Development, Sexual Rights and Global Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

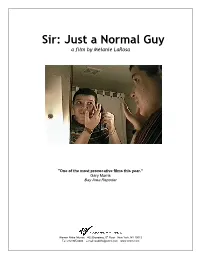

Sir: Just a Normal Guy a Film by Melanie Larosa

Sir: Just a Normal Guy a film by Melanie LaRosa "One of the most provocative films this year.” Gary Morris Bay Area Reporter Women Make Movies · 462 Broadway, 5th Floor · New York, NY 10013 Tel: 212.925.0606 · e-mail: [email protected] · www.wmm.com Sir: Just a Normal Guy Synopsis Screened to acclaim at Gay & Lesbian Film Festivals worldwide and LBGT events across the nation, this candid and courageous portrait of more than 15-months in the female-to-male (FTM) transition of Jay Snider explores both the emotional and physical changes of this profound experience--beginning prior to hormones and concluding after top surgery. Footage shot before and after the surgery captures dramatic physical transitions, while intimate interviews with Jay, his ex-husband, his best friend and his lesbian-identified partner aptly capture the emotional and psychological shifts that occur during the process. With support from those closest to him, Jay’s experience is remarkably positive, though not without conflict. During the course of the film, he renews long-distant ties with his brother, but also faces permanent estrangement from his parents. SIR: JUST A NORMAL GUY is an in-depth and humanizing exploration of the challenges, discrimination, and alienation faced by transsexuals. Jay’s conflicted feelings around queer identification are portrayed along with his significant other’s continued identification as lesbian. A much-needed look at FTM transition, the film demonstrates both the fluidity of sexual identification and that love and human resilience can triumph over deep-rooted differences. Festivals and Awards For the most updated list, visit www.wmm.com. -

MS and Grad Certificate in Human Rights

NEW ACADEMIC PROGRAM – IMPLEMENTATION REQUEST I. PROGRAM NAME, DESCRIPTION AND CIP CODE A. PROPOSED PROGRAM NAME AND DEGREE(S) TO BE OFFERED – for PhD programs indicate whether a terminal Master’s degree will also be offered. MA in Human Rights Practice (Online only) B. CIP CODE – go to the National Statistics for Education web site (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/browse.aspx?y=55) to select an appropriate CIP Code or contact Pam Coonan (621-0950) [email protected] for assistance. 30.9999 Multi-/Interdisciplinary Studies, Other. C. DEPARTMENT/UNIT AND COLLEGE – indicate the managing dept/unit and college for multi- interdisciplinary programs with multiple participating units/colleges. College of Social & Behavioral Sciences D. Campus and Location Offering – indicate on which campus(es) and at which location(s) this program will be offered (check all that apply). Degree is wholly online II. PURPOSE AND NATURE OF PROGRAM–Please describe the purpose and nature of your program and explain the ways in which it is similar to and different from similar programs at two public peer institutions. Please use the attached comparison chart to assist you. The MA in Human Rights Practice provides online graduate-level education for human rights workers, government personnel, and professionals from around the globe seeking to further their education in the area of human rights. It will also appeal to recent undergraduate students from the US and abroad with strong interests in studying social justice and human rights. The hallmarks of the proposed -

Jeanette L Buck [email protected]

Jeanette L Buck [email protected] CREATIVE WORK/Film and Theater Director Inheritance (short narrative film) in pre-production Winter 2019 Director Fall 2019 The Shoot (short narrative film) in post-production Co-Director Fall 2019 Rhinoceros by Eugene Ionesco Tantrum Theater, Athens, OH Director 2018 Defiance of Dandelions by Philana Omorotionmwan Ohio University, School of Theater, Athens, OH Director and Story By 2018 Heather Has Four Moms (short narrative trt 13:00) Festival Screenings: Athens International Film and Video Festival in Athens, OH April 11, 2018 Cinema Systers, Paducah, KY May 2018 *Award Best Short Film Dyke Drama, Perth, Australia May 2018 *Audience Award for Best Short Film Provincetown Film Festival, Provincetown, MA June 13-17, 2018 Out Here Now: Kansas City LGBT Film Festival, Kansas City, MO June 21-28, 2018 Female Eye Film Festival, Toronto, Canada June 26-July 1, 2018 Women in Film and Television Atlanta Short Film Showcase, Atlanta, GA July 30, 2018 Chain NYC Film Festival, Manhattan, New York August 10-19, 201 *Award for Writer of a Short Film North Carolina Gay and Lesbian Film Festival August 18-22, 2018 Broad Humor Film Festival, Venice, CA August 30- September 2, 2018 FM LGBT Film Festival, Fargo-Moorhead, ND/MN September 12-15, 2018 Sioux City International Film Festival, Sioux City, IA September 12-16, 2018 *Audience Choice Award LGBTQ Short Film Cinema Diverse: Palm Springs LGBTQ Film Festival September 20-23, 2018 Women Over 50 Film Festival, Brighton and Lewes, UK September 20- 23, 2018 Reeling: -

Family Pride Coalition

1 The DC Metropolitan Area has a variety of grassroots organization working with the Gay, Lesbians Bisexual, Transgender and Allies community. The following are a sample of organizations that deal with different issues facing the GLBT community. For more information, please contact the organization via website or phone. Brother Help Thyself Brother Help Thyself funds and nurtures nonprofit organizations serving the GLBTQ and HIV/AIDS communities in the Metro Baltimore / Washington areas. BHT is a community based foundation that accomplishes its mission by: Dispensing direct and matching grants to non-profit organizations, Acting as a clearinghouse for donated goods and services and Serving as an information resource to our community. Contact: [email protected] / 202.347.2246 / www.brotherhelpthyself.org 1111 14th Street, NW, Suite 350, Washington DC, 20005 Burgundy Crescent The purpose of Burgundy Crescent Volunteers (BCV) is twofold. First, they are a source of volunteers for local and national gay and gay-friendly community organizations in the Washington, DC area. Second, they bring gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender singles and couples together for volunteer activities that are social in nature. Contact: Jonathan Blumenthal / [email protected] / www.burgundycrescent.org DC Center: Home for GLBT in Metro DC (The Center) The Center was established and designed to support the GLBT communities within the DC/Metro areas. They develop programming to benefit the Metropolitan Washington GLBT community that involve advocacy, support programs, and community coherency. In addition, they host a variety of offices for other DC GLBT organizations. The center works closely with these organizations for political advocacy. Contact: 202.682.2245 / www.thedccenter.org / 1111 14th Street, NW, Suite 350, Washington DC, 20005 Different Avenues Different Avenues is a non-profit agency located in northeastern Washington, DC. -

May2019 - Volume 26 Issue 5

Lavender Notes Improving the lives of LGBTQ older adults Volunteer through community building, education, and advocacy. Donate with PayPal Celebrating 24+ years of service and positive change May2019 - Volume 26 Issue 5 Windsor Young Imagine being a closeted lesbian, newly-promoted to Air Force Staff Sergeant, being transferred to Japan during the 1960s and being told your new assignment includes “purging” unwanted lesbians and gay men from the military! That would qualify as much more than a conundrum – a personal dilemma of the fourth order. Such was one of the life-changing moments for this month’s “Stories of Our Lives” subject, Windsor Young. Born at Hartford Hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, on 20th September 1943, Windsor was the fifth of her father’s children and the second of her mother’s – ultimately the older sister to a two-years-younger brother who shared the same parents with her. Unfortunately, he died of an overdose in the early 1990s at the age of 46. “I had what would have to be called a fairly horrible childhood,” Windsor recalls. “My father was an alcoholic – and a very mean one, a man with a Jekyll and Hyde personality. He beat my mother constantly, particularly when he’d been drinking and became a monster. She finally got tired of that when I was about eight years old and took me and my brother from Connecticut to the Chicago area. Unfortunately, she let him know where we were; he followed us there and started beating her again!” By the time she was 16, Windsor took a strong stand with her mother. -

Not Your Usual 'Dracula'

October 23, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 19 | LGBT Life in Maryland EQMD Appoints Morgan Sheets as New Executive Director BY STEVE CHARING Equality Maryland, the state’s largest lgbt civil rights advocacy organization, announced on October 13 the appoint- ment of Morgan Sheets as its new Executive Director. Ms. Sheets was chosen by the Board of Directors fol- lowing an extensive national search. A resident of Ellicott City, she comes to Equality Maryland after serving as the Director of Government Relations & Public Policy of the Amputee Coali- tion of America. “We are thrilled to have found someone of Morgan’s experience, caliber and knowledge,” said Equality Maryland Board President Scott Dav- enport in a statement. “Morgan brings commitment, determination, commu- nity awareness, communication and fundraising know-how, along with po- litical savvy to her life’s work as a non- Photo: Andriy Portyanko profit advocacy leader. “Her many years of executive ex- high school. I was doing theater and musicals perience at the helm of state-wide and Not Your Usual ‘Dracula’ and stuff. I took a dance class at some point, national progressive organizations and it just sort of snowballed pretty quickly. and issue campaigns, ability to build Choreographer Scott Rink returns to Three years later I was at Julliard, and was quick rapport with the community, and offered a job straight away with Eliot Feld knowledge of the political and social Baltimore with a new spooky production. and his company. I haven’t stopped dancing landscapes in Maryland makes her an since. I just went from one company to the ideal leader for the lgbt and straight BY JOSH ATEROVIS the Baltimore area. -

EPK 8.23.12 Updated

FESTIVAL SCREENINGS The 2011 Sundance Film Festival, Park City, Utah *WORLD PREMIERE* Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City *GOTHAM AWARD NOMINEE! Best Movie Not Playing At A Theater Near You* International Women’s Film Festival in Seoul (IWFFIS) Korea The Sarasota Film Festival, Florida The Nashville International Film Festival, Tennessee The Atlanta Film Festival, Georgia The Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival, Hawaii *WINNER! Best Feature Film Award* The Toronto Inside Out Film Festival, Canada *WOMEN’S SPOTLIGHT FEATURE* Bent Lens Cinema, Boulder, Colorado The Provincetown Film Festival, Massachusetts Rooftop Films 2011 Summer Series, New York City Frameline International LGBT Film Festival, San Francisco *WINNER! Honorable Mention: Best First Feature* The Kansas City Gay and Lesbian Film Festival The Galway Film Fleadh, Ireland The Philadelphia Q Fest *Opening Night Film!* Outfest: The Los Angeles LGBT Film Festival *WINNER! Special Programming Award* Newfest: The New York Gay and Lesbian Film Festival The Vancouver Queer Film Festival Oslo Gay and Lesbian Film Festival 17th Athens International Film Festival, Greece Colorado Springs Pikes Peak Lavender Film Festival *CLOSING NIGHT FILM* Citizen Jane Film Festival, Missouri Norrköping Flimmer Film Festival, Sweden Portland Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, Oregon Tampa International Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, Florida *WOMEN’S GALA FILM* eQuality Film Festival 2011, Albany, NY Southwest Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, Albuquerque, New Mexico Reel Affirmations Film Festival, Washington, -

Book 1 Wdc4.Indb

© Lonely Planet INDEX See also separate Appalachian Trail 226, 227 Bill of Rights 62, 81, 89-90 Carroll, Kenny 50, 194 indexes for: aquariums 227 birds 39-40, 231 Carter, Jimmy 28 Arts p258 architecture 37-9, 67, see bird-watching 123, 231, 233 Cashion, Ann 163 also Sights subindex Black History Month 12 cathedrals, see Sights Eating p258 area codes, see inside front Blackwater National subindex Nightlife p259 cover Wildlife Refuge 231 caving, see Sports & Shopping p260 Arlington 121-4, 122, see boat travel, see Sports & Activities subindex Sights p260 also Northern Virginia Activities subindex cemeteries, see Sights Sleeping p262 accommodations 215 bocce 198 subindex Sports & food 168-9 Bonus Army 44 chemists 243-4 Activities p263 internet resources 121 books 20, 30-2, see also Cherry Blossom 10-Mile Top Picks p263 nightlife 185-6 Shopping subindex Run 13 Arlington National Booth, John Wilkes 23, 91 Cherry Blossom Festival 13 Cemetery 121 Brown, Dan 32 Chesapeake Bay 229-32, 8 A Armstrong, Louis 34, 111 Brown, John 23, 226 children, travel with 7, 116, accommodations 202-16, art galleries 29-30, 188-90 Buben, Jeff 155, 160-1 241, see also Shopping & see also Sleeping subindex see also Arts & Sights buildings, see Sights Sleeping subindexes bookings 203, 212 subindexes subindex Chinatown 86, 87, 92-3 activities 196-200, see Arthur M Sackler Gallery Bunshaft, Gordon 38 Chincoteague 232 also Sports & Activities 38-9 bus travel 237 Chincoteague National subindex & individual arts 29-37, 188-94, see Bush, George W 28-9, 43 Wildlife Refuge -

Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections

Legacy Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 What are Finding Aids? Finding aids are narrative guides to archival collections created by the repository to describe the contents of the material. They often provide much more detailed information than can be found in individual catalog records. Contents of finding aids often include short biographies or histories, processing notes, information about the size, scope, and material types included in the collection, guidance on how to navigate the collection, and an index to box and folder contents. What are Legacy Finding Aids? The following document is a legacy finding aid – a guide which has not been updated recently. Information may be outdated, such as the Historical Society’s contact information or exact box numbers for contents’ location within the collection. Legacy finding aids are a product of their times; language and terms may not reflect the Historical Society’s commitment to culturally sensitive and anti-racist language. This guide is provided in “as is” condition for immediate use by the public. This file will be replaced with an updated version when available. To learn more, please Visit DCHistory.org Email the Kiplinger Research Library at [email protected] (preferred) Call the Kiplinger Research Library at 202-516-1363 ext. 302 The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation’s capital. Founded in 1894, it serves a diverse audience through its collections, public programs, exhibits, and publications. 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. -

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the American Film Institute

CONTENTS AFI AND MONTGOMERY COLLEGE 2 AFI and Montgomery College BE A STUDENT AGAIN—AT ANY AGE! J’ai Été Au Bal/I Went to the Dance Join us at AFI Silver Theatre for these special educational screenings, each of which is followed by a discussion with a film Brian Henson/The Future of Digital professor from Montgomery College. Screenings are on Wednesdays and begin at 6:30. For students with valid ID, discount Puppetry tickets are available for only $6. RASHOMON*, Sept. 24 KNIFE IN THE WATER*, Oct. 29 BEAUTY AND THE BEAST*, Nov. 19 3 XIX Latin American Film Festival CHOP SHOP, Oct. 15 KISS OF DEATH, Nov. 5 LORD OF THE FLIES*, Dec. 3 * part of Janus Films Presents: Essential Art House Vol. 1 8 DC Labor FilmFest JANUS FILMS PRESENTS: ESSENTIAL ART HOUSE VOL. 1 10 Noir City DC Part of this semester's Montgomery College lineup comes courtesy of Janus Films, who, in partnership with the Criterion Collection, will be 12 Three by Antonioni launching the new DVD brand, Essential Art House. For the devoted cinephile, these are the must-see fundamentals; for the novice film-lover, this is precisely where to begin. 13 Halloween on Screen (Film notes courtesy of the Criterion Collection. Showtimes marked with an asterisk are part of the Montgomery College educational screenings.) 14 SILVERDOCS Presents RASHOMON About AFI Sat, Sept 13, 7:00; Sun, Sept 14, 3:00; Mon, Sept 15, 9:30; Tues, Sept 16, 7:00; Wed, Sept 24, 6:30* The murder of a man and the rape of his wife in a forest grove—seen from 15 Repertory Calendar – Full Schedule four different perspectives. -

Some Ground to Stand On

PRESS KIT SOME GROUND TO STAND ON 1998, 35 minutes, Color, Video This compelling and beautifully made documentary tells the life story of Blue Lunden, a working class lesbian activist whose odyssey of personal transformation parallels lesbian women's changing roles over the past 40 years. Starting with Blue's experience of being run out of town after her arrest in the 1950's New Orleans bar scene for wearing men's clothing, Some Ground to Stand On combines interviews, rare photos and archival footage to trace her life: giving up her child for adoption and getting her back; becoming sober; and coming into her own as a lesbian rights feminist, and anti-nuclear activist and lecturer. Now 61, Blue continues to be an activist as she reflects on aging, activism and a personal and generational struggle for "some ground to stand on" - a lesbian identity and consciousness rooted in community. • Washington DC Gay & Lesbian Film Festival— Audience Award • Black Maria Film Festival— Director's Choice Award • National Education Media Awards Festival— Bronze Apple Award • Reel Affirmations— Audience Choice Award • New York, San Francisco, London and Philadelphia Lesbian & Gay Film Festivals • New Orleans Film Festival • Rocky Mountain Women's Film Festival • Silver Image Festival • Reel NY— Channel Thirteen "The story of an astoundingly brave and persistent woman…it is the story of four decades of passionate engagement. This is a film that will help us remember what we must not forget." Joan Nestle, Lesbian Herstory Archives “A stirring film which presents her life and work vividly, powerfully, beautifully. Warshow's film of love, concern and power celebrates America's dykes across the decades." Blance Weisen Cook, Author CREDITS PRODUCER/DIRECTOR Joyce P. -

Bruce Majors

From: Bruce Majors <[email protected]> Date: Thursday, February 6, 2014 3:47 PM To: Richard Rosendall <[email protected]> Subject: Fwd: Updated GLAA answers - discard earlier versions -------------------------------------------------------- Bruce Majors, Libertarian for Mayor PUBLIC HEALTH 1. Will you act to ensure that the District provides transgender-inclusive health insurance to all D.C. Government employees, to include coverage for sex affirmation surgery (also known as sex reassignment surgery)? As Mayor I will seek to increase all options for how District government employees can choose to use their own healthcare dollars, including increasing insurance options and reducing barriers to entry for insurance companies. I would oppose attempts by any level of government to tell D.C. government employees (or anyone else) what treatments or procedures they can pursue. I would not allow the government to define which reconstructive or cosmetic options are approved and which not, but would instead respect consumer sovereignty. I would oppose a precedent of having the D.C. government design a one size fits all health care plan or insurance policy for all D.C. employees. 2. Will you submit budgets that target funds to address health disparities in the LGBT population, including in mental health and substance abuse treatment? I would ensure that funds budgeted for any area do not exclude or discriminate against any population. I would seek to allow each individual more choice in how they use the funds budgeted. Ideally where possible people eligible for these programs would have something like an EBT card or voucher and be able to choose their own care provider.