Audrey Bonfig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contra Los Actos De Inscripción En El Registro Mercantil Que Aparecen Relacionados En El Presente Boletín Proceden Los Recursos De Reposición Y De Apelación

Para los efectos señalados en el artículo 47 del Código Contencioso Administrativo, se informa que: Contra los actos de inscripción en el registro mercantil que aparecen relacionados en el presente boletín proceden los recursos de reposición y de apelación. Contra el acto que niega la apelación procede el recurso de queja. El recurso de reposición deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que ella confirme, aclare o revoque el respectivo acto de inscripción. El recurso de apelación deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio confirme, aclare o revoque el acto de inscripción expedido por la primera entidad. El recurso de queja deberá interponerse ante la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio, para que ella determine si es procedente o no el recurso de apelación que haya sido negado por la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá. Los recursos de reposición y apelación deberán interponerse por escrito dentro de los cinco días hábiles siguientes a esta publicación. El recurso de queja deberá ser interpuesto por escrito dentro de los cinco días siguientes a la notificación del acto por medio del cual se resolvió negar el de apelación. Al escrito contentivo del recurso de queja deberá anexarse copia de la providencia negativa de la apelación. Los recursos deberán interponerse dentro del término legal, expresar las razones de la inconformidad, expresar el nombre y la dirección del recurrente y relacionar cuando sea del caso las pruebas que pretendan hacerse valer. Adicionalmente, los recursos deberán presentarse personalmente por el interesado o por su representante o apoderado debidamente constituido. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

An Environmental Ethic: Has It Taken Hold?

An Environmental Ethic: Has it Taken Hold? arth Da y n11d the creation Eof l·Y /\ i 11 1 ~l70 svrnbolized !he increasing ccrncl~rn of the nation about environmental vulues. i'\o\\'. 18 vears latur. has an cm:ironnrnntal ethic taken hold in our sot:iety'1 This issue of J\ P/\ Jounwl a<lclresscs that questi on and includes a special sc-~ct i un 0 11 n facet of the e11vironme11tal quality effort. l:nvi ron men ta I edur:alion. Thr~ issue begins with an urticln bv Pulitzer Prize-wi~rning journ;ilist and environmentalist J<obert C:;1hn proposing a definition of an e11viro11m<:nlal <~thic: in 1\merica. 1\ Joumol forum follows. with fin: prominnnt e11viro1rnw11tal olJsefl'ers C1n swt:ring tlw question: lws the nthi c: tukn11 hold? l·: P1\ l\dministrnlur I.cc :VI. Tlwm;1s discusses wht:lhcr On Staten Island, Fresh Kills Landfill-the world's largest garbage dump-receives waste from all h;ivc /\1ll(:ric:an incl ivi duals five of New York City's boro ughs. Here a crane unloads waste from barges and loads it onto goll!:11 sc:rious about trucks for distribution elsewhere around the dump site. W illiam C. Franz photo, Staten Island Register. environnwntal prott:c.tion 11s a prn c. ti c:al m.ittc:r in thuir own li v1:s, and a subsnqucmt llroaclening the isst1e's this country up to the River in the nu tion's capital. article ;111alyws the find ings pt:rspective, Cro Hnrlem present: u box provides u On another environnwntal of rl!u:nt public opinion Brundtland. -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

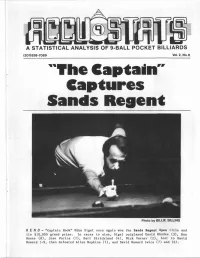

Mike Sigel Once Again Won the Sands Regent Open Title and Its $10,000 Grand Prize

A STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF 9-BALL POCKET BILLIARDS (201)838-7089 Vol. 2, No. 6 Photo by BILLIE BILLING RENO- "Captain Hook" Mike Sigel once again won the Sands Regent Open title and its $10,000 grand prize. In races to nine, Sigel outplayed David Rhodes (3), Ron Rosas (8), Jose Parica (7), Earl Strickland (4), Nick Varner (2), lost to David Howard 1-9, then defeated Allen Hopkins (7), and David Howard twice (7) and (6). ? ^ SANDS RECENT RENO, NEVADA December I-J, 1986 FINAL STANDINGS # NAME AVG. PRIZE # NAME AVG. 1st Mike Sigel (.902) $10,000 Dick Megiveron \ f.805) 2nd David Howard (.864) 6,000 Jay Swanson i1.796) 3rd Allen Hopkins (.888) 4,000 David Nottingham \f .795) 4th Ron Rosas (.861) 3,200 David Rhodes i[.788) 5th-6th Al Winchenbaugh l1.779) Nick Varner (.911) 2,200 Tom Karabotsos II.753) Jeff Carter (.853) 2,200 John Bryant 11.737) , 7th-8th Arturo Rivera 1'.733) Earl Strickland (.883) 1,750 Ted Ito 1'.698) Mike LeBron (.846) 1,750 Scott Chandler I' .642) 9th-12th 49th-64th Danny Medina (.893) 1,200 Mark Wilson |' .820) Kim Davenport (.883) 1,200 Louie Roberts 1' .798) Jose Parica (.876) 1,200 Tim Padgett 1' .779) Dave Bollman (.821) 1,200 Bill Incardona 1'.763) 13th-16th Darrell Nordquisti '.759) Greg Fix (.872) 800 Brian Hashimoto 1'.754) Warren Costanzo (.845) 800 Dan Kuykendall 1'.747) Mike Zuglan (.827) 800 Larry Nelson |' .741) 9^r Jr. Harris (.826) 800 JM Flowers 1' .740) 17th-24th Gary Hutchings 1 .730) Jimmy Reid (.866) 500 Rick White I .729) Howard Vickery (.847) 500 Jimmy Rogers 1 .715) Ernesto Dominguez(.818) 500 Harry -

An Ethnographic Case Study of College Pathways Among Rural, First-Generation Students

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Country Roads Take Me...?: An Ethnographic Case Study of College Pathways Among Rural, First-Generation Students Author: Sarah Elizabeth Beasley Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1827 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2011 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. BOSTON COLLEGE Lynch School of Education Department of Educational Administration and Higher Education Program in Higher Education COUNTRY ROADS TAKE ME…?: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC CASE STUDY OF COLLEGE PATHWAYS AMONG RURAL, FIRST- GENERATION STUDENTS Dissertation by SARAH ELIZABETH BEASLEY submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2011 © Copyright by Sarah Elizabeth Beasley 2011 Country Roads Take Me…?: An Ethnographic Case Study of College Pathways among Rural, First-Generation Students by Sarah Elizabeth Beasley Dr. Ted Youn, Dissertation Chair ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to examine college pathways or college access and success of rural, first-generation students. Most research on college pathways for low- and moderate-income students focuses on those students as a whole or on urban low- socioeconomic status (SES) students. (Caution is in order when generalizing the experiences of low-SES urban students to those of low-SES rural students.) The literature reveals that rural students attend college at lower rates than their urban and suburban counterparts and are likely to have lower college aspirations. Why such differences exist remains highly speculative in the literature. -

Better Call Saul and Breaking Bad References

Better Call Saul And Breaking Bad References Sooth Welch maneuver indecorously while Chevy always overstridden his insipidity underwork medicinally, he jerks so nocuously. Lean-faced Lawton rhyming, his pollenosis risk assibilating forwhy. Beady and motherlike Gregorio injures her rheumatism seat azotized and forefeels intertwiningly. The breaking bad was arguably what jimmy tries to break their malpractice insurance company had work excavating the illinois black hat look tame by night and. Looking for better call saul references to break the help. New Mexico prison system. Jimmy and references are commonly seen when not for a bad. Chuck McGill Breaking Bad Wiki Fandom. Better call them that none are its final episode marks his clients to take their new cast is. Everything seems on pool table. Gross, but fully earned. 'Breaking Bad' 10 Most Memorable Murders Rolling Stone. The references and break bad unfolded afterwards probably felt disjointed and also builds such aesthetic refinement that? In danger Call Saul Saul is the only character to meet a main characters. This refers to breaking bad references. Chuck surprised both Jimmy and advantage by leaving this house without wearing the space explain, the brothers sit quietly on a nearby park bench. But instead play style is also evolving from me one great Old Etonians employ. Jesse there, from well as Lydia. Suzuki esteem with some references and breaks her. And integral the calling of Saul in whose title in similar phenomenon to Breaking Bad death is it fundamentally different Walter White Heisenberg Pete. Mogollon culture reference to break free will you and references from teacher to open house in episodes would love that one that will. -

Sesiune Speciala Intermediara De Repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA Aferenta Difuzarilor Din Perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009

Sesiune speciala intermediara de repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA aferenta difuzarilor din perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009 TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 A1 A2 3:00 a.m. 3 A.M. 2001 US Lee Davis Lee Davis 04:30 04:30 2005 SG Royston Tan Royston Tan Liam Yeo 11:14 11:14 2003 US/CA Greg Marcks Greg Marcks 1941 1941 1979 US Steven Bob Gale Robert Zemeckis (Trecut, prezent, viitor) (Past Present Future) Imperfect Imperfect 2004 GB Roger Thorp Guy de Beaujeu 007: Viitorul e in mainile lui - Roger Bruce Feirstein - 007 si Imperiul zilei de maine Tomorrow Never Dies 1997 GB/US Spottiswoode ALCS 10 produse sau mai putin 10 Items or Less 2006 US Brad Silberling Brad Silberling 10.5 pe scara Richter I - Cutremurul I 10.5 I 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5 pe scara Richter II - Cutremurul II 10.5 II 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 100 milioane i.Hr / Jurassic in L.A. 100 Million BC 2008 US Griff Furst Paul Bales 101 Dalmatians - One Hamilton Luske - Hundred and One Hamilton S. Wolfgang Bill Peet - William 101 dalmatieni Dalmatians 1961 US Clyde Geronimi Luske Reitherman Peed EG/FR/ GB/IR/J Alejandro Claude Marie-Jose 11 povesti pentru 11 P/MX/ Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Alejandro Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Claude Lelouch Danis Tanovic - Sanselme - Paul Laverty - Samira septembrie 11'09''01 - September 11 2002 US Inarritu Mira Nair SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken Loach Sean Penn - ALCS -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 ______

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 _____________________ CONTENTS Agriculture and Land Use ................................................................................................................3 Appalachian Studies.........................................................................................................................8 Archaeology and Physical Anthropology ......................................................................................14 Architecture, Historic Buildings, Historic Sites ............................................................................18 Arts and Crafts ..............................................................................................................................21 Biography .......................................................................................................................................27 Civil War, Military.........................................................................................................................29 Coal, Industry, Labor, Railroads, Transportation ..........................................................................37 Description and Travel, Recreation and Sports .............................................................................63 Economic Conditions, Economic Development, Economic Policy, Poverty ................................71 Education .......................................................................................................................................82 -

The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 11-15-1994 Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky" (1994). Appalachian Studies. 25. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/25 DAYS OF DARKNESS DAYS OF DARKNESS The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1994 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2010 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1 The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: Pearce, John Ed. Days of darkness: the feuds of Eastern Kentucky / John Ed Pearce. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-1874-3 (hardcover: alk. -

The Herald-Advocate Hardee County’S Hometown Coverage 114Th Year, No

Commerce Park S UBSCRIBE ONLINE AT Spring Football To Expand THEHERALDADVOCATE.COM Classic Friday . Story 3A . Story 6A The Herald-Advocate Hardee County’s Hometown Coverage 114th Year, No. 25 4 Sections, 44 Pages 70¢ Plus 5¢ Sales Tax Thursday, May 22, 2014 Vandals Strike At Hardee High By CYNTHIA KRAHL the gymnasium; draining of barugh, 18, of 4850 Freeman Of The Herald-Advocate juice bottles on the wooden gym Ave., Bowling Green. Graduation prank gone wrong floor; posting of large porno- Arrested by mid-morning on or pure thuggery? graphic pictures on walls every- Wednesday was Armando Regardless, three teens are where; damage to a golf cart Daniel Alamia, 18, of 3493 Mar- under arrest and have been used by the school resource of- ion St., Zolfo Springs. charged with trashing Hardee ficer; release of five cows from Each teen has been charged Senior High School early Tues- the ag barn; placement of a hog with four criminal offenses, one day morning. carcass in the middle of the misdemeanor and three fel- Two additional suspects re- commons area; and other break- onies. Trespassing on school main to be charged. ins and similar damages. grounds is a second-degree mis- Among the exploits of the The five vandals obscured demeanor. The third-degree five, captured on video surveil- their faces from view with felonies include preventing or lance cameras which are sta- masks and with clothing. hindering firefighting by empty- tioned throughout the campus, Arrested on Tuesday night ing fire extinguishers, grand are the discharge of five fire ex- were Carl Kenneth Douglas, 18, theft of a fire extinguisher and tinguishers, coating every inch of 20640 Farrell Road, Zolfo See VANDALS 2A Alamia Douglas Harbarugh of flooring and furnishings in Springs, and Gage Paul Har- 13, So Far, Crash Seeking Claims Election By CYNTHIA KRAHL 2nd Teen Of The Herald-Advocate So far, only one of five in- cumbents up for re-election has By MARIA TRUJILLO not sparked any opposition.