Blacks in the Military from Colonial Days to Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

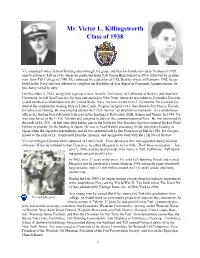

Mr. Victor L. Killingsworth Class of 1938

Mr. Victor L. Killingsworth Class of 1938 Vic attended Conley School Kindergarten through 3rd grade and then his family moved to Ventura in 1929, only to return to Taft in 1936 where he graduated from Taft Union High School in 1938, followed by gradua- tion from Taft College in 1940. He continued his education at CAL Berkley where in February 1942, he en- listed in the Navy and was allowed to complete his Bachelor of Arts degree in Personnel Administration, be- fore being called to duty. On December 3, 1942, along with a group of men from the University of California at Berkley and Stanford University, he left San Francisco by train and arrived in New York, where he was taken to Columbia Universi- ty and enrolled as Midshipmen in the United States Navy, his tour for the next 3 1/2 months. He reported for duty at the amphibious training base at Little Creek, Virginia in April 1943, then went to Fort Pierce, Florida for advanced training. He was ordered aboard the U.S.S. Sumter, an amphibious transport. As a amphibious officer his landing board division took part in the landings at Kwajalein Atoll, Saipan and Tinian. In 1944, Vic was transferred to the U.S.S. Artemis and assigned to duty as the communication officer. He was promoted to the rank of Lt. (JG). At this time after taking part in the battle for Iwo Jima his ship was ordered back to Pearl Harbor to prepare for the landing in Japan. He was in Pearl Harbor preparing for the upcoming landing in Japan when the Japanese surrendered, and he was ordered back to San Francisco in March 1944. -

SIP KIM DS "La Vo2- Jet Gaea-Te-113

YIMYYYM MINYYMM YINYMYYMOYYM MYEMYYM MY.I.YMY MMMIM1 MY. YNIMMYMM MYMMMY Y2 IYMMMYM11.= IIMYMMIMY ..my ymm MEMO MIYM myyy IYMOMM my. mmy YMM mymyy myMY myyy myymyymmmmyyy ymmyymyImmma YM ymyyyMYMMUMNY MYMYYM YMIMIII.MMY MYY11IYMMI .1my «MY Y101 MIYIBIYMY MY By YY11 oyM y.yyy MY MIYI My MY MMM MIMMI MO YIMM BaMMW MMI MMY WYM MY IY11 YMYYMIM MYM11 YMYMYM NIIYI MY. MYYRYYM MYiMM YYMOMM YOYMMIM MYB3 ffln YM YMYYMBYYMMYM ,;m MYYMY MYMMY« YMMYY Volume 18 FEBRUARY/MARCH 1988 Number 2 SIP KIM DS "La Vo2- Jet gaea-Te-113.. ECUaclor." Opportunities Available! See 'Keynotes". page 46 IN THE FEBRUARY/MARCH SPEEDX... 2 DX Montage Janusz 27 Africa Ouaglieri 7 Program Panorama Seymour 33 Asia/Oceania Thunberg 9 Station Skeds Bowden 39 Utility Scene Knapp & Sable 45SPEEDXSpotlights Trautschold 12 North America Caribbean Kephal-t le Latin amerite, , :::,,,,, ,Muff alter 40 Keyntitee 20 Europe Sampson 47 Subscription Service Form 233SSR Berri THE DX MAGAZINE FOR ACTIVE SWILs !!1"/!l ® n a u e vw.0 TV ;. Ed Janusz Box 149 Bricktown, NJ 08723 THE OFFICIAL RADIO NOOZE COLUMN OF THE 1988 OLYMPICS.... FEBRUARY, 1988 Hi. Thanks to all of you who have written to this column; the turnout this month has been super. And what is your reward, gentle SPEEDX'ers? Why, more work, that's what! SPEEDX REDUX: OR, THE RETURN OF THE POLL Remember the SPEEDX Popularity Poll which ran in these pages last July? We're doing it again...with a few new questions. 1) What are your five favorite INTERNATIONAL short wave stations? 2) What are your three favorite TROPICAL -BAND stations? 3) Which station provides the best WORLD NEWS coverage? 4) Ditto for REGIONAL NEWS coverage. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

![The American Legion [Volume 135, No. 4 (October 1993)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2224/the-american-legion-volume-135-no-4-october-1993-3532224.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 135, No. 4 (October 1993)]

WHAT OUR CHILDREN SHOULD KNOW ALP MAIL ORDER DON'T PAY $lSOi Get all the features, all the warmth, all the protection of expensive costs, fc jW^ now only 39.95 from Haband. LOOK: SB • Rugged waterproof 65% polyester, 35% cotton poplin shell. • Hefty insulated storm collar • Detachable insulated snorkel hood with drawstring. • Warm cozy 7 oz. polyester fiberfill body insulation. • Big, fumble-free zipper and snap storm flap. • 2 secure flap pockets at chest. • Generous top and side entry cargo pockets. • 2 secure inside pockets. Good long seat-warming length. •Drawstring waist. • Warm acrylic woven plaid lining. *Easy-on nylon lined sleeves and bottom panel. And of course, 100% MACHINE WASHAND DRY! heck and compare with the finest coats anywhere. Try on for fit. Feel the enveloping warmth! $150? NO WAY! Just 39.95 from Haband and you'll LOVE III SIZES: S(34-36) M(38-40) L(42-44) XL(46-48) *ADD $6 EACH 2XL(50-52) 3XL(54-56) 4XL(58-60) WHAT HOW 7BF-3F3 SIZE? MANY? A NAVY B WINE C FOREST D GREY Haband One Hundred Fairview Avenue, Prospect Park, NJ 07530 Send coats. I enclose $ purchase price plus $4.50 postage and handling. Check Enclosed Discover Card DVisa DMC exp. / Apt. #_ Zip_ 100 FAIRVIEW AVE. 100% Satisfaction Guaranteed or Full Refund of Purchase Price at Any Time! HABAND PROSPECT PARK, NJ 07530 fr£> The Magazine for a Strong America Vol. 135, No. 4 October 1993 : A R T I C L STUDY LINKS AGENT ORANGE WITH MORE DISEASES Vietnam veterans may be able to receive compensationfor additional ailments. -

![The American Legion [Volume 142, No. 3 (March 1997)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6999/the-american-legion-volume-142-no-3-march-1997-3606999.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 142, No. 3 (March 1997)]

Le Sabre Peac IBl 1 TO LeSabre Peace of mind. $500 Member Benefit January 15 through March 31, 1997 LeSabre, LeSabre Living Space Safe Priorities Comfort and quality are synonymous with LeSabre. From the carefully contoured seats to the refined quiet ride, Buick continues to build a strong safety reputation with a wide the confidence that Buick array of standard safety features such as dual airbags and anti- owners experience is the lock brakes. The safety and security of you and your family are most important quality top priorities with LeSabre. There has never been a better of all time to visit your local Buick dealer Take advantage of Buick savings as a member of the So drive into your local American Legion family From Buick dealer today with the January 15 through March 31, attached American Legion 1997, you can save $500 in $500 Member Benefit addition to a LeSabre national Certificate from LeSabre. cash-off incentive on the When you purchase or lease purchase or lease of a new your 1997 LeSabre, you'll also and unused 1997 LeSabre. be contributing to a very The optional leather interior features a wrap around See your local Buick dealer worthy cause. Buick will instrument panel. for details. donate $100 to your local Post or Auxiliary for the support of American Legion Baseball. LeSabre offers dual air bags as a standard feature. Always wear When filling out your member certificate, remember to include your safety belts even with your local Post # or Auxiliary Unit #. LeSabre, The American Another powerful reason for LeSabre 's best seller status, the 3800 Series II V6 engine's 205 horsepower Legion's Choice A full-size car with its powerful 3800 Series 11 SFI V6 engine provides effortless cruising for a family of six. -

08 Mii Mmmie M.E0 MEDIUM MMEMIMIFIE.MO IIMEI Mma

0PL MMMIIMM fiDIMINEL MMMMI IMUMMMM MueMlaMeM MME 11191MIMMMEMI MED MEM MOIMMIEMMILM 0 MOM mUl IM MMUM 01 MMIV0 KUMAR IIIIMM diM OMM MMEM MD= MIMM MOB IML MIMMLIMMEPA BBB MMI K® Wm MEMEMMMME MEMMMEL iMMPE MOM MMMEMEMOMM era MEM MM. UMMINMILMmm.M MUM MMIMMIIIM 08 Mii MmmiE M.E0 MEDIUM MMEMIMIFIE.MO IIMEI MMa .. MEMMM. RIMMM MEM III .1 MEME MM. MEMEMIIMMEM MIll MO IMM MMIMMILM.MME Imlm MEM Mom. MM. ISMOille MIlliIIMM 0 man EL EMI MINIMMEMMULEM MEM OMIEMMIMM RIMME KAMM MEMEIEMMM AVEM0 EMMM DANTE B. FASCELL, FLum Csmo. a=1=7"!'-'" STEPHEN J. SOLARS. NEW .R1 WILLIAM S. BROOMFIELD, Elmo. DON FIONKEII. W.RoLoToLL One hundredth Congress BENJAM A_ GILMAN, Nov You GERRY E. SMASS. DIRSammerrs ROBERT J. LAGOMARSINO. CALIFORNIA DAN MICA. PAR. JIM LEACH, loom HOWARD WOLPE. AILERKALL OLBY ROTH. M. GEO. W CROCKETT. JR., McHmx &was of the United g5tates YMPIA SAME Ma SAM GEJOENSON. CONNKTICur HENRY J. HYDE. ILLIM MERVYN M. OYMALLY, Moon. GERALD B.H. SOLOMON, N. To. TOM LANTOS, CALIFORRP DOUG °MUTER. HEBRAIIII. PET. H. KOMMEIL. PPIR.L.Ro Committee on foreign 21fTairs ROBERT K. DORNAN, CALIFORNIA ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, NEW JEuev CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH. Mr MEP LAWRENCE J SMITH. FLORIDA CONNIE MACK. FLOM HOWARD L BERMAN. Moon. MICHAEL DENIM. 0100 MEL LEVINE CLIF.. Moose of llttprestntatho DAN BURTON, INDIANA JAN EDWARD F FEIGHAN. OHLO EYERS. 10... TED WEISS. NM YORK JOHN MILLER. WASNIRDTON GARY L ACKERMAN. Mew YORK Washington, 3DiZ2015 DONALD E LUKENS. MO MORRIS K UDALL. Am. BEN BLAZ GUAM CHESTER G. ATKINS. LARs...erTs ST.. K. BERRY JAM. M.LURE CLARKE. -

Summary of Gl Projects/Mpers .Overseas Done by Region; U.S. Done by Service) West Germany: Fight Back (Heidelberg) Remains One O

Summary of Gl projects/mpers .Overseas done by region; U.S. done by service) West Germany: FighT bAck (Heidelberg) remains one of the most regularly-prodaced papers, four issues in 1973. While Forward (Berlin) has been less regular (one issue in March) both it and FighT bAck seem strong, as GIs in 'Vest Germany face an unbelievably repressive "anti-drug"movement" by the 7th Army. The arrival of the Lawyers Military Defense Committee (two civilian lawyers, Robert Rivkin and Howard DeNike) has been a real plus for their work. LMDC is going to seek to enjoin the Army from stopping its war on EM. The paper PTA with Pride s (Weisbaden-Mainz) seems to have been more hard hit by the Army's January rix transfers of political activists than FighT bAck. GIs connected with the paper are still there, but no paper in a while. Asia : Semper FI is still coming out every payday (twice a month) like clockwork. The ranks of the Iwakuni WAW chapèer which produced it have been depleted by Marine repression, but seems to be building up again. A very long report from them was in the March 'Bulletin; they seem solid. Omega Press fdks in Okinawa seem active, though the paper hasn't been out in a while. They're involved in a defense campaign for the Sumter Three, 3 black marines apparently being framed for their anti-racist activity on the USS Sumter. We've heard nothing from the other h PCS orojects in Asia for quite a while, though they're all still there, near Yokota AFB, Yokosuka Naval Base, Misawa AFB, and in Kin (also on Okinawa)—all in Japan. -

SUMMER 2014 from the Galley

General Fulton/Omar Bradley Honoring Army KIAs on the Benewah Last 5 Star General Dong Tam 1967 A PUBLICATION OF VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 THE MOBILE RIVERINE FORCE ASSOCIATION SUMMER 2014 From the Galley and okay and having some nice weatherHope thisafter finds all the everyone bad weather well we have had the last few months; it was a wicked winter that went into the spring. Not much going on—the asso- ciation is up and running on all cylinders with no problems. Lively Tom Some of you have asked how Al Moore you can get on the base at Coro- nado to see the CCB and other boats, and the memorial wall as well. Member Tom Fire Direction Control Mason explains below. by Tom Lively 3rd/34th Arty on call at all times with two guys on map- Update on the Unit ([email protected]) ping charts. If we got a call from a unit that needed some help, I would take the Memorial and Albert—Of all my experiences and now basic info including grid location and Boat Visitation stories about the RVN, this is the one that what contact had been established (am- Requirements is most difficult for me and causes me the As we work most problem even today. I guess I just etc.). My job was to get things started and daily and weekly need to get it out there to purge my mind offer them immediate assistance. The on the Memo- or something like that. bush . taking fire from bunkers . sniper, two guys on the charts would identify rial, we are always Like I said, I was one of the RTOs for complimented their grid location and verify the same on both charts and then plot distance, on its appear- some miles south of Ben Tre. -

Deck Log of the USS LCI(L) 713 Official Newsletter of the Amphibious Forces Memorial Museum

Deck Log of the USS LCI(L) 713 Official Newsletter of the Amphibious Forces Memorial Museum The AFMM Hosts the 2017 LCI National Reunion Summer 2017 “Deck Log of the USS LCI (L) 713” Summer 2017 Official publication of the Amphibious Forces Memorial Museum (AFMM) an Oregon based non-profit charitable organization. Membership is open to anyone interested in supporting our mission. For online memberships or donations, check our website or submit the attached form. Thanks to our volunteers: J Wandres, Rich Lovell, Gordon Smith and Mark Stevens. for their contributions. Contact [email protected] Website: www.lci713.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/lci713 ________________________________________________________________________ AFMM and LCI National Alliance The AFMM is now officially in an alliance with the LCI National Association. We will be cooperating on our areas of common interest, such as preservation of historical documentation and artifacts such as our favorite, the LCI-713. The AFMM will help in hosting LCI reunions. Interested in the LCI National Association? Website: www.usslci.com Help us Launch the LCI-713! (Cut Here and return) ___________________________________________________________________________ Amphibious Forces Memorial Museum Note: If you don’t want to use the form, it’s Rick Holmes, President ok.. However, please keep us up to date on PO Box 17220 your contact info for our mailings. Thanks! Portland, OR 97217 Dear Rick: Here is my contribution of $______________ to help get the LCI-713 underway. Name:___________________________________________________________ -

The Struggle for Port Hudson (Civil War, Louisiana, Military). Lawrence Lee Hewitt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1984 "They Fought Splendidly!": the Struggle for Port Hudson (Civil War, Louisiana, Military). Lawrence Lee Hewitt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Hewitt, Lawrence Lee, ""They ouF ght Splendidly!": the Struggle for Port Hudson (Civil War, Louisiana, Military)." (1984). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4017. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4017 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

![The American Legion [Volume 137, No. 6 (December 1994)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7286/the-american-legion-volume-137-no-6-december-1994-9337286.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 137, No. 6 (December 1994)]

1 VWERE' 29.95/ HJiBJiNO'S 1 imported Now with Thinsulate THERMAL INSULATIION WARMER THAN EVER BEFORE! We added Thinsulate™ thermal insulation throughout the whole foot to maximize warmth for your winter protection and comfort. Try this and all these other features on for size: • Water-repellent, flexible, man-made uppers wipe clean — never need polishing. • Decorative strap with gold-tone buckle around top adds a nice fashion touch. • Warm, acrylic fleece lining, top to toe. • Thick, foam-padded cushioned insoles. • No-slip, MEDIUM bouncy traction grip sole. • Full side zipper for easy WIDE SIZES! on, easy off. All this, and a terrific price to boot! 1 Now you don't have to sacrifice warmth for style! These boots 2 for 49.50 »° 24"* Winter Boot 3 for 74.00 have it all - warm fleecy lining and handsome good looks Haband One Hundred Fairview Ave., Prospect Park, NJ 07530 with fancy stitched detail, to wear with everything from suits D and EEE* Widths 7BY-48P What D or How to jeans! Here's your chance to stock up! Use the easy order Size? EEE? Many? (*add $2 per pair for EEE): C TAUPE form and send today! 7 7% 8 872 9 9/2 10 D BROWN 10/2 11 12 13 E BLACK Send me pairs of boots. I enclose $ purchase price, plus $3.50 toward postage and insurance. Check enclosed Discover Card Visa MasterCard Card #____ Exp.: __/__ Mr. Mrs. Ms. Mail Address Apt. # 100 Fairvicw Avenue City Thinsulate is a & State Zip 100% Satisfaction Guaranteed or Full Refund of Purchase Price at Any Time! Prospect Park, NJ 07530 trademark of 3M. -

The Starfleet Registry

THE STARFLEET REGISTRY RESEARCHED AND COMPILED BY JOHN W. BULLERWELL Introduction What you hold is perhaps the most comprehensive listing of the NCC- and NX- Federation Starfleet registration numbers ever created. Unfortunately, as comprehensive as it is, it is also confusing, error filled and riddled with mysteries. These numbers are from the entirety of fandom and canon. If you’re looking for a work of completely canon numbers and nothing else, this is not the document for you. Because the majority of these numbers come from fandom, there are a lot of discrepancies, and a lot of replication. There are numerous considerations I needed to make in compiling the list. For instance, I worked under the assumption that a ship with a lettered suffix (for example NCC-1234-C) is carrying a registry ‘tradition’, like the Enterprise. Therefore, if fandom listed a NCC-XXX-A U.S.S. No Name, I assumed the was a NCC-XXX (no suffix) No Name as well. While this is indeed very unlikely, I included them for the sake of completeness, as the original originator likely intended. Also, spellings in this document are intentional. If a ships name was Merrimac, I did not change it to Merrimack, or vice-versa. Again, it is assumed that the originator of the ship’s name/number intended their spelling to be correct. Some vessels had the same names and numbers, but were listed under two different class names. An example of this would be the Orka-class and the Clarke-class. Both classes had the same ships and numbers.