indicate on which campus(es) and at which location(s) this program will be offered (check all that apply). Degree is wholly online II. PURPOSE AND NATURE OF PROGRAM–Please describe the purpose and nature of your program and explain the ways in which it is similar to and different from similar programs at two public peer institutions. Please use the attached comparison chart to assist you. The MA in Human Rights Practice provides online graduate-level education for human rights workers, government personnel, and professionals from around the globe seeking to further their education in the area of human rights. It will also appeal to recent undergraduate students from the US and abroad with strong interests in studying social justice and human rights. The hallmarks of the proposed -

Insight Sociological

SICOVERfinal_Rev.pdf 5/18/09 9:50:53 AM Sociological Insight Volume 1 May 2009 1 May 2009 Volume The Effects of Religious Switching at Marriage on Marital Stability and Happiness Collin Payne Sociological A Tale of Two Townships: Political Opportunity and Violent and Non-Violent Local Control in South Africa Insight Volume 1 May 2009 Alex Park C M Sex Offender Recidivism in Minnesota and the Importance of Law and News Coverage Y Ashley Leyda CM Sociological Insight MY “Been There, Done That:” A Case Study of Structural Violence and Bureaucratic Barriers CY in an HIV Outreach Organization CMY Dayna Fondell K Style and Consumption among East African Muslim Immigrant Women: The Intersection of Religion, Ethnicity, and Minority Status Jennifer Barnes Pretty Dresses and Privilege: Gender and Heteronormativity in Weddings Alissa Tombaugh “That Synergy of People:” The Significance of Collective Identity and Framing in a Gay-Straight Coalition Tristine Baccam Research Note: Technological Prospects for Social Transformation: Sociology and the Freedom of Information Samuel J. Taylor Book Reviews Undergraduate Research Journal Sociological Insight Volume 1 May 2009 Volume 1 May 2009 Editor-in-Chief: Mazen Elfakhani Information for Contributors Managing Editors: Deva Cats-Baril, Noble Kuriakose Sociological Insight is a fully refereed research journal that publishes articles, research Deputy Editors: Laura Hudson, Micheondra Williams, Tabitha Spence notes, and book reviews on sociology and other social sciences. The journal aims to Layout Editor: Samuel Taylor attract and promote original undergraduate research of the highest quality without Cover Designer: Nancy Guevara regard to substantive focus, theoretical orientation, and methodological approach. Editorial Board Submission and Style Guidlines Christopher Ellison University of Texas at Austin Cynthia Buckley University of Texas at Austin Submit one electronic version of your manuscript to sociologicalinsight@austin. -

Jeanette L Buck [email protected]

Jeanette L Buck [email protected] CREATIVE WORK/Film and Theater Director Inheritance (short narrative film) in pre-production Winter 2019 Director Fall 2019 The Shoot (short narrative film) in post-production Co-Director Fall 2019 Rhinoceros by Eugene Ionesco Tantrum Theater, Athens, OH Director 2018 Defiance of Dandelions by Philana Omorotionmwan Ohio University, School of Theater, Athens, OH Director and Story By 2018 Heather Has Four Moms (short narrative trt 13:00) Festival Screenings: Athens International Film and Video Festival in Athens, OH April 11, 2018 Cinema Systers, Paducah, KY May 2018 *Award Best Short Film Dyke Drama, Perth, Australia May 2018 *Audience Award for Best Short Film Provincetown Film Festival, Provincetown, MA June 13-17, 2018 Out Here Now: Kansas City LGBT Film Festival, Kansas City, MO June 21-28, 2018 Female Eye Film Festival, Toronto, Canada June 26-July 1, 2018 Women in Film and Television Atlanta Short Film Showcase, Atlanta, GA July 30, 2018 Chain NYC Film Festival, Manhattan, New York August 10-19, 201 *Award for Writer of a Short Film North Carolina Gay and Lesbian Film Festival August 18-22, 2018 Broad Humor Film Festival, Venice, CA August 30- September 2, 2018 FM LGBT Film Festival, Fargo-Moorhead, ND/MN September 12-15, 2018 Sioux City International Film Festival, Sioux City, IA September 12-16, 2018 *Audience Choice Award LGBTQ Short Film Cinema Diverse: Palm Springs LGBTQ Film Festival September 20-23, 2018 Women Over 50 Film Festival, Brighton and Lewes, UK September 20- 23, 2018 Reeling: -

Supreme Court of the United States ______JOHN GEDDES LAWRENCE and TYRON GARNER Petitioners, V

No. 02-102 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _______________ JOHN GEDDES LAWRENCE AND TYRON GARNER Petitioners, v. STATE OF TEXAS, Respondent. _______________ On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Texas, Fourteenth District _______________ AMICUS BRIEF OF HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN; NA- TIONAL GAY & LESBIAN TASK FORCE; PARENTS, FAMILIES & FRIENDS OF LESBIANS & GAYS; NA- TIONAL CENTER FOR LESBIAN RIGHTS; GAY & LES- BIAN ADVOCATES & DEFENDERS; GAY & LESBIAN ALLIANCE AGAINST DEFAMATION; PRIDE AT WORK, AFL-CIO; PEOPLE FOR THE AMERICAN WAY FOUN- DATION; ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE; MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATION FUND; PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATION FUND; SOCIETY OF AMERICAN LAW TEACHERS; SOULFORCE; STONEWALL LAW ASSOCIATION OF GREATER HOUSTON; EQUALITY ALABAMA; EQUAL- ITY FLORIDA; S.A.V.E.; COMMUNITY CENTER OF IDAHO; YOUR FAMILY, FRIENDS & NEIGHBORS; KANSAS UNITY & PRIDE ALLIANCE; LOUISIANA ELECTORATE OF GAYS & LESBIANS; EQUALITY MISSISSIPPI; PROMO; NORTH CAROLINA GAY & LESBIAN ATTORNEYS; CIMARRON FOUNDATION OF OKLAHOMA; SOUTH CAROLINA GAY & LESBIAN PRIDE MOVEMENT; ALLIANCE FOR FULL ACCEP- TANCE; GAY & LESBIAN COMMUNITY CENTER OF UTAH; AND EQUALITY VIRGINIA IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS _______________ BRIAN V. ELLNER WALTER DELLINGER MATTHEW J. MERRICK (Counsel of Record) GAYLE E. POLLACK PAMELA HARRIS O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP JONATHAN D. HACKER Citigroup Center O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP 153 East 53rd Street 555 13th Street, N.W. New York, New York 10022 Washington, D.C. 20004 (212) 326-2000 (202) 383-5300 Attorneys for Amici Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................ ii INTEREST OF AMICI..........................................................1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................................1 ARGUMENT .........................................................................2 I. TEXAS’ HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT LAW IS A PRODUCT OF ANTI-GAY ANIMUS........................4 A. -

Family Pride Coalition

1 The DC Metropolitan Area has a variety of grassroots organization working with the Gay, Lesbians Bisexual, Transgender and Allies community. The following are a sample of organizations that deal with different issues facing the GLBT community. For more information, please contact the organization via website or phone. Brother Help Thyself Brother Help Thyself funds and nurtures nonprofit organizations serving the GLBTQ and HIV/AIDS communities in the Metro Baltimore / Washington areas. BHT is a community based foundation that accomplishes its mission by: Dispensing direct and matching grants to non-profit organizations, Acting as a clearinghouse for donated goods and services and Serving as an information resource to our community. Contact: [email protected] / 202.347.2246 / www.brotherhelpthyself.org 1111 14th Street, NW, Suite 350, Washington DC, 20005 Burgundy Crescent The purpose of Burgundy Crescent Volunteers (BCV) is twofold. First, they are a source of volunteers for local and national gay and gay-friendly community organizations in the Washington, DC area. Second, they bring gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender singles and couples together for volunteer activities that are social in nature. Contact: Jonathan Blumenthal / [email protected] / www.burgundycrescent.org DC Center: Home for GLBT in Metro DC (The Center) The Center was established and designed to support the GLBT communities within the DC/Metro areas. They develop programming to benefit the Metropolitan Washington GLBT community that involve advocacy, support programs, and community coherency. In addition, they host a variety of offices for other DC GLBT organizations. The center works closely with these organizations for political advocacy. Contact: 202.682.2245 / www.thedccenter.org / 1111 14th Street, NW, Suite 350, Washington DC, 20005 Different Avenues Different Avenues is a non-profit agency located in northeastern Washington, DC. -

Other Indicia of Animus Against LGBT People by State and Local

Chapter 14: Other Indicia of Animus Against LGBT People by State and Local Officials, 1980-Present In this chapter, we draw from the 50 state reports to provide a sample of comments made by state legislators, governors, judges, and other state and local policy makers and officials which show animus toward LGBT people. Such statements likely both deter LGBT people from seeking state and local government employment and cause them to be closeted if they are employed by public agencies. In addition, these statements often serve as indicia of why laws extending legal protections to LGBT people are opposed or repealed. As the United States Supreme Court has recognized, irrational discrimination is often signaled by indicators of bias, and bias is unacceptable as a substitute for legitimate governmental interests.1 “[N]egative attitudes or fear, unsubstantiated by factors which are properly cognizable…are not permissible bases” for governmental decision-making.2 This concern has special applicability to widespread and persistent negative attitudes toward gay and transgender minorities. As Justice O‟Connor stated in her concurring opinion in Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 580-82 (2003): We have consistently held…that some objectives, such as “a bare...desire to harm a politically unpopular group,” are not legitimate state interests. … Moral disapproval of this group [homosexuals], like a bare desire to harm the group, is an interest that is insufficient to satisfy rational basis review under the Equal Protection Clause. 1 Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett, 531 U.S. 356, 367 (2001). 2 Id. (quoting Cleburne v Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. -

May2019 - Volume 26 Issue 5

Lavender Notes Improving the lives of LGBTQ older adults Volunteer through community building, education, and advocacy. Donate with PayPal Celebrating 24+ years of service and positive change May2019 - Volume 26 Issue 5 Windsor Young Imagine being a closeted lesbian, newly-promoted to Air Force Staff Sergeant, being transferred to Japan during the 1960s and being told your new assignment includes “purging” unwanted lesbians and gay men from the military! That would qualify as much more than a conundrum – a personal dilemma of the fourth order. Such was one of the life-changing moments for this month’s “Stories of Our Lives” subject, Windsor Young. Born at Hartford Hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, on 20th September 1943, Windsor was the fifth of her father’s children and the second of her mother’s – ultimately the older sister to a two-years-younger brother who shared the same parents with her. Unfortunately, he died of an overdose in the early 1990s at the age of 46. “I had what would have to be called a fairly horrible childhood,” Windsor recalls. “My father was an alcoholic – and a very mean one, a man with a Jekyll and Hyde personality. He beat my mother constantly, particularly when he’d been drinking and became a monster. She finally got tired of that when I was about eight years old and took me and my brother from Connecticut to the Chicago area. Unfortunately, she let him know where we were; he followed us there and started beating her again!” By the time she was 16, Windsor took a strong stand with her mother. -

Not Your Usual 'Dracula'

October 23, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 19 | LGBT Life in Maryland EQMD Appoints Morgan Sheets as New Executive Director BY STEVE CHARING Equality Maryland, the state’s largest lgbt civil rights advocacy organization, announced on October 13 the appoint- ment of Morgan Sheets as its new Executive Director. Ms. Sheets was chosen by the Board of Directors fol- lowing an extensive national search. A resident of Ellicott City, she comes to Equality Maryland after serving as the Director of Government Relations & Public Policy of the Amputee Coali- tion of America. “We are thrilled to have found someone of Morgan’s experience, caliber and knowledge,” said Equality Maryland Board President Scott Dav- enport in a statement. “Morgan brings commitment, determination, commu- nity awareness, communication and fundraising know-how, along with po- litical savvy to her life’s work as a non- Photo: Andriy Portyanko profit advocacy leader. “Her many years of executive ex- high school. I was doing theater and musicals perience at the helm of state-wide and Not Your Usual ‘Dracula’ and stuff. I took a dance class at some point, national progressive organizations and it just sort of snowballed pretty quickly. and issue campaigns, ability to build Choreographer Scott Rink returns to Three years later I was at Julliard, and was quick rapport with the community, and offered a job straight away with Eliot Feld knowledge of the political and social Baltimore with a new spooky production. and his company. I haven’t stopped dancing landscapes in Maryland makes her an since. I just went from one company to the ideal leader for the lgbt and straight BY JOSH ATEROVIS the Baltimore area. -

EPK 8.23.12 Updated

FESTIVAL SCREENINGS The 2011 Sundance Film Festival, Park City, Utah *WORLD PREMIERE* Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City *GOTHAM AWARD NOMINEE! Best Movie Not Playing At A Theater Near You* International Women’s Film Festival in Seoul (IWFFIS) Korea The Sarasota Film Festival, Florida The Nashville International Film Festival, Tennessee The Atlanta Film Festival, Georgia The Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival, Hawaii *WINNER! Best Feature Film Award* The Toronto Inside Out Film Festival, Canada *WOMEN’S SPOTLIGHT FEATURE* Bent Lens Cinema, Boulder, Colorado The Provincetown Film Festival, Massachusetts Rooftop Films 2011 Summer Series, New York City Frameline International LGBT Film Festival, San Francisco *WINNER! Honorable Mention: Best First Feature* The Kansas City Gay and Lesbian Film Festival The Galway Film Fleadh, Ireland The Philadelphia Q Fest *Opening Night Film!* Outfest: The Los Angeles LGBT Film Festival *WINNER! Special Programming Award* Newfest: The New York Gay and Lesbian Film Festival The Vancouver Queer Film Festival Oslo Gay and Lesbian Film Festival 17th Athens International Film Festival, Greece Colorado Springs Pikes Peak Lavender Film Festival *CLOSING NIGHT FILM* Citizen Jane Film Festival, Missouri Norrköping Flimmer Film Festival, Sweden Portland Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, Oregon Tampa International Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, Florida *WOMEN’S GALA FILM* eQuality Film Festival 2011, Albany, NY Southwest Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, Albuquerque, New Mexico Reel Affirmations Film Festival, Washington, -

DOCUMENTING QUEER VOICES in the SOUTH by Ashley D. Cole A

“I WANTED TO BE JUST WHAT I WAS:” DOCUMENTING QUEER VOICES IN THE SOUTH by Ashley D. Cole A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History Middle Tennessee State University December 2016 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kelly Kolar, Chair Dr. Pippa Holloway ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Kelly Kolar for her guidance and patience with me during my extended stay in the Public History program at MTSU. Dr. Kolar has continuously offered support and encouragement throughout my thesis writing process. She has been dedicated to the completion of this thesis, even when I was not. Dr. Pippa Holloway has also been an invaluable resource for developing my historiographical background for this thesis. Completion of this program would not have been possible without the love, support, and encouragement of my parents, Valorie and Curt Cole. I am so grateful to them for continuously helping me in my educational endeavors (and throughout my life in general). Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Rachel Rogers, for reading drafts even when she would rather not, for being my constant cheerleader, and for providing me with the stability and support to pursue my academic career. Rachel has been a source of inspiration for this thesis in that she lives authentically and lets her queer Southern voice be heard, even when met with resistance and rejection from those whom she loves. ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores themes in queer history and the concept of archival activism to argue for development of LGBT archival collections in the South that adequately reflect the region. -

1 Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. and Equality

Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. and Equality Mississippi hereby file this ethics complaint against George County Justice Court Judge Connie Glenn Wilkerson. Lambda Legal is an organization that currently represents lesbian parents and other litigants before Mississippi judges, and that will continue to represent lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) clients in Mississippi courts. Equality Mississippi is an organization dedicated to working to advance the cause of full equality and civil rights for all members of the Mississippi LGBT community. Judge Wilkerson has violated his ethical duties as set forth in Canons 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 of the Mississippi Code of Judicial Conduct by two separate actions. First, Judge Wilkerson wrote a letter to the editor of the George County Times, published March 28, 2002, in which he publicly stated that gay and lesbian people belong in mental institutions, advocated a position against legislation that advances civil rights for lesbian and gay people, and further stated that those elected officials who support such legislation and citizens who vote for said officials “have to stand in the judgment of GOD.” Second, on April 9, 2002, Judge Wilkerson stated, in an interview with Mississippi Public Radio, that gay and lesbian people are “sick.” The full text of Judge Wilkerson’s letter to the editor reads: Dear Editor: I got sick on my stomach today as I read the (AP) news story on the Dog attack on the front page of THE MISSISSIPPI PRESS and had to respond! AMERICA IS IN TROUBLE! I never thought that we would see the day when such would be here in AMERICA.