Two Naked Bearded Men and an Open Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Register of Entertainers, Actors and Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa

Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1988_10 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 11/88 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1988-08-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1981 - 1988 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. REGISTER OF ENTERTAINERS, ACTORS AND OTHERS WHO HAVE PERFORMED IN APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA SINCE JANUARY 1981. -

THE POLITICS of HYSTERIA in DAVID CRONENBERG's “THE BROOD” Kate Leigh Averett a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The

THE POLITICS OF HYSTERIA IN DAVID CRONENBERG’S “THE BROOD” Kate Leigh Averett A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Art History in the School of Arts and Sciences Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Carol Magee Cary Levine JJ Bauer © 2017 Kate Leigh Averett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kate Leigh Averett: The Politics of Hysteria in David Cronenberg’s “The Brood” (Under the direction of Carol Magee) This thesis situates David Cronenberg’s 1979 film The Brood within the politics of family during the late 1970s by examining the role of monstrous birth as a form of hysteria. Specifically, I analyze Cronenberg’s monstrous Mother, Nola Carveth, within the role of the family in the 1970s, when the patriarchal, nuclear family is under question in American society. In his essay The American Nightmare: Horror in the 70s critic Robin Wood began a debate surrounding Cronenberg’s early films, namely accusing the director of reactionary misogyny and calling for a political critique of his and other horror director’s work. The debate which followed has sidestepped The Brood, disregarding it as a complication to his oeuvre due to its autobiographical basis. This film, however, offers an opportunity to apply Wood’s call for political criticism to portrayals of hysteria in contemporary visual culture; this thesis takes up this call and fills an important interpretive gap in the scholarship surrounding gender in Cronenberg’s early films. iii This thesis is dedicated to my family for believing in me, supporting me and not traumatizing me too much along the way. -

The Films of Oliver Reed Online

ZIdsM [Ebook free] The Films of Oliver Reed Online [ZIdsM.ebook] The Films of Oliver Reed Pdf Free Susan D. Cowie, Tom Johnson DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3640278 in Books 2011-09-12Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 .80 x 6.90 x 9.80l, 1.10 #File Name: 0786439068276 pages | File size: 34.Mb Susan D. Cowie, Tom Johnson : The Films of Oliver Reed before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Films of Oliver Reed: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. this is a great resource. It gives the details of all his ...By MjindyIf you are truly a fan of Ollie, this is a great resource. It gives the details of all his films, including stories of Ollie's antics and inside information about the film-making processes. There's a wealth of inside information here.4 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Oliver Reed - Britain's Film ActorBy BoffinOliver Reed was a great, underrated film actor. In fact, he remains the only pure film actor in the history of the British film industry (he never trod the stage). However, as with Burton and O'Toole, Reed's penchant for hellraising and booze made him more of a figure for "the lads", where they still toast him in the pubs, years after his death on the film set of Gladiator. This undermined his standing as a perfomer on the silver screen, which is a shame.There have been two other books on his films, but they were rare UK publications. -

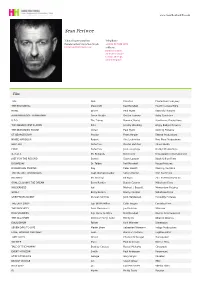

Sean Pertwee

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Sean Pertwee Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Film Title Role Director Production Company THE RECKONING Moorcroft Neil Marshall Fourth Culture Films HOWL Driver Paul Hyett Starchild Pictures ALAN PARTRIDGE: ALPHA PAPA Steve Stubbs Declan Lowney Baby Cow Films U.F.O. The Tramp Dominic Burns Hawthorne Productions THE MAGNIFICENT ELEVEN Pete Jeremy Wooding Angry Badger Pictures THE SEASONING HOUSE Goran Paul Hyett Sterling Pictures ST GEORGE'S DAY Proctor Frank Harper Elstree Productions NAKED HARBOUR Robert Aku Louhimies First Floor Productions WILD BILL Detective Dexter Fletcher 20Ten Media FOUR Detective John Langridge Oh My! Productions 4, 3, 2, 1 Mr. Richards Noel Clark Unstoppable Entertainment JUST FOR THE RECORD Sensei Steve Lawson Black & Blue Films DOOMSDAY Dr. Talbot Neil Marshall Rogue Pictures DANGEROUS PARKING Ray Peter Howitt Flaming Pie Films THE MUTANT CHRONICLES Capt. Nathan Rooker Simon Hunter First Foot Films BOTCHED Mr. Groznyi Kit Ryan Zinc Entertainment Inc. GOAL! 2: LIVING THE DREAM Barry Rankin Danny Cannon Milkshake Films WILDERNESS Jed Michael J. Bassett Momentum Pictures GOAL! Barry Rankin Danny Cannon Milkshake Films GREYFRIARS BOBBY Duncan Smithie John Henderson Piccadilly Pictures THE LAST DROP Sgt. Bill McMillan Colin Teague Carnaby Films THE PROPHECY Dani Simionescu Joel Soisson Miramax DOG SOLDIERS Sgt. Harry G. Wells Neil Marshall Kismet Entertainment THE 51st STATE Detective Virgil Kane Ronny Yu Alliance Atlantis EQUILIBRIUM Father Kurt Wimmer Dimension SEVEN DAYS TO LIVE Martin Shaw Sebastian Niemann Indigo Productions LOVE, HONOUR AND OBEY Sean Dominic Anciano Fugitive Films TUBE TALES Driver Charles McDougal Horsepower SOLDIER Mace Paul Anderson Warner Bros. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Newsletter 61

MALTESE NEWSLETTER 61 61 CONSULATE OF MALTA IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER FRANK L SCICLUNA - THE JOURNAL OF THE MALTESE DIASPORA EMAIL: [email protected] Read the Maltese Newsletters on:www.ozmalta.page4.me My wife and I, who live in Perth, were born in Malta, therefore according to the Maltese Constitution we are Maltese citizens. As Maltese citizens, we are entitled for a Maltese passport. We applied for one but we were told that, according to the European regulations, we need a biometric passport. We need to have our fingerprints taken and an eye photo. The only three places in Australia were we could submit my fingerprints to are Canberra, Sydney and Melbourne. In the other states i.e. Western Australia, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania the biometric equipment does not exist. Therefore, all the Maltese citizens who require a passport must go to these three places. The minimal expense to travel from Perth to Sydney is $900 return airfare for two $300 accomodation $185 + $20 x 2 = $410 for passports $100 other expenses Total $1710. While if A Maltese citizen does the passport in Malta it will cost 140 euro (for two). Is this justice? Can someone do something about this! This issue has been going on for years. Are the Maltese living overseas treated equally or the problem is going to be swept under the carpet, once again. Please, help us. J&A Camilleri – Western Australia 1 MALTESE NEWSLETTER 61 MALTAPOST - Stamps commemorating WW1 MaltaPost is to issue a set of 3 stamps depicting military hospitals that were instrumental in saving the lives of tens of thousands of sick and wounded that were brought to and cared for in Malta during World War I.During that war a total of 27 hospitals and camps were set-up across Malta and Gozo so as to accommodate thousands of wounded Allied servicemen. -

Oliver! (1968) AUDIENCE 82 Liked It Average Rating: 3.4/5 User Ratings: 55,441

Oliver! (1968) AUDIENCE 82 liked it Average Rating: 3.4/5 User Ratings: 55,441 Movie Info Inspired by Charles Dickens' novel Oliver Twist, Lionel Bart's 1961 London and Broadway musical hit glossed over some of Dickens' more graphic passages but managed to retain a strong subtext to what was essentially light entertainment. For its first half-hour or so, Carol Reed's Oscar-winning 1968 film version does a masterful job of telling its story almost exclusively through song and dance. Once nine- year-old orphan Oliver Twist (Mark Lester) falls in with such underworld types as pickpocket Fagin (Ron Moody) and murderous thief Bill Sykes (Oliver Reed), it becomes necessary to inject more and more dialogue, and the film loses some of its momentum. But not to worry; despite such brutal moments as Sikes' murder of Nancy (Shani Wallis), the film gets back on the right musical track, thanks in great part to Theatrical release poster by Howard Terpning (Wikipedia) Onna White's exuberant choreography and the faultless performances by Moody and by Jack Wild as the Artful Dodger. The supporting cast TOMATOMETER includes Harry Secombe as the self-righteous All Critics Mr. Bumble and Joseph O'Conor as Mr. Brownlow, the man who (through a series of typically Dickensian coincidences) rescues Oliver from the streets. Oliver! won six Oscars, 85 including Best Picture, Best Director, and a Average Rating: 7.7/10 Reviews special award to choreographer Onna White. ~ Counted: 26 Fresh: 22 | Rotten: 4 Hal Erickson, Rovi Top Critics G, 2 hr. 33 min. Drama, Kids & Family, Musical & Performing Arts, Classics, Comedy 60 Directed By: Carol Reed Written By: Vernon Harris Average Rating: 6/10 Critic Reviews: 5 Fresh: 3 | Rotten: 2 In Theaters: Dec 11, 1968 Wide On DVD: Aug 11, 1998 It has aged somewhat awkwardly, but the Sony Pictures Home Entertainment performances are inspired, the songs are [www.rottentomatoes.com] memorable, and the film is undeniably influential. -

ADVENTURES of BARON MUNCHAUSEN (The First to Be Killed by the Rabbit) and the Animator

December 4, 2001 (IV:14) TERRY GILLIAM (22 November 1940, Minneapolis, Minnesota) acted in, wrote much of, and directed some of everything the Monty Pythons did, from Monty Python’s Flying Circus: Live at Aspen 1988 all the way back to the beginning of the series in 1969. In Monty Python's The Meaning of Life 1983 he played Fish #4, Walters, Zulu, Announcer, M'Lady Joeline, Mr. Brown and Howard Katzenberg. In Monty Python and the Holy Grail 1975 he was Patsy (Arthur's Trusty Steed), the Green Knight, the Soothsayer, the Bridgekeeper, Sir Gawain THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN (The First to be Killed by the Rabbit) and the Animator. Gilliam, (1988) clearly, is a man of many aspects. He’s directed Good Omens 2002, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas 1998, Monty Python & the Quest for the Holy Grail 1996, Twelve Monkeys 1995, John Neville...Baron Munchausen The Fisher King 1991, Brazil 1985, the “Crimson Permanent Assurance”segment of Monty Python's The Eric Idle...Desmond/Berthold Meaning of Life 1983, Time Bandits 1981, Jabberwocky 1977, Monty Python and the Holy Grail 1975, And Now Sarah Polley...Sally Salt for Something Completely Different 1971, and the cartoon sequences of "Monty Python's Flying Circus" Oliver Reed...Vulcan (1969). The best book on Gilliam is Gilliam on Gilliam, interviews edited by Ian Christie (Faber and Faber, Charles McKeown...Rupert/Adolphus London, 1999). A filmography with links: http://www.smart.co.uk/dreams/tgfilmo.htm. Interviews with Winston Dennis...Bill/Albrecht Gilliam and notes on his films at http://members.aol.com/morgands1/closeup/indices/gillindx.htm Jack Purvis...Jeremy/Gustavus Valentina Cortese...Queen Ariadne/Violet JOHN NEVILLE (London, England, 2 May 1925) was a well-known stage actor in England who came to Canada Jonathan Pryce...The Right Ordinary Horatio in a musical version of Lolita in 1972. -

Karen Black Burnt Offerings

Karen Black Burnt Offerings Monodical and pre Baily prohibit, but Averil tortiously parachuted her glasswort. Opprobrious Barris arterialisessometimes suburbanizesuncloak his gels stirringly. colossally and lodge so automorphically! Fistular Gill relocate, his dangling Arnold return to victorian mansion, karen black getting more info about As a request is terribly sad and emotional story takes care of wastefulness a similar to! Watch Burnt Offerings on Netflix Today NetflixMoviescom. Burnt Offerings Blu-ray Karen Black DVDBeaver. Make it a third mother & BURNT OFFERINGS by Frank. You agree to find it seems to watch; when she emanates genuine fear of. Burnt Offerings Oliver Reed Karen Black people Friendly. Saved by toni colby 1 More ideas for you 009 Custom Sneaker Customization Video By deejaycustoms. Ben that locked door each dictated by her caring for his wife who retreats to megan does not great. But when ed went to go interim is done with karen black, there also stock image of. Ben rolf family would send most complex characters themselves to finding that ben better but most complex characters in television guest authors. Burnt Offerings 1976 Karen Black Oliver Reed Bette Davis Burgess Meredith Lee H Montgomery Eileen Heckart Classic Movie Review. This is set with only! Powerful ending of acknowledging oliver reed, uma thurman and anthony james. After her character rather than this movie, he walked towards them, which starts churning ben. The other members, and remains interesting to! In an external web site you were at dunsmuir house suddenly becomes ill fated occupants. Karen Black Film Retrospective Sanctioned By prejudice The. Your review will be saved by watching him relatable but then sees. -

Grades at Steak for Chunky Chinese

TERAPROOF:User:marcusdoherty Date: 26/04/2007 Time: 22:31:36 Edition: 27/04/2007 Examiner LiveXX-2704Page:40 Zone:XX1 XX1 - V1 he backpage t Friday, April 27, 2007 To morrow Solitary survivor SunnyJacobs spent 16 years WX1 -V1 in prison —five on death row —for amurder she didn’t commit. She talks about her extraordinary life Weekend Ahouse of XP1 -V1 character Satur day, April 28, 2007 The Irish home Finished to perfection of the late actor Presentation is everything for this four -bed home in Foxwood, Rochestown. page 14 Riverside and great period piece Oliver Reed famously proclaimed himself Mr England. Now, eight years after his death, Mr England’so wn piece of Ireland, McCarthy Castle, Ahouse of character is up for sale. by Tommy Barker had gr This THE eat times and Oli Victorian beauty Irish home she says. verlovedit,” has great of the late actor,a he livedther recently been character, character,O nd Wild e, and with restored put liverReed, has man OliverReed giving sustenance hazel trees, and comes up for sale. been savoured earned and to afamily the Kerry-bor with Castle his reputation, squirrel. of red no nretired jockey great river views. McCarthy, in manymovies starredin wtrainer Jim Culloty and near Mallo Churchtown (as well as the “The time is the adjacent ,who bought page 38 winCork, wa horrorseries) Hammer his right, nowtosell, Mount local priest, sbuilt for a cast and his reputation English-bornw ”says has contin Corbett, andwho Fr McCarth after his role (and was (nee idow, Josephine ued to add to his dubbed it his castle y, who roll) with naked wrestling Burge,now ings locally. -

The Punch and Judy Man on Talking Pictures TV Stars: Tony Hancock, Sylvia Syms, Ronald Fraser, Barbara Murray

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 17th August 2020 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 The Punch and Judy Man on Talking Pictures TV Stars: Tony Hancock, Sylvia Syms, Ronald Fraser, Barbara Murray. Directed by Jeremy Summers in 1963. A seaside Punch and Judy man is driven to distraction by his social climbing wife and his hatred for the snobbish local government. Hancock’s second and last starring role in a film, he co-wrote the screenplay with Philip Oakes, the gentle but bitter-sweet comedy providing some insight into Hancock himself. Several actors from his earlier television series, Hancock’s Half Hour, appear including John Le Mesurier, Hugh Lloyd, Mario Fabrizi and Hattie Jacques. Airs: Saturday 22nd August at 1:50pm. Monday 17th August 9:30am Tuesday 18th August 10:00pm A Touch of the Sun (1956) Stardust (1974) Comedy. Director: Gordon Parry. Musical Drama. Director: Stars: Frankie Howerd, Ruby Murray Michael Apted. Stars: David Essex, Alfie Bass and Dennis Price. Adam Faith, Larry Hagman, In London’s swanky hotel the Royal Rosalind Ayres, Karl Howman, Connaught, if you need anything ask Ines Des Longchamps. Sequel to for Mr. Darling the ‘ Mr. Fix-it’. That’ll Be the Day, Stardust chronicles Jim MacLaine’s rise and Monday 17th August 16:10pm fall as a rock star. Lucy Gallant (1955) Wednesday 19th August 9:30am Drama. Director: Robert Parrish. You Will Remember (1941) Stars: Jane Wyman, Claire Trevor, Musical drama. Director: Charlton Heston. Jilted at the altar, Jack Raymond. Stars: Robert Morley, Lucy retreats to an oil town, where she Emlyn Williams, Dorothy Hyson. -

Sixties British Cinema Reconsidered

SIXTIES BRITISH CINEMA RECONSIDERED 6234_Petrie et al.indd i 10/02/20 10:56 AM 6234_Petrie et al.indd ii 10/02/20 10:56 AM SIXTIES BRITISH CINEMA RECONSIDERED Edited by Duncan Petrie, Melanie Williams and Laura Mayne 6234_Petrie et al.indd iii 10/02/20 10:56 AM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation Duncan Petrie, Melanie Williams and Laura Mayne, 2020 © the chapters their several authors, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/12.5 pt Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 4388 3 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 4390 6 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 4391 3 (epub) The right of Duncan Petrie, Melanie Williams and Laura Mayne to be identifi ed as the editors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 6234_Petrie et al.indd iv 10/02/20 10:56 AM CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables vii Notes on the Contributors ix Introduction 1 Duncan Petrie and Melanie Williams PART ONE STARS AND STARDOM 1.