Genre Theories, Genre Names and Classes Within Music Intermedial Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Treble Culture

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN P A R T I FREQUENCY-RANGE AESTHETICS ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4411 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:53:21:53 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4422 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:54:21:54 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN CHAPTER 2 TREBLE CULTURE WAYNE MARSHALL We’ve all had those times where we’re stuck on the bus with some insuf- ferable little shit blaring out the freshest off erings from Da Urban Classix Colleckshun Volyoom: 53 (or whatevs) on a tinny set of Walkman phone speakers. I don’t really fi nd that kind of music off ensive, I’m just indiff er- ent towards it but every time I hear something like this it just winds me up how shit it sounds. Does audio quality matter to these kids? I mean, isn’t it nice to actually be able to hear all the diff erent parts of the track going on at a decent level of sound quality rather than it sounding like it was recorded in a pair of socks? —A commenter called “cassette” 1 . do the missing data matter when you’re listening on the train? —Jonathan Sterne (2006a:339) At the end of the fi rst decade of the twenty-fi rst century, with the possibilities for high-fi delity recording at a democratized high and “bass culture” more globally present than ever, we face the irony that people are listening to music, with increasing frequency if not ubiquity, primarily through small plastic -

Living and Labouring As a Music Writer

Cultural Studies Review volume 19 number 1 March 2013 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 155–76 Lawson Fletcher and Ramon Lobato 2013 Living and Labouring as a Music Writer LAWSON FLETCHER AND RAMON LOBATO SWINBURNE UNIVERSITY I attended gigs most weeks while studying at university. I was happy to remain a punter until around May, June 2007. A band called Cog played at The Tivoli. After the show, I read a review on FasterLouder.com.au which was poorly-written and factually incorrect—they mentioned a few songs that weren’t played. It pissed me off. I thought: ‘I can do better.’ So I wrote a review of a show I saw that same weekend—Karnivool at The Zoo—and sent it to the Queensland editor of FasterLouder.com.au … He liked it, and published it. I sent the same review to the editor of local street press Rave Magazine, who also liked it, and decided to take me on as an ‘indie’ CD reviewer; later, I started writing live reviews for Rave, too. ‘Dale’, a 23-year old freelance music writer Like most music critics in Australia, Dale is an autodidact. His entry into a writing career started with ad hoc reviews for websites and local music magazines. Over ISSN 1837-8692 time he built up a network of contacts, carefully honed his craft, and is now making a living by writing reviews and interviews for various magazines and websites. The money isn’t good, but it’s enough to live off—and Dale relishes the opportunity to influence how his readers understand and enjoy the culture around them and contribute to a wider conversation about music. -

The Concert Hall As a Medium of Musical Culture: the Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19Th Century

The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century by Darryl Mark Cressman M.A. (Communication), University of Windsor, 2004 B.A (Hons.), University of Windsor, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darryl Mark Cressman 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Darryl Mark Cressman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century Examining Committee: Chair: Martin Laba, Associate Professor Andrew Feenberg Senior Supervisor Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Barry Truax Internal Examiner Professor School of Communication, Simon Fraser Universty Hans-Joachim Braun External Examiner Professor of Modern Social, Economic and Technical History Helmut-Schmidt University, Hamburg Date Defended: September 19, 2012 ii Partial Copyright License iii Abstract Taking the relationship -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

Культура І Мистецтво Великої Британії Culture and Art of Great Britain

НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИХ НАУК УКРАЇНИ ІНСТИТУТ ПЕДАГОГІКИ Т.К. Полонська КУЛЬТУРА І МИСТЕЦТВО ВЕЛИКОЇ БРИТАНІЇ CULTURE AND ART OF GREAT BRITAIN Навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи Київ Видавничий дім «Сам» 2017 УДК 811.111+930.85(410)](076.6) П 19 Рекомендовано до друку вченою радою Інституту педагогіки НАПН України (протокол №11 від 08.12.2016 року) Схвалено для використання у загальноосвітніх навчальних закладах (лист ДНУ «Інститут модернізації змісту освіти». №21.1/12 -Г-233 від 15.06.2017 року) Рецензенти: Олена Ігорівна Локшина – доктор педагогічних наук, професор, завідувачка відділу порівняльної педагогіки Інституту педагогіки НАПН України; Світлана Володимирівна Соколовська – кандидат педагогічних наук, доцент, заступник декана з науково- методичної та навчальної роботи факультету права і міжнародних відносин Київського університету імені Бориса Грінченка; Галина Василівна Степанчук – учителька англійської мови Навчально-виховного комплексу «Нововолинська спеціалізована школа І–ІІІ ступенів №1 – колегіум» Нововолинської міської ради Волинської області. Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії : навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи / Т. К. Полонська. – К. : Видавничий дім «Сам», 2017. – 96 с. ISBN Навчальний посібник є основним засобом оволодіння учнями старшої школи змістом англомовного елективного курсу «Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії». Створення посібника сприятиме подальшому розвиткові у -

A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music with Ellen Allien

Editorial A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music With Ellen Allien Kian McHugh | August 3, 2020 When my Zoom call with Ellen Allien connects, at last, I feel weeks of anticipation turn to uncontrollable excitement. My fingers, sweaty from nerves, and a poorly brewed Starbucks coffee, type out the instructions on how to get her audio configured. Ellen is lounging in her Ibiza flat where she has painted all of the walls completely black so that when the sun shines through her window, the room glows yellow. The first fully formed thought I could pencil down was that her posture seemed to denote a sincere attention to detail and confidence in comfort that most others lack. For the first 2 minutes of the call, we both instinctively laugh, muted, and unaware that our discussion of Techno would soon gravitate toward, and then find unexpected momentum in… a deep consideration of Techno, God, and religion. “Rap is where you rst heard it… If rap is more an American phenomenon, techno is where it all comes together in Europe as producers and musicians engage in a dialogue of dazzling speed.” – Jon Savage (English writer, broadcaster and music journalist). In Hanif Abdurraqib’s 2019 book, Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, he so beautifully praises “the low end” of a track: “The feeling of something familiar that sits so deep in your chest that you have to hum it out … where the bass and the kick drums exist.” His point rings true across all music that is heavily percussion driven. -

Genre Theories and Their Applications in the Historical and Analytical Study of Popular Music: a Commentary on My Publications

University of Huddersfield Repository Fabbri, Franco Genre theories and their applications in the historical and analytical study of popular music: a commentary on my publications Original Citation Fabbri, Franco (2012) Genre theories and their applications in the historical and analytical study of popular music: a commentary on my publications. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/17528/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Genre theories and their applications in the historical and analytical study of popular music: a commentary on my publications By Franco Fabbri University of Huddersfield June 2012 Genre theories and their applications in the historical and analytical study of popular music: a commentary on my publications By Franco Fabbri A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Published Works The University of Huddersfield June 2012 – 2 – Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................... -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ...................................................................................... -

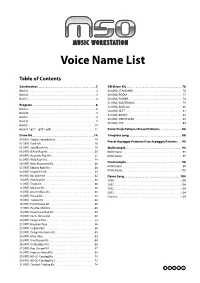

M50 Voice Name List

Voice Name List Table of Contents Combination . .2 GM Drum Kit . 76 Bank A. .2 48 (GM): STANDARD . 76 Bank B. .3 49 (GM): ROOM . 77 Bank C. .4 50 (GM): POWER. 78 51 (GM): ELECTRONIC . 79 Program . .6 52 (GM): ANALOG . 80 Bank A. .6 53 (GM): JAZZ . 81 Bank B. .7 54 (GM): BRUSH . 82 Bank C. .8 55 (GM): ORCHESTRA. 83 Bank D . .9 56 (GM): SFX . 84 Bank E . 10 Bank G / g(1)…g(9) / g(d). 11 Drum Track Patterns/Preset Patterns. 86 Drum Kit . .14 Template song . 88 00 (INT): Studio Standard Kit. 14 Preset Arpeggio Patterns/User Arpeggio Patterns . 90 01 (INT): Funk Kit. 16 02 (INT): Jazz/Brush Kit . 18 Multisample. 94 03 (INT): B.Real Rap Kit . 20 ROM mono . 94 04 (INT): Acoustic Pop Kit. 22 ROM stereo . 97 05 (INT): Wild Rock Kit . 24 Drumsample . 98 06 (INT): New Processed Kit. 26 07 (INT): Electro Rock Kit . 28 ROM mono . 98 08 (INT): Insane FX Kit . 30 ROM stereo . 103 09 (INT): Nu Style Kit . 32 Demo Song. 104 10 (INT): Hip Hop Kit . 34 S000 . 104 11 (INT): Tricki kit. 36 S001 . 104 12 (INT): Mashed Kit. 38 S002 . 104 13 (INT): Drum'n'Bass Kit . 40 S003 . 104 14 (INT): House Kit . 42 Cue List . 104 15 (INT): Trance Kit . 44 16 (INT): Hard House Kit . 46 17 (INT): Psycho-Chill Kit . 48 18 (INT): Down Low Rap Kit. 50 19 (INT): Orch.-Ethnic Kit . 52 20 (INT): Original Perc . 54 21 (INT): Brazilian Perc. 56 22 (INT): Cuban Perc .