The Big Sandy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topography Along the Virginia-Kentucky Border

Preface: Topography along the Virginia-Kentucky border. It took a long time for the Appalachian Mountain range to attain its present appearance, but no one was counting. Outcrops found at the base of Pine Mountain are Devonian rock, dating back 400 million years. But the rocks picked off the ground around Lexington, Kentucky, are even older; this limestone is from the Cambrian period, about 600 million years old. It is the same type and age rock found near the bottom of the Grand Canyon in Colorado. Of course, a mountain range is not created in a year or two. It took them about 400 years to obtain their character, and the Appalachian range has a lot of character. Geologists tell us this range extends from Alabama into Canada, and separates the plains of the eastern seaboard from the low-lying valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Some subdivide the Appalachians into the Piedmont Province, the Blue Ridge, the Valley and Ridge area, and the Appalachian plateau. We also learn that during the Paleozoic era, the site of this mountain range was nothing more than a shallow sea; but during this time, as sediments built up, and the bottom of the sea sank. The hinge line between the area sinking, and the area being uplifted seems to have shifted gradually westward. At the end of the Paleozoric era, the earth movement are said to have reversed, at which time the horizontal layers of the rock were uplifted and folded, and for the next 200 million years the land was eroded, which provided material to cover the surrounding areas, including the coastal plain. -

Conservation and Management Plan for the Native Walleye of Kentucky

Conservation and Management Plan for the Native Walleye of Kentucky Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Fisheries Division December 2014 Conservation and Management Plan for the Native Walleye of Kentucky Prepared by: David P. Dreves Fisheries Program Coordinator and the Native Walleye Management Committee of the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Fisheries Division 1 Sportsman’s Lane Frankfort, KY 40601 ii Native Walleye Management Committee Members (Listed in Alphabetical Order) David Baker Jay Herrala Fisheries Biologist II Fisheries Program Coordinator KDFWR KDFWR 1 Sportsman’s Ln. 1 Sportsman’s Ln. Frankfort, KY 40601 Frankfort, KY 40601 Eric Cummins Rod Middleton Fisheries Program Coordinator Fish Hatchery Manager KDFWR, Southwestern District Office KDFWR, Minor Clark Fish Hatchery 970 Bennett Ln. 120 Fish Hatchery Rd. Bowling Green, KY 42104 Morehead, KY 40351 David P. Dreves Jeff Ross Fisheries Program Coordinator Assistant Director of Fisheries KDFWR KDFWR 1 Sportsman’s Ln. 1 Sportsman’s Ln. Frankfort, KY 40601 Frankfort, KY 40601 Kevin Frey John Williams Fisheries Program Coordinator Fisheries Program Coordinator KDFWR, Eastern District Office KDFWR, Southeastern District Office 2744 Lake Rd. 135 Realty Lane Prestonsburg, KY 41653 Somerset, KY 42501 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................................................................................................1 History .............................................................................................................................................1 -

Water Resources of the Prestonsburg Quadrangle Kentucky

Geology and Ground- Water Resources of the Prestonsburg Quadrangle Kentucky By WILLIAM E. PRICE, Jr. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1359 Prepared in cooperation with the Agricultural and Industrial Development Board of Kentucky UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.00 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................-...-................................................-....-......-.......... - J Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 1 Scope and purpose of investigation,................................................................................. 1 Well-numbering system....................................................................................................... 3 Methods of study................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................ 5 Geography................................................................................................................................. 5 Location and extent of area............................................................................................ -

Floyd County Times

.. :;.... I -1'-f-fC/')L/ ' CDURTIN ' CHAIR ' FEATURE OF OLD HOUSE THAT NEVER M'.)VED, WAS IN 4 CDUNTIES by Remy P. Scalf (Reprinted from the Floyd County Times, January 14, 1954) In an old house, near the mouth of Breedings Creek in Knott County, live the five Johnsons--three brothers and two sisters --Patrick, John D. , Sidney, Elizabeth, and Allie. Four are unmarried. Patrick, the oldest, is 83. Portraits of their ancestors--Simeon Johnson, lawyer, teacher, and scholar; Fieldon Johnson, lawyer, landowner, and Knott ' s first County Attorney; and Fielding' s wife Sarah (nee Iot son)--look down upon them from the house ' s interior walls. Visitors to the Johnson hane are shown the family ' s most prized possessions and told sanething of their early history. Among the famil y ' s heirloans are their corded, hand-turned fourposter beds that were brought to the house by Sarah Johnson. 'Ihese came fran her first home, the Mansion House, in Wise, Virginia, after the death of her father, Jackie Iotson, Wise County ' s first sheriff. (The Mansion House was better knCMn as the Iotson Hotel, one of southwest Virginia' s famous hostelries. ) At least two of the beds she brought with her have names: one is called the Apple Bed for an apple is carved on the end of each post; Another is the Acorn Bed for the acorns carved on its posts. 'Ihe bed ' s coverlets were also brought fran Virginia along with tableware and sane pitchers lacquered in gold that came from her mother Lucinda ' s Matney family. Visitors are also shown the wedding pl ate, a large platter fran which each Johnson bride or groan ate his or her first dinner. -

Utilization of Detonation Cord to Pre-Split Pennsylvanian Aged Sandstone and Shale, Grundy, Virginia

Utilization of Detonation Cord to Pre-split Pennsylvanian Aged Sandstone and Shale, Grundy, Virginia Steven S. Spagna, L.G., Project Geologist U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Huntington District Figure 1. Upstream end of the Grundy Redevelopment Site Project Summary During Summer 2001, the U.S Army Corps of Engineers awarded a contract to the construction firm of Bush and Burchett of Allen, Kentucky, for the purpose of developing a 13 acre redevelopment site by removing approximately 2.5 million cubic yards of rock (fig. 1). The Redevelopment Site will be the future home for a large portion of the City of Grundy, Virginia. Additional work items include the construction and relocation of 3,000 feet of the Norfolk Southern railroad bed, the placement of 95,000 cubic yards of fill and the placement of 16,000 cubic yards of stone slope protection along the Levisa Fork River. Bush and Burchett received a notice to proceed with construction in July 2001. Currently, the contract is near completion. Current activities include: hauling of material from the Redevelopment Site to the disposal area; placing fill material on the Redevelopment Site, and placing Stone Slope Protection (SSP) along the Levisa Fork river. Approximately one year into the construction highly weathered rock, degraded to near soil-like condition, was encountered in the upstream portion of the excavation. Over one-third of the original cutslope was adjusted and the blasting specifications had to be amended to provide solutions for the material that was encountered in this area. Grundy, Virginia Figure 2. Project Location Map Authorization of Project Located along the banks of the Levisa Fork River, below the 100-year flood elevation, the town of Grundy has been plagued with flooding for years. -

Ickinstn:Y, Justus, Soldier, B. in New York About 1821. He Was Gra.Dua.Ted at the U

~IcKINSTn:Y, Justus, soldier, b. in New York about 1821. He was gra.dua.ted at the U. S. mili tary academy in 1888 and assigned to the 2d in fantry. He became 1st li eutenant, 18 April, 1841, and assistant quartermaster with the rank of cap tain on 3 March, 1847, and led a com pany of vol unteers at Contreras and Churubusco, where he was brevetted major for gallantry on 20 Aug., 1847. He participa.ted in the battle of Chapulte pec, and on 12 Jan., 1848, became captain, which post he vacated and served on quartermaster duty with the commissioners that were running the boundary-lines between the United States lind Mexico in 1849- '50, and in Califol'l1ia in 1850-'5. He became quartermaster with the ra.nk of major on 3 Aug., 1861, fl.nd was stationed at St. Louis fl. ud fl.ttac hed to the staff of Gen. John C. Fremont. He combined the duties of provost-marshal wit.h those of qUfl.rteJ'lnaster of the Depaltment of the West, on 2 Sf'pt., 1861, was appointed Lrigadier genoml of volunteers, and commanded It division on Gen. Fremont's march to Springfield. lIe was a.ccused of dishonesty in his transactions as qua.r termaster, and was arrested on 11 Nov., 1861, by Gen. Hunter, the successor of Gen. Fremont, and ordered to St. Louis, Mo., where he was closely confin ed in the arsena.1. The rigor of his impris onment was mitigated on 28 Feb., 1862, fl.nd in May he was released 0n parol e, but required to re main in St. -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

Indian Raids and Massacres of Southwest Virginia

Indian Raids and Massacres of Southwest Virginia LAS VEGAS FAMILY HISTORY CENTER by Luther F. Addington and Emory L. Hamilton Published by Cecil L. Durham Kingsport, Tennessee FHL TITLE # 488344 Chapters I through XV are an exact reprint of "Indian Stories of Virginia's Last Frontier" by Luther F. Addington and originally published by The Historical Society of Southwest Virginia. Chapter XVI "Indian Tragedies Against the Walker Family" is by Emory L. Hamilton. Printed in the United States of America by Kingsport Press Kingsport, Tennessee TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INDIANS CAPTURE MARY INGLES 1 II. MURDER OF JAMES BOONE, 27 OCTOBER 10, 1773 III. MASSACRE OF THE HENRY FAMILY 35 IV. THE INDIAN MISSIONARY 38 V. CAPTURE OF JANE WHITAKER AND POLLY ALLEY 42 VI. ATTACK ON THE EVANS FAMILY, 1779 48 VII. ATTACK ON THOMAS INGLES' FAMILY 54 VIII. INDIANS AND THE MOORE FAMILY 59 IX. THE HARMANS' BATTLE 77 X. A FIGHT FOR LIFE 84 XI. CHIEF BENGE CARRIES AWAY MRS. SCOTT 88 XII. THE CAPTIVITY OF JENNY WILEY 97 XIII. MRS. ANDREW DAVIDSON AND CHILDREN CAPTURED 114 XIV. DAVID MUSICK TRAGEDY 119 XV. CHIEF BENGE'S LAST RAID 123 XVI. INDIAN TRAGEDIES AGAINST THE WALKER FAMILY NOTE: The interesting story of Caty Sage, who was stolen from her parents in Grayson County, 1792, by a vengeful white man and later grew to womanhood among the Wyandotts in the West, is well told by Mrs. Bonnie Ball in her book, Red Trails and White, Haysi, Virginia. 1 I CAPTIVITY OF MARY DRAPER INGLES Of all the young women taken into captivity by the Indians from Virginia's western frontier none suffered more anguish, nor bore her hardships more heroically, nor behaved with more thoughtfulness to ward her captors than did Mary Draper Ingles. -

General Geological Information for the Tri-States of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee

General Geological Information for the Tri-States Of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee Southeastern Geological Society (SEGS) Field Trip to Pound Gap Road Cut U.S. Highway 23 Letcher County, Kentucky September 28 and 29, 2001 Guidebook Number 41 Summaries Prepared by: Bruce A. Rodgers, PG. SEGS Vice President 2001 Southeastern Geological Society (SEGS) Guidebook Number 41 September 2001 Page 1 Table of Contents Section 1 P HYSIOGRAPHIC P ROVINCES OF THE R EGION Appalachian Plateau Province Ridge and Valley Province Blue Ridge Province Other Provinces of Kentucky Other Provinces of Virginia Section 2 R EGIONAL G EOLOGIC S TRUCTURE Kentucky’s Structural Setting Section 3 M INERAL R ESOURCES OF THE R EGION Virginia’s Geological Mineral and Mineral Fuel Resources Tennessee’s Geological Mineral and Mineral Fuel Resources Kentucky’s Geological Mineral and Mineral Fuel Resources Section 4 G ENERAL I NFORMATION ON C OAL R ESOURCES OF THE R EGION Coal Wisdom Section 5 A CTIVITIES I NCIDENTAL TO C OAL M INING After the Coal is Mined - Benefaction, Quality Control, Transportation and Reclamation Section 6 G ENERAL I NFORMATION ON O IL AND NATURAL G AS R ESOURCES IN THE R EGION Oil and Natural Gas Enlightenment Section 7 E XPOSED UPPER P ALEOZOIC R OCKS OF THE R EGION Carboniferous Systems Southeastern Geological Society (SEGS) Guidebook Number 41 September 2001 Page i Section 8 R EGIONAL G ROUND W ATER R ESOURCES Hydrology of the Eastern Kentucky Coal Field Region Section 9 P INE M OUNTAIN T HRUST S HEET Geology and Historical Significance of the -

An Ethnographic Case Study of College Pathways Among Rural, First-Generation Students

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Country Roads Take Me...?: An Ethnographic Case Study of College Pathways Among Rural, First-Generation Students Author: Sarah Elizabeth Beasley Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1827 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2011 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. BOSTON COLLEGE Lynch School of Education Department of Educational Administration and Higher Education Program in Higher Education COUNTRY ROADS TAKE ME…?: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC CASE STUDY OF COLLEGE PATHWAYS AMONG RURAL, FIRST- GENERATION STUDENTS Dissertation by SARAH ELIZABETH BEASLEY submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2011 © Copyright by Sarah Elizabeth Beasley 2011 Country Roads Take Me…?: An Ethnographic Case Study of College Pathways among Rural, First-Generation Students by Sarah Elizabeth Beasley Dr. Ted Youn, Dissertation Chair ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to examine college pathways or college access and success of rural, first-generation students. Most research on college pathways for low- and moderate-income students focuses on those students as a whole or on urban low- socioeconomic status (SES) students. (Caution is in order when generalizing the experiences of low-SES urban students to those of low-SES rural students.) The literature reveals that rural students attend college at lower rates than their urban and suburban counterparts and are likely to have lower college aspirations. Why such differences exist remains highly speculative in the literature. -

Windows Into Our Past a Genealogy of the Parsons, Smith & Associated Families, Vol

WINDOWS INTO OUR PAST A Genealogy Of The Parsons, Smith & Associated Families Volume One Compiled by: Judy Parsons Smith CROSSING into and Through THE COMMONWEALTH WINDOWS INTO OUR PAST A Genealogy Of The Parsons, Smith & Associated Families Volume One Compiled by: Judy Parsons Smith Please send any additions or corrections to: Judy Parsons Smith 11502 Leiden Lane Midlothian, VA 23112-3024 (804) 744-4388 e-mail: [email protected] Lay-out Design by: D & J Productions Midlothian, Virginia © 1996, Judy P. Smith 2 Dedicated to my children, so that they may know from whence they came. 3 INTRODUCTION I began compiling information on my family in 1979, when my Great Aunt Jo first introduced me to genealogy. Little did I know where that beginning would lead. Many of my first few generation were already set out in other publications where I could easily find them. Then there were others which have taken many years even to begin to develop. There were periods of time that I consistently worked on gathering information and "filling out" all the paperwork. Then there have been periods of time that I have just allowed my genealogy to set aside for a year or so. Then I something would trigger the genealogy bug and I would end up picking up my work once again with new fervor. Through the years, I have visited with family that I didn't even know that I had. In turn my correspondence has been exhaustive at times. I so enjoy sending out and receiving family information. The mail holds so many surprises. -

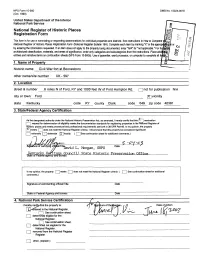

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "X" in the appn by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For fu architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place addi1 entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all it 1. Name of Property historic name Civil War fort at Boonesboro__________________________________ other name/site number CK - 597________________________________________ 2. Location street & number .6 miles N of Ford, KY and 1000 feet W of Ford Hampton Rd. Qnot for publication N/A city or town Ford [XI vicinity state Kentucky code KY county Clark code 049 zip code 40391 3. State/Federal Agency Certification \r __ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ | nomination I I request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic places and meets procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property PM meets I I does not meet the National Register criteria.