The Development of the Overseas Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repurposing the East Coast Railway: Florida Keys Extension a Design Study in Sustainable Practices a Terminal Thesis Project by Jacqueline Bayliss

REPURPOSING THE EAST COAST RAILWAY: FLORIDA KEYS EXTENSION A DESIGN STUDY IN SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES A terminal thesis project by Jacqueline Bayliss College of Design Construction and Planning University of Florida Spring 2016 University of Florida Spring 2016 Terminal Thesis Project College of Design Construction & Planning Department of Landscape Architecture A special thanks to Marie Portela Joan Portela Michael Volk Robert Holmes Jen Day Shaw Kay Williams REPURPOSING THE EAST COAST RAILWAY: FLORIDA KEYS EXTENSION A DESIGN STUDY IN SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES A terminal thesis project by Jacqueline Bayliss College of Design Construction and Planning University of Florida Spring 2016 Table of Contents Project Abstract ................................. 6 Introduction ........................................ 7 Problem Statement ............................. 9 History of the East Coast Railway ...... 10 Research Methods .............................. 12 Site Selection ............................... 14 Site Inventory ............................... 16 Site Analysis.................................. 19 Case Study Projects ..................... 26 Limitations ................................... 28 Design Goals and Objectives .................... 29 Design Proposal ............................ 30 Design Conclusions ...................... 40 Appendices ......................................... 43 Works Cited ........................................ 48 Figure 1. The decommissioned East Coast Railroad, shown on the left, runs alongside the Overseas -

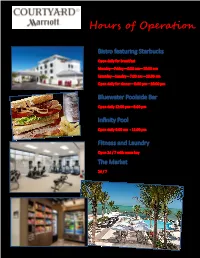

Hours of Operation

Hours of Operation Bistro featuring Starbucks Open daily for breakfast Monday—Friday—6:30 am—10:30 am Saturday—Sunday—7:00 am—10:30 am Open daily for dinner—5:00 pm—10:00 pm Bluewater Poolside Bar Open daily 12:00 pm—8:00 pm Infinity Pool Open daily 6:00 am - 11:00 pm Fitness and Laundry Open 24 / 7 with room key The Market 24 / 7 Airports Marathon Jet Center About 5 minutes away 3.5 Miles Www.marathonjetcenter.com Getting Marathon General Aviation About 6 minutes away Around in the 6 Miles Www.marathonga.com Florida Keys Miami International Airport About 2 hours and 15 minutes away 115 Miles Www.miami-airport.com Fort Lauderdale Airport About 2 hours and 45 minutes away 140 Miles Www.fortlauderdaleinternationalairport.com ******************** Complimentary Shuttle Service Contact the front desk for assistance Taxi and Shuttle Dave’s Island Taxi—305.289.8656 Keys Shuttle—305.289.9997 ******************** Car Rental Enterprise — 305.289.7630 Avis — 305.743.5428 Budget — 305.743.3998 ********************* Marathon Chamber of Commerce 12222 Overseas Highway, Marathon, Florida 33050 305-743-5417 Don’t Miss It in the Florida Keys Key Largo Marathon John Pennekamp State Park Turtle Hospital 102601 Overseas Highway 2396 Overseas Highway 305. 451. 6300 305. 743. 2552 African Queen and Glass Boat Dolphin Research Center U.S. 1 and Mile Marker 100 58901 Overseas Highway 305. 451. 4655 305. 289. 1121 Florida Keys Aquarium Encounters Islamorada 11710 Overseas Highway 305. 407. 3262 Theatre of the Sea 84721 Oversea Highway Sombrero Beach 305.664.2431 Mile Marker 50 305. -

A Good Foundation

A Good Foundation All Aboard: History, Culture, and Innovation on the Florida East Coast Railway Curriculum Connections: Grade Level: Math, Art, Science, Social Studies, Florida History th 4 Grade Objectives: Materials: Students will be introduced to the Florida East Coast Railway and engineering Book: methods for building a bridge foundation under water. They will construct a • Bridges! Amazing Structures cofferdam. to Design, Build and Test by Carol A. Johmann and Standards: Elizabeth J. Rieth Photos: MAFS.4.MD: Measurement and Data • Henry M. Flagler SS.4.G.1: Geography – The World in Spatial Terms • Trains on the Florida East SC.4.P: Physical Science Coast Railway Map of: Corresponding Map Hot Spot: • FEC Railway Showing Extension to Key West Jewfish Creek, FL • FEC Railway Extension to Key West Lesson Procedure Additional Supplies: • Two Medium Sized Bowls Introduction: • Popsicle Sticks • Masking Tape Introduce the theme of the lesson, the bridges of the Overseas Railway. Show • Sand or Dirt the students the pictures of the railroad and the map. • Plastic Wrap • Water Discuss how Henry Flagler was determined to build a railroad connecting the • Turkey Baster or Eye Keys all the way to Key West. Ask the students what they think life may have Droppers been like before the bridges. 1 | All Aboard: History, Culture, and Innovation on the Florida East Coast Railway Discuss the benefits to building a railroad connecting the Florida Keys to mainland Florida (a new way for people to travel, a new way for supplies to get in, etc.) and ask the students what the challenges to building something like this would have been (nothing like this had ever been done before, when the Key West Extension opened it was called the 8th Wonder of the World). -

Bridge Jump May Be Hoax by DAVID GOODHUE Al Battery

WWW.KEYSINFONET.COM WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 1, 2014 VOLUME 61, NO. 1 G 25 CENTS NORTH KEY LARGO Bridge jump may be hoax By DAVID GOODHUE al battery. Dziadura sought for questioning in a.m. Monday saying he was Monroe County deputies [email protected] “At this point in time, my going to tie a 40-pound found Dziadura’s Honda personal impression is it is sex case; no body found after search dumbbell weight to his leg minivan. Inside, the deputies Monroe County Sheriff staged,” Ramsay told US1 and jump from the 65-foot found a 40-pound dumbbell, Rick Ramsay suspects a Radio’s Bill Becker on the came soon after Miami-Dade facts, I have to also consider span. Both Monroe deputies two baseball bats, a crowbar, Miami-Dade man who may “Morning Magazine” radio detectives wanted to question the subject staged his suicide and Miami-Dade police a black suitcase, shoes, or may not have jumped off show Tuesday. him in a sexual battery case, to elude Miami-Dade detec- arrived at the bridge after the clothes and a child car safety the Card Sound Bridge in Although Miami-Dade Monroe County Sheriff’s tives who are seeking him for relative called police. seat in the backseat. The keys North Key Largo early County Police say there is no Office Detective Deborah questioning in a sexual bat- The two Miami-Dade were in the ignition. Monday morning may have arrest warrant for 38-year-old Ryan wrote in her report. tery case,” Ryan wrote. officers found Dziadura’s A view of Dziadura’s staged an elaborate hoax to James Alan Dziadura, his “Additionally, should no Dziadura sent a text mes- iPhone at the top of the elude charges of capital sexu- supposed suicide attempt body be found, based on the sage to a relative around 1 bridge on a railing. -

Ocean Reef Community Association (ORCA) North Key Largo, FL

Welcome to Ocean Reef Community Association (ORCA) North Key Largo, FL Director of Administration for Public Safety Position Open - Apply by April 18, 2016 The Ocean Reef Community Association (ORCA) is seeking a talented, proactive, polished and articulate individual to join its management team as the Director of Administration for Public Safety. Unlike many community associations, ORCA has its own public safety function (Security, Fire, EMS) and works extremely closely with the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office. The function involves more than just traditional policing. It is all about ensuring that the Ocean Reef Community is safe, secure and well- protected, as well as providing white glove public safety services to the Community! If you are a very skilled administrator with a strong knowledge of public safety and are interested in a very demanding job and environment, please read on. BACKGROUND Nestled among 2,500 acres of secluded and lush tropics, Ocean Reef is located on the northernmost tip of Key Largo in the Florida Keys. It is a very high-end, world class community. It is a debt- free, member-owned private community and not a place to retire – it’s a place of renewal with nature, loved ones and friends. It is Director of Administration for Public Safety | North Key Largo, Florida a place where generations of members gather to celebrate a Unique Way of Life. No detail has been overlooked in the planning of the Ocean Reef Community and family members of all ages enjoy first-class facilities. Many members have decided that year-round living at “The Reef” is a perfect choice. -

Executive Summary

Coco Palms 21585 Old State Road 4A Cudjoe Key, Florida TRAFFIC STUDY prepared for: Smith Hawks KBP CONSULTING, INC. January 2018 Revised July 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTORY ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Existing Land Use and Access ......................................................................................................... 3 Proposed Land Use and Access ........................................................................................................ 3 EXISTING CONDITIONS ........................................................................................................................... 4 Existing Roadway Network .............................................................................................................. 4 Existing Traffic Conditions .............................................................................................................. 4 TRIP GENERATION ................................................................................................................................... 5 TRIP DISTRIBUTION ................................................................................................................................. 6 TRAFFIC IMPACT ANALYSES ............................................................................................................... -

Appendix C - Monroe County

2016 Supplemental Summary Statewide Regional Evacuation Study APPENDIX C - MONROE COUNTY This document contains summaries (updated in 2016) of the following chapters of the 2010 Volume 1-11 Technical Data Report: Chapter 1: Regional Demographics Chapter 2: Regional Hazards Analysis Chapter 4: Regional Vulnerability and Population Analysis Funding provided by the Florida Work completed by the Division of Emergency Management South Florida Regional Council STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY This page intentionally left blank. STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY Page A. Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 B. Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 C. Demographic Trends ...................................................................................... 4 D. Census Maps .................................................................................................. 9 E. Hazard Maps .................................................................................................15 F. Critical Facilities Vulnerability Analysis .............................................................23 List of Tables Table 1 Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 Table 2 Health Care Facilities Vulnerability -

Let It Take You Places

states. Refer to map. to Refer states. GB 04 | 2021 | 04 GB Interoperable with other other with Interoperable el código QR. código el en español, escanee escanee español, en Para leer este folleto folleto este leer Para apps for iOS or Android. or iOS for apps account online or with FREE FREE with or online account SunPass.com Access and manage your your manage and Access program. Department of Transportation. of Department Check with rental agent about their toll toll their about agent rental with Check • SunPass® is a registered trademark of the Florida Florida the of trademark registered a is SunPass® at toll booths. toll at transponder upon returning the vehicle. the returning upon transponder Saturdays 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. 5 to a.m. 8:30 Saturdays You don’t have to wait in line line in wait to have don’t You Remember to remove your SunPass SunPass your remove to Remember • Monday–Friday, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and and p.m. 7 to a.m. 7 Monday–Friday, Call 1-888-TOLL-FLA (1-888-865-5352), (1-888-865-5352), 1-888-TOLL-FLA Call • (1-888-865-5352). 1-888-TOLL-FLA call or app, Android or Rock Stadium in Miami. in Stadium Rock Visit SunPass.com Visit • during rental period via SunPass.com, iOS iOS SunPass.com, via period rental during and Tampa, as well as Hard Hard as well as Tampa, and Download the free iOS or Android app app Android or iOS free the Download • Add vehicle to your SunPass account account SunPass your to vehicle Add • Miami, Orlando, Palm Beach Beach Palm Orlando, Miami, following ways: ways: following Lauderdale-Hollywood, Lauderdale-Hollywood, with you. -

NCEF a Connector of Resources Within Collier County During COVID-19

A8 NEWS WEEK OF MAY 7-13, 2020 www.FloridaWeekly.com NAPLES FLORIDA WEEKLY Owner of cinema group building at Coastland Center files for bankruptcy FLORIDA WEEKLY Certain news outlets including the Wall Street Journal reported this week that the owner of CMX Cinemas has filed for bankruptcy protection. As pre- viously reported in Florida Weekly, a state-of-the-art CMX Cinébistro movie theater is currently being built on the footprint of the former Sears store at Coastland Center mall in Naples. According to an April 27 article about the bankruptcy filing from The Real Deal, which reports on real estate news, Miami-based Cinemex Holdings USA filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in Miami. The company is owned by Mexico-based Grupo Cinemex SA de CV, which controls CMX Cinemas with 41 locations in the Midwest, Northeast and the South, Real Deal reported. CMX Cinemas had planned to open new locations at Wrigleyville in Chi- cago; American Dream Mall in East Rutherford, New Jersey; and Coastland Center in Naples this year, according to its website. The Wall Street Journal reported that the owner of CMX Cinemas filed for bankruptcy protection saying it needs breathing room from movie studios and landlords because of the economic cri- ERIC STRACHAN / FLORIDA WEEKLY sis triggered by the coronavirus pan- Workmen were on the jobsite Tuesday where the CMX Cinébistro movie theater is under construction at Coastland Center mall. demic. In a statement, CMX Cin- thet country, the Miami Herald As reported by Real Deal’s Keith er, Scotia Bank, HSBC Mexico, and SAB- emas said it had experienced a reported. -

BAHIA HONDA STATE PARK Bahia Honda Key Is Home to One of Florida’S 36850 Overseas Highway Southernmost State Parks

HISTORY BAHIA HONDA STATE PARK Bahia Honda Key is home to one of Florida’s 36850 Overseas Highway southernmost state parks. The channel Big Pine Key, FL 33043 between the old and new Bahia Honda bridges 305-872-2353 is one of the deepest natural channels in the Florida Keys. The subtropical climate has created a natural environment found nowhere else in the continental U.S. Many plants and PARK GUIDELINES animals in the park are rare and unusual, Please remember these tips and guidelines, and including marine plant and animal species of enjoy your visit: Caribbean origin. • Hours are 8 a.m. until sunset, 365 days a year. BAHIA HONDA The park has one of the largest remaining • An entrance fee is required. stands of the threatened silver palms. • The collection, destruction or disturbance of STATE PARK Specimens of the silver palm and the yellow plants, animals or park property is prohibited. satinwood, found in the park, have been • Pets are permitted in designated areas only. certified as national champion trees. The rare, Pets must be kept on a leash no longer than small-flowered lily thorn may also be found in six feet and well-behaved at all times. the park. • Fishing, boating, swimming and fires are The geological formation of Bahia Honda is Key allowed in designated areas only. A Florida Largo limestone. It is derived from a pre-historic fishing license may be required. Use diver- coral reef similar to the present-day living reefs down flags. off the Keys. Because of a drop-in sea level • Fireworks and hunting are prohibited. -

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COLA

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1: HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION TABLE OF CONTENTS 2.4 HYDROLOGIC ENGINEERING ..................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1 HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION ............................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.1 Site and Facilities .....................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.2 Hydrosphere .............................................................................2.4.1-3 2.4.1.3 References .............................................................................2.4.1-12 2.4.1-i Revision 6 Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1 LIST OF TABLES Number Title 2.4.1-201 East Miami-Dade County Drainage Subbasin Areas and Outfall Structures 2.4.1-202 Summary of Data Records for Gage Stations at S-197, S-20, S-21A, and S-21 Flow Control Structures 2.4.1-203 Monthly Mean Flows at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 2.4.1-204 Monthly Mean Water Level at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 (Headwater) 2.4.1-205 Monthly Mean Flows in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 2.4.1-206 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 (Headwaters) 2.4.1-207 Monthly Mean Flows in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A 2.4.1-208 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A (Headwaters) 2.4.1-209 Monthly Mean Flows in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-210 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-211 NOAA -

• the Seven Mile Bridge (Knight Key Bridge HAER FL-2 Moser Channel

The Seven Mile Bridge (Knight Key Bridge HAER FL-2 Moser Channel Bridge Pacet Channel Viaduct) Linking Several Florida Keys Monroe County }-|/ -i c,.^ • Florida '■ L. f'H PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington D.C. 20240 • THE SEVEN MILE BRIDGE FL-2 MA e^ Ft. A HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD THE SEVEN MILE BRIDGE (Knight Key Bridge-Pigeon Key Bridge-Moser Channel Bridge- Pacet Channel Viaduct) Location: Spanning several Florida Keys and many miles of water this bridge is approximately 110 miles from Miami. It begins at Knight Key at the northeast end and terminates at Pacet Key at the southwest end. UTM 487,364E 476.848E 2,732,303N 2,729,606N # Date of Construction 1909-1912 as a railway bridge. Adapted as a concrete vehicular bridge on U.S. I in 1937-1938. Present Owner: Florida Department of Transpor- tation Hayden Burns Building Tallahassee, Florida 32304 Present Use: Since its conversion as a bridge for vehicles it has been in con- tinually heavy use as U.S. I linking Miami with Key West. There is one through draw span riAcis. rLi— z. \r. z.) at Moser Channel, the connecting channel between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. It is presently scheduled to be replaced by the State with con- struction already underway in 1980. Significance At the time the Florida East Coast Railway constructed this bridge it was acclaimed as the longest bridge in the world, an engineering marvel. It we.s the most costly of all Flagler's bridges in the Key West Exten- sion.